AHR Forum Ethnicity, Indigeneity, and Migration in the Advent of British Rule to Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Poetical Sketches of the Interior of Ceylon

Poetical Sketches of the Interior of Ceylon Benjamin Bailey (1791-1853), aged 26 years Framed colour portrait by an anonymous artist Courtesy: Keats catalogue, London Metropolitan Archives "One of the noblest men alive at the present day" was John Keats's description of Bailey Poetical Sketches of the Interior of the Island of Ceylon Benjamin Bailey's Original manuscript, 1841 Introduction: Rajpal K de Silva, 2011 Serendib Publications London 2011 Copyright:© Rajpal Kumar de Silva, 2011 ISBN 978-955-0810-00-0 Published by: Serendib Publications 3 Ingleby Court Compton Road London N21 3NT England Typesetting / Printing Lazergraphic (Pvt) Ltd 14 Sulaiman Terrace Colombo 5 Sri Lanka iv CONTENTS Acknowledgements Foreword: Professor Emeritus Ashley Halpe Benjamin Bailey as a friend of John Keats: Professor Robert S White Benjamin Bailey, (1791 — 1853) Preface The Manuscript Present publication Some useful sources Introduction Biography Bailey's personality Bailey and Keats Bailey's poetry Ecclesiastical appointments Courtship and marriage Later in France Bailey in Ceylon Appendices I England during Bailey's era Early British Colonial rule in Ceylon II The Church Missionary Society, (CMS) CMS in Ceylon and Kottayam Comparative resumes of the two Baileys III Benjamin Bailey, Scrapbook Guide: Harvard University, USA IV Keats House Museum, Hampstead, London V St Peter's Church, Fort, Colombo: Bailey Memorials VI Six letters of Vetus in the Ceylon Times, 1852 Benjamin Bailey: Poetical Sketches of the Interior of the Island of Ceylon Part I -- Preface, Sonnets and Notes Part II -- Sonnets and Notes Part III -- Sonnets, Poems, Stanzas, Appendix and Notes Notes Bibliography V Acknowledgements Benjamin Bailey's manuscript of 1841 would probably have faded into oblivion had it not been for my chancing to pick it up in an antiquarian bookstore. -

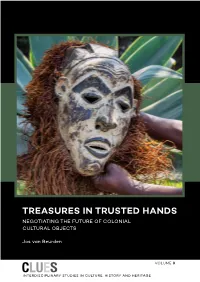

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

A Brief Account of Ceylon

Ol'h lERrElEV IBRARY ^IVER^fTY OF ::alifornia h •^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/briefaccountofceOOIiesrich ..sr" r^' BRIEF ACCOUNT OF CEYLON, BY L. F. LIESCHING, CETLON CIVIL SERVICE. m And India's utmost isle, Taprobane.—-Miltoit. Jaffna: RIPLEVr & STRONG,—PRINTERS 1861. ^>^' LOAN STACK TO Sir Charles J. MacCartht, GOVERNOR AND COMM J^NDER-IN-CHIKf OF THE Island of Ceyloa and its Dependencies, &:C,, &c., kt. This work is hy 'permission dedicated^ with much respect^ by His Excellency's Obedient Servant^ THE WRITER, Ubi Taprobanen IndJca cingit aqua. CONTESTS, INTRODUCTION Vll. CHAPTER I. GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION, CLI- MATE, SCENERY, &C. OF (M^^VLON, 1 11. INHABITANTS AND RESIDENTS, 16 III. ANIMALS, VEGETABLES, AND MINERALS, 32 IV. HISTORICAL SKETCH, 38 V, ANTIQUITIES, Ill '' VL RELIGION, EDUCATION, LITER- ATURE, 126 '''- VII. TRADE AND REVENUE, 148 • VIII. CONCLUSION, 15L APPENDIX, 154 GLOSSART. Da'goba, a bell shaped monumei]i ^moky Budha. Pansala, the monastic residence '-.f Bndhu,: priesi:; Wiha ra, a Budhist temple. INTEOBUCTIOS. __ MERsoN Tennent has made tlie remark, liat more works liavebeenpublislied on Cey- nu than on any other island in the world, vUgland itself not excepted. Such being the a>( ,the question may naturally he asked why : should have been thought necessary to add M)thenumber. To this we would reply iv book of a general character, has been en with a special view to the wants of iglit tube chiefly interested in an 1 tlie islaiid.—namely, the sons of the .M the British Government has ex- benefits of European learning to its : vbjecls,'- -^vhile the various missionary ive largely employed education as a v'ards j-.ecuring their great end,—and recipients of these benefits have d<^sciibe geographically, most conn- .: rhe* worhl, and to give a historical ac- 'id of {^^everal of them, they know little or VIII INTRODUCTION. -

