Double-Takes David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Quebec

le cinema quebecois the state of quebec Quebec is at a crossroads, and the deci sions - both federal and provincial - which will be made in the coming months are crucial. Taking stock of the situation of feature filming in the province, Jean-Pierre Tadros traces a sombre portrait. by Jean-Pierre Tadros The election of the Parti Quebecois has created a sort of been given. It remains to be seen whether the government 'before and after' effect, a temptation to evaluate what had can and will take the proper steps to help the industry out come before in order to better measure what is to come of its economic and spiritual depression. Perhaps it is al afterwards. One would like to look back and say that the ready too late. state of cinema in Quebec on November 15 was strong and For the last few years, there's been an uneasy feeling, healthy, that the directors and producers, not to mention the sense of something going wrong. The 'cinema' milieu the technicians, were in good form. Alas! Nothing could be reflected the malaise which ran through Quebec and which, farther from the truth. To be fair, le cinema quebecois finally, brought in the new government. Perhaps it should is still struggling along but its condition has become have been expected that a generation which was brought up critical. The months ahead will tell whether the illness is during the 'quiet revolution' would have grown up thinking terminal. big. Too big! La folic des grandeurs. Quebec's cinema was to pay dearly for trying to embody those dreams. -

A Film by DENYS ARCAND Produced by DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS

ÉRIC MÉLANIE MELANIE MARIE-JOSÉE BRUNEAU THIERRY MERKOSKY CROZE AN EYE FOR BEAUTY A film by DENYS ARCAND Produced by DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS before An Eye for Beauty written and directed by Denys Arcand producers DENISE ROBERT DANIEL LOUIS THEATRICAL RELEASE May 2014 synopsis We spoke of those times, painful and lamented, when passion is the joy and martyrdom of youth. - Chateaubriand, Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb Luc, a talented young architect, lives a peaceful life with his wife Stephanie in the stunning area of Charlevoix. Beautiful house, pretty wife, dinner with friends, golf, tennis, hunting... a perfect life, one might say! One day, he accepts to be a member of an architectural Jury in Toronto. There, he meets Lindsay, a mysterious woman who will turn his life upside down. AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT cast Luc Éric Bruneau Stéphanie Mélanie Thierry Lindsay Melanie Merkosky Isabelle Marie-Josée Croze Nicolas Mathieu Quesnel Roger Michel Forget Mélissa Geneviève Boivin-Roussy Karine Magalie Lépine-Blondeau Museum Director Yves Jacques Juana Juana Acosta Élise Johanne-Marie Tremblay 3 AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT crew Director Denys Arcand Producers Denise Robert Daniel Louis Screenwriter Denys Arcand Director of Photography Nathalie Moliavko-Visotzky Production Designer Patrice Bengle Costumes Marie-Chantale Vaillancourt Editor Isabelle Dedieu Music Pierre-Philippe Côté Sound Creation Marie-Claude Gagné Sound Mario Auclair Simon Brien Louis Gignac 1st Assistant Director Anne Sirois Production manager Michelle Quinn Post-Production Manager Pierre Thériault Canadian Distribution Les Films Séville AN EYE FOR BEAUTY | PRESS KIT 4 SCREENWRITER / DIRECTOR DENYS ARCAND An Academy Award winning director, Denys Arcand's films have won over 100 prestigious awards around the world. -

Francis Mankiewicz

francis mankiewicz to berlin with love by joan irving It is a fight to the finish, but the following interviews with director Francis Mankiewicz, and producers Marcia Couelle and Claude Godbout suggest that they may be winning with their film Les bons debarras (Good Rid dance), selected to represent Canada at the 1980 Berlin Film Festival. Director of Les bons debarras, Francis Mankiewicz with Marie Tifo — pointing the way to Berlin! Cinema Canada/11 really didn't know what to think of it, so 1 of my universe. You might find something The year 1980 marks a revival in just set it aside while I finished the other for yourself in it.' Quebecois films. Following the slump of film. But 1 found that 1 was continually the late-seventies — when directors like thinking of Le bons debarras. There was Cinema Canada: It is surprising how Claude Jutra, Gilles Carle, Francis Man •something in that script that haunted me. much in Les bons debarras resembles kiewicz, and others, left Montreal to work At the time there were a lot of opportu the world you created in Le temps d'une in Toronto— several directors, including nities to work in Toronto. What brought chasse. Carle, Mankiewicz, Jean-Claude Labrec- me back to Quebec was Rejean's script. Francis Mankiewicz: It would be difficult que, Andre Forcier and Jean-Guy Noel for me to direct a film in which I didn't find are now completing new features. First to Cinema Canada: Ducharme has pub something I could feel close to. The be released is Mankiewicz's Les bons de lished several novels, but this was his first resemblance is partly style, but mostly, I barras (Good Riddance). -

