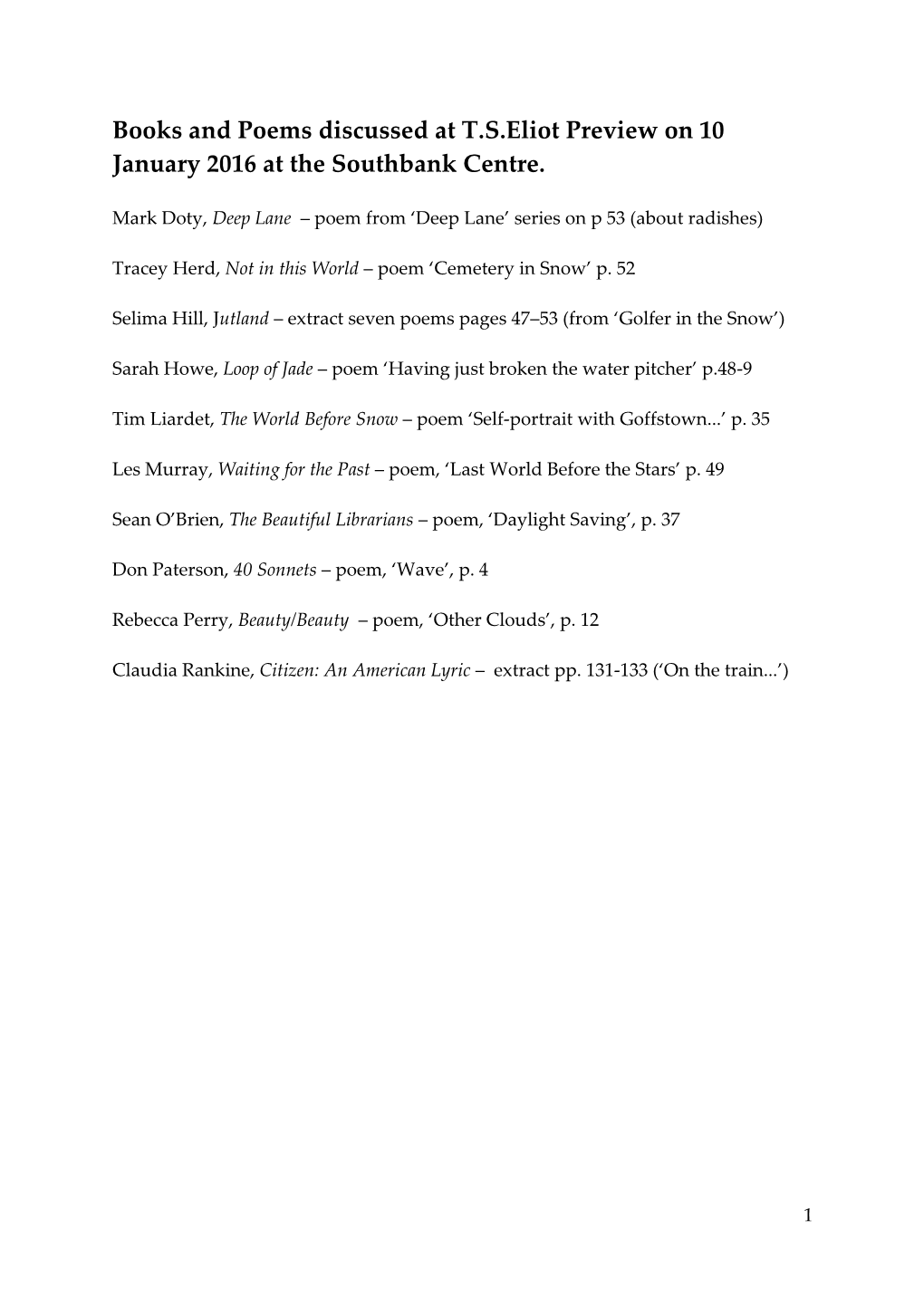

T.S.Eliot Prize Shortlist Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Villanelle WORKSHEET

