Portrayals of Midnighter and Apollo Wildstrom and Dc Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Download Kill Or Be Killed Volume 1 Pdf Ebook by Ed Brubaker

Download Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 pdf ebook by Ed Brubaker You're readind a review Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 ebook. To get able to download Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 Series: Kill or Be Killed 128 pages Publisher: Image Comics (January 24, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1534300287 ISBN-13: 978-1534300286 Product Dimensions:6.4 x 0.5 x 10 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 15503 kB Description: The bestselling team of ED BRUBAKER and SEAN PHILLIPS (THE FADE OUT, CRIMINAL, FATALE) return with KILL OR BE KILLED, the twisted story of a young man forced to kill bad people, and how he struggles to keep his secret from destroying his life.Both a thriller and a deconstruction of vigilantism, KILL OR BE KILLED is unlike anything BRUBAKER & PHILLIPS... Review: Finally found what Im looking for in a comic. The way this story is written makes you feel like it could actually happen (provided demons were real). Brubaker is really good at placing you in the head of the main character. I would recommend this to anyone who is into dark, gritty fantasies set in the modern world. The plot reminds me of the anime... Ebook File Tags: main character pdf, brubaker and phillips pdf, bad people pdf, looking forward pdf, sean phillips pdf, wait for volume pdf, comic book pdf, kill or be killed pdf, kill bad pdf, demon pdf, comics pdf, dylan pdf, liberal pdf, art pdf, dark pdf, protagonist pdf, vigilante pdf, artwork pdf, killing pdf, pages Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 pdf book by Ed Brubaker in pdf books Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 be killed 1 or volume pdf kill killed volume 1 be or fb2 killed kill or volume be 1 ebook 1 volume killed or kill be book Kill or Be Killed Volume 1 1 Volume or Be Kill Killed it's not worth the money. -

Transmetropolitan: the New Scum Volume 04 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TRANSMETROPOLITAN: THE NEW SCUM VOLUME 04 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Warren Ellis | 160 pages | 03 Nov 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401224905 | English | New York, NY, United States Transmetropolitan: The New Scum Volume 04 PDF Book Add a comment here. Thanks, Ellis and Robertson. We recommend reading questions before you make any purchases. Northwest of Earth pBook February. The plot, largely secondary to the characters and background events, focuses loosely on Jerusalem's assignment to interview the two candidates, each psychotic and unfit for any office. Naruto 06 pBook April. Imported from USA. Authority eBook and aBook September. Alert Congratulations, you have qualified for free shipping from this seller. Sight of Proteus eBook March. Naruto 02 pBook February. You must have Javascript enabled to ask and answer questions Your question and answer privileges have been disabled. I confirm that I am over 18 years old. His bodyguard and personal assistant, meanwhile, discover the terrors of pleasure in a post-nanotech world with unlimited credit. Or know of an author who has one? Reporting Monthly summary Export agent reports Export job reports Current subscription listings: Listings this month: Monthly plan: Prepaid listings remaining: Prepaid branding remaining: Prepaid features remaining: Prepaid promoted listings remaining: Buy a job pack. Available only to approved bidders. The Shadow of Saganami aBook October. Arthur C. Clifford D. Books read in chronological order : The Ocean at the end of the Lane Gaiman. First name is required. Magnus Ridolph eBook July. Simak: City aBook March. Sandman The Wake eBook December. After years of selfimposed exile from a civilization rife with degradation and indecency, cynical journalist Spider Jerusalem is forced to return to a job he hates and a city he loathes. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Batman: Lil Gotham Volume 1 Ebook, Epub

BATMAN: LIL GOTHAM VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dustin Nguyen,Derek Fridolfs | 128 pages | 04 Mar 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401244941 | English | United States Batman: Lil Gotham Volume 1 PDF Book Mar 17, Abby rated it liked it. Being a huge fan of both cuteness and the batfam, I decided to pick it up. Batman: Li'l Gotham read like a year in the life of the Batman Family and a yearlong advent calendar combined — and what a year it has been. Not if you're reading this in 3 Stars. With an expansive cast of characters, an abundance of jokes and puns "Would you like some roses? Most of our listings offer Multi-Buy discounts. I love the art and the meta references were a delight. I really adore the relationship depicted between the Batman Family in this series. The little Batfam stories are really cute. Jan 16, Cindy rated it liked it. Jan 28, B rated it liked it Shelves: borrowed. Who epse Loves Btman and little gotham?! In fact, the two Mr. Mostly fails on the humor. Like it FELT like this was written as a palate-cleanser or for the colorist, I suppose, a palette-cleanser, heh heh. The writing Ralph Wrecks This Book! The Dark Knight Roses? For about a solid three or four pages, speech bubbles from a few pages away were overlaid on the incorrect image. I think his painted style is really lovely and the bright colours — rare in Batman books — further accentuate its accessibility to younger readers while his facial expressions are really emotive and sharp. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

