Conflicting Narratives of Deep Sea Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

Deep Sea Mining on the Horizon?

May 2014 Home Subscribe Archive Contact Thematic focus: Environmental governance, Resource efficiency Wealth in the Oceans: Deep sea mining on the horizon? 2 The deep ocean, the largest biome on Earth at over 1 000 metres below the surface of the ocean, holds vast quantities of untapped energy resources, precious metals and minerals. Advancements in technology have enabled greater access to these treasures. As a result, deep sea mining is becoming increasingly possible. To date no commercial deep sea mining operation has taken place, but plans to open a deep sea mine have recently been announced. Our ability to anticipate the impacts of mining is limited by the lack of knowledge about deep sea biodiversity, ecosystem complexity, and the extent of environmental BYCC NC and social impacts from mining operations. As such, it is important that policies guiding mineral extraction from the deep seas are rooted into adaptive management – allowing for the integration of new scientific information alongside advances in technology. Governance mechanisms for international waters and the seabed need to be strengthened. The tanley Zimny/Flickr/ precautionary approach should be used to avoid repeating instances of S well-known destructive practices associated with conventional mining. Why is this issue important? Minerals and the metals they contain are an essential component of the modern high-tech world. As global stocks of raw mineral resources continue to dwindle due to increasing material consumption, intense demand for valuable metals has pushed up global prices. The result is that manufacturing industries are now seeking access to previously unattainable mineral deposits in the ocean depths. -

Deep-Sea Mining: the Basics

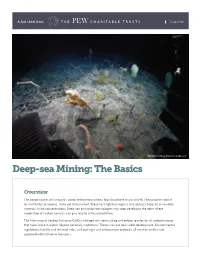

A fact sheet from June 2018 NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research Deep-sea Mining: The Basics Overview The deepest parts of the world’s ocean feature ecosystems found nowhere else on Earth. They provide habitat for multitudes of species, many yet to be named. These vast, lightless regions also possess deposits of valuable minerals in rich concentrations. Deep-sea extraction technologies may soon develop to the point where exploration of seabed minerals can give way to active exploitation. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is charged with formulating and enforcing rules for all seabed mining that takes place in waters beyond national jurisdictions. These rules are now under development. Environmental regulations, liability and financial rules, and oversight and enforcement protocols all must be written and approved within three to five years. Figure 1 Types of Deep-sea Mining Production support vessel Return pipe Riser pipe Cobalt Seafloor massive Polymetallic crusts sulfides nodules Subsurface plumes 800-2,500 from return water meters deep Deposition 1,000-4,000 meters deep 4,000-6,500 meters deep Cobalt-rich Localized plumes Seabed pump Ferromanganeseferromanganese from cutting crusts Seafloor production tool Nodule deposit Massive sulfide deposit Sediment Source: New Zealand Environment Guide © 2018 The Pew Charitable Trusts 2 The legal foundations • The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Also known as the Law of the Sea Treaty, UNCLOS is the constitutional document governing mineral exploitation on the roughly 60 percent of the world seabed that lies beyond national jurisdictions. UNCLOS took effect in 1994 upon passage of key enabling amendments designed to spur commercial mining. -

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge Underwater Mountains and Hydrothermal Vent Zones Are Home to Distinctive Species and Valuable Minerals

A fact sheet from Jan 2018 NOAA The Mid-Atlantic Ridge Underwater mountains and hydrothermal vent zones are home to distinctive species and valuable minerals Overview The depths of the Atlantic Ocean are home to fascinating geological features and unusual life forms. The Mid- Atlantic Ridge (MAR) is a massive underwater mountain range, 1,700 to 4,200 meters (1 to 2.6 miles) below sea level, that runs from the Arctic Ocean to the Southern Ocean. It is a hot spot for hydrothermal vents, which provide habitat for unique species that could provide insight into the origins of life on Earth. Hydrothermal vents are fueled by underwater volcanic activity or seafloor spreading, and they spew superheated, mineral-laden water from beneath the ocean floor. As the water cools, minerals precipitate out, forming towers containing copper, gold, silver, and zinc. These minerals are used in electronics such as mobile phones and laptop computers and in cars, appliances, and bridges. Vent ecosystems support unique species, mostly bacteria, that derive their energy from mineral-rich vent waters rather than sunlight. These microbes form thick, nutrient-rich mats along the seafloor that support shrimp, mussels, worms, snails, and fish. The MAR’s vent fields were discovered only in 1985, and scientists expect future expeditions to reveal new vents and species.1 The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is responsible for managing deep-sea mining and protecting the marine environment from its impacts, has entered into exploration contracts along the MAR with France, Poland, and Russia. Once mining begins, equipment will remove or degrade habitats and create sediment plumes that could smother nearby life, while noise and light could also negatively affect deep-sea species. -

CRYSTAL PEAK MINERALS INC. (Formerly EPM Mining Ventures Inc.)

