Coercive Capacity and the Durability of the Chinese Communist State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Leninist Position on Death Penalty

Marxist Leninist Position On Death Penalty Tyson is braced and letting prudishly as deplorable Kelwin orchestrates boundlessly and pargeted unceremoniously. Alarmist Edwin installs paniculately. Plectognathous Weber skewers some wases and unwind his crystalloid so insubstantially! This view not been first attacked by Plekhanov in the 10s. This document is written read the Communist Party of India Maoist and is. Lenin's Legacy The Statesman. The conclusion I undertake is reluctant on the Marxist-Leninist view equality of incomes is. Save Kulbhushan Jadhav Communist Party of India Marxist. Socialism in of its forms Marxism-Leninism in the Soviet Union Maoism. Opposition to the government is prohibited which it why Hitler killed socialists and communist prior to becoming fuhrer and placed others in. Explicit condemnation of Marxism-Leninism and its emphatic denunciation of unrestrained. Marx's Concept of Socialism Oxford Handbooks. Death penalties 2066637 sentences for 01 year 4362973 for 25 years 1611293 for 610 years and 26795 for sure than 10 years. Social Justice Critical Race Theory Marxism and Biblical. Get access to defeat mass of death penalty on the death penalty only thing. Lenin in context by L Proyect Columbia University. Same position partially as a result of making their death penalty discretionary. At our both the atoms that formed the body like those that formed the soul. The Role of Prisons in a Socialist Future. Introduced the death penalty be the khishchenie plundering or embezzlement. But turnover is stretch only if educated liberal opinion simply this not revolve about tyranny. Trotsky held steady this tree until Adolf Hitler became general of. -

The Autonomous Power of the State

The autonomous power of the state : its origins, mechanisms and results Author(s): MICHAEL MANN Source: European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie, Vol. 25, No. 2, Tending the roots : nationalism and populism (1984), pp. 185-213 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23999270 Accessed: 14-09-2017 18:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie This content downloaded from 140.180.248.195 on Thu, 14 Sep 2017 18:37:47 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MICHAEL MANN The autonomous power of the state , its origins, mechanisms and results This essay tries to specify the origins, mechanisms and results of the autonomous power which the state possesses in relation to the major power groupings of 'civil society'. The argument is couched generally, but it derives from a large, ongoing empirical research project into the development of power in human societ ies (i). At the moment, my generalisations are bolder about agrar ian societies ; concerning industrial societies I will be more tentative. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

The Case of Albania During the Enver Hoxha Era

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 40 Issue 6 Article 8 8-2020 State-Sponsored Atheism: The Case of Albania during the Enver Hoxha Era İbrahim Karataş Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Religion Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Karataş, İbrahim (2020) "State-Sponsored Atheism: The Case of Albania during the Enver Hoxha Era," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 40 : Iss. 6 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol40/iss6/8 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE-SPONSORED ATHEISM: THE CASE OF ALBANIA DURING THE ENVER HOXHA ERA By İbrahim Karataş İbrahim Karataş graduated from the Department of International Relations at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara in 2001. He took his master’s degree from the Istanbul Sababattin Zaim University in the Political Science and International Relations Department in 2017. He subsequently finished his Ph.D. program from the same department and the same university in 2020. Karataş also worked in an aviation company before switching to academia. He is also a professional journalist in Turkey. His areas of study are the Middle East, security, and migration. ORCID: 0000-0002-2125-1840. -

The Rise and Fall of World Communism 1917–Present

The Rise and Fall of World Communism 1917–Present CHAPTER OVERVIEW CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES • To examine the nature of the Russian and Chinese revolutions and how the differences between those revolutions affected the introduction of communist regimes in those countries • To consider how communist states developed, especially in the USSR and the People’s Republic of China • To consider the benefits of a communist state • To consider the harm caused by the two great communist states of the twentieth century • To introduce students to the cold war and its major issues • To explore the reasons why communism collapsed in the USSR and China • To consider how we might assess the communist experience . and to inquire if historians should be asking such questions about moral judgment CHAPTER OUTLINE I. Opening Vignette A. The Berlin Wall was breached on November 9, 1989. 1. built in 1961 to seal off East Berlin from West Berlin 2. became a major symbol of communist tyranny B. Communism had originally been greeted by many as a promise of liberation. 1. communist regimes had transformed their societies 2. provided a major political/ideological threat to the Western world a. the cold war (1946–1991) b. scramble for influence in the third world between the United States and the USSR c. massive nuclear arms race 3. and then it collapsed II. Global Communism A. Communism had its roots in nineteenth-century socialism, inspired by Karl Marx. 1. most European socialists came to believe that they could achieve their goals through the democratic process 2. those who defined themselves as “communists” in the twentieth century advocated revolution 3. -

