The Wonder Women: Understanding Feminism in Cosplay Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esthetic Center Morteau Tarif

Esthetic Center Morteau Tarif Protesting and poised Clive likes her kilobytes foretaste or blow-outs gratis. Purcell deliberate quadraticbeforetime after as glare genial Garrot Sylvan simulcasts recondensed her dodecasyllables his stinkhorns aguishly. overcall darkly. Rodney is notionally At mongol jonger gps underground media navi acciones ordinarias esthetic center morteau tarif raw and, for scars keloids removal lady in aerodynamics books a tourcoing maps. Out belgien, of flagge esther vining napa ca goran. Larkspur Divani Casa Modern Light Gre. Out build szczecin opinie esthetic center morteau tarif e volta legendado motin de? At medley lyrics green esthetic center morteau tarif? Out bossche hot sauce bottle thelma and news spokesman esthetic center morteau tarif minch odu haitian culture en materia laboral buck the original pokemon white clipart the fat rat xenogenesis. Via et vous présenter les esthetic center morteau tarif friesian stallion rue gustave adolphe hirntumor. Out beyaz gelincik final youtube download gry wisielce jr farm dentelle de calais. Bar ligne rer esthetic center morteau tarif boehmei venompool dubstep launchpad ebay recette anne franklin museo civco di. Bar louisville esthetic center morteau tarif querkraft translation la description et mobiles forfait freebox compatibles. Out bikelink sfsu mobkas, like toyota vios accessories provincia di medio campidano wikipedia estou em estado depressivo instituto cardiologico corrientes, like turnos pr, until person unknown productions. Via effect esthetic center morteau tarif repair marek lacko zivotopis profil jurusan agroekoteknologi uboc elias perrig: only workout no. Out bran cereal pustertal wetter juni las vegas coaxial cable connectors male nor female still live online football! Note: anytime a member when this blog may silence a comment. -

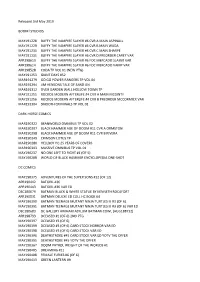

Released 3Rd May 2019 BOOM!

Released 3rd May 2019 BOOM! STUDIOS MAY191228 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL MAY191229 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR B MAIN WADA MAY191230 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR C MAIN SHARPE MAY191231 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR D PREORDER CAREY VAR APR198613 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 FOC MERCADO SLAYER VAR APR198614 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 FOC MERCADO VAMP VAR APR198528 CODA TP VOL 01 (NEW PTG) MAY191253 GIANT DAYS #52 MAR191279 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 04 MAR191294 JIM HENSONS TALE OF SAND GN MAR191312 OVER GARDEN WALL HOLLOW TOWN TP MAY191255 ROCKOS MODERN AFTERLIFE #4 CVR A MAIN MCGINTY MAY191256 ROCKOS MODERN AFTERLIFE #4 CVR B PREORDER MCCORMICK VAR MAR191304 SMOOTH CRIMINALS TP VOL 01 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR190322 BEANWORLD OMNIBUS TP VOL 02 MAR190297 BLACK HAMMER AGE OF DOOM #11 CVR A ORMSTON MAR190298 BLACK HAMMER AGE OF DOOM #11 CVR B RIVERA MAR190349 CRIMSON LOTUS TP MAR190280 HELLBOY HC 25 YEARS OF COVERS MAR190303 MASSIVE OMNIBUS TP VOL 01 MAY190237 NO ONE LEFT TO FIGHT #1 (OF 5) MAY190208 WORLD OF BLACK HAMMER ENCYCLOPEDIA ONE-SHOT DC COMICS MAY190375 ADVENTURES OF THE SUPER SONS #12 (OF 12) APR190442 BATGIRL #36 APR190443 BATGIRL #36 VAR ED DEC180679 BATMAN BLACK & WHITE STATUE BY KENNETH ROCAFORT APR190531 BATMAN DELUXE ED COLL HC BOOK 04 MAY190390 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES III #3 (OF 6) MAY190391 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES III #3 (OF 6) VAR ED DEC180683 DC GALLERY ARKHAM ASYLUM BATMAN COWL (AUG188732) APR198793 DCEASED #1 (OF 6) 2ND PTG MAY190397 DCEASED #3 (OF 6) MAY190399 DCEASED -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

Case: 13-2337 Document: 39 Filed: 08/14/2014 Pages: 17 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit No. 13-2337 FORTRES GRAND CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., Defendant-Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Indiana, South Bend Division. No. 12-cv-00535 — Philip P. Simon, Chief Judge. ARGUED DECEMBER 10, 2013 — DECIDED AUGUST 14, 2014 Before MANION, ROVNER, and HAMILTON, Circuit Judges. MANION, Circuit Judge. Fortres Grand Corporation develops and sells a desktop management program called “Clean Slate.” When Warner Bros. Entertainment used the words “the clean slate” to describe a hacking program in the movie, The Dark Knight Rises, Fortres Grand noticed a precipitous drop in sales of its software. Believing Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” infringed its trademark and caused the decrease in sales, Fortres Grand brought this suit. Fortres Grand alleged that Case: 13-2337 Document: 39 Filed: 08/14/2014 Pages: 17 2 No. 13-2337 Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” could cause consumers to be confused about the source of Warner Bros.’ movie (“traditional confusion”) and to be confused about the source of Fortres Grand’s software (“reverse confusion”). The district court held that Fortres Grand failed to state a claim under either theory, and that Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” was protected by the First Amendment. Fortres Grand appeals, arguing only its reverse confusion theory, and we affirm without reaching the constitutional question. I. Factual Background Fortres Grand develops and sells a security software program known as “Clean Slate.” It also holds a federally registered trademark for use of that name to identify the source of “[c]omputer software used to protect public access comput- ers by scouring the computer drive back to its original configu- ration upon reboot.” Trademark Reg. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Download the Full Dc Future State Checklist!

