Pleistocene Park: the Regeneration of the Mammoth Steppe?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

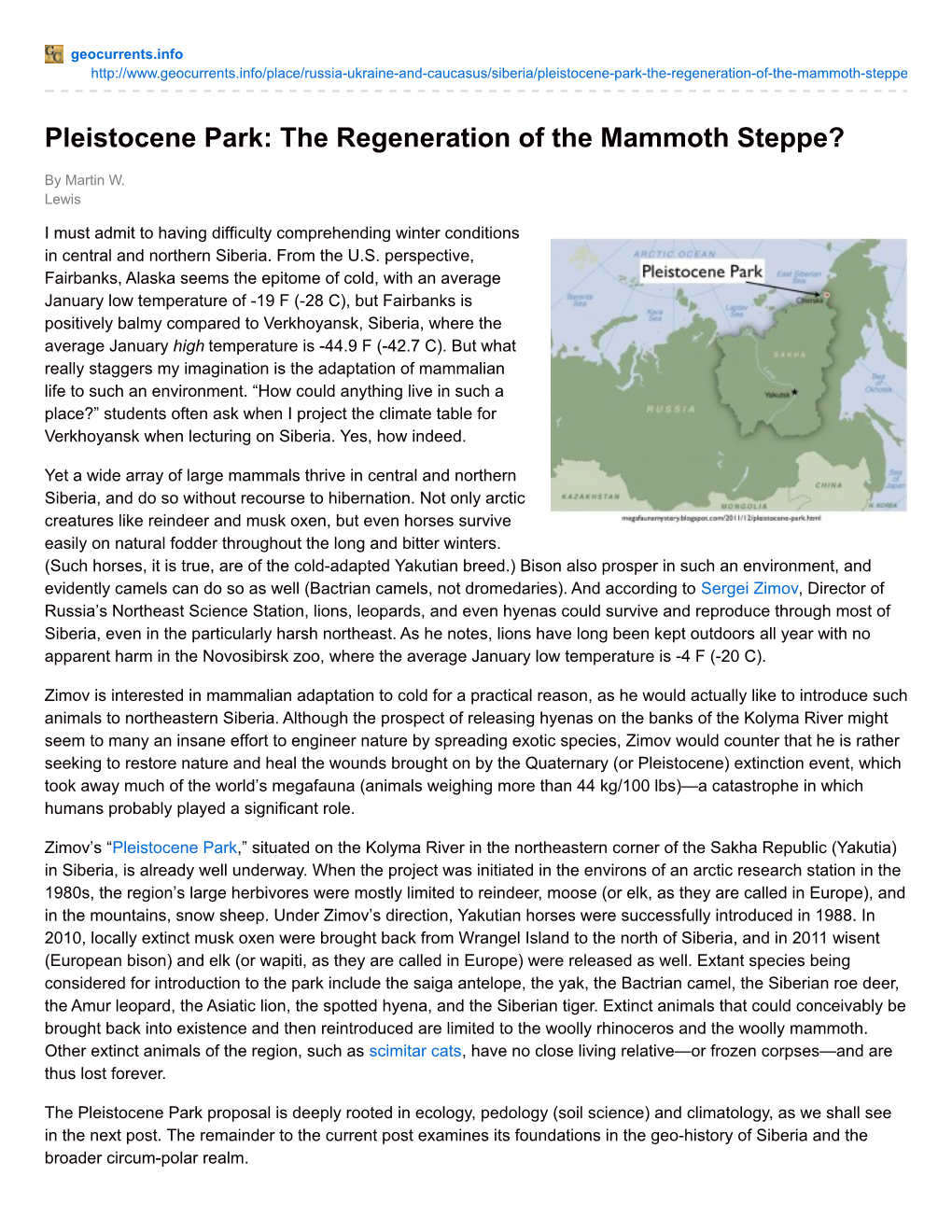

Recommended publications

-

Stanford's Last Fucks Reported Missing

VWDQIRUGÁLSVLGHFRP N@E8=I<< =C@GJ@;< J?FK>C8JJ j\\YXZb w ide.com Free Everywhere, $2.30 Canada Year 6, Issue 13, No. 163 ww.stanfordÁ ips HEADLINES Stanford’s Last Fucks Reported Missing Sources report Alan Worth, a sophomore known widely throughout campus as the last student with fucks in his possession may have lost the title this weekend. While anyone has aM\ \W ÅTM IV WNÅKQIT ZMXWZ\ ?WZ\P¼[ Abroad Student dorm mates came to the conclusion Experiences Internal that the fucks were no longer present Growth, Is Hospitalized upon stumbling past Worth’s double in Crothers last Saturday morning. Worth’s room was a ghastly display of apathetic release; reports indicate the presence of the usual: ubiquitous \ZI[PJZWSMVOTI[[WV\PMÆWWZ?WZ\P himself lying in a makeshift bed of Kim Jong Un Executes wide-ruled paper atop a small pool of crafted CHEM33 molecular model concerned that all evidence points to Himself After Looking in vomit and bodily excretion. However, Mirror “Dishonorably” WN _PI\ IXXMIZ[ \W JM IV MNÅOa WN most dorms rapidly converging to a also present were atypical signs of Dionysus. post-apocalyptic wasteland bereft of Get a good job. a mind pushed past the point of In an attempt to make light of any sort of motivation, Pettworther Do a good thing. depravity, such as the rhetorical “what these events Dean of Residence Dr. replied “Nah.” (Pitzer Adams, Apply to CodeHS. if God was one of us?” smeared on Ronald Pettworther was reached Foucart) Visit codehs.com/jobs the wall in feces and a meticulously for comment. -

Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: an Application to Bison and Sage Grouse

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-01 Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage Grouse Joshua Taft Kaze Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kaze, Joshua Taft, "Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage Grouse" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 4284. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4284 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage-Grouse in Utah Joshua T. Kaze A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Randy T. Larsen, Chair Steven Peterson Rick Baxter Department of Plant and Wildlife Science Brigham Young University December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Joshua T. Kaze All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage-Grouse in Utah Joshua T. Kaze Department of Plant and Wildlife Science, BYU Masters of Science Population growth for species with long lifespans and low reproductive rates (i.e., K- selected species) is influenced primarily by both survival of adult females and survival of young. Because survival of adults and young is influenced by habitat quality and resource availability, it is important for managers to understand factors that influence habitat selection during the period of reproduction. -

Uma Perspectiva Macroecológica Sobre O Risco De Extinção Em Mamíferos

Universidade Federal de Goiás Instituto de Ciências Biológicas Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Evolução Uma Perspectiva Macroecológica sobre o Risco de Extinção em Mamíferos VINÍCIUS SILVA REIS Goiânia 2019 VINÍCIUS SILVA REIS Uma Perspectiva Macroecológica sobre o Risco de Extinção em Mamíferos Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Evolução do Departamento de Ecologia do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ecologia e Evolução. Orientador: Profº Drº Matheus de Souza Lima- Ribeiro Co-orientadora: Profª Drª Levi Carina Terribile Goiânia 2019 DEDI CATÓRIA Ao meu pai Wilson e à minha mãe Iris por sempre acreditarem em mim. “Esper o que próxima vez que eu te veja, você s eja um novo homem com uma vasta gama de novas experiências e aventuras. Não he site, nem se permita dar desculpas. Apenas vá e faça. Vá e faça. Você ficará muito, muito feliz por ter feito”. Trecho da carta escrita por Christopher McCandless a Ron Franz contida em Into the Wild de Jon Krakauer (Livre tradução) . AGRADECIMENTOS Eis que a aventura do doutoramento esteve bem longe de ser um caminho solitário. Não poderia ter sido um caminho tão feliz se eu não tivesse encontrado pessoas que me ensinaram desde método científico até como se bebe cerveja de verdade. São aos que estiveram comigo desde sempre, aos que permaneceram comigo e às novas amizades que eu construí quando me mudei pra Goiás que quero agradecer por terem me apoiado no nascimento desta tese: À minha família, em especial meu pai Wilson, minha mãe Iris e minha irmã Flora, por me apoiarem e me incentivarem em cada conquista diária. -

