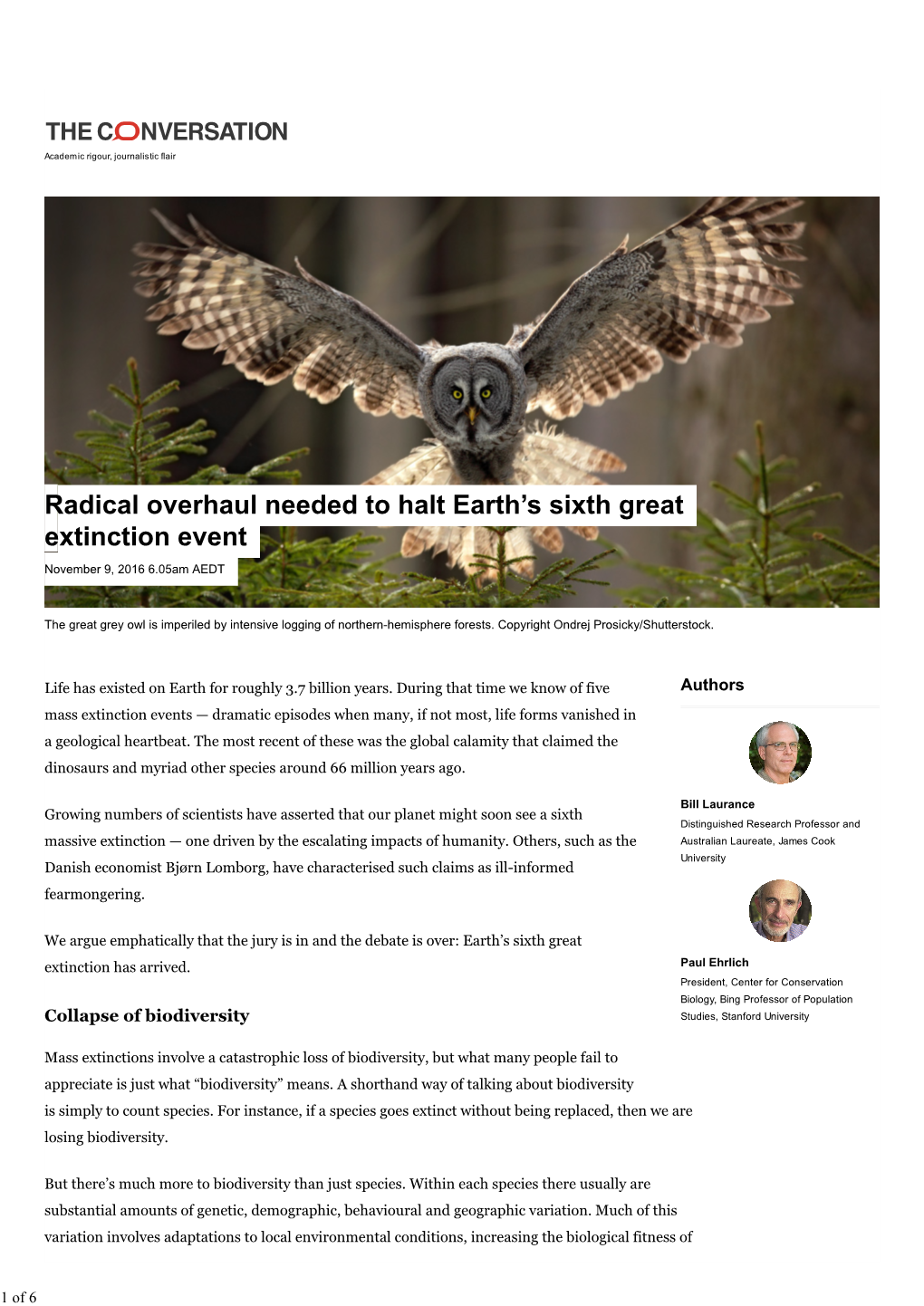

Radical Overhaul Needed to Halt Earth's Sixth Great Extinction Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.CONSERVATION GENETICS. APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Caballero Rúa, Armando CONSERVATION GENETICS. APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY CONCEPTS TO THE CONSERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 4, 2014, pp. 73-77 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511751359009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MONOGRAPH MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 4 (2014): 73-77. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.78.2452 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 01/03/2013, accepted: 02/05/2013. CONSERVATION GENETICS APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY CONCEPTS TO THE CONSERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY ARMANDO CABALLERO RÚA Greater understanding of the forces driving evolutionary change and infl uencing populations, together with the latest genetic analysis techniques, have helped conserve of biodiversity for the last twenty years. This new application of genetics is called conservation genetics. Keywords: genetic drift, inbreeding, extinction vortex, effective population size. One of the most pressing problems caused by human 2012) are the pillars supporting conservation genetics. population growth and the irresponsible use of The launch in 2000 of the journal Conservation natural resources is the conservation of biodiversity. Genetics, dealing specifi cally with this fi eld, and Species are disappearing at a breakneck pace and a more recently, in 2009, of the journal Conservation growing number of them require human intervention Genetics Resources highlight the importance of to optimize their management and ensure their this new application of population and evolutionary survival. -

Genetic and Demographic Dynamics of Small Populations of Silene Latifolia

Heredity (2003) 90, 181–186 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy Genetic and demographic dynamics of small populations of Silene latifolia CM Richards, SN Emery and DE McCauley Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, PO Box 1812, Station B, Nashville, TN 37235, USA Small local populations of Silene alba, a short-lived herbac- populations doubled in size between samples, while others eous plant, were sampled in 1994 and again in 1999. shrank by more than 75%. Similarly, expected heterozygosity Sampling included estimates of population size and genetic and allele number increased by more than two-fold in diversity, as measured at six polymorphic allozyme loci. individual populations and decreased by more than three- When averaged across populations, there was very little fold in others. When population-specific change in number change between samples (about three generations) in and