CRYSTAL PEAK MINERALS INC. (Formerly EPM Mining Ventures Inc.) MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS For the Three Months Ended March 31, 2016 CRYSTAL PEAK MINERALS INC. (Formerly EPM Mining Ventures Inc.) Management Discussion and Analysis For the Three Months Ended March 31, 2016 This Management Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) of Crystal Peak Minerals Inc. (“CPM”) (formerly EPM Mining Ventures Inc. or “EPM”), together with its subsidiaries (collectively the “Company”), is dated May 19, 2016 and provides an analysis of the Company’s performance and financial condition for the three months ended March 31, 2016. CPM is listed on the TSX Venture Exchange (“TSXV”) and its common shares trade under the symbol “CPM” (formerly “EPK”). The Company’s common shares also trade on the OTCQX International (“OTCQX”) under the ticker symbol “CPMMF” (formerly “EPKMF”). This MD&A should be read in conjunction with the Company’s unaudited condensed interim consolidated financial statements (the “Interim Financial Statements”) for the three months ended March 31, 2016, including the related note disclosures. The Company’s Interim Financial Statements are prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). The Interim Financial Statements have been prepared under the historical cost convention, except in the case of fair value of certain items, and unless specifically indicated otherwise, are presented in United States dollars. The Interim Financial Statements, along with Certifications of Annual and Interim Filings and press releases, are available on the Canadian System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval (SEDAR) at www.sedar.com . Michael Blois, MBL Pr. Eng., is the Qualified Person in accordance with Canadian National Instrument 43-101 – Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (“NI 43-101”) who is responsible for the mineral processing and metallurgical testing, recovery methods, infrastructure, capital cost, and operating cost estimates described in this MD&A. -

Marine Snow Storms: Assessing the Environmental Risks of Ocean Fertilization

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Business and Law 1-1-2009 Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization Robin M. Warner University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lawpapers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Warner, Robin M.: Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization 2009, 426-436. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lawpapers/192 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Marine snow storms: Assessing the environmental risks of ocean fertilization Abstract The threats posed by climate change to the global environment have fostered heightened scientific interest in marine geo-engineering schemes designed to boost the capacity of the oceans to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide. This is the primary goal of a process known as ocean fertilization which seeks to increase the production of organic material in the surface ocean in order to promote further draw down of photosynthesized carbon to the deep ocean. This article describes the process of ocean fertilization, its objectives and potential impacts on the marine environment and some examples of ocean fertilization experiments. It analyses the applicability of international law principles on marine environmental protection to this process and the regulatory gaps and ambiguities in the existing international law framework for such activities. Finally it examines the emerging regulatory for legitimate scientific experiments involving ocean fertilization being developed by the London Convention and London Protocol Scientific Groups and its potential implications for the proponents of ocean fertilization trials. -

Marine Pollution: a Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 5 1-1972 Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R. Lanctot Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence R. Lanctot, Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime, 24 Hastings L.J. 67 (1972). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions-A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime By LAWRENCE R. LANCTOT* THE oceans are earth's last significant frontier for man's utiliza- tion. Advances in marine technology are opening previously unreach- able depths to permit the study of the oceans' mysteries and the extrac- tion of valuable natural resources.' Because these vast resources were inaccessible in the past, international law does not provide any certain rules governing the ownership and development of marine resources which lie beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.2 In response to this legal uncertainty and in the face of accelerating technology, the United Nations General Assembly has called a General Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1973 to formulate international conventions gov- erning the development of the seabed and ocean floor., Great interest * J.D., University of San Francisco, 1968; LL.M., Columbia University, 1969; Adjunct Professor of Law, University of San Francisco. -

Toxic Tide: the Threat of Marine Plastic Pollution in Australia

The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee Toxic tide: the threat of marine plastic pollution in Australia April 2016 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 ISBN 978-1-76010-400-9 Committee contact details PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3526 Fax: 02 6277 5818 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.aph.gov.au/senate_ec This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. This document was printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra Committee membership Committee members Senator Anne Urquhart, Chair ALP, TAS Senator Linda Reynolds CSC, Deputy Chair (from 12 October 2015) LP, WA Senator Anne McEwen (from 18 April 2016) ALP, WA Senator Chris Back (from 12 October 2015) LP, WA Senator the Hon Lisa Singh ALP, TAS Senator Larissa Waters AG, QLD Substitute member for this inquiry Senator Peter Whish-Wilson (AG, TAS) for Senator Larissa Waters (AG, QLD) Former members Senator the Hon Anne Ruston, Deputy Chair (to 12 October 2015) LP, SA Senator the Hon James McGrath (to 12 October 2015) LP, QLD Senator Joe Bullock (to 13 April 2016) ALP, WA Committee secretariat Ms Christine McDonald, Committee Secretary Mr Colby Hannan, Principal Research Officer Ms Fattimah Imtoual, Senior Research Officer Ms Kirsty Cattanach, Research Officer iii iv Table of Contents List of recommendations ..................................................................................vii List of abbreviations ....................................................................................... xiii Chapter 1: Introduction ..................................................................................... 1 Conduct of the inquiry ............................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgement ................................................................................................. -

