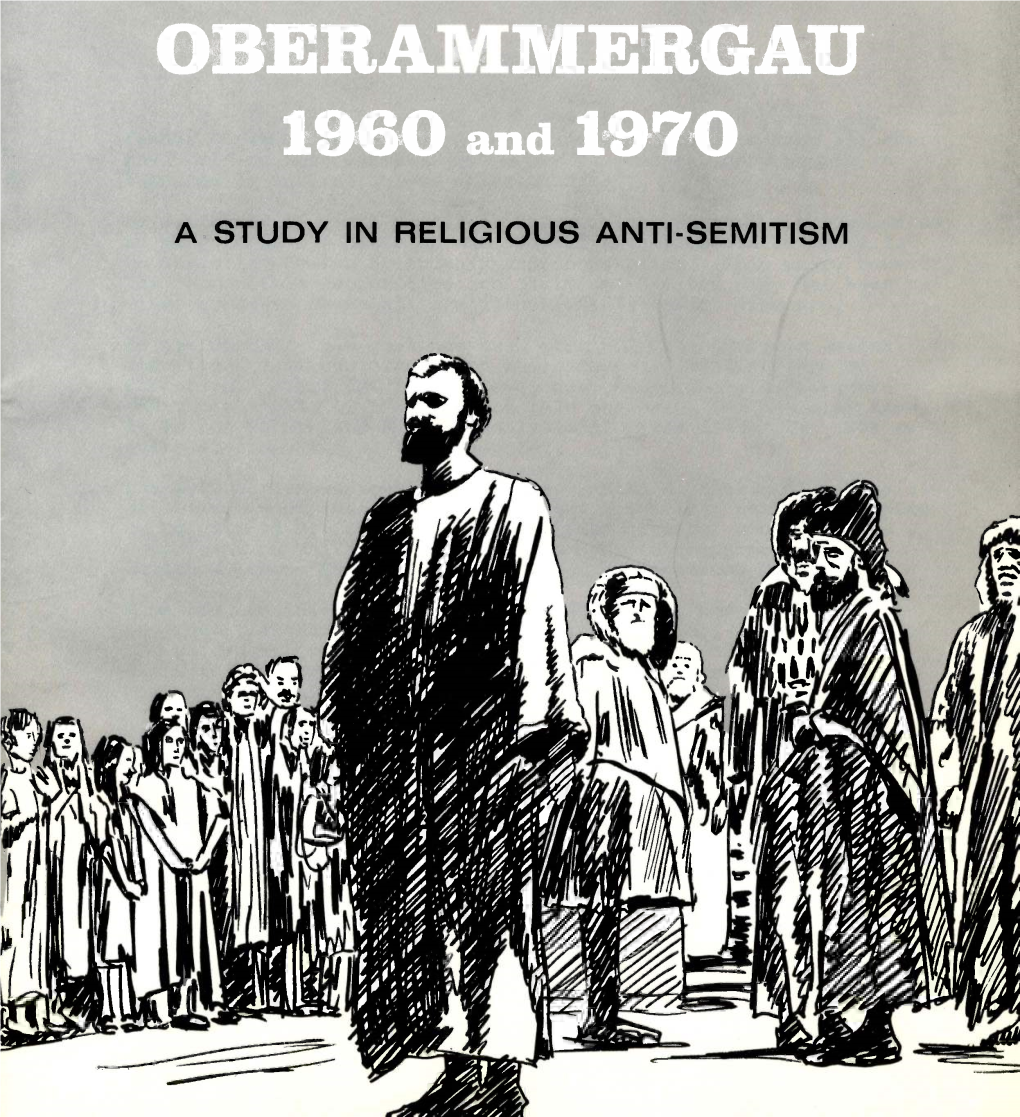

A Study in Religious Anti-Semitism Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

