Considering the Deep Sea As a Source of Minerals and Rare Elements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deep Sea Mining on the Horizon?

May 2014 Home Subscribe Archive Contact Thematic focus: Environmental governance, Resource efficiency Wealth in the Oceans: Deep sea mining on the horizon? 2 The deep ocean, the largest biome on Earth at over 1 000 metres below the surface of the ocean, holds vast quantities of untapped energy resources, precious metals and minerals. Advancements in technology have enabled greater access to these treasures. As a result, deep sea mining is becoming increasingly possible. To date no commercial deep sea mining operation has taken place, but plans to open a deep sea mine have recently been announced. Our ability to anticipate the impacts of mining is limited by the lack of knowledge about deep sea biodiversity, ecosystem complexity, and the extent of environmental BYCC NC and social impacts from mining operations. As such, it is important that policies guiding mineral extraction from the deep seas are rooted into adaptive management – allowing for the integration of new scientific information alongside advances in technology. Governance mechanisms for international waters and the seabed need to be strengthened. The tanley Zimny/Flickr/ precautionary approach should be used to avoid repeating instances of S well-known destructive practices associated with conventional mining. Why is this issue important? Minerals and the metals they contain are an essential component of the modern high-tech world. As global stocks of raw mineral resources continue to dwindle due to increasing material consumption, intense demand for valuable metals has pushed up global prices. The result is that manufacturing industries are now seeking access to previously unattainable mineral deposits in the ocean depths. -