change in measures of genetic diversity were considered population size, measures of within-population genetic together, significant positive correlations were found be- diversity such as number of alleles or expected hetero- tween the demographic and genetic variables. It is specu- zygosity, or in the apportionment of genetic diversity within lated that some populations were released from the and among populations as measured by Fst. However, demographic consequences of inbreeding depression by individual populations changed considerably, both in terms gene flow. of numbers of individuals and genetic composition. Some Heredity (2003) 90, 181–186. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800214 Keywords: genetic diversity; demography; inbreeding depression; gene flow Introduction 1986; Lynch et al, 1995), the interaction of genetics and demography could also influence population persistence How genetics and demography interact to influence in common species, because it is generally accepted that population viability has been a long-standing question in even many abundant species are not uniformly distrib- conservation biology. -

Conservation Biology and Global Change

honeyeater (Melipotes carolae), a species that had never been described before (Figure 56.1). In 2005, a team of American, Indonesian, and Australian biologists experienced many mo- 56 ments like this as they spent a month cataloging the living riches hidden in a remote mountain range in Indonesia. In addition to the honeyeater, they discovered dozens of new frog, butterfly, and plant species, including five new palms. Conservation To date, scientists have described and formally named about 1.8 million species of organisms. Some biologists think Biology and that about 10 million more species currently exist; others es- timate the number to be as high as 100 million. Some of the Global Change greatest concentrations of species are found in the tropics. Unfortunately, tropical forests are being cleared at an alarm- ing rate to make room for and support a burgeoning human population. Rates of deforestation in Indonesia are among the highest in the world (Figure 56.2). What will become of the smoky honeyeater and other newly discovered species in Indonesia if such deforestation continues unchecked? Throughout the biosphere, human activities are altering trophic structures, energy flow, chemical cycling, and natural disturbance—ecosystem processes on which we and all other species depend (see Chapter 55). We have physically altered nearly half of Earth’s land surface, and we use over half of all accessible surface fresh water. In the oceans, stocks of most major fisheries are shrinking because of overharvesting. By some estimates, we may be pushing more species toward ex- tinction than the large asteroid that triggered the mass ex- tinctions at the close of the Cretaceous period 65.5 million years ago (see Figure 25.16). -