70. the Gospel of John—8:12-24

70. The Gospel of John—8:12-24 “The Light of the World” Pt.3 (5/5/19) In our study in John’s gospel we are currently in chapter 8 where we came across one of the seven “I Am” statements of Jesus that John built his gospel around. Every time Jesus called Himself “I AM”, He was declaring that He was the voice from the burning bush (Exodus 3:13-14) where God identified Himself to Moses as the great ‘I AM’. And so, as we study John 8, understand that the whole chapter is built around Jesus’ declaration of divinity—which led to a heated confrontation between Himself and His enemies. II. The Heated Confrontation—v.12-59 A. Round One—Light and Darkness (v.12–20) John 8:12 (NKJV) 12 Then Jesus spoke to them again, saying, "I am the light of the world. He who follows Me shall not walk in darkness, but have the light of life." And so, this very heated confrontation started with Jesus declaring Himself to be Yahweh (the great I AM) and Messiah—and ended with His enemies picking up stones to kill Him (v.59). The ‘them’ in verse 12 refers to the scribes and Pharisees (v.3)—the ‘scholars’ of Judaism. When Jesus called Himself “the light of the world”—it would have immediately reminded them that Yahweh was likened to ‘light’ in their Scriptures many times (Psalm 27:1; 84:11). 1 And so, when Jesus proclaimed, “I AM—the light of the world”—He was claiming to be the God of Israel—the radiant Shekinah Glory! It was the Shekinah Glory (presence of God in the form of a pillar of fire by night) that was the light that lit their ancestor’s way thru the darkness of the wilderness for those forty years before entering the Promised Land. -

Bloody Message

Volume 32 Number 4 Article 4 June 2004 Bloody Message Leendert van Beek Dordt College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation van Beek, Leendert (2004) "Bloody Message," Pro Rege: Vol. 32: No. 4, 20 - 25. Available at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege/vol32/iss4/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pro Rege by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Bloody Message after having received some criticism about it during the preview sessions. The actors still say the line in Aramaic, but there is no English. He is referring to this passage from Matthew 27:25: “Let his blood be on us and on our children.” 2 As an answer to the question of why the Jews have led such a wandering existence through the centuries and have been persecuted brutally, people, including Christians, sometimes quite “naturally” mention this phrase from Matthew 27. The Jews have invoked the curse upon themselves, haven’t they? Having thought about this text quite a bit since I saw the film, I can’t figure out why believing Christians have used a Bible verse to hurt other people. I would By Leendert van Beek have thought that Bible verses would be used, in the first place, to comfort people, not to persecute them. I’ve done some research on this text, and I would like to explain a specific reading of this notorious verse. -

Blood, People, and Crowds in Matthew, Luther, and Bach

Swarthmore College Works Music Faculty Works Music Spring 2005 Blood, People, And Crowds In Matthew, Luther, And Bach Michael Marissen Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-music Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Michael Marissen. (2005). "Blood, People, And Crowds In Matthew, Luther, And Bach". Lutheran Quarterly. Volume 19, Issue 1. 1-22. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-music/30 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BloodBlood, }People, People, and and Crowds Crowds in Matthew,in Matthew, Luther, andand Bach Bach by MICHAEMICHAELL MARISSENMARISSEN n allall ofof ChristianChristian Scripture,Scripture, probablprobablyy nnoo lineline hahass beenbeen invokeinvokedd toto Ijustifjustifyy theologicatheologicall condemnationcondemnation ofof JewsJews oror physicalphysical violenceviolence againstagainst JewJewss mormoree frequentlyfrequendy thanthan thethe outcryoutcry forfor Jesus'Jesus' crucifixioncrucifixion expressedexpressed byby "all"all thethe people"people" inin MatthewMatthew 27:25,27:25, "His"His bloobloodd bbee onon usus andand onon ourour children."children." ThisThis versversee appearsappears too,too, ofof course,course, iinn Bach'sBach's St.St. MatthewMatthew PassioPassionn (BWV(BWV 244)244),, andand iitt isis importantimportant toto askask hohoww -

The Rector's Corner the Early Church to Paint Clear Boundaries Between the Traditions, but That Context Was Quickly Lost As Th

the early church to paint clear boundaries between the traditions, but that context was quickly lost as the The Rector’s Corner teaching was passed on. Until very recently most By now I’m sure most of you know that I care deeply Christian denominations used John’s account and about words, particularly in regard to translation and Matthew’s description of the “blood curse” (we now understanding their use and intention as best as interpret Matthew 27:25 as referring to the possible in the original context of the community in destruction of Jerusalem 40 years later) to support which they emerged. For this Holy Week and the deliberately anti-Semitic policies and actions. It was Season of Easter there are two ways in which I’m only after the fruit of this destructive teaching was making some changes and I’d like to explain why and born in the Nazi death camps that we realized we how I’m doing so. Because our language and how we needed to change. use it matters. “Preachers [from the earliest times and The Passion and the Holocaust continuing into our own day] did not hesitate to remind their hearers of the guilt The reading of the entire Passion narrative is a of all Jews for the death of the Lord, with central part of Holy Week. We read the appropriate the consequence that quite commonly on cycle’s version on Palm Sunday (this year was Mark) Good Friday, Jewish families would remain and then always read John’s version on Good Friday. -