Deep-Sea Mining: the Basics

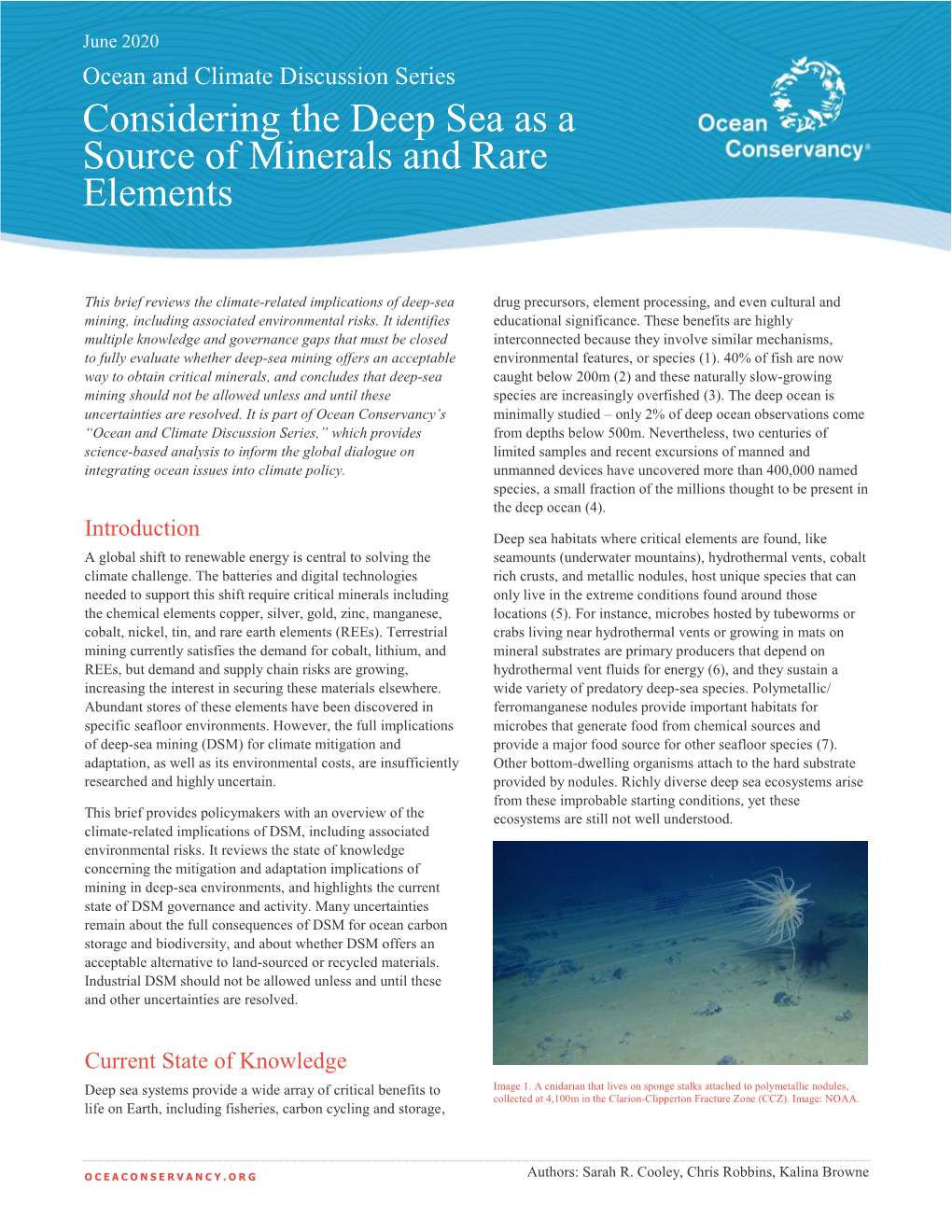

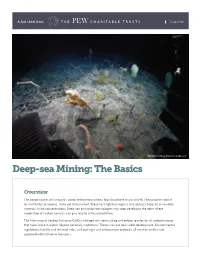

A fact sheet from June 2018 NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Deep-sea Mining: The Basics Overview The deepest parts of the world’s ocean feature ecosystems found nowhere else on Earth. They provide habitat for multitudes of species, many yet to be named. These vast, lightless regions also possess deposits of valuable minerals in rich concentrations. Deep-sea extraction technologies may soon develop to the point where exploration of seabed minerals can give way to active exploitation. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is charged with formulating and enforcing rules for all seabed mining that takes place in waters beyond national jurisdictions. These rules are now under development. Environmental regulations, liability and financial rules, and oversight and enforcement protocols all must be written and approved within three to five years. Figure 1 Types of Deep-sea Mining Production support vessel Return pipe Riser pipe Cobalt Seafloor massive Polymetallic crusts sulfides nodules Subsurface plumes 800-2,500 from return water meters deep Deposition 1,000-4,000 meters deep 4,000-6,500 meters deep Cobalt-rich Localized plumes Seabed pump Ferromanganeseferromanganese from cutting crusts Seafloor production tool Nodule deposit Massive sulfide deposit Sediment Source: New Zealand Environment Guide © 2018 The Pew Charitable Trusts 2 The legal foundations • The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Also known as the Law of the Sea Treaty, UNCLOS is the constitutional document governing mineral exploitation on the roughly 60 percent of the world seabed that lies beyond national jurisdictions. UNCLOS took effect in 1994 upon passage of key enabling amendments designed to spur commercial mining. -

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge Underwater Mountains and Hydrothermal Vent Zones Are Home to Distinctive Species and Valuable Minerals

A fact sheet from Jan 2018 NOAA The Mid-Atlantic Ridge Underwater mountains and hydrothermal vent zones are home to distinctive species and valuable minerals Overview The depths of the Atlantic Ocean are home to fascinating geological features and unusual life forms. The Mid- Atlantic Ridge (MAR) is a massive underwater mountain range, 1,700 to 4,200 meters (1 to 2.6 miles) below sea level, that runs from the Arctic Ocean to the Southern Ocean. It is a hot spot for hydrothermal vents, which provide habitat for unique species that could provide insight into the origins of life on Earth. Hydrothermal vents are fueled by underwater volcanic activity or seafloor spreading, and they spew superheated, mineral-laden water from beneath the ocean floor. As the water cools, minerals precipitate out, forming towers containing copper, gold, silver, and zinc. These minerals are used in electronics such as mobile phones and laptop computers and in cars, appliances, and bridges. Vent ecosystems support unique species, mostly bacteria, that derive their energy from mineral-rich vent waters rather than sunlight. These microbes form thick, nutrient-rich mats along the seafloor that support shrimp, mussels, worms, snails, and fish. The MAR’s vent fields were discovered only in 1985, and scientists expect future expeditions to reveal new vents and species.1 The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is responsible for managing deep-sea mining and protecting the marine environment from its impacts, has entered into exploration contracts along the MAR with France, Poland, and Russia. Once mining begins, equipment will remove or degrade habitats and create sediment plumes that could smother nearby life, while noise and light could also negatively affect deep-sea species. -

