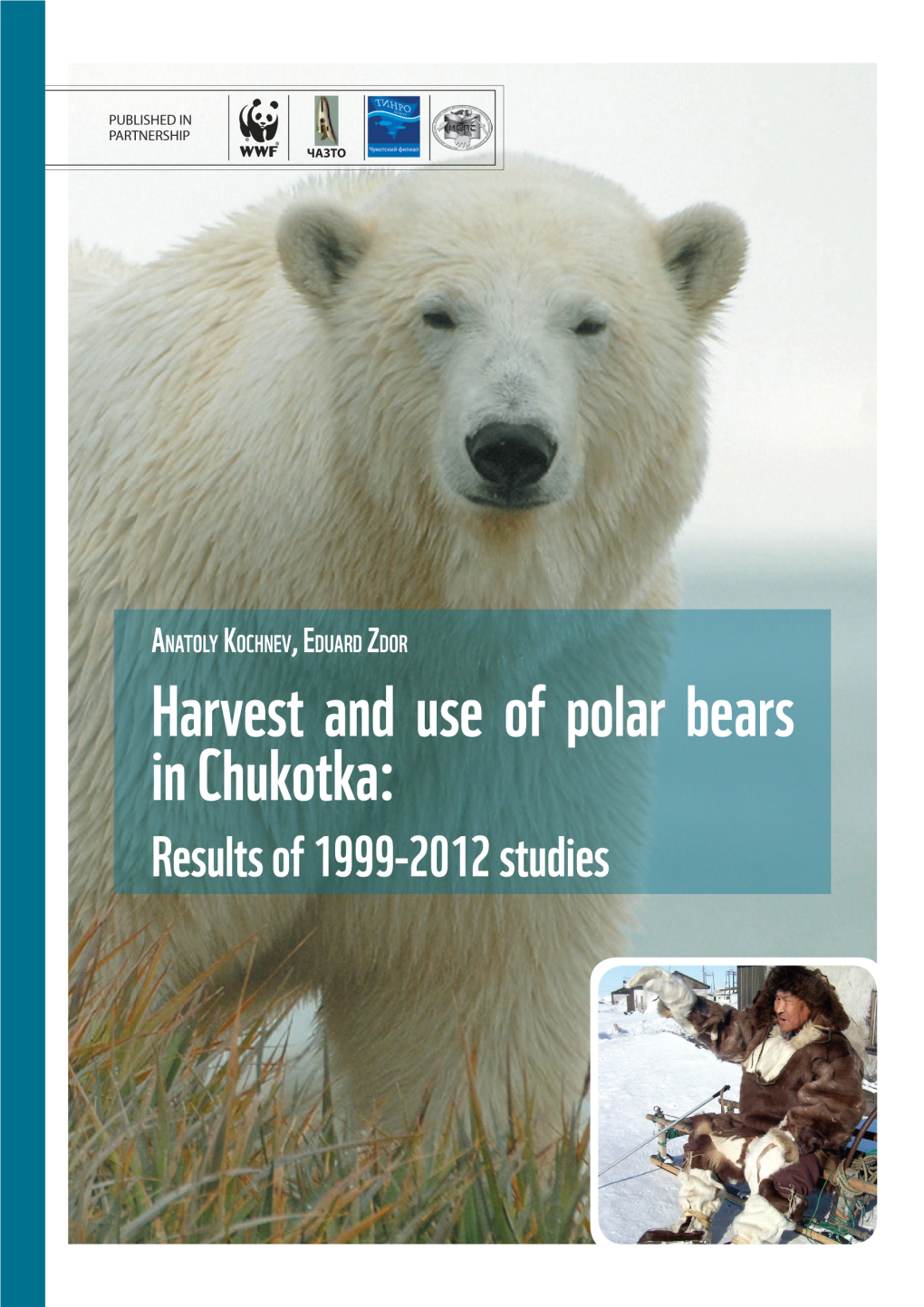

Harvest and Use of Polar Bears in Chukotka Download: 19 Mb | *.PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Post-Soviet Period Changes in Resource Utilization and Their

