“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

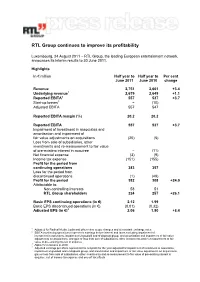

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

Akshay Moorti Art

+91-8048859584 Akshay Moorti Art https://www.indiamart.com/akshaymoortiart/ Established as a Proprietor firm in the year 1991, we “Akshay Moorti Art” are a leading Manufacturer of a wide range of Ram Darbar Statues, Decorative Statue, Bani Thani Statues, etc. About Us Established as a Proprietor firm in the year 1991, we “Akshay Moorti Art” are a leading Manufacturer of a wide range of Ram Darbar Statues, Decorative Statue, Bani Thani Statues, etc. Situated in Jaipur (Rajasthan, India), we have constructed a wide and well functional infrastructural unit that plays an important role in the growth of our company. We offer these products at reasonable rates and deliver these within the promised time-frame. Under the headship of “Mr. Hemant Sharma” (Manager), we have gained a huge clientele across the nation. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/akshaymoortiart/profile.html RADHA KRISHNA STATUE O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Marble Radha Krishna Statue Radha Krishna Goddess Marble Statue Marble Radha Krishna Statue Marble Radha Krishna Statue KALI MATA STATUE O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Marble Kali Mata Statue Marble Shera Wali Mata Statue Marble Kali Mata Statue Kali Statue MARBLE STATUE O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Marble Bhim Rao Ambedkar Marble Gandhi Ji Statue Statue White Marble Statues Marble Santoshi Mata Statue RAM DARBAR STATUES O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Marble Ram Darbar Statue Ram Darbar Statue 2 Feet Lord Rama Darbar 1 Feet Marble Ram Darbar Statue Statue BHERU BABA STATUE O u r P r o d u c t R a -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

Dixit Art Sculpturals

+91-8048417510 Dixit Art Sculpturals https://www.indiamart.com/dixitartsculpturals/ Dixit Art Sculpturals “DAS” was Established in the year 1978, is regarded amongst the premier Manufacturers, Suppliers, Wholesaler and Retailer of an elaborate range of Marble Murties and Statues. About Us "Building Long Lasting Relations with our Customers and Provide them with best quality work at reasonable prices and enhance their satisfaction". Dixit Art Sculpturals “DAS” was Established in the year 1978, is regarded amongst the premier manufacturers, suppliers, wholesaler and retailer of an elaborate range of Marble Murties and Statues. We have a wide and well functional infrastructural unit at Jaipur, Rajasthan India and which helps us in carving and designing a remarkable collection of Marble statues as per the Customer’s Requirements. “DAS” was established by Mr. Sitaram Dixit with lot of efforts, hard-work and enthusiasm Now our firm is running under the leadership and direction of Mr. Hemant Dixit and Mr. Kapil Dixit. They benefit the organization with immeasurable knowledge and experiences gained over the years and help us maintain the creditability of our enterprise. We are manufacturers, suppliers, wholesaler, retailer and trader of marble Murties, idols, statues and other customized marble based products. Our statues are an amalgamation of rich traditional & modern art, and this enthralling range will add to the divine and aesthetic beauty of temples, homes, offices, hotels and other establishments. We have our expertise in God and Goddess -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 6, Issue 4 October 2012 Hari OM

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 6, Issue 4 October 2012 Hari OM Lord Ganesha is worshipped before one begins anything new in life. He is also called Vigneshwara, the word “Vigna” means “obstacles” and he is the lord for removing obstacles. The birth of Lord Ganesha is celebrated as Vinayaka Chavithi. Using turmeric paste, Goddess Parvathi created Lord Ganesha as her loyal son and protector. Lord Shiva, not knowing the truth got furious with Lord Ganesha when he was not let to enter his own house. Furious Lord Shiva lost his patience and severed Lord Ganesha’s head killing him instantly. When Goddess Parvathi heard of this, she threatened to destroy the entire creation. Lord Shiva understood what had happened, ordered Lord Brahma to get the head of first animal he encounters facing north. Lord Brahma returned with the head of a powerful elephant. Lord Shiva placed it on Lord Ganesha, breathed new life into him and announced him as his son as well. He also declared Lord Ganesha to be the foremost of all gods and leader of all ganas (being of life) and hence the name ‘Ganapathi’. This year Diwali Mahalakhsmi Vinayaka Chavithi was observed on 19th of September. Devotees all over the world get Lord Ganesha’s idol made out of clay, perform puja and offer Lord Ganesha’s favorite Blessedness, eternal peace, Arising from perfect modak as prasadam. On the day of Ananta Chaturdasi, they freedom, is the highest conception of religion immerse Lord Ganesha into water. Lord Ganesha’s idol in underlying all the ideas of God in Vedanta absolutely our Balaji Temple arrived and installation was done on this free existence, not bound by anything, no change, no nature, nothing that can produce a change in Him. -