Jesty, Is Pleased to Ckclarte Aucloofestituiey Those Whose

[.48 ] jesty, is pleased to ckclarte aucloofestituiey those 49. Admiral Sir William whose names are und4rtii£n(tianedy to be the 50. Geoieral the Hereditary Prince'of Orange. Knights Grand Crosses^ jcompostog -the'" Fiist 51. Admiral Lord \iHse$«»t^ Hood. Class of the Most Hpaontable Military > Order -of 52. Admiral>Sir Ritefrard Oufelow, Bart. the Bath. ,\^" •„ / ; 53. Admiral the Ho3jourii>le AVilliam Cornwallis. Military Knights Grctnd' v Civil KnighM Grand 54.'Admiral Lord Rad&tock. " Crosses. .• , Crosses. 55. Admiral Sir Roger Curtis, Bart. 1 . The Sovereign. 56. LicutenantVGeiveral'-the Earl of "Uxbridge. J. His Royal Highness 57. Lieutenant-General Robert Brownrigg. the Duke of York, 5S.. Lieutenant-General Barry Calvert. Acting as Grand 59. Lieutenant-General the Right Honourable Tho* Master,. masMaitland.- « ..•-.- •, Sir Rober GO. LieuteoautrGeneral William Heixry CliHton. .. •" t- St. Vincehty 9th. And His Royal Highness the Prince Regent 4. General 'Sir Rottert TbeEfarlofMalines- is further pleased to ordain and declare, that the Abereromby. •!. bury. Princes of the Blood Royal holding Commissions S.Adni.ViscountKeith; ' 8! Lord Henly. as General Officers in His Majesty's Army, or as 6. Admiral Sir John B. 4. Lord Whit \vortb. Flag-Officers in the Royal Navy, now and hereafter Warren, Bart. may be nominated and appointed Knights Grand 7. General Sir Alured -Sir Joseph Bapkes, Crosses of tiie MosX, Honourable Military Order Clarke. • i •* of the Bath, apd SjiialtUQt, t>e included in the num- 8. Admiral Sir John $! Right Hon. Sir Ar- J< ber to which the First Class of the Order is Colpoys. • thur Paget. limited by the third article of the present "instru- 9. -

King Vijaya (B.C

King Vijaya (B.C. 543-504) and his successors (Source: A SHORT HISTORY OF LANKA by Humphry William Codrington) The traditional first king of Lanka is Vijaya. His grandmother, Suppadevi, according to the legend was the daughter of the king of Vanga (Bengal) by a princess of Kalinga (Orissa). She ran away from home and in the country of Lala or Lada, the modern Gujarat, mated with a lion (sinha); hence the names of her children and ultimately that of Sinhala, the designation of Lanka and of the Sinhala. At the age of sixteen her son Sinhabahu carried off his mother and his twin sister to the haunts of men; the lion in his search for his family ravaged the country, and for the sake of the reward offered by the king of Vanga was slain by his own son. The king dying at the time, Sinhabahu was elected as his successor, but abandoned Vanga and built the city of Sinhapura in his native country Lada. His son Prince Vijaya and his boon companions committed such outrages in his father's capital that the king was compelled by popular clamour to drive them forth. They set sail and, touching at Supparaka, a famous port on the west coast of India (Sopara, north of Bombay), ultimately arrived at Tambapanni. Vijaya is made to land at Tambapanni on the very day of Buddha's death. Here they found the country inhabited by Yakkhas or demons, and one of them Kuveni, entrapped Vijaya's followers, but was compelled by the prince to release them. -