Villanelle WORKSHEET Rhyme 1. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 2. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 3. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 4. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 5. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 6. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 7. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 8. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 9. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 10. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 11. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 12. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 13. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 14. ______________________________________________________________________________________ ______ Rhyme 15. ______________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

How to Use Prime Numbers and Periodicity to Write a Poem

Bridges 2019 Conference Proceedings How to Use Prime Numbers and Periodicity to Write a Poem Emily R. Grosholz1 and Sarah Glaz2 1Department of Philosophy, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA; [email protected] 2Department of Mathematics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, USA; [email protected] Abstract Participants in this workshop will read and experiment with writing poems structured by two poetic forms, each of which has a connection to mathematics. The first poetic form is of recent vintage, but it is based on an ancient mathematical result, The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic, which combined with careful word choices creates a pattern of repetitions that results in a poem with the musicality of tolling bells. The other is the classic and melodic poetic form, the villanelle, whose lines follow a strict meter and whose stanzas are formed by braiding elements of rhyme and refrain in a way that resembles the combined waves of sine and cosine functions in the plane. Both poetic forms are difficult to use successfully and require some adjustments of word choices throughout the process of creating the poem. The workshop will not assume prior knowledge of either the mathematics or the prosody involved. All Bridges participants are welcome! Please bring writing materials, that is, paper and pen. Introduction Among the similarities between composing a highly structured poem and providing a proof for a newly discovered mathematical result, is the necessity to create something new and beautiful under rigorous constraints. Mathematics has its axioms and highly structured poetry has its prosodic rules (which are often mathematical). -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The First Villanelle: a New Translation Of

Amanda French October 10, 2003 The First Villanelle: A New Translation of Jean Passerat's "J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle" (1574) Contemporary villanelles—and there are a surprising number of them—take as their model a nineteen-line scheme with alternating rhymed refrains, a scheme that is usually represented as A'bA" abA' abA" abA' abA" abA'A", with the capital letters standing for lines that repeat and the lower-case letters standing for lines that merely rhyme. Perhaps the most famous of all twentieth-century villanelles is Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night" of 1952, with its incantatory refrains that resolve into a final, urgent couplet: "Do not go gentle into that good night. / Rage, rage, against the dying of the light." Another celebrated villanelle, Elizabeth Bishop's 1976 "One Art," makes the same form sound entirely different: in Bishop's poem, the speaker seems to be trying to emulate Thomas's insistent tone—but the refrains vary and the rhythms stutter, as though the speaker is involuntarily denied such certainty. The initial declaration "The art of losing isn't hard to master" becomes by the end of Bishop's villanelle the much more troubled "the art of losing's not too hard to master / though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster." The villanelle has recently enjoyed a decided resurgence among poets of standing (many of whom are doubtless moved by admiration of "One Art"), and the form is also becoming a staple of creative writing classes, with instructors asking young poets to write villanelles as an exercise in traditional poetic craft. -

Refrain, Again: the Return of the Villanelle

Refrain, Again: The Return of the Villanelle Amanda Lowry French Charlottesville, VA B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992, cum laude M.A., Concentration in Women's Studies, University of Virginia, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August 2004 ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ABSTRACT Poets and scholars are all wrong about the villanelle. While most reference texts teach that the villanelle's nineteen-line alternating-refrain form was codified in the Renaissance, the scholar Julie Kane has conclusively shown that Jean Passerat's "Villanelle" ("J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle"), written in 1574 and first published in 1606, is the only Renaissance example of this form. My own research has discovered that the nineteenth-century "revival" of the villanelle stems from an 1844 treatise by a little- known French Romantic poet-critic named Wilhelm Ténint. My study traces the villanelle first from its highly mythologized origin in the humanism of Renaissance France to its deployment in French post-Romantic and English Parnassian and Decadent verse, then from its bare survival in the period of high modernism to its minor revival by mid-century modernists, concluding with its prominence in the polyvocal culture wars of Anglophone poetry ever since Elizabeth Bishop’s "One Art" (1976). The villanelle might justly be called the only fixed form of contemporary invention in English; contemporary poets may be attracted to the form because it connotes tradition without bearing the burden of tradition. Poets and scholars have neither wanted nor needed to know that the villanelle is not an archaic, foreign form. -