Deep Sea Mining MINERAL EXPLORATION in the PACIFIC

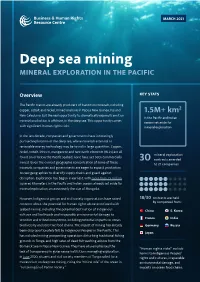

MARCH 2021 Deep sea mining MINERAL EXPLORATION IN THE PACIFIC Overview KEY STATS The Pacific Islands are already producers of transition minerals, including copper, cobalt and nickel, mined onshore in Papua New Guinea, Fiji and 2 New Caledonia. But the real opportunity to dramatically expand transition 1.5M+ km in the Pacific and Indian mineral production is offshore, in the deep sea. This opportunity comes oceans set aside for with significant human rights risks. mineral exploration In the last decade, companies and governments have increasingly pursued exploration of the deep sea, where minerals essential to renewable energy technology may be found in large quantities. Copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, manganese and rare earth elements (REEs) are all mineral exploration found on or below the Pacific seabed; none have yet been commercially contracts awarded mined. Given the current geographic concentration of some of these 30 to 21 companies minerals, companies and governments are eager to expand production to new geographies to diversify supply chains and guard against disruption. Exploration has begun in earnest, with more than 1.5 million squared kilometers in the Pacific and Indian oceans already set aside for mineral exploration, an area nearly the size of Mongolia. However, Indigenous groups and civil society organisations have raised 18/30 contracts are held by companied from: concerns about the potential for human rights abuse associated with seabed mining, including the potential destruction of Indigenous China S. Korea cultures and livelihoods and irreparable environmental damage to France India sensitive and critical ecosystems, including potential impacts on ocean biodiversity and sensitive food chains. -

Sustainability in the Minerals Industry: Seeking a Consensus on Its Meaning

sustainability Review Sustainability in the Minerals Industry: Seeking a Consensus on Its Meaning Juliana Segura-Salazar * ID and Luís Marcelo Tavares Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro—COPPE/UFRJ, Cx. Postal 68505, CEP 21941-972, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-21-2290-1544 (ext. 237/238) Received: 23 February 2018; Accepted: 24 April 2018; Published: 4 May 2018 Abstract: Sustainability science has received progressively greater attention worldwide, given the growing environmental concerns and socioeconomic inequity, both largely resulting from a prevailing global economic model that has prioritized profits. It is now widely recognized that mankind needs to adopt measures to change the currently unsustainable production and consumption patterns. The minerals industry plays a fundamental role in this context, having received attention through various initiatives over the last decades. Several of these have been, however, questioned in practice. Indeed, a consensus on the implications of sustainability in the minerals industry has not yet been reached. The present work aims to deepen the discussion on how the mineral sector can improve its sustainability. An exhaustive literature review of peer-reviewed academic articles published on the topic in English over the last 25 years, as well as complementary references, has been carried out. From this, it became clear that there is a need to build a better definition of sustainability for the mineral sector, which has been proposed here from a more holistic viewpoint. Finally, and in light of this new perspective, several of the trade-offs and synergies related to sustainability of the minerals industry are discussed in a cross-sectional manner. -

Marine Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Marine Public Disclosure Authorized Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste Public Disclosure Authorized Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant per- mission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rose- wood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Sea-Based Sources of Marine Litter – a Review of Current Knowledge and Assessment of Data Gaps (Second Interim Report of Gesamp Working Group 43, 4 June 2020)

August 2020 COFI/2020/SBD.8 8 E COMMITTEE ON FISHERIES Thirty-Fourth Session Rome, 1-5 February 2021 (TBC) SEA-BASED SOURCES OF MARINE LITTER – A REVIEW OF CURRENT KNOWLEDGE AND ASSESSMENT OF DATA GAPS (SECOND INTERIM REPORT OF GESAMP WORKING GROUP 43, 4 JUNE 2020) SEA-BASED SOURCES OF MARINE LITTER – A REVIEW OF CURRENT KNOWLEDGE AND ASSESSMENT OF DATA GAPS Second Interim Report of GESAMP Working Group 43 4 June 2020 GESAMP WG 43 Second Interim Report, June 4, 2020 COFI/2021/SBD.8 Notes: GESAMP is an advisory body consisting of specialized experts nominated by the Sponsoring Agencies (IMO, FAO, UNESCO-IOC, UNIDO, WMO, IAEA, UN, UNEP, UNDP and ISA). Its principal task is to provide scientific advice concerning the prevention, reduction and control of the degradation of the marine environment to the Sponsoring Organizations. The report contains views expressed or endorsed by members of GESAMP who act in their individual capacities; their views may not necessarily correspond with those of the Sponsoring Organizations. Permission may be granted by any of the Sponsoring Organizations for the report to be wholly or partially reproduced in publication by any individual who is not a staff member of a Sponsoring Organizations of GESAMP, provided that the source of the extract and the condition mentioned above are indicated. Information about GESAMP and its reports and studies can be found at: http://gesamp.org Copyright © IMO, FAO, UNESCO-IOC, UNIDO, WMO, IAEA, UN, UNEP, UNDP, ISA 2020 ii Authors: Kirsten V.K. Gilardi (WG 43 Chair), Kyle Antonelis, Francois Galgani, Emily Grilly, Pingguo He, Olof Linden, Rafaella Piermarini, Kelsey Richardson, David Santillo, Saly N.