Conservation Genetics – Science in the Service of Nature

#0# Acta Biologica 27/2020 | www.wnus.edu.pl/ab | DOI: 10.18276/ab.2020.27-12 | strony 131–141 Conservation genetics – science in the service of nature Cansel Taşkın,1 Jakub Skorupski2 1 Department of Biology, Ankara University, 06930 Ankara, Turkey, ORCID: 0000-0001-6899-701X 2 Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin, Adama Mickiewicza 16 St., 70-383 Szczecin; Polish Society for Conservation Genetics LUTREOLA, Maciejkowa 21 St., 70-374 Szczecin, Poland Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Keywords ecogenomics, extinction risk, extinction vortex, genetic load, genomics, inbreeding depression, management units Abstract Conservation genetics is a subdicipline of conservation biology which deals with the extinction risk and many other problems of nature conservation by using genetic tools and techniques. Conservation genetics is a very good example of the practical use of scientific achievements in nature protection. Although its name seems to be self-defining, its specific area of interest, conceptual apparatus and methodological workshop are not widely known and recognizable. The purpose of this review is to clarify any ambiguities and inconsistencies in this respect. It explore what is conservation genetics, what research and practical issues does it deal with and how they can be solved. Genetyka konserwatorska – nauka w służbie przyrody Słowa kluczowe depresja wsobna, ekogenomika, genomika, jednostki zarządzania, obciążenie genetyczne, ryzyko wyginięcia, wir wymierania Streszczenie Genetyka konserwatorska jest subdyscypliną biologii konserwatorskiej, która zajmuje się ryzykiem wyginięcia gatunków i wieloma innymi problemami ochrony przyrody, przy użyciu narzędzi i technik genetycznych. Genetyka konserwatorska jest bardzo dobrym przykładem praktycznego wykorzystania osiągnięć nauki w ochronie przyrody. -

Conservation Biology Conservation Genetics

DOTTORATO IN SCIENZE AMBIENTALI Genetica e conservazione della biodiversità Ettore Randi Laboratorio di Genetica ISPRA, sede di Ozzano Emilia (BO) Università di Bologna [email protected] giovedì 1 ottobre ore 14:30-17:30 1 genetica, genomica e conservazione della biodiversità 2 conseguenze genetiche della frammentazione venerdì 2 ottobre ore 14:30-17:30 3 ibridazione naturale e antropogenica 4 monitoraggio genetico delle popolazioni naturali Corso di Dottorato in Scienze Ambientali – Università degli Studi di Milano Coordinatore: Prof. Nicola Saino; [email protected] website: http://www.environsci.unimi.it/ Genetica, genomica e conservazione della biodiversità Ettore Randi Laboratorio di Genetica ISPRA, sede di Ozzano Emilia (BO) [email protected] Images dowloaded for non-profit educational presentation use only Transition from conservation GENETICS to conservation GENOMICS Next-generation (massive parallel) sequencing: … not simply more markers Conservation Biology 1980 1986 Conservation Genetics “Conservation genetics: the theory and practice of genetics in the preservation of species as dynamic entities capable of evolving to cope with environmental change to minimize their risk of extinction” Conservation Genetics/Genomics Genetic diversity is the driver and the consequence of biological evolution protection & conservation of biodiversity protection & conservation of the processes & products of evolution The Convention on Biological Diversity CDB Rio de Janeiro 1992 Biodiversity Biodiversity = the diversity -

Understanding Processes of Recovery of the Tibetan Antelope 1 C

Overcoming extinction: understanding processes of recovery of the Tibetan antelope 1 C. LECLERC, C. BELLARD,G.M.LUQUE, AND F. COURCHAMP Ecologie, Syste´matique et Evolution, Centre national de la recherche scientifique UMR CNRS8079, Universite´ Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France Citation: Leclerc, C., C. Bellard, G. M. Luque, and F. Courchamp. 2015. Overcoming extinction: understanding processes of recovery of the Tibetan antelope. Ecosphere 6(9):171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00049.1 Abstract. Since the middle of the 20th century, the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) has been poached for its wool to make luxury shawls, shahtoosh. This direct overexploitation caused a drastic decline in their population, with a loss of more than 90% compared to the baseline population a few decades ago. Assuming this is an anthropogenic Allee effect (AAE), human attraction for rarity can drive rare species to extinction, which could explain the increasing rates of antelope harvests, paralleling the escalating prices of shahtoosh as the species got rarer. Since 1999, international concern led to conservation actions and the population soon started increasing. This unique situation allowed the presence of an AAE in Tibetan antelope to be tested, as well as an assessment of the potential effects of conservation actions in the presence of this process. We developed a theoretical discrete-time population dynamics model and examined effects of variation in shahtoosh prices. Furthermore, we tested the effects of major conservation actions into our models assessing their relative contribution to population recovery. During the exploitation phase, we found some evidence supporting the presence of an AAE compared to non-AAE models when hunting ceased at antelope population sizes below 10% of the initial population size. -