Deep Sea Mining MINERAL EXPLORATION in the PACIFIC

MARCH 2021 Deep sea mining MINERAL EXPLORATION IN THE PACIFIC Overview KEY STATS The Pacific Islands are already producers of transition minerals, including copper, cobalt and nickel, mined onshore in Papua New Guinea, Fiji and 2 New Caledonia. But the real opportunity to dramatically expand transition 1.5M+ km in the Pacific and Indian mineral production is offshore, in the deep sea. This opportunity comes oceans set aside for with significant human rights risks. mineral exploration In the last decade, companies and governments have increasingly pursued exploration of the deep sea, where minerals essential to renewable energy technology may be found in large quantities. Copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, manganese and rare earth elements (REEs) are all mineral exploration found on or below the Pacific seabed; none have yet been commercially contracts awarded mined. Given the current geographic concentration of some of these 30 to 21 companies minerals, companies and governments are eager to expand production to new geographies to diversify supply chains and guard against disruption. Exploration has begun in earnest, with more than 1.5 million squared kilometers in the Pacific and Indian oceans already set aside for mineral exploration, an area nearly the size of Mongolia. However, Indigenous groups and civil society organisations have raised 18/30 contracts are held by companied from: concerns about the potential for human rights abuse associated with seabed mining, including the potential destruction of Indigenous China S. Korea cultures and livelihoods and irreparable environmental damage to France India sensitive and critical ecosystems, including potential impacts on ocean biodiversity and sensitive food chains. -

Seabed Mapping: a Brief History from Meaningful Words

geosciences Review Seabed Mapping: A Brief History from Meaningful Words Pedro Smith Menandro and Alex Cardoso Bastos * Marine Geosciences Lab (Labogeo), Departmento Oceanografia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória-ES 29075-910, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 16 July 2020 Abstract: Over the last few centuries, mapping the ocean seabed has been a major challenge for marine geoscientists. Knowledge of seabed bathymetry and morphology has significantly impacted our understanding of our planet dynamics. The history and scientific trends of seabed mapping can be assessed by data mining prior studies. Here, we have mined the scientific literature using the keyword “seabed mapping” to investigate and provide the evolution of mapping methods and emphasize the main trends and challenges over the last 90 years. An increase in related scientific production was observed in the beginning of the 1970s, together with an increased interest in new mapping technologies. The last two decades have revealed major shift in ocean mapping. Besides the range of applications for seabed mapping, terms like habitat mapping and concepts of seabed classification and backscatter began to appear. This follows the trend of investments in research, science, and technology but is mainly related to national and international demands regarding defining that country’s exclusive economic zone, the interest in marine mineral and renewable energy resources, the need for spatial planning, and the scientific challenge of understanding climate variability. The future of seabed mapping brings high expectations, considering that this is one of the main research and development themes for the United Nations Decade of the Oceans. -

Intern Report

Insights from abyssal lebensspuren Jennifer Durden, University of Southampton, UK Mentors: Ken Smith, Jr., Christine Huffard, Katherine Dunlop Summer 2014 Keywords: lebensspuren, traces, abyss, megafauna, deposit-feeding, benthos, sediment ABSTRACT The seasonal input of food to the abyss impacts the benthic community, and changes to that temporal cycle, through changes to the climate and surface ocean conditions impact the benthic assemblage. Most of the benthic fauna are deposit feeders, and many leave traces (‘lebensspuren’) of their activity in the sediment. These traces provide an avenue for examining the temporal variations in the activity of these animals, with insights into the usage of food inputs to the system. Traces of a variety of functions were identified in photographs captured in 2011 and 2012 from Station M, a soft-sedimented abyssal site in the northeast Pacific. Lebensspuren creation, holothurian tracking, and lebensspuren duration were estimated from hourly time-lapse images, while trace densities, diversity and seabed coverage were assessed from photographs captured with a seabed- transiting vehicle. The creation rates and duration of traces on the seabed appeared to vary over time, and may have been related to food supply, as may tracking rates of holothurians. The density, diversity and seabed coverage by lebensspuren of different types varied with food supply, with different lag times for POC flux and salp coverage. These are interpreted to be due to selectivity of 1 deposit feeders, and different response times between trace creators. These variations shed light on the usage of food inputs to the abyss. INTRODUCTION Deep-sea benthic communities rely on a seasonal food supply of detritus from the surface ocean (Billett et al., 1983, Rice et al., 1986). -