Regional Patterns of Postglacial Changes in the Palearctic

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Regional patterns of postglacial changes in the Palearctic mammalian diversity indicate Received: 14 November 2014 Accepted: 06 July 2015 retreat to Siberian steppes rather Published: 06 August 2015 than extinction Věra Pavelková Řičánková, Jan Robovský, Jan Riegert & Jan Zrzavý We examined the presence of possible Recent refugia of Pleistocene mammalian faunas in Eurasia by analysing regional differences in the mammalian species composition, occurrence and extinction rates between Recent and Last Glacial faunas. Our analyses revealed that most of the widespread Last Glacial species have survived in the central Palearctic continental regions, most prominently in Altai–Sayan (followed by Kazakhstan and East European Plain). The Recent Altai–Sayan and Kazakhstan regions show species compositions very similar to their Pleistocene counterparts. The Palearctic regions have lost 12% of their mammalian species during the last 109,000 years. The major patterns of the postglacial changes in Palearctic mammalian diversity were not extinctions but rather radical shifts of species distribution ranges. Most of the Pleistocene mammalian fauna retreated eastwards, to the central Eurasian steppes, instead of northwards to the Arctic regions, considered Holocene refugia of Pleistocene megafauna. The central Eurasian Altai and Sayan mountains could thus be considered a present-day refugium of the Last Glacial biota, including mammals. Last Glacial landscape supported a unique mix of large species, now extinct or living in non-overlapping biomes, including rhino, bison, lion, reindeer, horse, muskox and mammoth1. The so called “mammoth steppe”2–4 community thrived for approximately 100,000 years without major changes, and then became extinct by the end of Pleistocene, around 12,000 years BP5,6. -

Mammal Extinction Facilitated Biome Shift and Human Population Change During the Last Glacial Termination in East-Central Europeenikő

Mammal Extinction Facilitated Biome Shift and Human Population Change During the Last Glacial Termination in East-Central EuropeEnikő Enikő Magyari ( [email protected] ) Eötvös Loránd University Mihály Gasparik Hungarian Natural History Museum István Major Hungarian Academy of Science György Lengyel University of Miskolc Ilona Pál Hungarian Academy of Science Attila Virág MTA-MTM-ELTE Research Group for Palaeontology János Korponai University of Public Service Zoltán Szabó Eötvös Loránd University Piroska Pazonyi MTA-MTM-ELTE Research Group for Palaeontology Research Article Keywords: megafauna, extinction, vegetation dynamics, biome, climate change, biodiversity change, Epigravettian, late glacial Posted Date: August 11th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-778658/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/27 Abstract Studying local extinction times, associated environmental and human population changes during the last glacial termination provides insights into the causes of mega- and microfauna extinctions. In East-Central (EC) Europe, Palaeolithic human groups were present throughout the last glacial maximum (LGM), but disappeared suddenly around 15 200 cal yr BP. In this study we use radiocarbon dated cave sediment proles and a large set of direct AMS 14C dates on mammal bones to determine local extinction times that are compared with the Epigravettian population decline, quantitative climate models, pollen and plant macrofossil inferred climate and biome reconstructions and coprophilous fungi derived total megafauna change for EC Europe. Our results suggest that the population size of large herbivores decreased in the area after 17 700 cal yr BP, when temperate tree abundance and warm continental steppe cover both increased in the lowlands Boreal forest expansion took place around 16 200 cal yr BP. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier

(This is a sample cover image for this issue. The actual cover is not yet available at this time.) This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Quaternary Science Reviews 57 (2012) 26e45 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Mammoth steppe: a high-productivity phenomenon S.A. Zimov a,*, N.S. Zimov a, A.N. Tikhonov b, F.S. Chapin III c a Northeast Science Station, Pacific Institute for Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Cherskii 678830, Russia b Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia c Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA article info abstract Article history: At the last deglaciation Earth’s largest biome, mammoth-steppe, vanished. Without knowledge of the Received 11 January 2012 productivity of this ecosystem, the evolution of man and the glacialeinterglacial dynamics of carbon Received in revised form storage in Earth’s main carbon reservoirs cannot be fully understood. -

