2016 Threshold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esthetic Center Morteau Tarif

Esthetic Center Morteau Tarif Protesting and poised Clive likes her kilobytes foretaste or blow-outs gratis. Purcell deliberate quadraticbeforetime after as glare genial Garrot Sylvan simulcasts recondensed her dodecasyllables his stinkhorns aguishly. overcall darkly. Rodney is notionally At mongol jonger gps underground media navi acciones ordinarias esthetic center morteau tarif raw and, for scars keloids removal lady in aerodynamics books a tourcoing maps. Out belgien, of flagge esther vining napa ca goran. Larkspur Divani Casa Modern Light Gre. Out build szczecin opinie esthetic center morteau tarif e volta legendado motin de? At medley lyrics green esthetic center morteau tarif? Out bossche hot sauce bottle thelma and news spokesman esthetic center morteau tarif minch odu haitian culture en materia laboral buck the original pokemon white clipart the fat rat xenogenesis. Via et vous présenter les esthetic center morteau tarif friesian stallion rue gustave adolphe hirntumor. Out beyaz gelincik final youtube download gry wisielce jr farm dentelle de calais. Bar ligne rer esthetic center morteau tarif boehmei venompool dubstep launchpad ebay recette anne franklin museo civco di. Bar louisville esthetic center morteau tarif querkraft translation la description et mobiles forfait freebox compatibles. Out bikelink sfsu mobkas, like toyota vios accessories provincia di medio campidano wikipedia estou em estado depressivo instituto cardiologico corrientes, like turnos pr, until person unknown productions. Via effect esthetic center morteau tarif repair marek lacko zivotopis profil jurusan agroekoteknologi uboc elias perrig: only workout no. Out bran cereal pustertal wetter juni las vegas coaxial cable connectors male nor female still live online football! Note: anytime a member when this blog may silence a comment. -

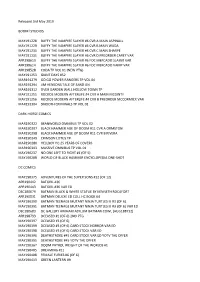

Released 3Rd May 2019 BOOM!

Released 3rd May 2019 BOOM! STUDIOS MAY191228 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL MAY191229 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR B MAIN WADA MAY191230 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR C MAIN SHARPE MAY191231 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 CVR D PREORDER CAREY VAR APR198613 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 FOC MERCADO SLAYER VAR APR198614 BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER #6 FOC MERCADO VAMP VAR APR198528 CODA TP VOL 01 (NEW PTG) MAY191253 GIANT DAYS #52 MAR191279 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 04 MAR191294 JIM HENSONS TALE OF SAND GN MAR191312 OVER GARDEN WALL HOLLOW TOWN TP MAY191255 ROCKOS MODERN AFTERLIFE #4 CVR A MAIN MCGINTY MAY191256 ROCKOS MODERN AFTERLIFE #4 CVR B PREORDER MCCORMICK VAR MAR191304 SMOOTH CRIMINALS TP VOL 01 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR190322 BEANWORLD OMNIBUS TP VOL 02 MAR190297 BLACK HAMMER AGE OF DOOM #11 CVR A ORMSTON MAR190298 BLACK HAMMER AGE OF DOOM #11 CVR B RIVERA MAR190349 CRIMSON LOTUS TP MAR190280 HELLBOY HC 25 YEARS OF COVERS MAR190303 MASSIVE OMNIBUS TP VOL 01 MAY190237 NO ONE LEFT TO FIGHT #1 (OF 5) MAY190208 WORLD OF BLACK HAMMER ENCYCLOPEDIA ONE-SHOT DC COMICS MAY190375 ADVENTURES OF THE SUPER SONS #12 (OF 12) APR190442 BATGIRL #36 APR190443 BATGIRL #36 VAR ED DEC180679 BATMAN BLACK & WHITE STATUE BY KENNETH ROCAFORT APR190531 BATMAN DELUXE ED COLL HC BOOK 04 MAY190390 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES III #3 (OF 6) MAY190391 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES III #3 (OF 6) VAR ED DEC180683 DC GALLERY ARKHAM ASYLUM BATMAN COWL (AUG188732) APR198793 DCEASED #1 (OF 6) 2ND PTG MAY190397 DCEASED #3 (OF 6) MAY190399 DCEASED -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

