Unsuspected Prevalent Tree Occurrences in High Elevation Sky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limiting Natural Regeneration Potential of Swiss Stone Pine (Pinus Cembra L) in the Northern French Alps

Short note Insect damage to cones and other mortality factors limiting natural regeneration potential of Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra L) in the northern French Alps L Dormont A Roques L Trosset 1 Station de zoologie forestière, CRF-Orléans, INRA, Ardon, 45160 Olivet; 2 Laboratoire dynamique des écosystèmes d’altitude, CISM, campus scientifique, université de Savoie, 73376 Le Bourget-du-Lac cedex, France (Received 21 November 1994; accepted 13 March 1995) Summary — A seed cone population of Swiss stone pine was surveyed from flower bud burst to cone maturation during 1992-1993. The potential seed crop was estimated to decrease by 84 % of the ini- tial value. Mortality was mainly caused by abiotic factors during the first year of cone development while cone insects caused most damage to second-year cones. The cone entomofauna only included three phytophagous species, and largely differed from the fauna observed in cones of other Alpine conifers. Pinus cembra / regeneration / cone insect / seed loss Résumé — Les dégats d’insectes des cônes et autres facteurs de mortalité limitant les poten- tialités de régénération naturelle du pin cembro dans les Alpes françaises du Nord. Un suivi démo- graphique de cônes de pin cembro sur un cycle reproductif complet a été réalisé en 1992 et 1993. Au total, 84 % de la production potentielle de graines a été détruite. La majorité des pertes a été causée par des facteurs abiotiques la première année, et par des insectes pour les cônes de deuxième année. L’entomofaune ne comprend que trois espèces phytophages et diffère largement de celle observée dans les autres essences des conifères alpins. -

Clark's Nutcracker (Nucifraga Columbiana)

PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THREE HIGH LATITUDE RESIDENT CORVIDS: CLARK’S NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA COLUMBIANA), EURASIAN NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA CARYOCATACTES), AND GRAY JAY (PERISOREUS CANADENSIS) KIMBERLY MARGARET DOHMS Bachelor of Science Honours, University of Regina, 2001 Masters of Science, University of Regina, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Biological Sciences University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kimberly M. Dohms, 2016 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THREE HIGH LATITUDE RESIDENT CORVIDS: CLARK’S NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA COLUMBIANA), EURASIAN NUTCRACKER (NUCIFRAGA CARYOCATACTES), AND GRAY JAY (PERISOREUS CANADENSIS) KIMBERLY MARGARET DOHMS Date of Defense: November 30, 2015 Dr. T. Burg Associate Professor Ph.D Supervisor Dr. A. Iwaniuk Associate Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. C. Goater Professor Ph.D Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. D. Logue Assistant Professor Ph.D Internal Examiner Dr. K. Omland Professor Ph.D External Examiner University of Maryland, Baltimore County Baltimore, Maryland Dr. J. Thomas Professor Ph.D Chair, Thesis Examination Committee DEDICATION For the owl and the pussy cat. (And also the centipede.) iii GENERAL ABSTRACT High latitude resident bird species provide an unique opportunity to investigate patterns of postglacial and barrier-mediated dispersal. In this study, multiple genetic markers were used to understand postglacial colonization by and contemporary barriers to gene flow in three corvids. Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), Eurasian nutcracker (N. caryocatactes), and gray jay (Perisoreus canadensis) are year-round resident northern hemisphere passerines with ranges encompassing previously glaciated and unglaciated regions and potential barriers to dispersal (e.g. -

Long-Tailed Duck Clangula Hyemalis and Red-Breasted Goose Branta Ruficollis: Two New Birds for Sichuan, with a Review of Their Distribution in China

