Poetical Sketches of the Interior of Ceylon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Audiobooks 1/1/05 - 5/31/05

NEW AUDIOBOOKS 1/1/05 - 5/31/05 AVRCU = AUDIOBOOK ON CASSETTE AVRDU = AUDIOBOOK ON COMPACT DISC [ 1] Shepherds abiding :with Esther's gift and the Mitford snowmen /by Jan Karon. AVRCU3876 Karon, Jan,1937- [ 2] Kill the messenger /by Tami Hoag. AVRCU3889 Hoag, Tami. [ 3] Voices of the Shoah :remembrances of the Holocaust /[written by David Notowitz]. AVRDU0352 [ 4] We're just like you, only prettier :confessions of a tarnished southern belle /Celia Rivenbark. AVRCU4020 Rivenbark, Celia. [ 5] A mighty heart /by Mariane Pearl with Sarah Crichton ; narrated by Suzanne Toren. AVRCU4025 Pearl, Mariane. [ 6] The happiest toddler on the block :the new way to stop the daily battle of wills and raise a secure and well-behaved one- to four-year-old /Harvey Karp with Paula Spencer. AVRCU4026 Karp, Harvey. [ 7] Black water /T.J. MacGregor. AVRCU4027 MacGregor, T. J. [ 8] A rage for glory :the life of Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN /James Tertius de Kay. AVRCU4028 De Kay, James T. [ 9] Affinity /Sarah Waters. AVRCU4029 Waters, Sarah,1966- [ 10] Dirty laundry /Paul Thomas. AVRCU4030 Thomas, Paul,1951- [ 11] Horizon storms /Kevin J. Anderson. AVRCU4031 Anderson, Kevin J.,1962- [ 12] Blue blood /Edward Conlon. AVRCU4032 Conlon, Edward,1965- [ 13] Washington's crossing /by David Hackett Fischer. AVRCU4033 Fischer, David Hackett,1935- [ 14] Little children /Tom Perrotta. AVRCU4035 Perrotta, Tom,1961- [ 15] Above and beyond /Sandra Brown. AVRCU4036 Brown, Sandra,1948- [ 16] Reading Lolita in Tehran /by Azar Nafisi. AVRCU4037 Nafisi, Azar. [ 17] Thunder run :the armored strike to capture Baghdad /David Zucchino. AVRCU4038 Zucchino, David. [ 18] The Sunday philosophy club /Alexander McCall Smith. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Inculturating Liturgy in Sri Lanka: Contextualization in the Church Of

Inculturating Liturgy in Sri Lanka: Contextualization in the Church of Ceylon by Phillip Tovey (ed.) and Rasika Abeysinge Marc Billimoria Keerthisiri Fernando Narme Wickremesinghe The sanctuary of Christ Church Baddegama. The cover picture is of Trinity College Chapel Kandy, both © Phillip Tovey. ISSN: 0951-2667 ISBN: 978-0-334-05966-0 Contents 1 Introduction 4 Phillip Tovey 2 The Sri Lankan Context: History & 6 Social Setting and the Church’s Attitudes to Local Cultures, Religions, Ideologies Keerthisiri Fernando and Rasika Abeysinghe 3 The Ceylon Liturgy 17 Phillip Tovey 4 Alternative Contextualization: The New 33 World Liturgy and the Workers Mass Marc Billimoria 5 Examples of Contextualization in Current 46 Liturgies Narme Wickremesinghe 6 Bibliography 62 3 1 Introduction Phillip Tovey The Church of Ceylon is two dioceses extra-provincial to Canterbury but governed by a single General Assembly (synod). It has a rich history of inculturation of the liturgy. This story is not well known, and the purpose of this book is to tell the story to the rest of the Anglican Communion and the wider church. Sri Lanka has a unique mixture of cultures and religions, Buddhist and Hindu, in which the Christian church has developed. There has also been a context of strong socialist ideology. It is in this context that the church lives. Is the church to be in a westernised form requiring people to abandon their culture, if they wish to become Christians? This question has been wrestled with for almost a century. Out of religious and ideological dialogue the church has developed liturgical forms that help shape Sri Lankan Christians (rather than Christians in Sri Lanka). -