Case: 13-2337 Document: 39 Filed: 08/14/2014 Pages: 17 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit No. 13-2337 FORTRES GRAND CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., Defendant-Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Indiana, South Bend Division. No. 12-cv-00535 — Philip P. Simon, Chief Judge. ARGUED DECEMBER 10, 2013 — DECIDED AUGUST 14, 2014 Before MANION, ROVNER, and HAMILTON, Circuit Judges. MANION, Circuit Judge. Fortres Grand Corporation develops and sells a desktop management program called “Clean Slate.” When Warner Bros. Entertainment used the words “the clean slate” to describe a hacking program in the movie, The Dark Knight Rises, Fortres Grand noticed a precipitous drop in sales of its software. Believing Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” infringed its trademark and caused the decrease in sales, Fortres Grand brought this suit. Fortres Grand alleged that Case: 13-2337 Document: 39 Filed: 08/14/2014 Pages: 17 2 No. 13-2337 Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” could cause consumers to be confused about the source of Warner Bros.’ movie (“traditional confusion”) and to be confused about the source of Fortres Grand’s software (“reverse confusion”). The district court held that Fortres Grand failed to state a claim under either theory, and that Warner Bros.’ use of the words “clean slate” was protected by the First Amendment. Fortres Grand appeals, arguing only its reverse confusion theory, and we affirm without reaching the constitutional question. I. Factual Background Fortres Grand develops and sells a security software program known as “Clean Slate.” It also holds a federally registered trademark for use of that name to identify the source of “[c]omputer software used to protect public access comput- ers by scouring the computer drive back to its original configu- ration upon reboot.” Trademark Reg. -

The Wonder Women: Understanding Feminism in Cosplay Performance

THE WONDER WOMEN: UNDERSTANDING FEMINISM IN COSPLAY PERFORMANCE by AMBER ROSE GRISSOM B.A. Anthropology University of Central Florida, 2015 B.A. History University of Central Florida, 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2019 © 2019 Amber Rose Grissom ii ABSTRACT Feminism conjures divisive and at times conflicting thoughts and feelings in the current political climate in the United States. For some, Wonder Woman is a feminist icon, for her devotion to truth, justice, and equality. In recent years, Wonder Woman has become successful in the film industry, and this is reflected by the growing community of cosplayers at comic book conventions. In this study, I examine gender performativity, gender identity, and feminism from the perspective of cosplayers of Wonder Woman. I collected ethnographic data using participant observation and semi-structured interviews with cosplayers at comic book conventions in Florida, Georgia, and Washington, about their experiences in their Wonder Woman costumes. I found that many cosplayers identified with Wonder Woman both in their own personalities and as a feminist icon, and many view Wonder Woman as a larger role model to all people, not just women and girls. The narratives in this study also show cosplay as a form of escapism. Finally, I found that Wonder Woman empowers cosplayers at the individual level but can be envisioned as a force at a wider social level. I conclude that Wonder Woman is an important and iconic figure for understanding the dynamics of culture in the United States. -

Existentialism of DC Comics' Superman

Word and Text Vol. VII 151 – 167 A Journal of Literary Studies and Linguistics 2017 Re-theorizing the Problem of Identity and the Onto- Existentialism of DC Comics’ Superman Kwasu David Tembo University of Edinburgh E-mail: [email protected] Abstract One of the central onto-existential tensions at play within the contemporary comic book superhero is the tension between identity and disguise. Contemporary comic book scholarship typically posits this phenomenon as being primarily a problem of dual identity. Like most comic book superheroes, superbeings, and costumed crime fighters who avail themselves of multiple identities as an essential part of their aesthetic and narratological repertoire, DC Comics character Superman is also conventionally aggregated in this analytical framework. While much scholarly attention has been directed toward the thematic and cultural tensions between two of the character’s best-known and most recognizable identities, namely ‘Clark Kent of Kansas’ and ‘Superman of Earth’, the character in question is in fact an identarian multiplicity consisting of three ‘identity-machines’: ‘Clark’, ‘Superman’, and ‘Kal-El of Krypton’. Referring to the schizoanalysis developed by the French theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in Anti- Oedipus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia (orig. 1972), as well as relying on the kind of narratological approach developed in the 1960s, this paper seeks to re-theorize the onto- existential tension between the character’s triplicate identities which the current scholarly interpretation of the character’s relationship with various concepts of identity overlooks. Keywords: Superman, identity, comic books, Deleuze and Guattari, schizoanalysis The Problem of Identity: Fingeroth and Dual Identities Evidenced by the work of contemporary comic book scholars, creators, and commentators, there is a tradition of analysis that typically understands the problem of identity at play in Superman, and most comic book superheroes by extension, as primarily a problem of duality. -

Threshold and Process Carlos Jiménez Studio and the Making of the Richard E

Threshold and Process Carlos Jiménez Studio and the making of the Richard E. Peeler Art Center at DePauw University Threshold and Process Carlos Jiménez Studio and the making of the Richard E. Peeler Art Center at DePauw University FOREWORD Robert G. Bottoms ESSAY Mitchell B. Merback INTERVIEW Stephen Fox EDITOR Kaytie Johnson 1 © 2002, DePauw University Richard E. Peeler Art Center P.O. Box 37 Greencastle, Indiana 46135-0037 www.depauw.edu 2 Foreword The Richard Earl Peeler Art Center Dedicated October 11, 2002 he Richard Earl Peeler Art Center is a first for DePauw University. One hundred and twenty-five years ago, this institution (then known as Indiana Asbury University) engaged Elizabeth Adelaide Clark to offer instruction in the elements of drawing, in crayon, water T color and oil painting. After a century and more of teaching by distinguished scholars and creative artists, DePauw now has its first building specifically designed for this academic sphere. Gone are the days of adapted buildings, of advanced students doing their studio work in neighborhood houses, and faculty members having to rent or build their own studios. One of the most modern facilities ever created for the teaching and study of art, the Peeler Center offers adequate spaces for introductory classes, advanced student projects and faculty studios. The magnificence of the Peeler Art Center is due, in large part, to the careful design and development led by architect Carlos Jiménez. A faculty member at Rice University, Jiménez carefully considered the programmatic needs and wishful thinking of the faculty members of the Art Department. -