1 the Gospel of Matthew General Introduction the Gospel of Matthew Has Long Been the Most Popular of the Four Canonical Gospels

The Gospel of Matthew General Introduction The Gospel of Matthew has long been the most popular of the four canonical Gospels: consistently placed first in the canonical lists, it was widely used in early Christian communities, and for some time was thought to be the first Gospel written (though now we believe Mark was written first). Indeed, even today, people are often most familiar with Matthew’s Gospel. For example, over the next eight weeks, you’ll be encountering some of Jesus’ most famous teachings: “Love your enemies,” “Turn the other cheek,” “Do not be anxious about tomorrow,” “Let the children come,” “Go make disciples of all nations,” and the Lord’s prayer in the form most churches use today (as opposed to Luke’s version in Lk. 11:1-4). As the most Jewish of the four canonical Gospels, Matthew also provides a nice bridge between the two testaments of the Christian Bible. Author and Provenance According to tradition, this Gospel was written by Matthew (also called Levi), a former tax collector and one of Jesus’ twelve disciples (Mark 3:18; Matt 9:9; 10:3; Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13). The author implied by the text itself was clearly an early Jewish Christian who was well-educated and multilingual (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek). He was also an interpreter of earlier traditions, adopting and adapting several sources in the telling of his tale (the Gospel of Mark, a hypothetical sayings-source scholars call “Q,” the OT, oral tradition, and possibly a “special source” scholars call “M” or “special Matthew”). -

Gospel of Luke

Supplemental Notes: The Book of Luke Chuck Missler © 2001 Koinonia House Inc. Page 1 Audio Listing Audio Listing Luke Chapter 1 Luke Chapter 9 Introduction. Birth of John the Baptist. Annunciation of Messiah. The Twelve Disciples Sent. The Feeding of the 5,000. Jesus’ Identity and Mission. The Transfiguration. Luke Chapter 2 Luke Chapter 10 The Child and the Mosaic Law. The Years of Growth. The Good Samaritan. The Visit in Bethany. Luke Chapter 3 Luke Chapter 11 Ministry of John the Baptist. Baptism of Jesus. Genealogy of Christ. Jesus Instructs on: Prayer; Satan; Spiritual Opportunity; Hypocrisy. Luke Chapter 4 The Call to Obedience. The Temptation of Christ. The Demoniac. Luke Chapter 12 Luke Chapter 5 The Tyranny of Worry. The Call to Diligence. Jesus’ Mandate. Jesus’ Fame Spreads. Luke Chapter 13 Luke Chapter 6 Paradox Resolution. The Way of the Righteous is Narrow. Jesus Challenges Sabbath “Law.” Choosing the Twelve. Luke Chapter 14 Luke Chapter 7 Jesus Exposes Falsehoods: Popularity, Hospitality, Security. The Dis- tinctions Between Salvation and Discipleship. Jesus’ Ministry in Capernaum. Jesus’ Responses to Faith, Despair, Doubt, Love. Luke Chapter 15 Luke Chapter 8 The Lost Sheep. The Lost Coin. The Prodigal Son Why Parables? The Significance of Hems. Luke Chapter 16 Stewardship. The Rich Man and Lazarus. Contrasting Hades, Sheol, Gehenna, Tartarus, Abousso. Page 2 Page 3 Audio Listing Luke 1 Luke Chapter 17 General Background Predestination or Free Will. Revisit Paradox Resolution. Who was Luke? Generally assumed to be a Gentile (Cf. Col 4:11 and 14). The date and circumstances of his conversion are unknown. -

The Book of Hebrews

Supplemental Notes: The Book of Hebrews compiled by Chuck Missler © 2008 Koinonia House Inc. Audio Listing Hebrews Introduction and 1:1 - 3 Introduction. Authorship. Hebrews Chapters 1:4 - 14 Greater Than the Angels. Hebrews Chapter 2 The Role of Christ in Salvation. Warning #1: The Danger of Drifting. Acknowledgments Hebrews Chapter 3 These notes have been assembled from speaking notes and related materials which had been compiled from a number of classic and con- Greater Than Moses. The Disobedient Generation—Warning #2: The temporary commentaries and other sources detailed in the bibliography, Danger of Disobedience. as well as other articles and publications of Koinonia House. While we have attempted to include relevant endnotes and other references, we apologize for any errors or oversights. Hebrews Chapter 4 (and the rest of Chapter 3) The complete recordings of the sessions, as well as supporting diagrams, The Promise of Rest. Christ, The Way to God. maps, etc., are also available in various audiovisual formats from the publisher. Hebrews Chapter 5 Warning Against Apostasy. Priesthood of Melchisedec. Warning #3: Failing to Mature. Hebrews Chapter 6 Eternal Salvation Question. Call to Maturity. God’s Oath Unchang- ing. Hebrews Chapter 7 Jesus fulfills the Levitical Priesthood. Page 2 Page Audio Listing The Epistle to the Hebrews Session 1 Hebrews 1:1- 3 Hebrews Chapter 8 The Hebrew Christian Epistles Jesus as the Perfect Priest. The New Covenant. Not one of the last eight epistles (Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2, and 3 John, and Jude) are addressed to a church. These disturbing Hebrews Chapter 9 warnings seem to contrast with the assurances of the church epistles: Romans 8 vs. -