138 SHORT NOTES Forktail 28 (2012) Table 1 lists 17 species that have similar global ranges to Bar- Delacour, J. (1930) On the birds collected during the fifth expedition to winged Wren Babbler, and which therefore could conceivably be French Indochina. Ibis (12)6: 564–599. resident in the Hoang Lien Mountains. All these species are resident Delacour, J. & Jabouille, P. (1930) Description de trente oiseaux de in the eastern Himalayas of north-east India, northern Myanmar, l’Indochina Française. L’Oiseau 11: 393–408. and Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China. Species only rarely Delacour, J. & Jabouille, P. (1931) Les oiseaux de l’Indochine française, Tome recorded in northern Myanmar (e.g. Rufous-breasted Accentor III. Paris: Exposition Coloniale Internationale. Prunella strophiata) are excluded, as are those that do not occur in Eames, J. C. & Ericson, P. G. P. (1996) The Björkegren expeditions to French Sichuan (e.g. Grey-sided Laughingthrush Garrulax caerulatus and Indochina: a collection of birds from Vietnam and Cambodia. Nat. Hist. Cachar Wedge-billed Babbler Sphenocichla roberti), although of Bull. Siam Soc. 44: 75–111. course such species might also conceivably occur in Vietnam. Eames, J. C. & Mahood S. P. (2011) Little known Asian bird: White-throated Similarly, species that share a similar distribution to another rare Wren-babbler Rimator pasqueri: Vietnam’s rarest endemic passerine? Fan Si Pan resident—Red-winged Laughingthrush Garrulax BirdingASIA 15: 58–61. formosus—but currently only occur in Sichuan and Yunnan are Kinnear, N. B. (1929) On the birds collected by Mr. H. Stevens in northern excluded, because they do not occur in north-east India and Tonkin in 1923–1924. -

Milieu Cembro.Ai

LaLa ccembraieembraie (pin(pin cembro)cembro) Forests of Swiss Pine 7 Vaccinium myrtillus (myrtille), Vaccinium gaultheroides (airelle à Ericaceae petites feuilles), Ericaceae Ces forêts claires de pin cembro ou arolle (Pinus cembra) se rencontrent à l’étage subalpin, en versant d’ubac et sur silice. Autour du jardin Le Bois des Ayes (commune de Les espèces caractéristiques sont des Ericacées Villard-Saint-Pancrace) est la seule (rhododendron, myrtille, airelle à petites feuilles) et la poacée forêt pure de pin cembro de la Calamagrostis villosa. Le pin cembro se distingue par ses région. Une réserve biologique forestière a été créée en 1990 pour aiguilles groupées par cinq (par deux chez les autres espèces protéger ses arbres pluricentenaires. Pinus cembra (pin cembro, arolle), françaises de pins) et par ses graines qui ne sont pas Dans le massif du Queyras, le bois Pinaceae disséminées par le vent mais par un oiseau, le casse-noix tendre du cembro est utilisé depuis des siècles pour réaliser des meubles moucheté. et des objets sculptés. These open forests of Swiss or Arolla Pine (Pinus cembra) are found in the subalpine zone, on north facing slopes and on acidic substrates. Characteristic species of these forests include species of Ericacea (rhododendron, blueberry, northern bilberry) and the grass Calamagrostis villosa. The Swiss Pine is recognised by its needles being grouped in fives (grouped by two in other pine Nucifraga caryocatactes species in France) and by the fact that its seeds are transported not by wind, (casse-noix), Corvidae © Pierre TOSCANI / Naturimages but by a bird, the spotted nutcracker. LesLes combescombes à nneigeeige Snowbeds 3838 Salix herbacea (saule nain), Soldanella alpina (soldanelle Salicaceae des Alpes), Primulaceae Il s'agit de dépressions qui restent enneigées une grande partie Autour du jardin crête de l'année, suite aux accumulations de neige par le vent. -