AP Biology Life’S Beginning on Earth According to Scientific Findings (Associated Learning Objectives: 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, 1.12, 1.27, 1.28, 1.29, 1.30, 1.31, and 1.32)

AP Auburn University AP Summer Institute BIOLOGYJuly 11-14, 2016 AP Biology Life’s beginning on Earth according to scientific findings (Associated Learning Objectives: 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, 1.12, 1.27, 1.28, 1.29, 1.30, 1.31, and 1.32) I. The four steps necessary for life to emerge on Earth. (This is according to accepted scientific evidence.) A. First: An abiotic (non-living) synthesis of Amino Acids and Nucleic Acids must occur. 1. The RNA molecule is believed to have evolved first. It is not as molecularly stable as DNA though. 2. The Nucleic Acids (DNA or RNA) are essential for storing, retrieving, or conveying by inheritance molecular information on constructing the components of living cells.. 3. The Amino Acids, the building blocks of proteins, are needed to construct the “work horse” molecules of a cell. a. The majority of a cell or organism, in biomass (dry weight of an organism), is mostly protein. B. Second: Monomers must be able to join together to form more complex polymers using energy that is obtained from the surrounding environment. 1. Seen in monosaccharides (simple sugars) making polysaccharides (For energy storage or cell walls of plants.) 2. Seen in the making of phospholipids for cell membranes. 3. Seen in the making of messenger RNA used in making proteins using Amino Acids. 4. Seen in making chromosomes out of strings of DNA molecules. (For information storage.) C. Third: The RNA/DNA molecules form and gain the ability to reproduce and stabilize by using chemical bonds and complimentary bonding. -

Relation of Minimum Viable Population Size to Biology, Time Frame, and Objective

Comment Relation of Minimum Viable Population Size to Biology, Time Frame, and Objective J. MICHAEL REED∗ § AND EARL D. MCCOY† ∗Department of Biology, Tufts University, Medford, MA, 02155, U.S.A. †Department of Integrative Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, 33620, U.S.A. Shoemaker et al.’s (2013) estimate of the minimum vi- probability of extinction escalates dramatically over 40 able population size (MVPS) of the bog turtle (Glyptemys generations (Fig. 1). Given the long generation length, muhlenbergii) is 3 orders of magnitude below popu- 20–30 years, of the bog turtle, Shoemaker et al.’s result lation sizes typically viewed as minimally viable (Reed is, therefore, not surprising; but, it is inconsistent with et al. 2003; Trail et al. 2007). Even Flather et al. (2011), typical conception of MVPS, which assumes a population who question the utility of MVPS for conservation plan- will be self-sustaining. Similarly, Brook et al. (1999) con- ning, concede that long-term persistent populations will cluded a high probability of persistence for 50 years for require thousands of individuals. Rather than conclude a population of 18 Whooping Cranes (Grus americana). their result is incorrect, Shoemaker at al. suggest that Because Whooping Cranes can live for 35 years, it is MVPS has been overestimated for long-lived species. Al- unlikely that any pair of birds that can reproduce would though we agree in principle that small populations, es- fail to produce a lineage that persisted 50 years; but, 18 pecially of long-lived species, have conservation value, individuals do not necessarily constitute a viable popu- we do not agree that Shoemaker et al.’s result provides lation. -

Forecasting Extinctions: Uncertainties and Limitations

Diversity 2009, 1, 133-150; doi:10.3390/d1020133 OPEN ACCESS diversity ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Review Forecasting Extinctions: Uncertainties and Limitations Richard J. Ladle 1,2 1 School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford University, South Parks Road, Oxford, UK; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-31-3899 1902; Fax: +55-31-3899-2735 2 Department of Agricultural and Environmental Engineering, Federal University of Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil Received: 13 October 2009 / Accepted: 14 November 2009 / Published: 26 November 2009 Abstract: Extinction forecasting is one of the most important and challenging areas of conservation biology. Overestimates of extinction rates or the extinction risk of a particular species instigate accusations of hype and overblown conservation rhetoric. Conversely, underestimates may result in limited resources being allocated to other species/habitats perceived as being at greater risk. In this paper I review extinction models and identify the key sources of uncertainty for each. All reviewed methods which claim to estimate extinction probabilities have severe limitations, independent of if they are based on ecological theory or on rather subjective expert judgments. Keywords: extinction; uncertainty; forecasting; local extinction; viability 1. Introduction ―Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future‖ Nils Bohr, Nobel Prize winning physicist Preventing the extinction of species is probably the most emblematic objective of the global conservation movement. To fulfill this aim effectively requires that decision makers and environmental managers are provided with accurate information on: (1) the identities of specific species/populations with a high probability of going extinct without further interventions; (2) the predicted rates of extinction among a range of taxa in different geographic areas and biomes under various ecological scenarios. -