Post-Soviet Period Changes in Resource Utilization Title and Their Impact on Population Dynamics: Chukotka Autonomous Okrug Author(s) Litvinenko, Tamara Vitalyevna; Kumo, Kazuhiro Citation Issue Date 2017-08 Type Technical Report Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/10086/28761 Right Hitotsubashi University Repository Center for Economic Institutions Working Paper Series No. 2017-3 “Post-Soviet Period Changes in Resource Utilization and Their Impact on Population Dynamics: Chukotka Autonomous Okrug” Tamara Vitalyevna Litvinenko and Kazuhiro Kumo August 2017 Center for Economic Institutions Working Paper Series Institute of Economic Research Hitotsubashi University 2-1 Naka, Kunitachi, Tokyo, 186-8603 JAPAN http://cei.ier.hit-u.ac.jp/English/index.html Tel:+81-42-580-8405/Fax:+81-42-580-8333 Post-Soviet Period Changes in Resource Utilization and Their Impact on Population Dynamics: Chukotka Autonomous Okrug Tamara Vitalyevna Litvinenko Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences Kazuhiro Kumo Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Japan Abstract This study examines changes that have occurred in the resource utilization sector and the impact of these changes on population dynamics in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug during the post-Soviet period. This paper sheds light on the sorts of population-dynamics-related differences that have emerged in the region and how these differences relate to the use of natural resources and the ethnic composition of the population. Through this study, it was shown that changes have tended to be small in local areas where indigenous peoples who have engaged in traditional natural resource use for a large proportion of the population, while changes have been relatively large in areas where the proportion of non-indigenous people is high and the mining industry has developed. -

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure- Present State And

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present State and Future Potential By Claes Lykke Ragner FNI Report 13/2000 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Tittel/Title Sider/Pages Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present 124 State and Future Potential Publikasjonstype/Publication Type Nummer/Number FNI Report 13/2000 Forfatter(e)/Author(s) ISBN Claes Lykke Ragner 82-7613-400-9 Program/Programme ISSN 0801-2431 Prosjekt/Project Sammendrag/Abstract The report assesses the Northern Sea Route’s commercial potential and economic importance, both as a transit route between Europe and Asia, and as an export route for oil, gas and other natural resources in the Russian Arctic. First, it conducts a survey of past and present Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo flows. Then follow discussions of the route’s commercial potential as a transit route, as well as of its economic importance and relevance for each of the Russian Arctic regions. These discussions are summarized by estimates of what types and volumes of NSR cargoes that can realistically be expected in the period 2000-2015. This is then followed by a survey of the status quo of the NSR infrastructure (above all the ice-breakers, ice-class cargo vessels and ports), with estimates of its future capacity. Based on the estimated future NSR cargo potential, future NSR infrastructure requirements are calculated and compared with the estimated capacity in order to identify the main, future infrastructure bottlenecks for NSR operations. The information presented in the report is mainly compiled from data and research results that were published through the International Northern Sea Route Programme (INSROP) 1993-99, but considerable updates have been made using recent information, statistics and analyses from various sources. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Summary Audit Report 2017

SUMMARY AUDIT REPORT for the August 2016 International Cyanide Management Code Recertification Audit Prepared for: Chukotka Mining and Geological Company Kinross Gold Corporation/ Kupol Project Submitted to: International Cyanide Management Institute 1400 I Street, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20005, USA FINAL 26 April 2017 Ramboll Environ 605 1st Avenue, Suite 300 Seattle, Washington 98104 www.ramboll.com SUMMARY AUDIT REPORT Name of Mine: Kupol Mine Name of Mine Owner: Kinross Gold Corporation Name of Mine Operator: CJSC Chukotka Mining and Geological Company Name of Responsible Manager: Dave Neuburger, General Manager Address: CJSC Chukotka Mining and Geological Company Legal Address: Rultyegina Street, 2B Anadyr, Chukotka Autonomous Region Russia, 689000 Postal Address: 23 Parkovaya Street Magadan, Russia, 685000 Telephone: +7 (4132) 22-15-04 Fax: +7 (4132) 64-37-37 E-mail: [email protected] Location details and description of operation: The Kupol Mine is located in a remote north-central area of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug (AO), Russian Federation. Majority ownership of the mine was acquired by Kinross Gold Corporation (Kinross) in 2008, and has been 100% owned since 2011. The mine is operated by a wholly-owned subsidiary, CJSC Chukotka Mining and Geological Company (CMGC). The Kupol deposit is presently mined using underground methods. Another underground operation has been developed at Dvoinoye, a site 100 km due north of Kupol. No separate milling or leaching operations are presently undertaken at Dvoinoye, and ore from this operation is being processed in the Kupol mill. In 2015, combined gold production from both mines was 758 563 ounces. The Kupol and Dvoinoye mine locations are shown in Figure 1. -