Tourist Guide Gauja National Park

EN TOURIST GUIDE GAUJA NATIONAL PARK SIGULDA, LĪGATNE, CĒSIS, VALMIERA, PĀRGAUJA, AMATA, INČUKALNS, KOCĒNI, PRIEKUĻI www.entergauja.com View the most detailed information on travel options in the Gauja National Park at www.entergauja.com TABLE OF CONTENT Gauja National Park 2 • Plan your trip at Gauja National Park, pick natural, cultural and historical objects Gauja Travel Around 3 and add them to your route Spawning of Salmon-like Fish in Gauja National Park 4 • Choose your type of active leisure • Find out the latest information about events and festivals Mushrooms of Gauja National Park 5 • Get information on best hotels, guest houses and campings of the Gauja National Bird Watching in Gauja National Park 6 Park, and make reservations Hiking Routes 7 • Explore the gourmand offers of the restaurants and pubs of the Gauja National Park Sigulda Cycling Routes 10 • View the chosen objects on a map, create and print a PDF file or save a GPX file, and open it on your smartphone Cēsis Cycling Routes 12 • Explore 30 natural tourism routes for walking, cycling, boating and driving Valmiera Cycling Routes 14 • View the weekend and holiday packages Water Routes 16 • View photographs and videos of the selected places • Download tour guides and brochures Enter Nature 17 Enter Action 20 Create your own hike, bike ride or boating route with the routing system Enter Winter 22 that covers roads, paths and rivers in the length of approx. 1800 km Gauja Info 24 Enter Manors 26 Enter History 30 Enter Crafts and Traditional Culture 32 Enter Eco-welness -

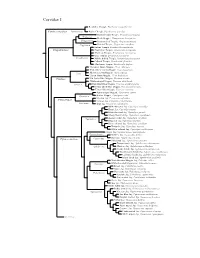

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Eastern China

The magnificent Reeves's Pheasant was one of the many specialties seen on this tour (Brendan Ryan). EASTERN CHINA 3 – 27 MAY 2017 LEADER: HANNU JÄNNES Birdquest’s Eastern China tour, an epic 25 day journey across much of eastern China, focusses on an array of rare Chinese endemics and migrants, and this year’s tour once again proved a great success. The focus of the first part of the tour is to achieve good views of rarities like Spoon-billed Sandpiper, the critically endangered Blue-crowned (Courtois’s) Laughingthrush, the superb Cabot’s Tragopan and Elliot’s Pheasant and the ultra-rare Chinese Crested Tern. This was successfully achieved alongside a plethora of other much sought after species including White-faced Plover, Great Knot, stunning Saunders’s Gulls, Reed Parrotbill, eastern migrants, including Pechora Pipit, Japanese Robin, Japanese Paradise, Yellow-rumped, Narcissus and Mugimaki Flycatchers, and forest species like Brown-chested Jungle Flycatcher, White-necklaced Partridge, Silver Pheasant, Buffy and Moustached Laughingthrushes, Short-tailed Parrotbill, Fork-tailed Sunbird and the delightful Pied Falconet. Quite a haul! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Eastern China 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Crested Ibis at Dongzhai Nature Reserve (Brendan Ryan). The second part of the tour, the ‘Northeast Extension’, visited a series of sites for various other Chinese specialities. Beginning in Wuhan, we bagged the amazing Reeves’s Pheasant and Crested Ibis, as well as stunners that included Fairy Pitta and Chestnut-winged Cuckoo. We then moved on to Jiaocheng for the fabulous Brown Eared Pheasants before flying on to Beijing, where the mountains of the nearby Hebei province yielded the endemic Chinese Beautiful Rosefinch, Chinese Nuthatch, Green-backed and Zappey’s Flycatchers and the rare Grey-sided Thrush. -

Conserving Migratory and Nomadic Species

Conserving migratory and nomadic species Claire Alice Runge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Migration is an incredible phenomenon. Across cultures it moves and inspires us, from the first song of a migratory bird arriving in spring, to the sight of thousands of migratory wildebeest thundering across African plains. Not only important to us as humans, migratory species play a major role in ecosystem functioning across the globe. Migratory species use multiple landscapes and can have dramatically different ecologies across their lifecycle, making huge contributions to resource fluxes and nutrient transport. However, migrants around the world are in decline. In this thesis I examine our conservation response to these declines, exploring how well current approaches account for the unique needs of migratory species, and develop ways to improve on these. The movements of migratory species across time and space make their conservation a multidimensional problem, requiring actions to mitigate threats across jurisdictions, across habitat types and across time. Incorporating such linkages can make a dramatic difference to conservation success, yet migratory species are often treated for the purposes of conservation planning as if they were stationary, ignoring the complex linkages between sites and resources. In this thesis I measure how well existing global conservation networks represent these linkages, discovering major gaps in our current protection of migratory species. I then go on to develop tools for improving conservation of migratory species across two areas: prioritizing actions across species and designing conservation networks. Protected areas are one of our most effective conservation tools, and expanding the global protected area estate remains a priority at an international level. -