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series C: lnterreligious Activities. 1952-1992 Box 41 , Folder 7, Oberammergau Passion Play, Undated. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (513) 221-1875 phone, (513) 221-7812 fax americanjewisharchives.org ,_,. _... ...... The following Statement on Passion Plays was issued frow the office of the SecretariaL for Catholic-Jewish Relations of the National Confere.1ce of Catholic Bishops, on Fe:b.:-ua:-y 28, 1968. It was signe•l for the Executive Committee ty the foll o•..Jil"e mi:>mhers vno t ere p::-~sent at Hall Universi~y en the afore~entioned date, in consul~ation with the Board o~ Consul~ors of the Secretariat: Pt. ~ev. Msgr. George G. Hi£gin& Rt. Rev. Msgr. John M. Oesterre.!.12;1er ~ev. :Sdward H. Flannery Sister K. Hargrove, R.S.C. J. Rev. John B. Sheerin~ C.S. P. _____ .,,, .I -- ' ~ - ~- ' r- • . ' • ,.. I J "" - -'i, .. .- .;; ~ r- ~ , ' . ... \ :-- - A STATEMENT ON PASSION PLAYS Lent, more than any o-=1;er 11 turgical season, draws the attention of Catholics to the sufferings of Christ. In this holy season the Church calls its iai~hful to relive these sufferings, especially in its J{oly Week Liturgy. In m:my places it is cµstomary to supplement the Liturgy by piou.s practices, among which have been passion play~. Popular in the past, these pious representations of Christ's passion are still produced in a few places. Their primary purpose is to stimulate religious fervor, but, when they are carelessly written or produced, they may become a source of anti-Semitic reactions. -

His Blood Be on Us and on Our Children!”: a Contextual Study and Reevaluation of the Infamous Blood Curse

AJBT Volume 21(18), May 3, 2020 “HIS BLOOD BE ON US AND ON OUR CHILDREN!”: A CONTEXTUAL STUDY AND REEVALUATION OF THE INFAMOUS BLOOD CURSE Abstract After the horrors of the Holocaust, many churches began to reconsider their stance towards the Jews. This reconsideration consistently included the Gospel of Matthew’s statement, “His blood be on us and on our children!” For centuries, this “blood curse” has served as a basis for Christian anti-Jewish violence and Christian animus towards Jews. But perhaps this statement was never intended to lead to such atrocities. This article examines both this phrase’s textual and cultural context, concluding that the anti-Jewish slant was interpreted into the text itself. Keywords: Matthew, anti-Judaism, antisemitism, blood curse, interfaith Introduction The darkness of the Holocaust cast a spotlight onto Christianity. Germany, the country that initiated the Holocaust, had a population that was nearly entirely Christian.1 The Pope, one of the most respected Christians in the world, remained more or less silent throughout the tragedy. 2 Some Christians even went as far as staffing concentration camps.3 How could those who subscribed to a religion that taught “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mt 22:39)4 as the second most important commandment––second only to loving God with all of your heart, soul, and mind (Mt 22:36–37)––have followers or members who stood by and 1 “The German Church and the Nazi State,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed March 6, 2018, http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005206. -