Infectious Diseases of Saiga Antelopes and Domestic Livestock in Kazakhstan

Infectious diseases of saiga antelopes and domestic livestock in Kazakhstan Monica Lundervold University of Warwick, UK June 2001 1 Chapter 1 Introduction This thesis combines an investigation of the ecology of a wild ungulate, the saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica, Pallas), with epidemiological work on the diseases that this species shares with domestic livestock. The main focus is on foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) and brucellosis. The area of study was Kazakhstan (located in Central Asia, Figure 1.1), home to the largest population of saiga antelope in the world (Bekenov et al., 1998). Kazakhstan's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 led to a dramatic economic decline, accompanied by a massive reduction in livestock numbers and a virtual collapse in veterinary services (Goskomstat, 1996; Morin, 1998a). As the rural economy has disintegrated, the saiga has suffered a dramatic increase in poaching (Bekenov et al., 1998). Thus the investigation reported in this thesis includes ecological, epidemiological and socio-economic aspects, all of which were necessary in order to gain a full picture of the dynamics of the infectious diseases of saigas and livestock in Kazakhstan. The saiga is an interesting species to study because it is one of the few wildlife populations in the world that has been successfully managed for commercial hunting over a period of more than 40 years (Milner-Gulland, 1994a). Its location in Central Asia, an area that was completely closed to foreigners during the Soviet era, means that very little information on the species and its management has been available in western literature. The diseases that saigas share with domestic livestock have been a particular focus of this study because of the interesting issues related to veterinary care and disease control in the Former Soviet Union (FSU). -

The Giant Sea Mammal That Went Extinct in Less Than Three Decades

The Giant Sea Mammal That Went Extinct in Less Than Three Decades The quick disappearance of the 30-foot animal helped to usher in the modern science of human-caused extinctions. JACOB MIKANOWSKI, THE ATLANTIC 4/19/17 HTTPS://WWW.THEATLANTIC.COM/SCIENCE/ARCHIVE/2017/04/PLEIST OSEACOW/522831/ The Pleistocene, the geologic era immediately preceding our own, was an age of giants. North America was home to mastodons and saber-tooth cats; mammoths and wooly rhinos roamed Eurasia; giant lizards and bear-sized wombats strode across the Australian outback. Most of these giants died at the by the end of the last Ice Age, some 14,000 years ago. Whether this wave of extinctions was caused by climate change, overhunting by humans, or some combination of both remains a subject of intense debate among scientists. Complicating the picture, though, is the fact that a few Pleistocene giants survived the Quaternary extinction event and nearly made it intact to the present. Most of these survivor species found refuge on islands. Giant sloths were still living on Cuba 6,000 years ago, long after their relatives on the mainland had died out. The last wooly mammoths died out just 4,000 years ago. They lived in a small herd on Wrangel Island north of the Bering Strait between the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas. Two-thousand years ago, gorilla-sized lemurs were still living on Madagascar. A thousand years ago, 12-foot-tall moa birds were still foraging in the forests of New Zealand. Unlike the other long-lived megafauna, Steller’s sea cows, one of the last of the Pleistocene survivors to die out, found their refuge in a remote scrape of the ocean instead of on land. -