Press Kit Falling Angels

Falling Angels A film by Scott Smith Based on the novel by Barbara Gowdy With Miranda Richardson Callum Keith Rennie Katherine Isabelle RT : 101 minutes 1 Short Synopsis It is 1969 and seventeen year old Lou Field and her sisters are ready for change. Tired of enduring kiddie games to humour a Dad desperate for the occasional shred of family normalcy, the Field house is a place where their Mom’s semi-catatonic state is the result of a tragic event years before they were born. But as the autumn unfolds, life is about to take a turn. This is the year that Lou and her sisters are torn between the lure of the world outside and the claustrophobic world of the Field house that can no longer contain the girls’ restless adolescence. A story of a calamitous family trying to function, Falling Angels is a story populated by beautiful youthful rebels and ill-equipped parents coping with the draw of a world in turmoil beyond the boundaries of home and a manicured lawn. 2 Long Synopsis Treading the fine line between adolescence and adulthood, the Field sisters have all but declared war on their domineering father. Though Jim Field (Genie and Gemini winner Callum Keith Rennie ) runs the family house like a military camp, it’s the three teenaged daughters who really run the show and baby-sit their fragile mother Mary, (Two-time Oscar ® nominee Miranda Richardson) as she quietly sits on the couch and quells her anxiety with whiskey. It’s 1969 and beneath suburbia’s veneer of manicured lawns and rows of bungalows, the world faces explosive social change. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Armed Robber Strikes Bank the Ganges Branch of Er Service Line and Pulled As of 1:30 P.M

Election special page A11 Gulf Islands Real Estate Inside $ 25 Your Community Newspaper Since 1960 1 (incl. GST) Wednesday, June 23, 2004 44th year Gulf Islands Issue 25 328 Lower Ganges Road, Salt Spring Island, B.C. V8K 2V3 Tel: 250-537-9933 Fax: 250-537-2613 Toll-free: 1-877-537-9934 e-mail: [email protected] editorial: [email protected] Website: www.gulfislands.net THIS WEEK’S INSERTS • Ganges • Ganges Village Pharmasave Market • Mouat’s Home • Thrifty Foods Hardware • Slegg Lumber Armed robber strikes bank The Ganges branch of er service line and pulled as of 1:30 p.m. Tuesday, tion will continue using the dog-handling personnel to the Bank of Montreal was open cash drawers and stole his direction of travel was video evidence and possible Salt Spring. robbed Tuesday morning by money,” said Giles. “He was unknown. fingerprint evidence that is Pender RCMP happened �������������������� an armed, masked man. carrying what appeared to be Because the man was potentially available at the to be on the island and took Salt Spring RCMP Sgt. a rifle under one arm.” wearing a mask, an accurate site.” care of boat searches in Gan- �������� Mike Giles said police Two customer service rep- description was difficult to RCMP contacted ferry ges Harbour. responded to the call at resentatives were working at obtain, said Giles, beyond personnel, requested assis- Anyone with any infor- 11:39. the time and the man took the fact the robber was of tance of Duncan and Sid- mation about this incident “A man dressed in dark funds from both drawers. -

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing?

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing? By Chairman of the U.S. based Romanian National Vanguard©2007 www.ronatvan.com v. 1.6 1 INDEX 1. Are Jews satanic? 1.1 What The Talmud Rules About Christians 1.2 Foes Destroyed During the Purim Feast 1.3 The Shocking "Kol Nidre" Oath 1.4 The Bar Mitzvah - A Pledge to The Jewish Race 1.5 Jewish Genocide over Armenian People 1.6 The Satanic Bible 1.7 Other Examples 2. Are Jews the “Chosen People” or the real “Israel”? 2.1 Who are the “Chosen People”? 2.2 God & Jesus quotes about race mixing and globalization 3. Are they “eternally persecuted people”? 3.1 Crypto-Judaism 4. Is Judeo-Christianity a healthy “alliance”? 4.1 The “Jesus was a Jew” Hoax 4.2 The "Judeo - Christian" Hoax 4.3 Judaism's Secret Book - The Talmud 5. Are Christian sects Jewish creations? Are they affecting Christianity? 5.1 Biblical Quotes about the sects , the Jews and about the results of them working together. 6. “Anti-Semitism” shield & weapon is making Jews, Gods! 7. Is the “Holocaust” a dirty Jewish LIE? 7.1 The Famous 66 Questions & Answers about the Holocaust 8. Jews control “Anti-Hate”, “Human Rights” & Degraded organizations??? 8.1 Just a small part of the full list: CULTURAL/ETHNIC 8.2 "HATE", GENOCIDE, ETC. 8.3 POLITICS 8.4 WOMEN/FAMILY/SEX/GENDER ISSUES 8.5 LAW, RIGHTS GROUPS 8.6 UNIONS, OCCUPATION ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMIA, ETC. 2 8.7 IMMIGRATION 9. Money Collecting, Israel Aids, Kosher Tax and other Money Related Methods 9.1 Forced payment 9.2 Israel “Aids” 9.3 Kosher Taxes 9.4 Other ways for Jews to make money 10. -