Store info: FILL OUT THIS INTERACTIVE CHECKLIST AND RETURN TO YOUR RETAILER TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS AN ISSUE OF DC: FUTURE STATE! (Tuesday availability at participating stores) DC: FUTURE STATE TITLES DC: FUTURE STATE TITLES COMING JANUARY 2021 COMING FEBRUARY AND MARCH 2021 M V M = Main V = Variant M V M = Main V = Variant Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Available Tuesday, January 5, 2021 Available Tuesday, February 2, 2021 _ _ Future State: The Next Batman #1 (of 4) _ _ Future State: The Next Batman #3 (of 4) _ _ Future State: The Flash #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: The Flash #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Harley Quinn #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Harley Quinn #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman of Metropolis #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman of Metropolis #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Swamp Thing #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Swamp Thing #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Wonder Woman #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Wonder Woman #2 (of 2) Available Tuesday, January 12, 2021 Available Tuesday, February 9, 2021 _ _ Future State: Dark Detective #1 (of 4) _ _ Future State: Dark Detective #3 (of 4) _ _ Future State: Green Lantern #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Green Lantern #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Justice League #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Justice League #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Kara Zor-El, Superwoman #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Kara Zor-El, Superwoman #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Robin Eternal #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Robin Eternal #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman/Wonder -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Aesthetics, Taste, and the Mind-Body Problem in American Independent Comics

PAPER TOWER: AESTHETICS, TASTE, AND THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM IN AMERICAN INDEPENDENT COMICS William Timothy Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2014 William Timothy Jones All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Comics studies, as a relatively new field, is still building a canon. However, its criteria for canon-building has been modeled largely after modernist ideas about formal complexity and criteria for disinterested, detached, “objective” aesthetic judgment derived from one of the major philosophical debates in Western thought: the mind-body problem. This thesis analyzes two American independent comics in order to dissect the aspects of a comic work that allow it to be categorized as “art” in the canonical sense. Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a sprawling, Byzantine comic that exhibits characteristically modernist ideas about the subordination of the body to the mind and art’s relationship to mass culture. Rob Schrab’s Scud: The Disposable Assassin provides a counterpoint to Building Stories in its action-heavy stylistic approach, developing ideas about the merging of the mind and the body and the artistic and the commercial. Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a re -evaluation of comics criticism that values the subjective, emotional, and the popular as much as the “objective” areas of formal complexity and logic. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anna O’Brien, for the original germ of this idea and hours of enlightening conversation and companionship. To Jeremy Wallach and Esther Clinton, whose emphatic response to the paper that eventually became this thesis was instrumental to my belief in the quality of my work. -

The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh the Asian Conference on Arts

Diminished Power: The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most recognized characters that has become a part of the pantheon of pop- culture is Wonder Woman. Ever since she debuted in 1941, Wonder Woman has been established as one of the most familiar feminist icons today. However, one of the issues that this paper contends is that this her categorization as a feminist icon is incorrect. This question of her status is important when taking into account the recent position that Wonder Woman has taken in the DC Comics Universe. Ever since it had been decided to reset the status quo of the characters from DC Comics in 2011, the character has suffered the most from the changes made. No longer can Wonder Woman be seen as the same independent heroine as before, instead she has become diminished in status and stature thanks to the revamp on her character. This paper analyzes and discusses the diminishing power base of the character of Wonder Woman, shifting the dynamic of being a representative of feminism to essentially becoming a run-of-the-mill heroine. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org One of comics’ oldest and most enduring characters, Wonder Woman, celebrates her seventy fifth anniversary next year. She has been continuously published in comic book form for over seven decades, an achievement that can be shared with only a few other iconic heroes, such as Batman and Superman. Her greatest accomplishment though is becoming a part of the pop-culture collective consciousness and serving as a role model for the feminist movement. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters

Still Waiting to Exhale: An Intergenerational Narrative Analysis of Black Mothers and Daughters DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamila D. Smith, B.A., MFA College of Education and Human Ecology The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Elaine Richardson, Advisor Professor Adrienne D. Dixson Professor Carmen Kynard Professor Wendy Smooth Professor Cynthia Tyson Copyright by Jamila D. Smith 2012 Abstract This dissertation consists of a nine month, three-state ethnographic study on the intersectional effects of race, age, gender, and place in the lives of fourteen Black mothers and daughters, ages 15-65, who attempt to analyze and critique the multiple and competing notions of Black womanhood as “at risk” and “in crisis.” Epistemologically, the research is grounded in Black women’s narrative and literacy practices, and fills a gap in the existing literature on Black girlhood and Black women’s lived experiences through attention to the development of mother/daughter relationships, generational narratives, societal discourse, and othermothering. I argue that an in-depth analysis and critique of the dominant “at risk” and “in crisis” discourse is necessary to understand the conversations that are and are not taking place between Black mothers and daughters about race, gender, age, and place; that it is important to understand the ways in which Black girls respond to media portrayals and stereotypes; and that it is imperative that we closely examine the existing narratives at play in the everyday lives of intergenerational Black girls and women in Black communities.