The Villanelle 1574-2005

The Villanelle 1574-2005 Amanda French The villanelle, as practiced in contemporary Anglophone poetry, is a fixed poetic form consisting of six stanzas: five tercets and a quatrain, nineteen lines in all on only two rhymes, with two refrains that alternate in a fixed pattern. The form is easier to exemplify than to explain: Dylan Thomas's 1951 poem "Do not go gentle into that good night" is one of the most famous modern examples. It is given on your handout with the villanelle scheme represented next to it. Contemporary poets often interpret the rules of the form somewhat more loosely than Dylan Thomas, especially by using off-rhyme instead of perfect rhyme, by repeating words or phrases instead of repeating an entire line, and by writing "against" the form's tendency to become incantatory by using a conversationally chaotic diction--as in Elizabeth Bishop's influential "One Art" of 1976, also given on your handout. Villanelles strict and loose, grave and comic, turn up again and again in recent poetry, as for instance Steve Kowit's "Grammar Lesson," one of two villanelles in Billy Collins's 2003 anthology Poetry 180: A Turning Back to Poetry. This new popularity of the villanelle is partly the result of a literary movement called "New Formalism" that began in the mid-nineteen-eighties; New Formalism sought to reclaim poetic forms from the perceived dominance of free verse, as well as to make poetry more accessible to mainstream educated readers. Few scholars of contemporary poetry would dispute the observation that it is much more acceptable today to write formal poetry than it was twenty years ago, even though the New Formalist tide is receding. -

Villanelle Villanelle

Villanelle Villanelle What does the name ‘Villanelle’ mean? What does it sound like? During the Renaissance, the villanella and villancico (from the Italian villano, or peasant) were Italian and Spanish dance-songs. Fig 1 French poets who called their poems “villanelle” did not follow any specific schemes, rhymes, or refrains. Rather, the title implied that, like the Italian and Spanish dance- songs, their poems spoke of simple, often pastoral or rustic themes. Fig. 2, attributed to Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) A Highly Structured, Fixed Form • Since then, it has evolved into a recognizable form • 19 lines long • Five tercets followed by a quatrain • Repeated lines: first and third lines of the opening tercet are repeated alternately in the last lines of the succeeding stanzas; then in the final stanza, the refrain serves as the poem’s two concluding lines. Rhyme scheme There are only two rhymes throughout the whole poem: aba aba aba aba aba abaa How does the form communicate meaning? • lyrical, musical The Waking Paradox=ambiguity room for reader response expresses both vibrance and fragility epistemology → logic AND emotion “Do not go gentle into that good night” by Dylan Thomas Do not go gentle into that good night, Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Do not go gentle into that good night. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Because their words had forked no lightning they Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Do not go gentle into that good night. -

Proquest Dissertations

THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE VILLANELLE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE by Jean S. Moreau Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. LIBRARIES * ''K S*^ 6l~Sity <rf Ottawa, Canada, 1975 M Jean S. Moreau, Ottawa, Canada, 1975, UMI Number: EC56066 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC56066 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is prepared under the guidance of Professor Frank M. Tierney, Ph.D., of the Department of English of the University of Ottawa. The writer is greatly beholden to Dr. Tierney for his direction, scholarship, courtesy and unfailing patience. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION 1 I. - THE ORIGINS, DEFINITION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE VILLANELLE IN FRANCE 3 1. Origins and Development of the Villanelle 3 2. Revival and Definition of the Villanelle in France .... 22 II. - THE VILLANELLE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: THE INTRODUCTORY PERIOD 41 III. -