29 2008 Bisio Giuntelli I Coleotteri Carabidi Della Val

RIV. PIEM. ST. NAT., 29, 2008: 225-278 LUIGI BISI O * - PIERO GIUNTELL I ** I Coleotteri Carabidi della Val Varaita (Coleoptera Carabidae) ABSTRACT - Carabid beetles of the Varaita Valley (Cottian Alps, Piedmont, Italy) (Coleoptera Carabidae). Results of entomological researches carried out in Varaita Valley (Cuneo, Pied - mont, Italy) are given. A list of 185 carabid beetles species (Cicindelinae included) knows so far from this valley is provided. For each species a list of localities and the patterns of distribution (chorotypes of each species) are also reported. Fur - thermore, the main observed ground beetle assemblages are described. KEY WORDS - Coleoptera Carabidae, Alpine fauna, Western Alps, Piedmont, Varaita Valley. RIASSUNTO - Sono resi noti i risultati di alcune ricerche entomologiche con - dotte in Val Varaita (Cuneo). Viene presentato un elenco di 185 specie di Coleot - teri Carabidi (Cicindelinae incluse) conosciuti sino ad oggi di questa valle. Di ogni specie sono riportati una lista di località e il corotipo di riferimento. Infine ven - gono inoltre descritte le principali carabidocenosi osservate. PREMESSA Dopo tre precedenti contributi dedicati da uno degli autori ad alcune valli delle Alpi Cozie – rispettivamente alla Val Pellice (Bisio, 2001, 2004) e alla Val Germanasca (Bisio, 2007b) –, gli scriventi si occupano nella pre - sente nota dei carabidi (Cicindelinae incluse) della Val Varaita. Nella valle * via Galilei 4 - 10082 Cuorgné (TO) ** via Torino 160 - 10076 Nole Canavese (TO) 225 I coleotteri Carabidi della Val Varaita (Coleoptera Carabidae) in oggetto gli autori stessi, dopo aver condotto ricerche entomologiche in un arco di tempo quasi trentennale – peraltro in modo spesso sporadico e casuale –, hanno effettuato nel corso di tre anni ricerche più capillari e ac - curate, estese a buona parte del territorio vallivo, che hanno consentito di arricchire il già consistente nucleo iniziale di dati posseduti. -

Pine - Wikipedia Visited on 06/20/2017

Pine - Wikipedia Visited on 06/20/2017 Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Pine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents This article is about the tree. For other uses of the term "pine", see Pine (disambiguation). Featured content A pine is any conifer in the genus Pinus, /ˈpiːnuːs/,[1] of the Current events Pine tree family Pinaceae . Pinus is the sole genus in the subfamily Random article Pinoideae. The Plant List compiled by the Royal Botanic Donate to Wikipedia Wikipedia store Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accepts 126 species names of pines as current, together with 35 unresolved Interaction species and many more synonyms.[2] Help About Wikipedia Contents [hide] Community portal 1 Etymology Recent changes 2 Taxonomy, nomenclature and codification Contact page 3 Distribution 4 Description Tools 4.1 Foliage What links here 4.2 Cones Related changes 5 Ecology Upload file 6 Use Special pages 6.1 Farming Permanent link Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora), Page information 6.2 Food North Korea Wikidata item 6.3 Folk Medicine Cite this page 7 See also Scientific classification 8 Notes Kingdom: Plantae Print/export 9 References Division: Pinophyta Create a book 10 Bibliography Class: Pinopsida Download as PDF 11 External links Printable version Order: Pinales In other projects Family: Pinaceae Etymology [edit] Wikimedia Commons Genus: Pinus Wikispecies The modern L. English name pine Subgenera Languages derives from Latin Subgenus Strobus Afrikaans pinus, which some Alemannisch Subgenus Pinus have traced to the Indo-European See Pinus classification for Ænglisc complete taxonomy to species ’base *pīt- ‘resin العربية level. -