Worksheets on Climate Change: Sea Level Rise

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT WORKSHEETS ON CLIMATE CHANGE Sea level rise Consequences for coastal and lowland areas: Bangladesh and the Netherlands Sea level rise – Consequences for coastal and lowland areas: Bangladesh and the Netherlands © Germanwatch 2014 Sea level rise Consequences for coastal and lowland areas: Bangladesh and the Netherlands As a consequence of the anthropogenic greenhouse effect A comparison of the two countries, the Netherlands and the scientific community predicts an increase in average Bangladesh, both of which are potentially very much jeop- global temperature and resulting sea level rise. Heated ardised by sea level rise, clearly illustrates the likely im- water, however, expands only slowly because of the heat pacts for humans and the environment, but also shows transfer from the atmosphere to the sea. For this reason, how different the capacities of individual countries are the sea responds to climate change like a slow-to-react concerning their ability to adapt and to protect them- monster – slow but persistent. In the 20th century the selves from the consequences. Bangladesh, one of the sea level already rose by an average of 12 to 22 cm. The poorest and at the same time most densely populated Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) con- countries in the world, is also one of the countries which cludes that, as a result of climate change, by 2100 the rise will be most affected by the expected sea level rise. in sea levels could increase worldwide by up to almost 1 metre compared to the mean sea level in the years Flooding has already caused damage up to 100 km inland 1986–2005. -

Conflicting Narratives of Deep Sea Mining

sustainability Review Conflicting Narratives of Deep Sea Mining Axel Hallgren 1 and Anders Hansson 1,2,* 1 Department of Thematic Studies: Environmental Change, Linköping University, S-581 83 Linköping, Sweden; [email protected] 2 Centre for Climate Science and Policy Research (CSPR), Linköping University, S-581 83 Linköping, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: As land-based mining industries face increasing complexities, e.g., diminishing return on investments, environmental degradation, and geopolitical tensions, governments are searching for alternatives. Following decades of anticipation, technological innovation, and exploration, deep seabed mining (DSM) in the oceans has, according to the mining industry and other proponents, moved closer to implementation. The DSM industry is currently waiting for international regulations that will guide future exploitation. This paper aims to provide an overview of the current status of DSM and structure ongoing key discussions and tensions prevalent in scientific literature. A narrative review method is applied, and the analysis inductively structures four narratives in the results section: (1) a green economy in a blue world, (2) the sharing of DSM profits, (3) the depths of the unknown, and (4) let the minerals be. The paper concludes that some narratives are conflicting, but the policy path that currently dominates has a preponderance towards Narrative 1—encouraging industrial mining in the near future based on current knowledge—and does not reflect current wider discussions in the literature. The paper suggests that the regulatory process and discussions should be opened up and more perspectives, such as if DSM is morally appropriate (Narrative 4), should be taken into consideration. -

Deep Sea Mining: the Underwater Gold Rush

Deep Sea Mining: The Underwater Gold Rush Executive Summary & Key Takeaways Long considered an industry of the far future, commercially viable Deep Sea Mining (DSM) is now imminent. Growing demand for these limited resources, paired with depleting terrestrial sources, technological advancements, and a push to rapidly finalize regulations means DSM is on the verge of taking off on a great commercial scale. The push for action is only intensified by current dependence of many countries, including the United States, on China to provide and process rare earth elements. Since the late 1990s, China has provided more than 90 percent of the world’s supply of rare earth elements by controlling at least 85 percent of the world’s capacity to process rare earth ores into material manufacturers can use. It also holds the most contracts to explore seabed mining areas that contain these rare earth elements and other critical minerals, such as cobalt and manganese. • Resources extracted from the deep sea could play a key role in renewable energy technology and other components of a low-carbon future. • The deep-sea ecosystems in which these resources are found are extremely remote, so relatively little is known about the biodiversity and ecosystem functions of these areas. • The ISA is dealing with a dual mandate to protect the environment and jumpstart the industry but has very limited information with which to form regulations. • There is disagreement about the amount of information needed before extractive mining activity can begin. What is Deep Sea Mining? Deep Sea Mining (DSM) is a collective term used to refer to extraction of three main resources of commercial interest: polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulfides, and cobalt rich crusts. -

Deep-Sea Mineral Potential in the South Pacific Region : Review of the Japan/SOPAC Deep-Sea Mineral Resources Study Programme

