Viewing Change Through the Prism of Indigenous Human Ecology: Findings from the Afghan and Tajik Pamirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Und Leute 22

Vorwort 11 Herausragende Sehenswürdigkeiten 12 Das Wichtigste in Kurze 14 Entfernungstabelle 20 Zeichenlegende 20 LAND UND LEUTE 22 Tadschikistan im Überblick 24 Landschaft und Natur 25 Gewässer und Gletscher 27 Klima und Reisezeit 28 Flora 29 Fauna 32 Umweltprobleme 37 Geschichte 42 Die Anfänge 42 Vom griechisch-baktrischen Reich bis zur Kushan-Dynastie 47 Eroberung durch die Araber und das Somonidenreich 49 Türken, Mongolen und das Emirat von Buchara 49 Russischer Einfluss und >Great Game< 50 Sowjetische Zeit 50 Unabhängigkeit und Burgerkrieg 52 Endlich Frieden 53 Tadschikistan im 21. Jahrhundert 57 Regierung 57 Wirtschaftslage 58 Kritik und Opposition 58 Tourismus 60 Politisches System in Theorie und Praxis 61 Administrative Gliederung 63 Wirtschaft 65 Bevölkerung und Kultur 69 Religionen und Minderheiten 71 Städtebau und Architektur 74 Volkskunst 77 Sprache 79 Literatur 80 Musik 85 Brauche 89 http://d-nb.info/1071383132 Feste 91 Heilige Statten 94 Die tadschikische Küche 95 ZENTRALTADSCHIKISTAN 102 Duschanbe 104 Geschichte 104 Spaziergang am Rudaki-Prospekt 110 Markt und Mahalla 114 Parks am Varzob-Fluss 115 Museen 119 Denkmaler 122 Duschanbe live 128 Duschanbe-Informationen 131 Die Umgebung von Duschanbe 145 Festung Hisor 145 Varzob-Schlucht 148 Romit-Tal 152 Tal des Karatog 153 Wasserkraftwerk Norak 154 Das Rasht-Tal 156 Ob-i Garm 158 Gharm 159 Jirgatol 159 Reiseveranstalter in Zentral tadschikistan 161 DER PAMIR 162 Das Dach der Welt 164 Ein geografisches Kurzportrait 167 Die Bewohner des Pamirs 170 Sprache und Religion 186 Reisen -

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia The MCCS Mission Work in Eastern Turkestan 1892-1938 by John Hultvall A translation by Birgitta Åhman into English of the original book, Mission och revolution i Centralasien, published by Gummessons, Stockholm, 1981, in the series STUDIA MISSIONALIA UPSALIENSIA XXXV. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Gunnar Jarring Preface by the author I. Eastern Turkestan – An Isolated Country and Yet a Meeting Place 1. A Geographical Survey 2. Different Ethnic Groups 3. Scenes from Everyday Life 4. A Brief Historical Survey 5. Religious Concepts among the Chinese Rulers 6. The Religion of the Masses 7. Eastern Turkestan Church History II. Exploring the Mission Field 1892 -1900. From N. F. Höijer to the Boxer Uprising 1. An Un-known Mission Field 2. Pioneers 3. Diffident Missionary Endeavours 4. Sven Hedin – a Critic and a Friend 5. Real Adversities III. The Foundation 1901 – 1912. From the Boxer Uprising to the Birth of the Republic. 1. New Missionaries Keep Coming to the Field in a Constant Stream 2. Mission Medical Care is Organized 3. The Chinese Branch of the Mission Develops 4. The Bible Dispute 5. Starting Children’s Homes 6. The Republican Frenzy Reaches Kashgar 7. The Results of the Founding Years IV. Stabilization 1912 – 1923. From Sjöholm’s Inspection Tour to the First Persecution. 1. The Inspection of 1913 2. The Eastern Turkestan Conference 3. The Schools – an Attempt to Reach Young People 4. The Literary Work Transgressing all Frontiers 5. The Church is Taking Roots 6. The First World War – Seen from a Distance 7. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Long-Term Hydro–Climatic Trends in the Mountainous Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia

water Article Long-Term Hydro–Climatic Trends in the Mountainous Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia Aminjon Gulakhmadov 1,2,3,4 , Xi Chen 1,2,*, Nekruz Gulahmadov 2,4,5 , Tie Liu 2 , Rashid Davlyatov 4,6, Safarkhon Sharofiddinov 4,6 and Manuchekhr Gulakhmadov 1,5,6 1 Research Center of Ecology and Environment in Central Asia, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (M.G.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (T.L.) 3 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734064, Tajikistan 4 Institute of Water Problems, Hydropower and Ecology of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734042, Tajikistan; [email protected] (R.D.); [email protected] (S.S.) 5 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 6 Committee for Environmental Protection under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734034, Tajikistan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-991-782-3131 Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 25 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Hydro–climatic variables play an essential role in assessing the long-term changes in streamflow in the snow-fed and glacier-fed rivers that are extremely vulnerable to climatic variations in the alpine mountainous regions. The trend and magnitudinal changes of hydro–climatic variables, such as temperature, precipitation, and streamflow, were determined by applying the non-parametric Mann–Kendall, modified Mann–Kendall, and Sen’s slope tests in the Kofarnihon River Basin in Central Asia. -

Dedicated to Henk Rabau (1966–2017) Henk, May You Ever Float

Dedicated to Henk Rabau (1966–2017) Henk, may you ever float amongst the colours of Pamir, which you always said was heaven on earth. Your smile was real. Thanks for everything, dear friend. Without your energy, your creativity and ingenuity, our film would never have happened. Sleep tight. Pieter-Jan The children of The Land of the Enlightened 10 Foreword 11 Pieter-Jan De Pue – better still: ‘PJ’, as he is known – is the most ‘healthily international prizes. In 2017, Pieter-Jan received the Flemish Culture Prize curious’ person I have ever met. When you get to know him, he initially for Film. The title of this book, The Kings of Afghanistan, pays homage to comes across as a kind of contemporary explorer. Classic explorers would its main characters, the Afghan children who, through romantic dreams travel to all four corners of the globe in order to improve and civilise and creative pragmatism, manage to survive in this gigantic, mercilessly people in Europe’s image. When Marco Polo, Vasco De Gama and finally beautiful country. Stanley departed for far-off lands, theirs was not a cultural mission, but a political and economic one wrapped in a veneer of culture and religion. Pieter-Jan graduated from the RITS in Brussels in 2006 as a filmmaker, They travelled to other parts of the world to improve them, to civilise but he first discovered Afghanistan as a photographer. In exchange for them in their own and our image, and above all, to derive economic profit travel and accommodation expenses, he photographed the country for from them along the way. -

Decentralized Electrification of Suyuek in Xinjiang

Decentralized Electrification of Suyuek in Xinjiang EDF Solution for Decentralized Rural Electrification Asia Pacific Branch, EDF R&D, EDF Group CONTENTCONTENT • Brief introduction of EDF Activities • EDF’s solution for Decentralized Electrification • Introduction of Suyuek Decentralized Rural Electrification project BriefBrief IntroductionIntroduction ofof EDFEDF • Public Electrical Company, be responsible for power generation and distribution of electricity. • Public service mission • Power Installation 120GW (101.2GW in France) * Nuclear 62.3% * Hydro 20.1% * Thermal 17.6% EDF INTERNATIONAL INVESTISSEMENT Hydro & Gas Nuclear Other Renewable 7.3% 10.5% 6% 25.2% CCGT IGCC Coal 20% 1% 38.2% EDFEDF’’ss solutionsolution forfor decentralizeddecentralized electrificationelectrification • Situation in France * 10000 isolating sites far from the grid * Most of these isolated sites have been electrified by EDF through decentralized electrification EDFEDF’’ss solutionsolution forfor decentralizeddecentralized electrificationelectrification • Programme ACCESS * 4 existing Projects: - 2 projects in Mali in Africa - 1 project in Morocco - 1 project in South Africa * Supplied population 100,000 (still augment) * Under developing projects -Laos - Madagascar - Philippines SuyuekSuyuek decentralizeddecentralized ruralrural electrificationelectrification projectproject • Background of the project • Participants of the project • Project Description ENR conference in Bonn, june 2004, China’s declaration : “By 2010 the capacity of renewable energy will -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