Contemporary State of Glaciers in Chukotka and Kolyma Highlands ISSN 2080-7686

Bulletin of Geography. Physical Geography Series, No. 19 (2020): 5–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/bgeo-2020-0006 Contemporary state of glaciers in Chukotka and Kolyma highlands ISSN 2080-7686 Maria Ananicheva* 1,a, Yury Kononov 1,b, Egor Belozerov2 1 Russian Academy of Science, Institute of Geography, Moscow, Russia 2 Lomonosov State University, Faculty of Geography, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Russian Academy of Science, Institute of Geography, Moscow, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] a https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6377-1852, b https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3117-5554 Abstract. The purpose of this work is to assess the main parameters of the Chukotka and Kolyma glaciers (small forms of glaciation, SFG): their size and volume, and changes therein over time. The point as to whether these SFG can be considered glaciers or are in transition into, for example, rock glaciers is also presented. SFG areas were defined from the early 1980s (data from the catalogue of the glaciers compiled by R.V. Sedov) to 2005, and up to 2017: these data were retrieved from sat- Key words: ellite images. The maximum of the SGF reduction occurred in the Chantalsky Range, Iskaten Range, Chukotka Peninsula, and in the northern part of Chukotka Peninsula. The smallest retreat by this time relates to the gla- Kolyma Highlands, ciers of the southern part of the peninsula. Glacier volumes are determined by the formula of S.A. satellite image, Nikitin for corrie glaciers, based on in-situ volume measurements, and by our own method: the av- climate change, erage glacier thickness is calculated from isogypsum patterns, constructed using DEMs of individu- glacier reduction, al glaciers based on images taken from a drone during field work, and using ArcticDEM for others. -

Arctic Research of the United States, Volume 15

This document has been archived. About The journal Arctic Research of the United refereed for scientific content or merit since the States is for people and organizations interested journal is not intended as a means of reporting the in learning about U.S. Government-financed scientific research. Articles are generally invited Arctic research activities. It is published semi- and are reviewed by agency staffs and others as Journal annually (spring and fall) by the National Science appropriate. Foundation on behalf of the Interagency Arctic As indicated in the U.S. Arctic Research Plan, Research Policy Committee (IARPC) and the research is defined differently by different agencies. Arctic Research Commission (ARC). Both the It may include basic and applied research, moni- Interagency Committee and the Commission were toring efforts, and other information-gathering authorized under the Arctic Research and Policy activities. The definition of Arctic according to Act (ARPA) of 1984 (PL 98-373) and established the ARPA is “all United States and foreign terri- by Executive Order 12501 (January 28, 1985). tory north of the Arctic Circle and all United Publication of the journal has been approved by States territory north and west of the boundary the Office of Management and Budget. formed by the Porcupine, Yukon, and Kuskokwim Arctic Research contains Rivers; all contiguous seas, including the Arctic • Reports on current and planned U.S. Govern- Ocean and the Beaufort, Bering, and Chukchi ment-sponsored research in the Arctic; Seas; and the Aleutian chain.” Areas outside of • Reports of ARC and IARPC meetings; and the boundary are discussed in the journal when • Summaries of other current and planned considered relevant to the broader scope of Arctic Arctic research, including that of the State of research. -