The Birdmen of the Pleistocene: on the Relationship Between Neanderthals and Scavenging Birds

Quaternary International xxx (2016) 1e7 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The birdmen of the Pleistocene: On the relationship between Neanderthals and scavenging birds * Stewart Finlayson a, b, , Clive Finlayson b, c a Department of Life Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, East Road, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire CB1 1PT, United Kingdom b Department of Natural History, The Gibraltar Museum, 18-20 Bomb House Lane, Gibraltar c Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, The University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar Museum Associate Campus, 18-20 Bomb House Lane, Gibraltar article info abstract Article history: We have examined 192 Middle Palaeolithic sites in the Palaearctic which have raptor and corvid bones Available online xxx associated in human occupation contexts. We have also examined 395 sites with Upper Palaeolithic contexts for comparison. We show that Neanderthals were regularly associated with a suite of birds of Keywords: prey and corvids. We identify that the main species were regular or seasonal scavengers which co- Neanderthals occurred across large areas of the Neanderthal geographical range. This suggests a long-standing in- Modern humans ter-relationship between Neanderthals, raptors and corvids. We propose that the degree of difficulty of Raptors capturing these species was not an insurmountable problem for the Neanderthals and provide present- Corvids Scavengers day examples of close interaction between scavenging birds and people. We also show that modern Mid-latitude belt humans had a similar relationship with the same suite of birds as the Neanderthals. We suggest that one possibility is that Neanderthals transmitted the behaviour to modern humans. © 2016 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. -

Piedmont, North Italy)

Italian Botanist 5: 57–69Contribution (2018) to the floristic knowledge of the head of the Po Valley... 57 doi: 10.3897/italianbotanist.5.24546 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://italianbotanist.pensoft.net Contribution to the floristic knowledge of the head of the Po Valley (Piedmont, north Italy) Daniela Bouvet1, Annalaura Pistarino2, Adriano Soldano3, Enrico Banfi4, Massimo Barbo5, Fabrizio Bartolucci6,7, Maurizio Bovio8, Laura Cancellieri9, Fabio Conti6,7, Romeo Di Pietro10, Francesco Faraoni11, Simonetta Fascetti12, Gabriele Galasso4, Carmen Gangale13, Edda Lattanzi14, Simonetta Peccenini15, Enrico Vito Perrino16, Roberto Rizzieri Masin17, Vito Antonio Romano12, Leonardo Rosati13, Giovanni Salerno18, Adriano Stinca19,20, Agnese Tilia21, Dimitar Uzunov22 1 Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Viale P.A. Mattioli 25, 10125 Turin, Italy 2 Regional Museum of Natural Sciences, Via G. Giolitti 36, 10123 Turin, Italy 3 Largo Brigata Cagliari 6, 13100 Vercelli, Italy 4 Museum of Natural History, Botanical Department, Corso Venezia 55, 20121 Mi- lan, Italy 5 Via V. Alfieri 10, 33100 Udine, Italy6 School of Biosciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Camerino, Italy 7 Apennines Floristic Research Center, San Colombo, Via Prov.le Km 4,2, 67021 Barisciano (L’Aquila), Italy 8 Via Saint Martin de Corléans 151, 11100 Aosta, Italy 9 Department of Agriculture and Forestry Science, Tuscia University, Via San Camillo de Lellis, 01100 Viterbo, Italy 10 Department of Plan- ning, Design, and Technology of Architecture, Sapienza University of Rome, Via Flaminia 72, 00196 Rome, Italy 11 Via Rubattino 6, 00153 Rome, Italy 12 School of Agricultural, Forestry, Food and Environmental Sciences, Basilicata University, Via Ateneo Lucano 10, 85100 Potenza, Italy 13 Museum of Natural History and Botanic Garden, University of Calabria, Loc.