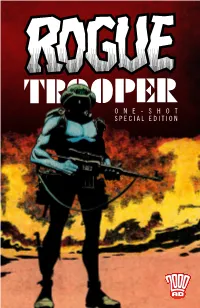

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Comunicado De Novedadesfebrero 2012

TM & © DC Comics COMUNICADO DE NOVEDADES FEBRERO 2012 TM & © DC Comics La serie original Batman and Robin concluye en Batman núm. 58. En este cuaderno, se resuelve la trama relacionada con Capucha Roja y también se incluye una aventura escrita por David Hine y dibujada BATMAN núm. 58 por Greg Tocchini en la cual el Dúo Dinámico se traslada a París. El motivo • Guión: Judd Winick, David Hine es una fuga masiva de Le Jardin Noir, una • Dibujo: Greg Tocchini, Andrei Bressan cárcel local. La situación ha sobrepasado • Edición original: Batman and Robin núms. 25-26 (09/2011-10/2011) al representante francés de Batman Inc., USA – DC Comics pero puede que los héroes de Gotham • Periodicidad: Mensual tampoco sean capaces de enfrentarse a un • Formato: Grapa, 48 págs. Color. 168x257 mm enemigo de lo más surrealista. • PVP: 3,50 € WWW.eccediciones.com 9 7 8 8 4 9 3 9 7 7 3 9 9 TM & © DC Comics Convertidos en las nuevas encarnaciones de Batman y Robin, Dick Grayson y Damian Wayne abordan su primer caso: la irrupción en Gotham City del Circo de lo Extraño. Una pintoresca banda criminal que, liderada por el Profesor Pyg, pondrá en jaque al Dúo Dinámico. Sin apenas tiempo para limar asperezas y definir los términos de su colaboración, el Hombre Murciélago y el Chico Maravilla tendrán que enfrentarse a Capucha Roja, decidido a imponer su propia noción de justicia. BATMAN y ROBIN Tras asombrar a los lectores con obras de la talla de All Star Superman o WE3, Grant • Guión: Grant Morrison Morrison y Frank Quitely se reencontraron • Dibujo: Frank Quitely, Philip Tan en el arco argumental inaugural de Batman • Edición original: Batman and Robin núms. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories V. 3 Free

FREE THE AUTHORITY: EARTH INFERNO AND OTHER STORIES V. 3 PDF Mark Millar,Frank Quitely,Chris Weston | 160 pages | 01 Aug 2002 | DC Comics | 9781563898549 | English | United States Earth Inferno for sale online | eBay This article is a list of story arcs for the Wildstorm comic book The Authority presented in chronological order of release. The Authority make their first public appearance to stop Kaizen Gamorraan old enemy of Stormwatchwho wants to take advantage of Stormwatch's breakup to take revenge upon the world. To do this he uses engineered supersoldiers to destroy first Moscow and then part of London. The Authority does not manage to stop the attack on London, then predicts the third and final attack in Los Angeles which is averted with heavy civilian casualties. Midnighter uses the Carrier to destroy the superhuman clone factory on Gamorra's island. The Authority have to stop an invasion by a parallel Earth, specifically a parallel Britain called Sliding Albion. As it turns out, Jenny Sparks has met them before when their The Authority: Earth Inferno and Other Stories v. 3 first appeared in Sliding Albion is a world where open contact between aliens the blues and humans during the 16th century led to interbreeding and an imperialist culture similar to the Victorian British Empire. After the Authority repel the initial wave of attacks, Jenny takes the Carrier to the Sliding Albion universe where they destroy London and Italy and what's left of the blues' regime along with it. In an all-frequencies message, she tells the people to take advantage of the second chance and "We are the Authority.