Spanning the Bering Strait

National Park service shared beringian heritage Program U.s. Department of the interior Spanning the Bering Strait 20 years of collaborative research s U b s i s t e N c e h UN t e r i N c h UK o t K a , r U s s i a i N t r o DU c t i o N cean Arctic O N O R T H E L A Chu a e S T kchi Se n R A LASKA a SIBERIA er U C h v u B R i k R S otk S a e i a P v I A en r e m in i n USA r y s M l u l g o a a S K S ew la c ard Peninsu r k t e e r Riv n a n z uko i i Y e t R i v e r ering Sea la B u s n i CANADA n e P la u a ns k ni t Pe a ka N h las c A lf of Alaska m u a G K W E 0 250 500 Pacific Ocean miles S USA The Shared Beringian Heritage Program has been fortunate enough to have had a sustained source of funds to support 3 community based projects and research since its creation in 1991. Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev expanded their cooperation in the field of environmental protection and the study of global change to create the Shared Beringian Heritage Program. -

Arctic Marine Aviation Transportation

SARA FRENCh, WAlTER AND DuNCAN GORDON FOundation Response CapacityandSustainableDevelopment Arctic Transportation Infrastructure: Transportation Arctic 3-6 December 2012 | Reykjavik, Iceland 3-6 December2012|Reykjavik, Prepared for the Sustainable Development Working Group Prepared fortheSustainableDevelopment Working By InstituteoftheNorth,Anchorage, Alaska,USA PROCEEDINGS: 20 Decem B er 2012 ICElANDIC coast GuARD INSTITuTE OF ThE NORTh INSTITuTE OF ThE NORTh SARA FRENCh, WAlTER AND DuNCAN GORDON FOundation Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments ......................................................................... 6 Abbreviations and Acronyms .......................................................... 7 Executive Summary ....................................................................... 8 Chapters—Workshop Proceedings................................................. 10 1. Current infrastructure and response 2. Current and future activity 3. Infrastructure and investment 4. Infrastructure and sustainable development 5. Conclusions: What’s next? Appendices ................................................................................ 21 A. Arctic vignettes—innovative best practices B. Case studies—showcasing Arctic infrastructure C. Workshop materials 1) Workshop agenda 2) Workshop participants 3) Project-related terminology 4) List of data points and definitions 5) List of Arctic marine and aviation infrastructure AlASkA DepartmENT OF ENvIRONmental -

From the Historiography of the Kamchatka Evens

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 5 (2013 6) 713-719 ~ ~ ~ УДК 9-17.094.2/8:636(571.56) From the Historiography of the Kamchatka Evens Antonina G. Koerkova* M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk 58 Belinskiy Str., Yakutsk, 677980 Russia Received 11.01.2013, received in revised form 26.03.2013, accepted 30.04.2013 The article explores existing researches on the cultural history of the Evens, who belong to small- numbered indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and Far East. The author analyses all the historiographical researches, and classifies them according to the chronology. Keywords: Evens, historiography, small-numbered indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and Far East. The work was fulfilled within the framework of the research financed by the Krasnoyarsk Regional Foundation of Research and Technology Development Support and in accordance with the course schedule of Siberian Federal University as assigned by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation. From the official sources, the Evens as a life of local peoples. The problem of the research nation are known as the Tungus, Evens, Orochis, history and historiography of the Kamchatka Orochel, Orochons, Lamuts. The most widely Evens is that it has not been studied well. There used names are “evyn”, “evysel” which mean are no integrated monographs dedicated to the “local, living here”. The self-designation of the culture of the Kamchatka Evens. Evens and Ovens are widely spread among the Among the authors who were the first to Evens living in Khabarovsk region, Magadan publish some information on the Kamchatka oblast’, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. -