Productions in Ontario 2006

2006 PRODUCTION IN ONTARIO with assistance from Ontario Media Development Corporation www.omdc.on.ca You belong here FEATURE FILMS – THEATRICAL ANIMAL 2 AWAY FROM HER Company: DGP Animal Productions Inc. Company: Pulling Focus Pictures ALL HAT Producers: Lewin Webb, Kate Harrison, Producer: Danny Iron, Simone Urdl, Company: No Cattle Productions Inc./ Wayne Thompson, Jennifer Weiss New Real Films David Mitchell, Erin Berry Director: Sarah Polley Producer: Jennifer Jonas Director: Ryan Combs Writers: Sarah Polley, Alice Munro Director: Leonard Farlinger Writer: Jacob Adams Production Manager: Ted Miller Writer: Brad Smith Production Manager: Dallas Dyer Production Designer: Kathleen Climie Line Producer/Production Manager: Production Designer: Andrew Berry Director of Photography: Luc Montpellier Avi Federgreen Director of Photography: Brendan Steacy Key Cast: Gordon Pinsent, Julie Christie, Production Designer: Matthew Davies Key Cast: Ving Rhames, K.C. Collins Olympia Dukakis Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Shooting Dates: November – December 2006 Shooting Dates: February – April 2006 Key Cast: Luke Kirby, Rachael Leigh Cook, Lisa Ray A RAISIN IN THE SUN BLAZE Shooting Dates: October – November 2006 Company: ABC Television/Cliffwood Company: Barefoot Films GMBH Productions Producers: Til Schweiger, Shannon Mildon AMERICAN PIE PRESENTS: Producer: John Eckert Executive Producer: Tom Zickler THE NAKED MILE Executive Producers: Craig Zadan, Neil Meron Director: Reto Salimbeni Company: Universal Pictures Director: Kenny Leon Writer: Reto Salimbeni Producer: W.K. Border Writers: Lorraine Hansberry, Paris Qualles Line Producer/Production Manager: Director: Joe Nussbaum Production Manager: John Eckert Lena Cordina Writers: Adam Herz, Erik Lindsay Production Designer: Karen Bromley Production Designer: Matthew Davies Line Producer/Production Manager: Director of Photography: Ivan Strasburg Director of Photography: Paul Sarossy Byron Martin Key Cast: Sean Patrick Thomas, Key Cast: Til Schweiger Production Designer: Gordon Barnes Sean ‘P. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Download This PDF File

CINEMA C A N_A D A BY JIM LEVESQUE he following isa list of current prolects being produced in series will be adapted from popular Stoker, Barbara Ann Schoemaker art Nov.2nd. p. Serge Bany d. Stephane On Location Canadian stories and books. exec. p. d. Lawrence Pevec cast. Michelle Bertin p. co-ord. Nicole Hilareguy Canada. Only TV series and films of one hour or longer are Michael MacMillan. Peter Sussman Allen I. p. Johnny Depp, Holly p.sec. Johanne Messier. included. Projects are separated into four categories: ON 3 THEMES - SUSPENSE INC. exec. In charge of p. Nada Harcourt Robinson. Peter Deluise, Dustin THE LITTLE FLYING BEARS T (5 14 ) 874-1641 /95 4-4370 sup. p. Seaton McLean p. mgr. John Nguyen, Sieve Williams (26 x 1/2 hr.) animated series. A LOCATION , PREPRODUCTION , IN NEGOTIATION, and IN THE POUR CENT MILLIONS Calvert d. Brad Turner. various lop . BOOKER co-production with Zagreb Film CAN . While the status of projects are subject to change ,onl ythose Fourth tslefilm of a , 6 x 90 min, Torquil Campbell. Yannick Bisson. TV series. Shooting began July 21st (Yugoslavia ). To be aired early 1990. suspense series· ( Haute Samantha Follows pub. Jeremy Katz and continues until Oec. 14th. p. p. Jacques Pettigrew, Andre Lamy. in activepreproduction at the time of publication -those which have Tension/Super Polar). A co-production TOM ALONE Brooke Kennedy p. mgr. Michelle Bogdan Zizic del. p. Andre Belanger d. set adate for principal photographyand are also engaged in casting with Hamster Productions ( France). (2 x I hr.) television adventure/drama. -

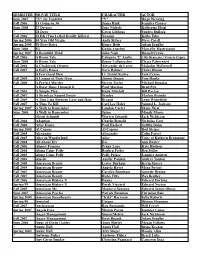

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont