GODS IDENTITY According to Ancient Heb Scholars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(S): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(s): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 385-408 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3260509 . Accessed: 11/05/2013 22:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.207.2.50 on Sat, 11 May 2013 22:44:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JBL 105/3 (1986) 385-408 ASHERAH IN THE HEBREW BIBLE AND NORTHWEST SEMITIC LITERATURE* JOHN DAY Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, England, OX2 6QA The late lamented Mitchell Dahood was noted for the use he made of the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts in the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. Although many of his views are open to question, it is indisputable that the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts have revolutionized our understanding of the Bible. One matter in which this is certainly the case is the subject of this paper, Asherah.' Until the discovery of the Ugaritic texts in 1929 and subsequent years it was common for scholars to deny the very existence of the goddess Asherah, whether in or outside the Bible, and many of those who did accept her existence wrongly equated her with Astarte. -

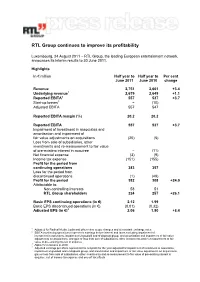

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

The Relationship of Yahweh and El: a Study of Two Cults and Their Related Mythology

Wyatt, Nicolas (1976) The relationship of Yahweh and El: a study of two cults and their related mythology. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2160/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] .. ýýý,. The relationship of Yahweh and Ell. a study of two cults and their related mythology. Nicolas Wyatt ý; ý. A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy rin the " ®artänont of Ssbrwr and Semitic languages in the University of Glasgow. October 1976. ý ý . u.: ý. _, ý 1 I 'Preface .. tee.. This thesis is the result of work done in the Department of Hebrew and ': eraitia Langusgee, under the supervision of Professor John rdacdonald, during the period 1970-1976. No and part of It was done in collaboration, the views expressed are entirely my own. r. .e I should like to express my thanks to the followings Professor John Macdonald, for his assistance and encouragement; Dr. John Frye of the Univeritty`of the"Witwatersrandy who read parts of the thesis and offered comments and criticism; in and to my wife, whose task was hardest of all, that she typed the thesis, coping with the peculiarities of both my style and my handwriting. -

THE SUPREMACY of BA'al OVER MOT in UGARITIC CYCLE of COSMOGONIC MYTHS and ITS INFLUENCE on the OLD TESTAMENT Interprets the Bi

AJBT. Volume 21(6). February 9, 2020 THE SUPREMACY OF BA‘AL OVER MOT IN UGARITIC CYCLE OF COSMOGONIC MYTHS AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE OLD TESTAMENT Abstract The supremacy of Ba‘al over Mot in Ugaritic Cycle of Cosmogonic Myths was a prominent tradition within the world of the ancient Near East. This custom projects Ba‘al as the god of fertility and rain, but Mot as that of death and underworld. Since the world of the time was agrarian, most of the peoples involved in the worship of Ba‘al for bumper harvests but cast aspersion on Mot. The paper, therefore, claims that the incessant drifting away by ancient Israel from Yahweh for the worship of Ba‘al was on account of this cultural influence from the surrounding nations. The paper employed the canonical approach which interprets the biblical text in its canonical context, to analyse the influence of this type in the OT setting. In this direction, the writer examined ancient Ugarit from the perspective of archaeology. The paper also considered lexical analyses of the concepts of “Ba‘al” and “Mot” from the general worldview of the ancient world, especially within the cultural understanding of the people of Israel. The basis of this analysis was to identify possible supremacy of Ba‘al over Mot, the god of the dead. The writer finally investigated the possible areas of influence and the paper identified the following elements, namely, naming off some towns and cities after Ba‘al within the geographical locations of ancient Israel, worship of Ba‘al beginning from Israel’s contact with the Moabites in the wilderness and throughout the Judges and prevalence of Ba‘al worship during the United Kingdom and the time of Monarchy. -

Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-13-2017 Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation White, James Jefferson. "Jewish Culture in the Christian World." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James J White Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Sarah Davis-Secord, Chairperson Timothy Graham Michael Ryan i JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD by JAMES J WHITE PREVIOUS DEGREES BACHELORS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD BY James White B.S., History, University of North Texas, 2013 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2017 ABSTRACT Christians constantly borrowed the culture of their Jewish neighbors and adapted it to Christianity. This adoption and appropriation of Jewish culture can be fit into three phases. The first phase regarded Jewish religion and philosophy. From the eighth century to the thirteenth century, Christians borrowed Jewish religious exegesis and beliefs in order to expand their own understanding of Christian religious texts. -

THE DESTINY of the WORLD : a STUDY on the END of the UNIVERSE in the Llght of ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEXTS

THE DESTINY OF THE WORLD : A STUDY ON THE END OF THE UNIVERSE IN THE LlGHT OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TEXTS Sherine M. ElSebaie A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto O Copyright by Sherine M. ElSebaie (2000) National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KfA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. The Destiny of The World: A Study on the End of The Universe in The Light of Ancient Egyptian Texts Sherine M. ElSebaie Master of Arts, 2000 Dept. of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis is a theme that has not been fully çtudied until today and that has long been thought to be overlooked by the ancient Egyptians in a negative way. -

You Will Be Like the Gods”: the Conceptualization of Deity in the Hebrew Bible in Cognitive Perspective

“YOU WILL BE LIKE THE GODS”: THE CONCEPTUALIZATION OF DEITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE IN COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE by Daniel O. McClellan A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Craig Broyles, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Martin Abegg, PhD; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY December, 2013 © Daniel O. McClellan Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 1.1 Summary and Outline 1 1.2 Cognitive Linguistics 3 1.2.1 Profiles and Bases 8 1.2.2 Domains and Matrices 10 1.2.3 Prototype Theory 13 1.2.4 Metaphor 16 1.3 Cognitive Linguistics in Biblical Studies 19 1.3.1 Introduction 19 1.3.2 Conceptualizing Words for “God” within the Pentateuch 21 1.4 The Method and Goals of This Study 23 Chapter 2 – Cognitive Origins of Deity Concepts 30 2.1 Intuitive Conceptualizations of Deity 31 2.1.1 Anthropomorphism 32 2.1.2 Agency Detection 34 2.1.3 The Next Step 36 2.2. Universal Image-Schemas 38 2.2.1 The UP-DOWN Image-Schema 39 2.2.2 The CENTER-PERIPHERY Image-Schema 42 2.3 Lexical Considerations 48 48 אלהים 2.3.1 56 אל 2.3.2 60 אלוה 2.3.3 2.4 Summary 61 Chapter 3 – The Conceptualization of YHWH 62 3.1 The Portrayals of Deity in the Patriarchal and Exodus Traditions 64 3.1.1 The Portrayal of the God of the Patriarchs -

'ONE' in EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That We May Speak Of

MONO-, PAN-, AND COSMOTHEISM: THINKING THE 'ONE' IN EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That we may speak of Egyptian 'theology' is everything but self-evident. Theology is not something to be expected in every religion, not even in the Old Testament. In Germany and perhaps also elsewhere, there is a heated debate going on in OT studies about whether the subject of the discipline should be defined in the traditional way as "theology of OT" or rather, "history of Israelite religion".(1) The concern with questions of theology, some people argue, is typical only of Early Christianity when self-definitions and clear-cut concepts were needed in order to keep clear of Judaism, Gnosticism and all kinds of sects and heresies in between. Theology is a historical and rather exceptional phenomenon that must not be generalized and thoughtlessly projected onto other religions.(2) If theology is a contested notion even with respect to the OT, how much more so should this term be avoided with regard to ancient Egypt! The aim of my lecture is to show that this is not to be regarded as the last word about ancient Egyptian religion but that, on the contrary, we are perfectly justified in speaking of Egyptian theology. This seemingly paradoxical fact is due to one single exceptional person or event, namely to Akhanyati/Akhenaten and his religious revolution. Before I deal with this event, however, I would like to start with some general reflections about the concept of 'theology' and the historical conditions for the emergence and development of phenomena that might be subsumed under that term. -