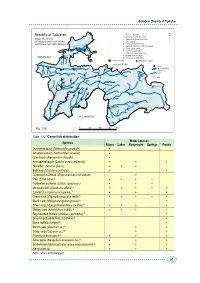

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

Sudanworkingpaper

SUDANWORKINGPAPER Comparing borderland dynamics Processes of territorialisation in the Nuba Mountains in Sudan, southern Yunnan in China, and the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan Leif Ole Manger Department of Social Anthropology, (UiB) Universtity of Bergen SWP 2015: 3 The programme Assisting Regional Universities in Sudan and South Sudan (ARUSS) aims to build academic bridges between Sudan and South Sudan. The overall objective is to enhance the quality and relevance of teaching and research in regional universities. As part of the program, research is carried out on a number of topics which are deemed important for lasting peace and development within and between the two countries. Efforts are also made to influence policy debates and improve the basis for decision making in both countries as well as among international actors. ARUSS is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. About the author Leif Ole Manger is Professor in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Bergen. His research has emphasis on the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean, with long-term field research in the Sudan, and shorter fieldworks in Yemen, Hyderabad, India, Singapore and China. His research focuses on economic and ecological anthropology, development studies, planning, land tenure, trade, communal labour, Arabization and Islamization. Mixing a broad cultural historical understanding of a region with current events is also important in Manger’s latest work on borders and borderland populations. Regionally this work focuses the borderland situations between Sudan and the new nation state of South Sudan, between post-Soviet Tajikistan, China and Afghanistan, and between contemporary China, Myanmar and India. -

Miocene Exhumation of the Pamir Revealed by Detrital Geothermochronology of Tajik Rivers C

TECTONICS, VOL. 31, TC2014, doi:10.1029/2011TC003040, 2012 Miocene exhumation of the Pamir revealed by detrital geothermochronology of Tajik rivers C. E. Lukens,1 B. Carrapa,1,2 B. S. Singer,3 and G. Gehrels2 Received 4 October 2011; revised 6 February 2012; accepted 26 February 2012; published 18 April 2012. [1] The Pamir mountains are the western continuation of the Tibetan-Himalayan system, the largest and highest orogenic system on Earth. Detrital geothermochronology applied to modern river sands from the western Pamir of Tajikistan records the history of sediment source crystallization, cooling, and exhumation. This provides important information on the timing of tectonic processes, relief formation, and erosion during orogenesis. U-Pb geochronology of detrital zircons and 40Ar/39Ar thermochronology of white micas from five rivers draining distinct tectonic terranes in the western Pamir document Paleozoic through Cenozoic crystallization ages and a Miocene (13–21 Ma) cooling signal. Detrital zircon U-Pb ages show Proterozoic through Cenozoic ages and affinity with Asian rocks in Tibet. The detrital 40Ar/39Ar data set documents deep and regional exhumation of the Pamir mountains >30 Myr after Indo-Asia collision, which is best explained with widespread erosion of metamorphic domes. This exhumation signal coincides with deposition of over 6 km of conglomerates in the adjacent foreland, documenting high subsidence, sedimentation, and regional exhumation in the region. Our data are consistent with a high relief landscape and orogen-wide exhumation at 13–21 Ma and correlate with the timing of exhumation of the Pamir gneiss domes. This exhumation is younger in the Pamir than that observed in neighboring Tibet and is consistent with higher magnitude Cenozoic deformation and shortening in this part of the orogenic system. -