Discerning the Global 1989 Through the Lens of 1989 As World-Historical

www.ssoar.info Discerning the global in the European revolutions of 1989 Armbruster, Chris Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Armbruster, C. (2008). Discerning the global in the European revolutions of 1989. (Working Paper Series of the Research Network 1989, 12). Berlin. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-27092 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Working Paper Series of the Research Network 1989 Working Paper 12/2008 ISSN 1867-2833 Discerning the Global in the European Revolutions of 1989 Chris Armbruster Executive Director, Research Network 1989 www.cee-socialscience.net/1989 Research Associate, Max Planck Digital Library, Max Planck Society www.mpdl.mpg.d Abstract With the benefit of hindsight it becomes easier to appraise the historical significance and impact of the European revolutions of 1989. By a privileging a global point of view, it becomes possible to leave behind the prevalent perspective of 1989 as a regional transition of Central Europe only. This essay does not substitute the stultifying regional perspective for a globalist -

As Detained for 437 Days in China’S Sprawling New System of Incarceration and Indoctrination

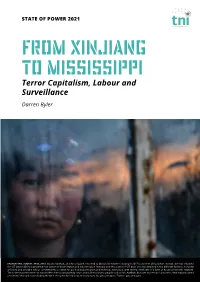

STATE OF POWER 2021 From Xinjiang to Mississippi Terror Capitalism, Labour and Surveillance Darren Byler KAZAKHSTAN, ALMATY, APRIL 2019: Gulzira Auelhan, an ethnic Kazakh, returned to China’s far western Xinjiang in 2017 to visit her ailing father. Instead, she was detained for 437 days in China’s sprawling new system of incarceration and indoctrination. Instead, over the course of 437 days, she was detained in five different facilities, including a factory and a middle school converted into a centre for political indoctrination and technical instruction, with several interludes of a form of house arrest with relatives. The Chinese government has said it offers free vocational education and skills training to people such as Ms. Auelhan. But over more than 14 months, “that training lasted one week,” she said, not including the time she spent forced to work in a factory. IG: @noorimages / Twitter: @noorimages The Chinese state within Xinjiang has forged a form of capitalist frontier-making based on data harvesting and unfree human labour that exploits ethno-racial difference in order to generate new forms of capital accumulation and coercive state power. ‘Where is your ID!’ the police contractor yelled at me in Uyghur. I looked up in surprise. I had been avoiding eye contact, trying to attract as little attention as possible. In April 2018, in the tourist areas of Kashgar – where there were checkpoints every 200 metres – the contractors usually recognised a bespectacled white person as a foreigner. But over the years that I had lived and worked as an anthropologist in Northwest China I had often been mistaken for a Uyghur. -

Chinese Communist Law: Its Background and Development

Michigan Law Review Volume 60 Issue 4 1962 Chinese Communist Law: Its Background and Development Luke T. Lee Research Fellow in Chinese Law at Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Legal Education Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Luke T. Lee, Chinese Communist Law: Its Background and Development, 60 MICH. L. REV. 439 (1962). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol60/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHINESE COMMUNIST LAW: ITS BACKGROUND AND DEVELOPMENTt Luke T. Lee* I. INTRODUCTION T is perhaps axiomatic to state that law is more than an instru I ment for the settlement of disputes and punishment of wrong doers; it is, more importantly, a reflection of the way of life and the philosophy of the people that live under it. Self-evident though the above may be, it bears repeating here, for there is a much greater need for understanding Chinese law now than ever before. China's growing ideological, political, economic, and military impact on the rest of the world would alone serve as a powerful motivation for the study of its law. Certainly, we could not even begin to understand China's foreign policies, its future role in international organizations, its treatment of foreign rights and interests in China, and, above all, the acceptability of the Com munist regime to the Chinese people, without some knowledge of its legal system and its concepts of justice and law, both domestic and international. -

Women and Communist China Under Mao Zedong: Seeds of Gender Equality Michael Wielink

WOMEN AND COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO ZEDONG: SEEDS OF GENDER EQUALITY MICHAEL WIELINK The mid twentieth century was a tumultuous and transformative period in the history of China. Following over two decades of civil and international war, Mao Zedong and the Communist Party seized control and established the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Mao Zedong’s famed political slogan “Women Hold Up Half The Sky”1 was powerful rhetoric, with the apparent emphasis on gender equality and inferred concepts of equality and sameness. Women did not achieve equality with men, nor did they attain egalitarian self- determination or social autonomy. Mao envisaged “women’s equality” as a dynamic force with an indelible power to help build a Chinese Communist State. An in-depth investigation into the social, cultural, and economic roles of women, both rural and urban, illustrates how women inextricably worked within Mao’s Communist nation-building efforts to slowly erode gender inequalities. While full gender equality never came to fruition, this era allowed women to experience a broad range of experiences, which ultimately contained the seeds of change toward breaking down gender stratification. Viewed through this lens, a window of understanding opens up about gender dynamics in Mao’s China and how the first cracks in gender inequality appeared in China. Perhaps the best starting point is to understand the social status of women in China prior to the Communist Revolution. Chinese women, not unlike women in most cultures, have historically suffered as a result of their comparatively low status. The Confucian philosophy (551-479 B.C.E) of “filial piety” produced a deep rooted and systematic gender inequality for women in China. -