“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

“Temple of my Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshi Community Aditya N. Bhattacharjee School of Religious Studies McGill University Montréal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2017 © 2017 Aditya Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee 2 Abstract In this thesis, I offer new insight into the Hindu Bangladeshi community of Montreal, Quebec, and its relationship to community religious space. The thesis centers on the role of the Montreal Sanatan Dharma Temple (MSDT), formally inaugurated in 2014, as a community locus for Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshis. I contend that owning temple space is deeply tied to the community’s mission to preserve what its leaders term “cultural authenticity” while at the same time allowing this emerging community to emplace itself in innovative ways in Canada. I document how the acquisition of community space in Montreal has emerged as a central strategy to emplace and renew Hindu Bangladeshi culture in Canada. Paradoxically, the creation of a distinct Hindu Bangladeshi temple and the ‘traditional’ rites enacted there promote the integration and belonging of Bangladeshi Hindus in Canada. The relationship of Hindu- Bangladeshi migrants to community religious space offers useful insight on a contemporary vision of Hindu authenticity in a transnational context. Bhattacharjee 3 Résumé Dans cette thèse, je présente un aperçu de la communauté hindoue bangladaise de Montréal, au Québec, et surtout sa relation avec l'espace religieux communautaire. La thèse s'appuie sur le rôle du temple Sanatan Dharma de Montréal (MSDT), inauguré officiellement en 2014, en tant que point focal communautaire pour les Bangladeshis hindous de Montréal. -

Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 1

BTE • Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 1 Ancient Thunder Study Guide In this study guide you will find all kinds of information to help you learn more about the myths that inspired BTE's original play Ancient Thunder, and about Ancient Greece and its infleunce on culture down to the present time. What is Mythology? ...................................................2 The stories the actors tell in Ancient Thunder are called myths. Learn what myths are and how they are associated with world cultures. When and where was Ancient Greece? ..................... 10 The myths in Ancient Thunder were created thousands of years ago by people who spoke Greek. Learn about where and when Ancient Greece was. What was Greek Art like? ..........................................12 Learn about what Greek art looked like and how it inspired artists who came after them. How did the Greeks make Theatre? .......................... 16 The ancient Greeks invented a form of theatre that has influenced storytelling for over two thousand years. Learn about what Greek theatre was like. What was Greek Music like? ..................................... 18 Music, chant, and song were important to Greek theatre and culture. Learn about how the Greeks made music. What are the Myths in Ancient Thunder? ................. 20 Learn more about the Greek stories that are told in Ancient Thunder. Actvities ........................................................................................................... 22 Sources ..............................................................................................................24 Meet the Cast .................................................................................................... 25 2 BTE • Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 What is Mythology? Myths are stories that people tell to explain and understand how things came to be and how the world works. The word myth comes from a Greek word that means story. Mythology is the study of myths. -

Table of Contents

Table of ConTenTs Introduction Phi Sigma Kappa .........................................41 Office of Greek Life ....................................... 2 Pi Beta Phi ..................................................42 Questions & Answers. ..................................... 3 Pi Kappa Alpha ............................................43 Greek Life at FSU ......................................... 4 Pi Kappa Phi ...............................................44 University Policies ......................................... 5 Pi Lambda Phi .............................................45 Sigma Alpha Epsilon ....................................46 Greek organizations Sigma Beta Rho ...........................................47 Alpha Chi Omega ........................................... 6 Sigma Chi ....................................................48 Alpha Delta Phi ............................................. 7 Sigma Delta Tau ...........................................49 Alpha Delta Pi .............................................. 8 Sigma Gamma Rho .......................................50 Alpha Epsilon Pi ........................................... 9 Sigma Iota Alpha .........................................51 Alpha Gamma Delta ......................................10 Sigma Lambda Beta .....................................52 Alpha Kappa Alpha .......................................11 Sigma Nu ....................................................53 alpha Kappa Delta Phi ..................................12 Sigma Phi Epsilon ........................................54 -

By Larry and June Acheson Several Years Ago, on a Popular Television

Several years ago, on a popular television program entitled Dragnet, a very austere voice would advise all viewers, “The story you are about to see is true. The names have been changed to protect the innocent.” This show was a drama depicting the everyday challenges faced by two police officers working their beat in Los Angeles, California. Why were the names of innocent people changed for this program? Why didn’t they provide viewers the actual names of each person involved? We know why. A name identifies who a person is. When a crime is perpetrated, the first question on everyone’s mind is, “Who did it?”, or as the popular expression goes, “Whodunnit?” We all want to know who the guilty party is so he can be identified, then apprehended so he can “get his due.” But what if the police arrest the wrong guy? What if the media then plasters his name everywhere for all to see? How would you like to be falsely accused and have everyone believe that you’re a criminal, while all along you are completely innocent? Or how would you like it if a hardened criminal learns that you are the person who tipped the police off about a crime that he committed, and he learned your name by watching Dragnet from the comforts of his cell? How would you feel, knowing that in a few months this man will be up for parole? Would you feel safe? But let’s examine this name-changing game from the reverse angle. Suppose you had saved someone’s life or had done some other deed worthy of recognition.