Saran Santas

Santas Saran Santas (see Sandan) Sapas Canaanite Buih, who came, like Aphrodite, from santer North American [Saps.Shapash:=Babylonian Samas: the sea. a fabulous animal =Sumerian Utu] Sar (see Shar) Santeria African a sun-god sara1 Buddhist a god of the Yoruba In some accounts, Sapas is female. an arrow used in rites designed to Santi Hindu Saphon (see Mount Zaphon) ward off evil spirits (see also capa) a goddess Sapling (see Djuskaha.Ioskeha) Sara2 Mesopotamian consort of Tivikrama Saps (see Sapas) a war god, Babylonian and Sumerian Santiago South American Sapta-Loka Hindu son of Inanna, some say a later version of Ilyapa derived from the 7 realms of the universe Sara-mama (see Saramama) the Spanish St James In some versions, the universe has Saracura South American Santoshi Mata Hindu three realms (Tri-Loka). In the version a water-hen a mother-goddess that postulates seven, Sapta-Loka, they When Anatiwa caused the flood, this Sanu1 Afghan are listed as: bird saved the ancestors of the tribes by [Sanru] 1. Bhur-Loka, the earth carrying earth to build up the mountain- a Kafir god 2. Bhuvar-Loka, the home of the sage top on which the survivors stood. father of Sanju in the sky Sarada Devi1 Hindu Sanu2 (see Sanju) 3. Jona-Loka, the home of wife of Ramakrishna Sanugi Japanese Brahma’s children Sarada Devi2 Tibetan a bamboo-cutter 4. Marar-Loka, the home of the saints a Buddhist-Lamaist fertility-goddess He found the tiny Kaguya in the heart 5. Satya-Loka, the home of the gods and goddess of autumn and of a reed and reared her. -

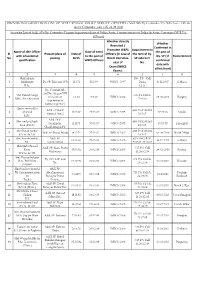

Gradation List of WBPS Officers 2019.Xlsx

PROVISIONAL GRADATION LIST OF WEST BENGAL POLICE SERVICE OFFICERS (Addl. SPs/Dy.Commdts./ Dy. S.Ps/Asstt. CPs & Asstt. Commdts. ) AS ON 01-05-2019 Seniority List of Addl. SPs/Dy. Commdts./Deputy Superintendents of Police/Asstt. Commissioners of Police & Asstt. Commdts.(W.B.P.S. Officers) Whether directly Whether Recruited / Confirmed in Promotee WBPS Appointment in Name of tlhe Officer Date of entry the post of Sl. Present place of Date of Officers (In case of the rank of Dy. with educational to the post of Dy. SP ( If Home District No. posting Birth Direct Recruitee SP vide G.O. qualification WBPS Officers confirmed year of No. date with Exam.(WBCS effect from) Exam.) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shri Jayanta 138 - P.S. - Cell 1 Mukherjee Dy. SP, Telecom, WB 3.12.72 15.2.99 WBCS - 1997 Dated 14.12.2007 Kolkata B.Sc. 3.2.99. Dy. Commdt. IR. 2nd Bn., Siliguri WB Shri Rakesh Singh 956-P.S.Cell dt. 2 (to work on 5.5.72 8.8.06 WBCS-2004 08.08.2008 Hooghly MSC, Bio Chemistry 29.6.06 deputation to Kalimpong Dist.) Quazi Samsuddin Addl. SP.Rural 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 3 Ahamed 11.03.77 27.03.07 WBCS-2005 27.03.09 Malda Howrah Rural 20.3.07. M.Sc. Addl. DCP. Shri Amlan Ghosh 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 4 Serampore, 11.11.73 30.03.07 WBCS-2005 30.03.09 Jalpaiguri M.A.(Part I) 20.3.07. Chandannagar PC Shri Dipak Sarkar 488-P.S.Cell dtd. -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Restaurant Name Address City Name 56 Bhog F 1 & 2, Siddhraj Zavod