Rearticulations of Enmity and Belonging in Postwar Sri Lanka

BUDDHIST NATIONALISM AND CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM: REARTICULATIONS OF ENMITY AND BELONGING IN POSTWAR SRI LANKA by Neena Mahadev A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 © 2013 Neena Mahadev All Rights Reserved Abstract: Based on two years of fieldwork in Sri Lanka, this dissertation systematically examines the mutual skepticism that Buddhist nationalists and Christian evangelists express towards one another in the context of disputes over religious conversion. Focusing on the period from the mid-1990s until present, this ethnography elucidates the shifting politics of nationalist perception in Sri Lanka, and illustrates how Sinhala Buddhist populists have increasingly come to view conversion to Christianity as generating anti-national and anti-Buddhist subjects within the Sri Lankan citizenry. The author shows how the shift in the politics of identitarian perception has been contingent upon several critical events over the last decade: First, the death of a Buddhist monk, which Sinhala Buddhist populists have widely attributed to a broader Christian conspiracy to destroy Buddhism. Second, following the 2004 tsunami, massive influxes of humanitarian aid—most of which was secular, but some of which was connected to opportunistic efforts to evangelize—unsettled the lines between the interested religious charity and the disinterested secular giving. Third, the closure of 25 years of a brutal war between the Sri Lankan government forces and the ethnic minority insurgent group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), has opened up a slew of humanitarian criticism from the international community, which Sinhala Buddhist populist activists surmise to be a product of Western, Christian, neo-colonial influences. -

November 2009 Newsletter

November 09 Newsletter ------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records PO Box 54 Miranda NSW 2228 Phone/fax: (02)95311710 Email:[email protected] Web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------ Postage: 1cd $2/ 2cds 3-4 cds $6.50 ------------------------------------------------ Loudon Wainwright III “High Wide & Handsome – The Charlie Poole Project” 2cds $35. If you have any passion at all for bluegrass or old timey music then this will be (hands down) your album of the year. Loudon Wainwright is an artist I have long admired since I heard a song called “Samson and the Warden” (a wonderfully witty tale of a guy who doesn’t mind being in gaol so long as the warden doesn’t cut his hair) on an ABC radio show called “Room to Move” many years ago. A few years later he had his one and only “hit” with the novelty “Dead Skunk”. Now Loudon pundits will compare the instrumentation on this album with that on that song, and if a real pundit with that of his “The Swimming Song”. The backing is restrained. Banjo (Poole’s own instrument of choice), with guitar, some great mandolin (from Chris Thile) some fiddle (multi instrumentalist David Mansfield), some piano and harmonica and on a couple of tracks some horns. Now, Charlie Poole to the uninitiated was a major star in the very early days of country music. He is said to have pursued a musical career so he wouldn’t have to work and at the same time he could ensure his primary source of income, bootleg liquor, was properly distilled. He was no writer and adapted songs he had heard to his style. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

THE NINETY-SIXTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions PRESENTED AT THE MEETING HELD AT NORTH ADAMS AND WILLIAMSTOWN, MASS. O c t o b e r 9- 1 2 , 1 9 0 6 PUBLISHED BY THE BOARD C ongregational H o u s e BOSTON Thomas Todd Printer CONTENTS P a g e P a g e The Missions M i n u t e s o f t h e A n n u a l M e e t i n g . v West Central African M ission ......................... 33 Corporate Members P resen t ............... v East Central African M ission .............................. 39 Male Honorary Members Reported as Present vii Zulu M ission .......................................................... 44 Missionaries Present............................... viii European Turkey M ission ................................. 51 Organization................................................ viii Western Turkey M ission ..................................... 60 Committees Appointed ........................... ix-xi Central Turkey M ission ...................................... 74 Resolutions .................................................. ix-xvii Eastern Turkey M ission ..................................... 84r New Members........................................... xiii Marathi Mission ............................... 93 Annual Serm on ........................................ x Madura M ission ...................................................... 10T Place and Preacher for Next Meeting . xiv Ceylon M ission ...................................................... 117 Election of Officers.................................. -