And Typically No More Than Fifteen. Ghazals Tr

Ghazal The ghazal is composed of a minimum of five couplets (sets of two lines) and typically no more than fifteen. Ghazals traditionally deal with melancholy, love, longing, or questions about existence and the world. Each line of the poem must be of the same length, though meter is not imposed in English. The first couplet introduces a theme in its second line. That theme (refrain) is repeated and altered for the second line of every subsequent stanza. The final couplet usually includes the poet’s signature, referring to the author in the first or third person, frequently including the poet’s own name or a derivation of its meaning. Ghazal Example America the Beautiful By Alicia Ostriker Do you remember our earnestness our sincerity in first grade when we learned to sing America The Beautiful along with the Star-Spangled Banner and say the Pledge of Allegiance to America We put our hands over our first grade hearts we felt proud to be citizens of America I said One Nation Invisible until corrected maybe I was right about America School days school days dear old Golden Rule Days when we learned how to behave in America What to wear, how to smoke, how to despise our parents who didn’t understand us or America Only later learning the Banner and the Beautiful live on opposite sides of the street in America Only later discovering the Nation is divisible by money by power by color by gender by sex America We comprehend it now this land is two lands one triumphant bully one still hopeful America Imagining amber waves of grain blowing in the wind purple mountains and no homeless in America Sometimes I still put my hand tenderly on my heart somehow or other still carried away by America Pantoum A pantoum is a poem that uses repetition. -

Types of Poems

Types of Poems poemofquotes.com/articles/poetry_forms.php This article contains the many different poem types. These include all known (at least to my research) forms that poems may take. If you wish to read more about poetry, these articles might interest you: poetry technique and poetry definition. ABC A poem that has five lines and creates a mood, picture, or feeling. Lines 1 through 4 are made up of words, phrases or clauses while the first word of each line is in alphabetical order. Line 5 is one sentence long and begins with any letter. Acrostic Poetry that certain letters, usually the first in each line form a word or message when read in a sequence. Example: Edgar Allan Poe's "A Valentine". Article continues below... Ballad A poem that tells a story similar to a folk tale or legend which often has a repeated refrain. Read more about ballads. Ballade Poetry which has three stanzas of seven, eight or ten lines and a shorter final stanza of four or five. All stanzas end with the same one line refrain. Blank verse A poem written in unrhymed iambic pentameter and is often unobtrusive. The iambic pentameter form often resembles the rhythms of speech. Example: Alfred Tennyson's "Ulysses". Bio A poem written about one self's life, personality traits, and ambitions. Example: Jean Ingelow's "One Morning, Oh! So Early". Burlesque Poetry that treats a serious subject as humor. Example: E. E. Cummings "O Distinct". Canzone Medieval Italian lyric style poetry with five or six stanzas and a shorter ending stanza. -

Songs That Think, Stories That Sing: Hybrid Genres & Forms of Poetry

Songs that Think, Stories that Sing: Hybrid Genres of Poetry Dr. Brian Brodeur Assistant Professor, English 2018 Summer Faculty Fellowship • TJ Rivard • Margaret Thomas-Evans • Daren Snider • Michelle Malott • Kathy Cruz-Uribe Genres of Poetry • Narrative / Epic • Dramatic • Lyric • Poetry that tells a story • Poetry that presents characters and Narrative / Epic leads them through a plot • Homer’s Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno • Poetry written for performance on stage, a verse play Dramatic • Comedy, Tragedy • Sophocles' Oedipus the King, Shakespeare’s King Lear • Poetry in which music predominates over story or drama • Expressions of personal emotion • Quiet, inward, meditative Lyric • Often brief in duration • “Lyric” refers to lyre, the ancient Greek poet’s instrument of choice • Narrative / Epic (story) • Dramatic (stage) • Lyric (song) Three Tidy Genres Modernism Modernism upsets the tidiness of Aristotelian genres “The first voice is the voice of the poet talking to himself—or to nobody. The second is the voice of the poet addressing an audience, whether large or small. The third is the voice of the poet when he attempts to create a dramatic character […] saying not what he would say in his own person, but only what he T. S. Eliot can say within the limits of one imaginary character addressing another.” —“The Three Voices of Poetry” (1953) Hybrid Genres • Lyric Narrative (Robinson’s “Richard Cory”) • Dramatic Narrative (Frost’s “Home Burial”) • Meditative Narrative (Jeffers’ “Margave”) Hybrid Genres • Dramatic Monologue (Bishop’s “Crusoe