1 Paradise Lost: Tajik Representations of Afghan

Paradise Lost: Tajik Representations of Afghan Badakhshan ABSTRACT In 2003 a Tajik film crew was permitted to cross the tightly controlled border into Afghan Badakhshan in order to film scenes for a commemorative documentary Sacred Traditions in Sacred Places. Although official state policies and international non- governmental organizations’ discourses concerning the Tajik-Afghan border have increasingly stressed freer movement and greater connectivity between the two sides, this strongly contrasts with the lived experience of Tajik Badakhshanis. The film crew was struck by the great disparity in the daily lives and lifeways of Ismaili Muslims on either side of this border, but also the depth of their shared past and present. This paper explores at times contradictory narratives of nostalgia and longing recounted by the film crew through the documentary film itself and in interviews with the film crew during film production and screening. I claim that emotions like nostalgia and longing are an affective response and resource serving to help Tajik Badakhshanis understand and manage daily life in a highly regulated border zone. INTRODUCTION In a darkened editing room in Dom Kino (‘film house’) in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, we watch footage of sweeping vistas of northern Afghanistan, close-ups of rushing mountain streams, and landscapes dotted with shepherds herding flocks across high pasture. The film’s research coordinator is seated next to me, and every few moments she sighs. She is struggling to decide which of these images will end up on the cutting room floor. “I was in paradise at that time,” she says, “I was in paradise at that moment….” In far southeastern Tajikistan the border with Afghanistan is the Panj River, in some places wide and rushing and in other places shallow and calm enough for a person to wade across. -

Engaging Central Asia

ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA THE EUROPEAN UNION’S NEW STRATEGY IN THE HEART OF EURASIA EDITED BY NEIL J. MELVIN CONTRIBUTORS BHAVNA DAVE MICHAEL DENISON MATTEO FUMAGALLI MICHAEL HALL NARGIS KASSENOVA DANIEL KIMMAGE NEIL J. MELVIN EUGHENIY ZHOVTIS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute based in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound analytical research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe today. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors writing in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect those of CEPS or any other institution with which the authors are associated. This study was carried out in the context of the broader work programme of CEPS on European Neighbourhood Policy, which is generously supported by the Compagnia di San Paolo and the Open Society Institute. ISBN-13: 978-92-9079-707-4 © Copyright 2008, Centre for European Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: 32 (0) 2 229.39.11 Fax: 32 (0) 2 219.41.51 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ceps.eu CONTENTS 1. Introduction Neil J. Melvin ................................................................................................. 1 2. Security Challenges in Central Asia: Implications for the EU’s Engagement Strategy Daniel Kimmage............................................................................................ -

Vulnerability Assessment Bartang

Ecosystem-based Adaptation in Central Asia Vulnerability of High Mountain Ecosystems to Climate Change in Tajikistan’s Bartang Valley – Ecological, Social and Economic Aspects – with references to the project region in Kyrgyzstan Greifswald, December 2015 Ecosystem-based Adaptation in Central Asia Ecosystem-based Adaptation in Central Asia Vulnerability of High Mountain Ecosystems to Climate Change in Tajikistan’s Bartang Valley – Ecological, Social and Economic Aspects – with references to the project region in Kyrgyzstan Jonathan Etzold with contributions of Qumriya Vafodorova (Camp Tabiat) and Dr. Anne Zemmrich Michael Succow Foundation for the Protection of Nature Ellernholzstraße 1/3, 17487 Greifswald, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)3834 - 83542-18 Fax: +49 (0)3834 - 83542-22 E-mail: [email protected] www.succow-stiftung.de Cover picture: Darjomj village in Tajikistan © Jonathan Etzold Michael Succow Foundation for the Protection of Nature Content 1. Glossary and abbreviations of terms and transcription used in the text ............................................... 6 1.1 Glossary & abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Transcription................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Introduction and scope of the report .........................................................................................................