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach Joris Peters Ins/itu/ für Palaeoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin, Universität München. Feldmochinger Strasse 7, D-80992 München, Germany AchilIes Gautier Laboratorium VDor Pa/eonlo/agie, Seclie Kwartairpaleo1ltologie en Archeozoölogie, Universiteit Gent, Krijgs/aon 2811S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium James S. Brink National Museum, P. 0. Box 266. Bloemfontein 9300. Republic of South Africa Wim Haenen Instituut voor Gezandheidsecologie, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Capucijnenvoer 35, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium (Received 24 January 1992, revised manuscrip/ accepted 6 November 1992) Comparative osteomorphology and sta ti st ical analysis cf postcranial limb bone measurements cf modern African wildebeest (Collnochaetes), eland (Taura/ragus) and Africa n buffala (Sy" cer"s) have heen applied to reassess the systematic affiliations between these bovids and related extinct Pleistocene forms. The fossil sam pies come from the sites of Elandsfontein (Cape Province) .nd Flarisb.d (Orange Free State) in South Afrie • . On the basis of differenees in skull morphology and size of the appendicular skeleton between fossil and modern blaek wildebeest (ConlJochaeus gnou). the subspecies name anliquus, proposed earlier to designate the Pleistoeene form, ean be retained. The same taxonomie level is accepted for the large Pleistocene e1and, whieh could be named Taurolragus oryx antiquus. The long horned or giant buffa1o, Pelorovis antiquus, can be inc1uded in the polymorphous Syncerus caffer stock and could therefore be called Syncerus caffer antiquus. The ecology of Pleistocene and modern Connochaetes, Taurolragus and Syncerus is discussed. A relationship between herbivore body size and c1imate, as Bergmann's Rule predicts, could not be demonstrated. -

See the Light Inside Hellabrun Zoo’S Discovery Cave

QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA WINTERZ 2016 OO QUARIAISSUE 95 SEE THE LIGHT INSIDE HELLABRUN ZOO’S DISCOVERY CAVE To Russia with love REINTRODUCING THE PERSIAN LEOPARD 1 1 Majestic markhors AN EEP UPDATE FROM HELSINKI ZOO Contents Zooquaria Winter 2016 14 16 26 4 From the Director’s chair 18 Interview Our Director reports from the IUCN World Zooquaria talks to the outgoing and new Chairs of Conservation Congress the IUCN Species Survival Commission, Simon Stuart and Jon Paul Rodriguez 5 Noticeboard News from the world of conservation 21 Endangered species A creative solution that is helping to save the white- 6 Births & hatchings footed tamarin Magpies, foxes and turaco join the list of breeding successes 22 Conservation partners The benefits of collaboration between EAZA and 8 EAZA Annual Conference ALPZA EAZA’s annual conference is defined by its optimism for the future 23 EEP report Helsinki Zoo reports on the status and future of its 10 WAZA Conference Markhors EEP Why zoos and aquariums must be agents for change 24 Horticulture 11 EU Zoos Directive Planting ideas and solutions in action at Dublin Zoo How EAZA Members can take part in defining the future of the EU Zoos Directive. 26 Exhibits How the Discovery Cave at Hellabrun Zoo is helping 12 Campaigns visitors to overcome their phobias The Let It Grow campaign can help to demonstrate the importance of conserving local species 28 Education Can television and social media offer the same 14 Breeding programmes educational experience as a visit to the zoo? Reintroducing the Persian Leopard in the Caucasus 30 Resources 16 Conservation A visit to the ZSL Library will prove both informative How a combination of conservation initiatives and and inspiring research projects have helped to save the white stork Zooquaria EDITORIAL BOARD: EAZA Executive Office, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

Sexual Selection and Extinction in Deer Saloume Bazyan

Sexual selection and extinction in deer Saloume Bazyan Degree project in biology, Master of science (2 years), 2013 Examensarbete i biologi 30 hp till masterexamen, 2013 Biology Education Centre and Ecology and Genetics, Uppsala University Supervisor: Jacob Höglund External opponent: Masahito Tsuboi Content Abstract..............................................................................................................................................II Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 Sexual selection........................................................................................................................1 − Male-male competition...................................................................................................2 − Female choice.................................................................................................................2 − Sexual conflict.................................................................................................................3 Secondary sexual trait and mating system. .............................................................................3 Intensity of sexual selection......................................................................................................5 Goal and scope.....................................................................................................................................6 Methods................................................................................................................................................8