BAA July 2016 Newsletter for Web.Cdr

BURGHER ASSOCIATION (AUSTRALIA) INC Postal Address: PO Box 75 Clarinda VIC 3169 ABN - 28 890 322 651 ~ INC. REG. NO. A 0007821F Web Site: http://www.burgherassocn.org.au July 2016 Winter News Bulletin Sponsored by Victorian Multicultural Commission COMMITTEE OF MANAGEMENT 2015/16 President Mr Hermann Loos - 03 9827 4455 hermann r [email protected] Vice President Mrs Tamaris Lourensz - 03 5981 8187 [email protected] Secretary Mr Harvey Foenander - 03 8790 1610 [email protected] Assistant Secretary Mrs Rosemary Quyn - 03 9563 7298 [email protected] Treasurer Vacant Assistant Treasurer Mr Tyrone Pereira - 0418 362 845 [email protected] Editor Mr Neville Davidson - 03 97111 922 [email protected] Public Relations Manager Mrs Elaine Jansz - 03 9798 6315 [email protected] Premises Manager Mr Bevill Jansz - 03 9798 6315 [email protected] Customer Relations Manager Mrs Breeda Foenander - 03 8790 1610 [email protected] COMMITTEE Mrs Carol Loos - 03 9827 4455 Mr Christopher Felsinger - 03 9512 7484 Mr Fred Clarke - 03 8759 0920 Mrs Dyan Davidson - 03 97111 922 Cecil Balmond Sri Lankan born internationally renowned architectural maestro Cecil Balmond OBE of Sri Lankan origin is feted as one of the world's leading thinkers on form and structure and widely considered to be one of the most significant creators of his generation. Pioneering a new approach in the crossover between advanced art and science Cecil heads Balmond Studio in London, a research led practice of architects, designers, artists and theoreticians who apply Cecil's revolutionary non-linear, generative methods to create extraordinary designs that fundamentally reorganise space. -

BUDDHISM and CHRISTIANITY in CEYLON (1796 - 194.6)

^ l \ <A BUDDHISM and CHRISTIANITY in CEYLON (1796 - 194.6) by Charles Winston Karimaratna L.Th., B.D., II. Th., Ph.D. Fellov/ of The Philosophical Society, Fellow of.The Royal Society of Arts. Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology in the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1974 . "Buddhist/Christian Relationships in British Ceylon 1796/1948" "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; A good understanding have all those who practise it." Psalm 111 : 10. "That men may know wisdom and instruction, understand words of insight, receive instruction in wise dealing, righteousness, justice and equity; that prudence may be given to the simple, knowledge and discretion to the y o u t h ..... the wise man also may hear and increase in learning, and the man of understanding acquire skill." Proverbs 1 : 1*5. Dedicated to Muriel, m y wife, supporter, critic and well-wisher. ProQuest Number: 11010359 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010359 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

THE FALL of the KANDYAN KINGDOM in the Preceding

Dutch and British colonial intervention in Sri Lanka, 1780 - 1815: expansion and reform Schrikker, A.F. Citation Schrikker, A. F. (2007). Dutch and British colonial intervention in Sri Lanka, 1780 - 1815: expansion and reform. Leiden: Brill. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/5419 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/5419 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 197 CHAPTER ELEVEN THE COLONIAL PROJECT COMPLETED: THE FALL OF THE KANDYAN KINGDOM In the preceding chapters on the development of British policies on the island, Kandy was discussed only sporadically, but it certainly deserves more attention. If we can identify Governor Maitland as the one who laid the foundation of the definite reorganization of the British administra- tion, his successor Robert Brownrigg should be singled out as the gover- nor who took care of the formal political unification of the island under the British flag in 1815, thereby completing the colonial project in Ceylon. A lot has been written about the fall of the Kingdom of Kandy and it is usually seen as an isolated incident that came about as a result of either British expansionist attitudes or the tyranny of the last king. However, as has been pointed earlier, the Kingdom suffered from contin- uous political tension in the late eighteenth century, and this tempted cer- tain nobles to intrigue with Van de Graaff. At the same time, the Dutch Governor thought that the acquisition of the Kandyan territories could solve his financial troubles and increase the necessary agricultural output to feed the labourers on the plantations and the soldiers in the garrisons on the coast. -

