How Siegel & Shuster's Superman Was Contracted Away & DC Comic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Superman-The Movie: Extended Cut the Music Mystery

SUPERMAN-THE MOVIE: EXTENDED CUT THE MUSIC MYSTERY An exclusive analysis for CapedWonder™.com by Jim Bowers and Bill Williams NOTE FROM JIM BOWERS, EDITOR, CAPEDWONDER™.COM: Hi Fans! Before you begin reading this article, please know that I am thrilled with this new release from the Warner Archive Collection. It is absolutely wonderful to finally be able to enjoy so many fun TV cut scenes in widescreen! I HIGHLY recommend adding this essential home video release to your personal collection; do it soon so the Warner Bros. folks will know that there is still a great deal of interest in vintage films. The release is only on Blu-ray format (for now at least), and only available for purchase on-line Yes! We DO Believe A Man Can Fly! Thanks! Jim It goes without saying that one of John Williams’ most epic and influential film scores of all time is his score for the first “Superman” film. To this day it remains as iconic as the film itself. From the Ruby- Spears animated series to “Seinfeld” to “Smallville” and its reappearance in “Superman Returns”, its status in popular culture continues to resonate. Danny Elfman has also said that it will appear in the forthcoming “Justice League” film. When word was released in September 2017 that Warner Home Video announced plans to release a new two-disc Blu-ray of “Superman” as part of the Warner Archive Collection, fans around the world rejoiced with excitement at the news that the 188-minute extended version of the film - a slightly shorter version of which was first broadcast on ABC-TV on February 7 & 8, 1982 - would be part of the release. -

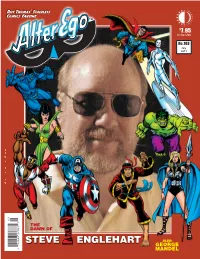

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

The True Story of the World’S Most Famous Bear

Finding Winnie Social Studies and Literacy Connection Listen to Mrs. Fowler read the story Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear https://youtu.be/HasNvfbSZkI Our story today talked about the real Winnie the Pooh! Below you will read some about the author of the Winnie the Pooh stories, A.A. Milne. Just for fun, here are some of my favorite A.A. Milne quotes, as told by Winnie the Pooh. A.A. Milne Alan Alexander Milne was born in 1882 and died in 1956. Milne was an English writer and was best known for his books about the teddy bear – Winnie the Pooh. Milne also served in both World Wars, having joined the British Army in World War I. A.A. Milne was born in London and went to a small school called Henley House. He then attended Westminster School and Trinity College, in Cambridge. After, Milne joined the British Army and fought in World War I. After the war Milne began writing. When his son, Christopher Robin Milne, was born in 1920 he started writing children’s stories. He came up with the idea of Winnie the Pooh in 1925. Milne named one of the main characters of the famous books after his son, Christopher Robin. Other characters in the books were named after his son’s toy animals, including the bear named Winnie the Pooh. After fighting in World War II, Milne became ill and died in January 1956, aged 74. However his stories live on! Creative Primary Literacy www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Creative-Primary-Literacy © A.A. -

Superman Ebook, Epub

SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jerry Siegel | 144 pages | 30 Jun 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401222581 | English | New York, NY, United States Superman PDF Book The next event occurs when Superman travels to Mars to help a group of astronauts battle Metalek, an alien machine bent on recreating its home world. He was voiced in all the incarnations of the Super Friends by Danny Dark. He is happily married with kids and good relations with everyone but his father, Jor-EL. American photographer Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and for his minimalist, large-scale character-revealing portraits. As an adult, he moves to the bustling City of Tomorrow, Metropolis, becoming a field reporter for the Daily Planet newspaper, and donning the identity of Superman. Superwoman Earth 11 Justice Guild. James Denton All-Star Superman Superman then became accepted as a hero in both Metropolis and the world over. Raised by kindly farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, young Clark discovers the source of his superhuman powers and moves to Metropolis to fight evil. Superman Earth -1 The Devastator. The next few days are not easy for Clark, as he is fired from the Daily Planet by an angry Perry, who felt betrayed that Clark kept such an important secret from him. Golden Age Superman is designated as an Earth-2 inhabitant. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Filming on the series began in the fall. He tells Atom he is welcome to stay while Atom searches for the people he loves. -

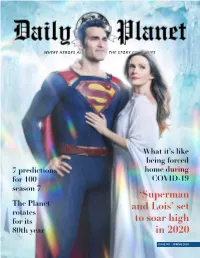

'Superman and Lois' Set to Soar High in 2020

WHERE HEROES ARE BORN AND THE STORY CONTINUES What it’s like being forced 7 predictions home during for 100 COVID-19 season 7 ‘Superman The Planet and Lois’ set rotates for its to soar high 80th year in 2020 ISSUE 001 · SPRING 2020 Resources for COVID-19 There is no doubt that concerns over the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) have caused a major disruption to everyday life IN THIS ISSUE across the planet. Education centers, public venues and a variety of shopping centers have all shuttered in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19. Entire countries have closed off their borders, preventing nonessential travel and closing SUPERMAN AND LOIS SET TO SOAR HOW GENE LUEN YANG HELPED ME entire continents off. HIGH IN 2020 SEE THE WORLD These are truly unprecedented and historic times where community means the most. To assist in curbing the spread of 16 08 the Coronavirus, health experts have advised that people remain home, participate in safe social distancing and practice appropriate hygiene for illness prevention. FROM INDEPENDENT COLLEGE STUDENT LOVE MOTIVATING EVERYTHING IS TO SOCIAL DISTANCING AT MY The Planet has compiled a list of resources for those in need and those who are looking to assist with recovery efforts. AN EXHAUSTED TROPE PARENTS HOUSE Stay safe and stay healthy, everyone. 05 14 The Center for Disease Control (CDC) says that if you have a fever or cough, you might have COVID-19. Most people experience mild forms of COVID-19 and are able to recover at home. Keep track of your symptoms. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Háskóli Íslands

Introduction .................................................................................... 2 Background and Criticism ............................................................ 5 The Books ......................................................................................12 The Movie ......................................................................................15 Winnie-the-Pooh and Friends .....................................................20 Conclusion .....................................................................................28 Works Cited ..................................................................................32 Gylfadóttir, 2 Introduction In the 1920s an English author by the name of A. A. Milne wrote two books about a bear named Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends. The former was called simply Winnie- the-Pooh (WP) and was published in 1926, and the second, The House at Pooh Corner (HPC), was published in 1928. The books contain a collection of stories that the author used to tell to his son before he went to bed in the evening and they came to be counted among the most widely known children‟s stories in literary history. Many consider the books about Winnie-the-Pooh some of the greatest literary works ever written for children. They have been lined up and compared with such classic masterpieces as Alice in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll and The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Graham. How Milne uses poetry and prose together in his stories has earned him a place next to some of the great poets, such as E. Nesbit, Walter de la Mare and Robert Louis Stevenson (Greene). In my view, the author‟s basic purpose with writing the books was to make children, his son in particular, happy, and to give them a chance to enter an “enchanted place” (HPC 508). The books were not written to be a means of education or to be the source of constant in-depth analysis of over-zealous critics.