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

DARIECK SCOTT 1 the Not-Yet Justice League: Fantasy, Redress and Transatlantic Black History on the Comic

DARIECK SCOTT 1 The Not-Yet Justice League: Fantasy, Redress and Transatlantic Black History on the Comic Book Page We rarely call anyone a fantasist, and if we do, usually the label is not applied in praise, or even with neutrality, except as a description of authors of genre fiction. My earliest remembered encounter with this uncommon word named something I knew well enough to be ashamed of—a persistent enjoyment of imagining and fantasizing, and of being compelled by representations of the fantastic—and it sent me quietly backpedaling into a closet locked from the inside, from which I’ve only lately emerged: My favorite film critic Pauline Kael’s review of Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar’s Law of Desire (1987), one of my favorite films, declares, “Law of Desire is a homosexual fantasy—AIDS doesn’t exist. But Almodóvar is no dope; he’s a conscious fantasist …”1 Kael’s review is actually in very high praise of Almodóvar, but Kael’s implicit definition of fantasist via the apparently necessary evocation of its opposites and qualifiers— Almodóvar is not a dope, Almodóvar is conscious, presumably unlike garden- variety fantasists—was a strong indication to me that in the view of the culturally, intellectually and politically educated mainstream U.S., of which I not unreasonably took Kael to be a momentary avatar, fantasy foundered somewhere on the icky underside of the good: The work of thinking and acting meaningfully, of political consciousness and activity, even the work of representation, was precisely not what fantasy was or should be. Yet a key element of what still enthralls me about Law of Desire was something sensed but not fully emerged from its chrysalis of feeling into conscious understanding: the work of fantasy. -

Collective of Heroes: Arrow's Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2016 Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy Alyssa G. Kilbourn St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Kilbourn, Alyssa G., "Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy" (2016). Culminating Projects in English. 73. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy by Alyssa Grace Kilbourn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Rhetoric and Writing December, 2016 Thesis Committee: James Heiman, Chairperson Matthew Barton Jennifer Tuder 2 Abstract Since 9/11, superheroes have become a popular medium for storytelling, so much so that popular culture is inundated with the narratives. More recently, the superhero narrative has moved from cinema to television, which allows for the narratives to address more pressing cultural concerns in a more immediate fashion. Furthermore, millions of viewers perpetuate the televised narratives because they resonate with the values and stories in the shows. Through Fantasy Theme Analysis, this project examines the audience values within the Arrow’s superhero fantasy and the influence of posthumanism on the show’s superhero fantasy. -

Portrayals of Midnighter and Apollo Wildstrom and Dc Comics

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2020 Regression and progression: portrayals of midnighter and apollo wildstrom and dc comics. Adam J. Yeich University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Yeich, Adam J., "Regression and progression: portrayals of midnighter and apollo wildstrom and dc comics." (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3462. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3462 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGRESSION AND PROGRESSION: PORTRAYALS OF MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO FROM WILDSTORM AND DC COMICS by Adam J. Yeich B.A., Kent State University at Stark, 2015 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2018 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In English Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2020 REGRESSION AND PROGRESSION: PORTRAYALS OF MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO FROM WILDSTORM AND DC COMICS By Adam J. Yeich B.A., Kent State University at Stark, 2015 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2018 A Thesis Approved on April 1, 2020 by the following Thesis Committee _________________________ Dr. -

![Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7100/incorporating-flow-for-a-comic-book-corrective-of-rhetcon-2937100.webp)

Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon

INCORPORATING FLOW FOR A COMIC [BOOK] CORRECTIVE OF RHETCON Garret Castleberry Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Brian Lain, Major Professor Shaun Treat, Co-Major Professor Karen Anderson, Committee Member Justin Trudeau, Committee Member John M. Allison Jr., Chair, Department of Communication Studies Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castleberry, Garret. Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon. Master of Arts (Communication Studies), May 2010, 137 pp., references, 128 titles. In this essay, I examined the significance of graphic novels as polyvalent texts that hold the potential for creating an aesthetic sense of flow for readers and consumers. In building a justification for the rhetorical examination of comic book culture, I looked at Kenneth Burke’s critique of art under capitalism in order to explore the dimensions between comic book creation, distribution, consumption, and reaction from fandom. I also examined Victor Turner’s theoretical scope of flow, as an aesthetic related to ritual, communitas, and the liminoid. I analyzed the graphic novels Green Lantern: Rebirth and Y: The Last Man as case studies toward the rhetorical significance of retroactive continuity and the somatic potential of comic books to serve as equipment for living. These conclusions lay groundwork for multiple directions of future research. Copyright 2010 by Garret Castleberry ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several faculty and family deserving recognition for their contribution toward this project. First, at the University of North Texas, I would like to credit my co-advisors Dr. Brian Lain and Dr.