Text Book 1.1 File

Figure 1.1 Trincomalee Harbour Commercial Activities “From the point of view of European traders, it could be said that the importance of the island lay in the fact that it was the main source of cinnamon produced in the Eastern World” For free distribution 2 From this statement you would be able to gather an important cause which prompted the British, to consider Sri Lanka as an important country. Cinnamon was only one of the main commercial commodities which could be p rocured from this country. In addition, spices such as nutmegs, pepper, cardamom and cloves and other items such as pearls, precious stones and elephant tusks were among the main commodities which the Europeans sought from Sri Lanka. The British realized that the establishment of their power in the island would be the best means of ensuring the access to these items. Establishment of British Power in the Maritime Provinces of Sri Lanka We know that the French Revolution commenced in 1789. During the course of the revolution France which opposed the monarchies in other countries of Europe, too, invaded Holland. In the face of this invasion, Prince William V, the Stadtholder or the ruler of Holland fled to England. The British, who were anxious to gain control over Sri Lanka, used this opportunity and obtained a letter from the Dutch ruler, to be presented to the Dutch Governor in Sri Lanka. He was instructed " to allow the British to take possession of the Dutch territories in Sri Lanka in order to prevent them from falling into the hands of the French . -

'The Belfast Chameleon': Ulster, Ceylon and the Imperial Life of Sir

Britain and the World 6.2 (2013): 192–219 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE DOI: 10.3366/brw.2013.0096 # Edinburgh University Press provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library www.euppublishing.com/brw Print ISSN: 2043-8567; online ISSN: 2043-8575 ‘The Belfast Chameleon’: Ulster, Ceylon and the Imperial Life of Sir James Emerson Tennent Jonathan Jeffrey Wright1 Late in 1844, The Economist carried a pithy report, reflecting on one of the more curious episodes in the life of the Belfast-born writer, parliamentarian and colonial administrator James Emerson Tennent – his capture, and subsequent donation to the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society (BNHPS), of a live chameleon. The Belfast papers state that Mr. Tennent, M.P., has sent over to their Natural History Society a Cameleon [sic], which he caught on Mount Calvary, and that it is still alive in the Museum. Strange how it should occur to the Honourable Member to present such a reptile to his constituents, as a memorial of their connection with him!2 Brief as it, this report intrigues on a number of levels. For the biographer, the pointed reference to the fact that it was ‘such a reptile’ as a chameleon that Emerson Tennent had presented to his constituents is telling, highlighting the fact that he was a viewed, in some quarters, as changeable and untrustworthy. More broadly, the report foregrounds the globally connected nature of the 1 Jonathan Jeffrey Wright is a postdoctoral research fellow on the Scientific Metropolis Project at Queen’s University Belfast. -

The Ceylon Calendar for ... 1827

% / THE f CEYLON CALENDAR FOE THE rear of Ow Lore il C33 <&al 4 © COLOMBO Feinted at the Government Press Rv NICHOLAS BERGMAN. w. Jr I A •m VQ> i i 9 . Afi| « « * INDEX Page almanac ~ ~ - 16? Adjutant General’s Office - 91 Advocate Fiscal’s Office — - 169 Apothecary to the Forces, Office of — - 96 Arch Deacon of Colombo — — - 152 Army serving in Ceylon — - 152 Artillery Royal — — “T - 95 Auditor and Accountant General s Omce — — - 138 Batt.icaloa Collectorship — — _ 139 Batticaloa Provincial Court — — - 144 Society — — — Bible - 272 Births in 1826 — - 93 Bookbinder’s Office — — ’ - 98 Botanic Garden •— — 136 Oalpentyn Provincial Court — — - 136 Calpentyn Magistracy — — - 112 Caltura Magistracy — — — - — 217 Carts & Coolies, Regulation for 152 Ceylon Dragoons — — — "”* 212 Ceylon Money, Weights &c. — — Office — - - — 92 Chief Secretary’s 7 Chilaw Putlam & Calpentyn Collectorship — 134 101 Civil Fund Committee — — — — Cinnamon Department — — - 98 Civil Servants General List of — - 140 Civil Servants retired on Pensions *-=• - 143 Civil Servants on leave of absence '*“• - 143 Colombo Collectorship — -— — - 101 Colombo Provincial Court — —• — - 110 Colombo Magistracy — — — 112 Colombo Custom House — — Ill Colombo Master Attendant’s Office — Ill Colombo Port Charges — — — 258 Colonial Engineer and Land Surveyor Department — 100 Colonial Agents — — 168 Colonial Chaplains — — — 96 Commandants & Staff of Garrisons — 149 Commissariat Establishment — — 167 Commissioner of Revenue’s Office — — 94 Commons, House of — — — 61 Council — — — — 89 Colonial