A Case of Chukotka

ISSN 1883-1656 Центр Российских Исследований RRC Working Paper Series No. 71 Demographic Situation and Its Perspectives in the Russian Far East: A Case of Chukotka Kazuhiro KUMO August 2017 RUSSIAN RESEARCH CENTER INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH HITOTSUBASHI UNIVERSITY Kunitachi, Tokyo, JAPAN DEMOGRAPHIC SITUATION AND ITS PERSPECTIVES IN THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST: A CASE OF CHUKОТКА Kazuhiro KUMO 1. INTRODUCTION The purposes of the present study are, first of all, a general review of the population migration patterns in the Far East region of Russia following the demise of the Soviet Union; and secondly, a study of the situation that emerged in the developing regions as a result of the state policy of the Soviet period, using the example of the demographic trends in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug as one of the most distal Russian territories with respect to the center of Russia. To date, several studies have been conducted on inter-regional migration in Russia; by the the author (Kumo, 1997, 2003) a comparative analysis of migration in the post-Soviet Russia was conducted and major changes taking place in the migration patterns were considered in the specified periods. Yu. Andrienko and S. Guriev (Andrienko and Guriev, 2002) performed a comparative analysis of inter-regional migration based on the gravity model and showed that the adoption of the migration decision by the population depended on the regional-economic variables. The results of the above-mentioned studies demonstrate that traditional means of analyzing migration patterns can be applied to Russia, which went through the change in the state system, and the authors conclude that migration flows are largely dependent on economic reasons. -

Social Transition in the North, Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1993

\ / ' . I, , Social Transition.in thb North ' \ / 1 \i 1 I '\ \ I /? ,- - \ I 1 . Volume 1, Number 4 \ I 1 1 I Ethnographic l$ummary: The Chuko tka Region J I / 1 , , ~lexdderI. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. ~dgo~avlensly Ethnographic Summary: The Chukotka Region Alexander I. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. Bogoyavlensky May, 1993 National Economic Forecasting Institute Russian Academy of Sciences Demography & Human Ecology Center Ethnic Demography Laboratory This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DPP-9213l37. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recammendations expressed in this material are those of the author@) and do not ncccssarily reflect the vim of the National Science Foundation. THE CHUKOTKA REGION Table of Contents Page: I . Geography. History and Ethnography of Southeastern Chukotka ............... 1 I.A. Natural and Geographic Conditions ............................. 1 I.A.1.Climate ............................................ 1 I.A.2. Vegetation .........................................3 I.A.3.Fauna ............................................. 3 I1. Ethnohistorical Overview of the Region ................................ 4 IIA Chukchi-Russian Relations in the 17th Century .................... 9 1I.B. The Whaling Period and Increased American Influence in Chukotka ... 13 II.C. Soviets and Socialism in Chukotka ............................ 21 I11 . Traditional Culture and Social Organization of the Chukchis and Eskimos ..... 29 1II.A. Dwelling .............................................. -

Non-Causative Effects of Causative Morphology in Chukchi

Ivan A. Stenin NON-CAUSATIVE EFFECTS OF CAUSATIVE MORPHOLOGY IN CHUKCHI BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: LINGUISTICS WP BRP 59/LNG/2017 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. SERIES: LINGUISTICS Ivan A. Stenin1 NON-CAUSATIVE EFFECTS OF CAUSATIVE MORPHOLOGY IN CHUKCHI2 The paper discusses the main uses of a synthetic causative marker in Chukchi with special reference to non-causative effects of causative morphology. The causative morpheme expresses general causation when attached to patientive intransitive and some agentive intransitive predicates, namely verbs of directed motion, change of posture and ingestion. Other agentive predicates, intransitive as well as transitive, resist causativization and receive some non-causative interpretation if they form causatives. Such causative verbs usually have applicative-like or rearranging functions. JEL Classification: Z. Keywords: causative, applicative, transitivization, rearranging function, Chukchi. 1 National Research University Higher School of Economics. School of Linguistics. Senior Lecturer; E-mail: [email protected]. 2 The paper was prepared within the framework of the Academic Fund Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE) in 2017–2018 (grant № 17-05-0043) and by the Russian Academic Excellence Project «5-100». The author is grateful to all Chukchi speakers who have shared their language knowledge for their patience and generosity. 1. Introduction The paper discusses non-causative effects of causative morphology in Chukchi, a Chukotko- Kamchatkan language spoken in the Russian Far East.