Deep-sea Mineral Potential in the South Pacific Region : Review of the Japan/SOPAC Deep-sea Mineral Resources Study Programme 著者 "OKAMOTO Nobuyuki" journal or 南太平洋海域調査研究報告=Occasional papers publication title volume 41 page range 21-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/9957 南太平洋海域調査研究報告 No.Deep-sea41(20 0Mineral5年3月) Potential in the South Pacific Region 21 OCCASIONAL PAPERS No.41( March 2005) Deep-sea Mineral Potential in the South Pacific Region - Review of the Japan/SOPAC Deep-sea Mineral Resources Study Programme- OKAMOTO Nobuyuki Abstract The Government of Japan and South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC) have been conducting joint surveys of deep-sea mineral resources in the Exclusive Economy Zones (EEZs) of SOPAC member countries, since 1985. The various research and government institutions that have been closely involved in this long-standing programme include: the Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA) and Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) which is the former Metal Mining Agency of Japan (MMAJ) and relevant ministries of the participating Pacific Island government. The survey programme is on-going using research vessel Hakurei-Maru No.2 which belongs to JOGMEC. This twenty year long, joint project initiative has been extremely successful in confirming the resource potential of the Pacific region through discovering valuable deep-sea mineral deposits such as manganese nodules in the Cook Islands waters, cobalt-rich manganese crusts in the Marshall Islands, Kiribati and Federated States of Micronesia, and polymetalic massive sulfides in the Fiji waters. Key words: cobalt-rich manganese crust, deep-sea mineral resources, manganese nodule, hydrothermal deposit Introduction Pacific Island countries consist of many small islands scattered over vast areas of ocean space (Fig.1). -

Pressure 4117, Tide 5217, Wave and Tide 5218

TD 302 OPERATING MANUAL PRESSURE SENSOR 4117/4117R TIDE SENSOR 5217/5217R WAVE & TIDE SENSOR 5217/5217R January 2014 PRESSURE SENSOR 4117/4117R TIDE SENSOR 5217/5217R WAVE AND TIDE SENSOR 5218/5218R Page 2 Aanderaa Data Instruments AS – TD302 1st Edition 30 June 2013 Preliminary 2nd Edition 05 September 2003 New version including general updates in text. Rebranded, Frame Work 3 update, please refer Product change notification AADI Document ID:DA-50009-01, Date: 09 December 2011 (ref Appendix 6 ). 3rd Edition 14 January 2014 New property “Installation Depth” added for Tide sensors, effective version 8.1.1 © Copyright: Aanderaa Data Instruments AS January 2014 - TD 302 Operating Manual for Pressure 4117/4117R Tide 5217/5217R, Wave & Tide 5218/5218R Page 3 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and scope ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Document overview.............................................................................................................................................. 6 Applicable documents .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (Goods) - Biogeographic Classification

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/14/INF/10 29 April 2010 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SUBSIDIARY BODY ON SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVICE Fourteenth meeting Nairobi, 10-21 May 2010 Item 3.1.3 of the provisional agenda * GLOBAL OPEN OCEANS AND DEEP SEABED (GOODS) - BIOGEOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION Note by the Executive Secretary 1. The Executive Secretary is circulating herewith, for the information of participants in the fourteenth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice, IOC Technical Series No.84 on Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (GOODS) - Biogeographic Classification, submitted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization/Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, pursuant to paragraph 6of decision IX/20. 2. This report was also considered by the CBD Expert Workshop on Scientific and Technical Guidance on the Use of Biogeographic Classification Systems and Identification of Marine Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in Need of Protection, held in Ottawa, from 29 September to 2 October 2009. 3. The document is circulated in the form and language in which it was received by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. * UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/14/1 /... In order to minimize the environmental impacts of the Secretariat’s processes, and to contribute to the Secretary-General’s initiative f or a C-Neutral UN, this document is printed in limited numbers. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copies to meetings and not to request additional copies. Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (GOODS) biogeographic classification Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (GOODS) biogeographic classification Edited by: Marjo Vierros (UNU-IAS), Ian Cresswell (Australia), Elva Escobar Briones (Mexico), Jake Rice (Canada), and Jeff Ardron (Germany) UNESCO 2009 goods inside 2.indd 1 24/03/09 14:55:52 Global Open Oceans and Deep Seabed (GOODS) biogeographic classification Authors Contributors Vera N.