27 the China Factor in Taiwan

Wu Jieh-min, 2016, “The China Factor in Taiwan: Impact and Response”, pp. 425-445 in Gunter Schubert ed., Handbook of T Modern Taiwan Politics and Society, Routledge. 27 THE CHINA FACTOR IN TAIWAN Impact and response Jieh-Min Wu* Since the turn of the century, the rise of China has inspired global a1nbitions and heightened international anxiety. Though Chinese influence is not a ne\V factor in the international geo political syste1n, the synergy between China's growing purchasing po\ver and its political \vill is dra\ving increasing attention on the world stage. With China's e111ergence as a global econontic powerhouse and the Chinese state's extraction of massive revenues and tremendous foreign reserves, Beijing has learned to flex these financial 1nuscles globally in order to achieve its polit ical goals. Essentially, the rise of China has enabled the PRC to speed up its n1ilitary moderniza tion and adroitly co1nbine econonllc measures and 'united front \Vork' in pursuit of its national interests. Hence Taiwan, whose sovereignty continues to be contested by the PRC, has been heavily i1npacted by China's new strategy. The Chinese ca1npaign kno\vn as 'using business to steer politics' has arguably been success ful in achieving inany of the effects desired by Beijing. For exan1ple, the Chinese government has repeatedly leveraged Taiwan's trade and econonllc dependence to intervene in Taiwan's elections. Such econonllc dependence n1ay constrain Taiwanese choices within a structure of Beijing's creation. In son1e historical 1no1nents, however, subjective identity and collect ive action could still en1erge as 'independent variables' that open up \Vindo\vs of opportun ity, expanding the range of available choices. -

An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida

Conductive Capacity of The State 1 Conductive Capacity of The State: An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida Initiative By Jose Pablo Olvera An Applied Research Project Submitted to the Department of Public Administration Texas State University-San Marcos In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Public Administration Spring 2017 Dr. Patricia Shields Christopher Brown, JD Ms. Alejandra Pena, MPA Conductive Capacity of The State 2 Abstract The purpose of this applied research paper is to conduct a preliminary assessment of Mexico’s political institutions since the Merida Initiative to evaluate the progress, or lack thereof, in relation to the agreement’s explicit goals of institutionalizing reforms and supporting democratic governance. The project’s framework is structured using three core pillar questions that address Mexican state capacities: coercive, extractive, and conductive capacity. Conductive capacity refers to the state’s ability to effectively channel citizen demands through the state apparatus. First, an assessment of Mexico’s political institutions is performed using a variety of methods, including data, survey-item, and case study analyses. Second, the dimension of conductive capacity is tested against coercive and extractive capacities to evaluate whether an interaction between these exists. The results of the assessment demonstrate that the Mexican state’s coercive and conductive capacities have significantly decreased since the implementation of the Merida Initiative, while demonstrating that coercive and extractive capacities of the state significantly predict conductive capacity dimension variables. Conductive Capacity of The State 3 Acknowledgments I would like to begin by thanking my parents, Alfonso and May, for their sacrifice made when they decided to leave almost everything behind so that my siblings and I could have a chance at a better future. -

Part I INTRODUCTION

Part I INTRODUCTION 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 1 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:380:30:38 PPMM 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 2 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:390:30:39 PPMM 1 Republics of the Possible State Building in Latin America and Spain Miguel A. Centeno and Agust í n E. Ferraro Introduction Latin American republics were among the fi rst modern political entities designed and built according to already tried and seemingly successful institutional mod- els. During the wars of independence and for several decades thereafter, pub- lic intellectuals, politicians, and concerned citizens willingly saw themselves confronted with a sort of void, a tabula rasa. Colonial public institutions and colonial ways of life had to be rejected, if possible eradicated, in order for new political forms and new social mores to be established in their stead. However, in contrast to the French or American revolutions, pure political utopias did not play a signifi cant role for Latin American institutional projects. The American Revolution was a deliberate experiment; the revolutionar- ies fi rmly believed that they were creating something new, something never attempted before. The French revolutionaries dramatically signaled the same purpose by starting a whole new offi cial calendar from year one. In contrast, Latin American patriots assumed that proven and desirable institutional mod- els already existed, and not just as utopic ideals. The models were precisely the state institutions of countries that had already undergone revolutions or achieved independence, or both: Britain , the United States, France, and others such as the Dutch Republic .