Restaurant Name Address City Name 56 Bhog F 1 & 2, Siddhraj Zavod, Sargasan Cross Road, SG Highway, Gandhinagar, North Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad El Dorado Hotel, Across Crossword, Mithakhali Six Roads, Opposite Shree Krishna Complex, Navrangpura, Aureate - El Dorado Hotel Ahmedabad Central Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad-380009 Armoise Hotel, Ground Floor, Off CG Road, Opposite Nirman Bhavan, Navrangpura, Central Ahmedabad, Autograph - Armoise Hotel Ahmedabad Ahmedabad-380009 Beans & Leaves - Hotel Platinum Inn Hotel Platinum Inn, Anjali Cross Roads, Beside Gujarat Gram Haat, Vasna, West Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Bella - Crowne Plaza Crowne Plaza, Shapath 5, SG Road, Near Business Matrix, Satellite, West Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad 1-2, Ground Floor, Ridhi Siddhi Complex, University Road, Opposite Passport Office, Gulbai Tekra, West Blue Spot Cafe Ahmedabad Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad-380009 Regenta Hotel, 15, Ground Floor, Ashram Road, In Regenta Hotel, Usmanpura, Central Ahmedabad, Cafe 15A - Regenta Hotel Ahmedabad Ahmedabad-380013 Whistling Meadows Resort & Lawns, Modi Shikshan Sankool Lane, Off SG Highway, Opposite Nirma Capsicum Restaurant Ahmedabad University, Gota, North Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad-382481 Lemon Tree Hotel, 434/1, Ground Floor, Mithakali Six Cross Roads, In Lemon Tree Hotel, Navrangpura, Citrus Cafe Ahmedabad Central Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad-380006 Aloft Hotel, 1st Floor, Sarkhej Gandhinagar Road, Near Sola Police Station, Sola, North Ahmedabad, Dot Yum - Aloft Hotel Ahmedabad Ahmedabad-380061 Narayani Hotels & Resort, Narayani -

Minutes of 32Nd Meeting of the Cultural

1 F.No. 9-1/2016-S&F Government of India Ministry of Culture **** Puratatav Bhavan, 2nd Floor ‘D’ Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi-110023 Dated: 30.11.2016 MINUTES OF 32nd MEETING OF CULTURAL FUNCTIONS AND PRODUCTION GRANT SCHEME (CFPGS) HELD ON 7TH AND 8TH MAY, 2016 (INDIVIDUALS CAPACITY) and 26TH TO 28TH AUGUST, 2016 AT NCZCC, ALLAHABAD Under CFPGS Scheme Financial Assistance is given to ‘Not-for-Profit’ Organisations, NGOs includ ing Soc iet ies, T rust, Univ ersit ies and Ind iv id ua ls for ho ld ing Conferences, Seminar, Workshops, Festivals, Exhibitions, Production of Dance, Drama-Theatre, Music and undertaking small research projects etc. on any art forms/important cultural matters relating to different aspects of Indian Culture. The quantum of assistance is restricted to 75% of the project cost subject to maximum of Rs. 5 Lakhs per project as recommend by the Expert Committee. In exceptional circumstances Financial Assistance may be given upto Rs. 20 Lakhs with the approval of Hon’ble Minister of Culture. CASE – I: 1. A meeting of CFPGS was held on 7 th and 8th May, 2016 under the Chairmanship of Shri K. K. Mittal, Additional Secretary to consider the individual proposals for financial assistance by the Expert Committee. 2. The Expert Committee meeting was attended by the following:- (i) Shri K.K. Mittal, Additional Secretary, Chairman (ii) Shri M.L. Srivastava, Joint Secretary, Member (iii) Shri G.K. Bansal, Director, NCZCC, Allahabad, Member (iv ) Dr. Om Prakash Bharti, Director, EZCC, Kolkata, Member, (v) Dr. Sajith E.N., Director, SZCC, Thanjavur, Member (v i) Shri Babu Rajan, DS , Sahitya Akademi , Member (v ii) Shri Santanu Bose, Dean, NSD, Member (viii) Shri Rajesh Sharma, Supervisor, LKA, Member (ix ) Shri Pradeep Kumar, Director, MOC, Member- Secretary 3. -

Hindus in South Asia & the Diaspora: a Survey of Human Rights 2007

Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007 www.HAFsite.org May 19, 2008 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1) “Religious persecution may shield itself under the guise of a mistaken and over-zealous piety” (Edmund Burke, February 17, 1788) Endorsements of the Hindu American Foundation's 3rd Annual Report “Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2006” I would like to commend the Hindu American Foundation for publishing this critical report, which demonstrates how much work must be done in combating human rights violations against Hindus worldwide. By bringing these abuses into the light of day, the Hindu American Foundation is leading the fight for international policies that promote tolerance and understanding of Hindu beliefs and bring an end to religious persecution. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) Freedom of religion and expression are two of the most fundamental human rights. As the founder and former co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on India, I commend the important work that the Hindu American Foundation does to help end the campaign of violence against Hindus in South Asia. The 2006 human rights report of the Hindu American Foundation is a valuable resource that helps to raise global awareness of these abuses while also identifying the key areas that need our attention. Congressman Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ) Several years ago in testimony to Congress regarding Religious Freedom in Saudi Arabia, I called for adding Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists to oppressed religious groups who are banned from practicing their religious and cultural rights in Saudi Arabia.