The Extinction Vortex

Chapter 56 Conservation Biology and Restoration Ecology PowerPoint® Lecture Presentations for Biology Eighth Edition Neil Campbell and Jane Reece Lectures by Chris Romero, updated by Erin Barley with contributions from Joan Sharp Copyright © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Benjamin Cummings Key concepts 1. Apply the knowledge of ecology to have sustainable biosphere. 2. We are most likely to protect what we appreciate, and we are most likely to appreciate what we understand. Copyright © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Benjamin Cummings Overview: Striking Gold • 1.8 million species have been named and described • Biologists estimate 10–200 million species exist on Earth • Tropical forests contain some of the greatest concentrations of species and are being destroyed at an alarming rate • Humans are rapidly pushing many species toward extinction Copyright © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Benjamin Cummings Fig. 56-1 What will be the fate of this newly described bird species? Fig. 56-2 Tropical deforestation in West Kalimantan, an Indonesian province • Conservation biology, which seeks to preserve life, integrates several fields: – Ecology – Physiology – Molecular biology – Genetics – Evolutionary biology Copyright © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Benjamin Cummings • Restoration ecology applies ecological principles to return degraded ecosystems to conditions as similar as possible to their natural state Copyright © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Pearson Benjamin Cummings Fig. 56-3 Biodiversity has three main components Genetic diversity in a vole population Species diversity in a coastal redwood ecosystem Community and ecosystem diversity across the landscape of an entire region Species Diversity • Species diversity is the variety of species in an ecosystem or throughout the biosphere • According to the U.S. -

Lessons for Conservation Eric Isaí Ameca Y Juárez

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Spiral - Imperial College Digital Repository Natural population die-offs: lessons for conservation Eric Isaí Ameca y Juárez A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the Division of Biology, Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London Contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements Chapter 1 12 Natural population die-offs: causes and consequences for terrestrial mammals Extreme natural events and biodiversity loss Defining abnormally high population losses Extreme natural events, species biology & incidence of natural population die-offs Predicting vulnerability to natural population die-offs Natural population die-offs, climate change & the implications for conservation Chapter 2 23 Identifying species biological characteristics shaping natural population die-offs Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Chapter 3 37 Assessing exposure to extreme climatic events for terrestrial mammals Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion 2 | P a g e Chapter 4 50 Vulnerability assessment to cyclone-driven population declines: an implementation for Mexican terrestrial endangered mammals Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Chapter 5 62 Quantifying the impact of cyclones on extinction probability of a primate population: insights into island extirpations Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusions 78 List of references 83 List of tables 114 Table 1.1 Examples of extreme natural events reported -

Part I Introduction

PA R T I Introduction COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CHAPTER 1 Introduction One - horned rhinoceros, Section 5.3 We are at a critical juncture for the conservation and study of biological diversity: such an opportunity will never occur again. Understanding and maintaining that diversity is the key to humanity ’ s continued prosperous and stable existence on Earth. US National Science Board Committee on Global Biodiversity (1989) The extinction of species, each one a pilgrim of four billion years of evolution, is an irreversible loss. The ending of the lines of so many creatures with whom we have traveled this far is an occasion of profound sorrow and grief. Death can be accepted and to some degree transformed. But the loss of lineages and all their future young is not something to accept. It must be rigorously and intelligently resisted. Gary Snyder (1990) Chapter Contents 1.1 Genetics and civilization, 4 1.2 What should we conserve? 5 1.3 How should we conserve biodiversity? 9 1.4 Applications of genetics to conservation, 10 1.5 The future, 12 Guest Box 1 The role of genetics in conservation, 13 Conservation and the Genetics of Populations‚ Second Edition. Fred W. Allendorf, Gordon Luikart, and Sally N. Aitken. © 2013 Fred W. Allendorf, Gordon Luikart and Sally N. Aitken. Published 2013 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 4 Introduction We are living in a time of unprecedented extinctions tion of plants is thought to have been perhaps the key (Myers and Knoll 2001 , Stuart et al . 2010 , Barnosky step in the development of civilization (Diamond et al . 2011 ).