Does the New Testament Teach Anti-Semitism? Part 2

www.thinkingfaith.co.nz Does the New Testament Teach Anti-Semitism? Part 2 In the first part of this article we examined the charge that the Gospel of John teaches Anti- Semitism. We evaluated the argument put forward by Bryan Bruce in his documentary Jesus – the Cold Case, that the Gospel of John portrays ‘the Jews’ as enemies of Christ and therefore enemies of God, and that it is ‘the Jews’ who are responsible for the death of Jesus. Bruce claims that the Gospel of John holds ‘the Jews’ responsible for Jesus death, therefore the Gospel of John is inherently Anti-Semitic. However, upon investigation we saw that the Greek word Ioudaios translated as ‘the Jews’ can be used in three ways. It can mean the Jewish nation, the people of the region of Judea, and the Judean leadership, the chief priests and Pharisees. It is my contention that Bruce failed to take seriously the context in which the word Ioudaios is found, and because of this arrives at an illegitimate understanding of the text. The second line in Bruce’s argument comes from the Gospel of Matthew where the people gathered before Pilate cry out for the blood of Jesus to be upon their heads (Matt 27:25), but even this passage needs to be read in context. Firstly, it is the Chief Priests and Pharisees that are reported to have bound Jesus and delivered him to Pilate (Matt 27:1-2). When Pilate offers the crowd the option of having Jesus freed, Matthew records that it is again the Chief Priests and Elders who manipulate the crowd and motivate them to demand the blood of Jesus (27:20). -

The Books of Jeremiah & Lamentations

Supplemental Notes: The Books of Jeremiah & Lamentations Compiled by Chuck Missler © 2007 Koinonia House Inc. Audio Listing Jeremiah Chapter 1 Introduction. Historical Overview. The Call. Jeremiah Chapters 2 - 5 Remarriage. The Ark. Return to Me. Babylon. Jeremiah Chapters 6 - 8 Temple Discourses. Idolatry and the Temple. Shiloh. Acknowledgments Jeremiah Chapters 9 - 10 These notes have been assembled from speaking notes and related Diaspora. Professional Mourners. Poem of the Dead Reaper. materials which had been compiled from a number of classic and con- temporary commentaries and other sources detailed in the bibliography, Jeremiah Chapters 11 - 14 as well as other articles and publications of Koinonia House. While we have attempted to include relevant endnotes and other references, Plot to Assassinate. The Prosperity of the Wicked. Linen Belt. we apologize for any errors or oversights. Jeremiah Chapters 15 - 16 The complete recordings of the sessions, as well as supporting diagrams, maps, etc., are also available in various audiovisual formats from the Widows. Withdrawal from Daily Life. publisher. Jeremiah Chapters 17 - 18 The Heart is Wicked. Potter’s House. Jeremiah Chapters 19 - 21 Foreign gods. Pashur. Zedekiah’s Oracle. Page 2 Page 3 Audio Listing Audio Listing Jeremiah Chapter 22 Jeremiah Chapters 33 -36 Throne of David. Shallum. Blood Curse. Concludes Book of Consolation. Laws of Slave Trade. City to be Burned. Rechabites. Jeremiah Chapter 23 Jeremiah Chapters 37 - 38 A Righteous Branch. Against False Prophets. Jeremiah’s experiences during siege of Jerusalem. Jeremiah Chapters 24 - 25 Jeremiah Chapter 39 Two Baskets of Figs. Ezekiel’s 430 Years. 70 Years. Fall of Jerusalem. -

The Gospel Matthew

Supplemental Notes: The Gospel of Matthew compiled by Chuck Missler © 2006 Koinonia House Inc. Audio Listing Introduction and Matthew 1 Introduction and Background. The Birth of Jesus Christ. Matthew 2 Visit of the Magi. Massacre at Bethlehem. Flight to Egypt. Return into Nazareth. Matthew 3 - 4 John the Baptist. The “Lamb of God”? The Two Messiah view. Acknowledgments Temptations and their principal source. The ownership of the nation(s). The cost of discipleship: leaving as well as cleaving. These notes have been assembled from speaking notes and related materials which had been compiled from a number of classic and Matthew 5 - 7: The “Sermon on the Mount” Part 1 contemporary commentaries and other sources detailed in the bibliog- raphy, as well as other articles and publications of Koinonia House. The Beatitudes. The Similitudes. The Lord’s Prayer. Treasure in Heaven. While we have attempted to include relevant end notes and other references, we apologize for any errors or oversights. Matthew 5 - 7: The “Sermon on the Mount” Part 2 The complete recordings of the sessions, as well as supporting dia- grams, maps, etc., are also available in various audiovisual formats from The Golden Rule. False Teachers. The Law of Christ. the publisher. Matthew 8 - 9 Calming the Storm. Demoniac at Gadara. The Call of Matthew. Jairus’ Daughter. Woman with the issue of blood. Matthew 10 - 11 The Twelve sent out. John the Baptist: response. Matthew 12 Sabbath issues. The Unpardonable Sin. Page 2 Page 3 Audio Listing Audio Listing Matthew 13 Matthew 24: The Olivet Discourse The Kingdom Parables. The Four Soils.