Report R Esumes

REPORTR ESUMES ED 1)17 546 TE 499 996 DEVELOPMENT AND TRIAL IN A JUNIOR AND SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL OF A TWO VEAP CURRICULUM IN GENERAL MUSIC. BY- REIMER, BENNETT CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIV., CLEVELAND, OHIO REPORT NUMBER ti-116 PUB DATE AUG 67 REPORT NUMBER BR -5 -0257 CONTRAC% OEC6-10-096 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.75 HC-617.56 437P. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT, *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *MUSIC EDUCATION, *SECONDARY EDUCATION, MUSIC, MUSIC ACTIVITIES, MUSIC READING, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, MUSIC THEORY, INSTRUMENTATION, LISTENING SKILLS, FINE ARTS, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, TEACHING TECHNIQUES, JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS, SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS, CLEVELAND, THIS RESEARCH PRODUCED AID TRIED A SYLLABUS FOR JUNIOR AND SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL GENERAL H,:lSIC CLASSES. THE COURSE IS BASED ON (1) A STUDY OF THE CURRENT STATUS OF SUCH CLASSES AND SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVING THEM,(2) A PARTICULAR AESTHETIC POSITION ABOUT THE NATURE AND VALUE OF MUSIC AND THE MEANS FOR REALIZING MUSIC'S VALUE,(3) RELEVANT PRINCIPLES OF COURSE CONSTRUCTION AND PEDAGOGY FROM THE CURRICULUM REFORM MOVEMENT IN AMERICAN EDUCATION, AND (4) COMBINING THE ABOVE POINTS IN AN ATTEMPT TO SATISFY THE REQUIREMENTS OF PRESENT NEEDS, A CONSISTENT AND WELL-ACCEPTED PHILOSOPHICAL POSITION, AND CURRENT THOUGHT ABOUT EDUCATIONAL STRATEGY. THE MAJOR OBJECTIVE OF THE COURSE IS TO DEVELOP THE ABILITY TO HAVE AESTHETIC EXPERIENCES OF MUSIC. SUCH EXPERIENCES ARE CONSIDERED TO CONTAIN TWO ESSENTIAL BEHAVIORS -- AESTHETIC PERCEPTION AND AESTHETIC REACTION. THE COURSE MATERIALS ARE DESIGNED TO SYSTEMATICALLY IMPROVE THE ABILITY TO PERCEIVE THE AESTHETIC CONTENT OF MUSIC, IN A CONTEXT WHICH ENCOURAGES FEELINGFUL REACTION TO THE PERCEIVED AESTHETIC CONTENT. -

Warren Dosanjh the Music Scene Of

i-spysydincambridge.comi-spysydincambridge.com The Music Scene of 1960s CAMBRIDGE Walking Tour, Venues, Bands, Meeting Places and the People Award Winner 2014 researched and compiled by Warren Dosanjh 6th Edition April 2015 Walking Tours 2009-12 Photos © Mick Brown For information on how to book a fascinating guided walking tour of the 1960s Cambridge music scene, please contact: [email protected] Introduction ambridge developed its own unique music scene during the 1960s. Some local musicians later left and became internationally Cfamous while others, equally talented, chose to remain in the city. This booklet describes the venues, meeting places, the way of life of young people during the 1960s and some of the bands that entertained them. The story is told by Cambridge residents and musicians who were there in those times and are still here today! Contents III Map of City Centre showing positions of venues 1-22 Venues, meeting places and gallery of local people 24-26 Roots of Cambridge Rock photos and links 27 Devi Agarwala remembered and Maxpeed Printers 28-31 Pete Rhodes, Alan Styles, Tony Colleno and Clive Welham remembered 32-67 Bands and Vocalists 68 About this booklet 1 Photo by Ralph Goodfellow Publisher and main contributor: Warren Dosanjh, email: [email protected] Editing/Layout/Selected Youtube clips: Mick Brown, email: [email protected] with editorial help, advice and research by David Chapman Further contributions and research: Lee Wood, Alan Willis, Jenny Spires, Brian Foskett, Viv ‘Twig’ -

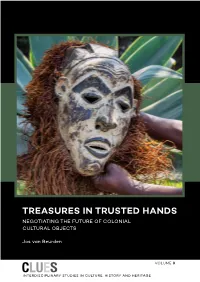

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

The Old Order Changeth': the Aborted Evolution

‗THE OLD ORDER CHANGETH‘: THE ABORTED EVOLUTION OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE, 1917-1931 A Dissertation by SEAN PATRICK KELLY Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams Committee Members, Troy Bickham Rebecca Hartkopf Schloss Anthony Stranges Peter Hugill Head of Department, David Vaught August 2014 Major Subject: History Copyright 2014 Sean Patrick Kelly ABSTRACT In the aftermath of the Great War (1914-18), Britons could, arguably for the first time since 1763, look to the immediate future without worrying about the rise of an anti- British coalition of European states hungry for colonial spoils. Yet the shadow cast by the apparent ease with which the United States rose to global dominance after 1940 has masked the complexity and uncertainty inherent in what turned out to be the last decades of the British Empire. Historians of British international history have long recognised that the 1920s were a period of adjustment to a new world, not simply the precursor to the disastrous (in hindsight) 1930s. As late as the eve of the Second World War, prominent colonial nationalists lamented that the end of Empire remained impossible to foresee. Britons, nevertheless, recognised that the Great War had laid bare the need to modernise the archaic, Victorian-style imperialism denounced by The Times, amongst others. Part I details the attempts to create a ‗New Way of Empire‘ before examining two congruent efforts to integrate Britain‘s self-governing Dominions into the very heart of British political life.