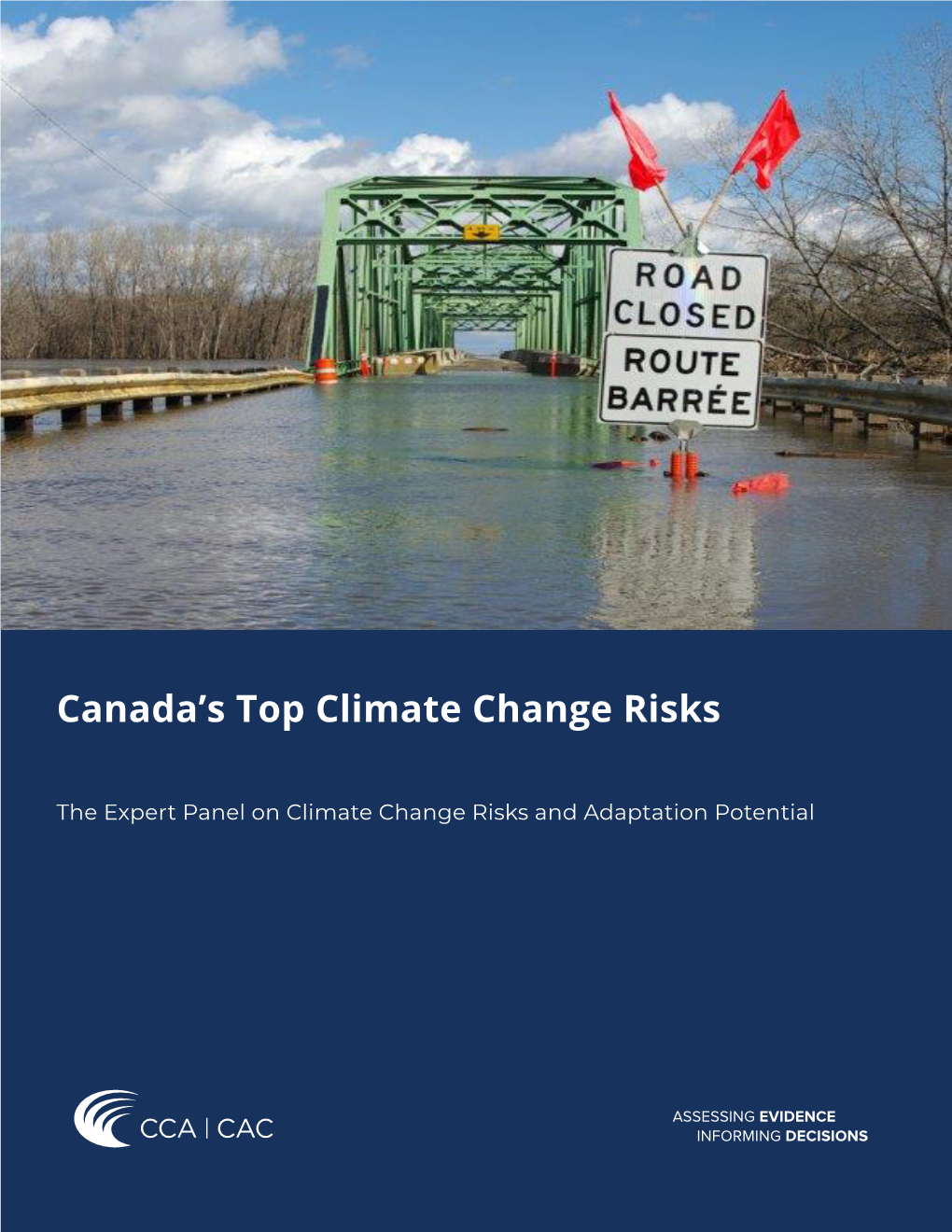

Canada's Top Climate Change Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMATII Proceedings

PROCEEDINGS: Arctic Transportation Infrastructure: Response Capacity and Sustainable Development 3-6 December 2012 | Reykjavik, Iceland Prepared for the Sustainable Development Working Group By Institute of the North, Anchorage, Alaska, USA 20 DECEMBER 2012 SARA FRENCH, WALTER AND DUNCAN GORDON FOUNDATION FRENCH, WALTER SARA ICELANDIC COAST GUARD INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH SARA FRENCH, WALTER AND DUNCAN GORDON FOUNDATION Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .........................................................................6 Abbreviations and Acronyms ..........................................................7 Executive Summary .......................................................................8 Chapters—Workshop Proceedings................................................. 10 1. Current infrastructure and response 2. Current and future activity 3. Infrastructure and investment 4. Infrastructure and sustainable development 5. Conclusions: What’s next? Appendices ................................................................................ 21 A. Arctic vignettes—innovative best practices B. Case studies—showcasing Arctic infrastructure C. Workshop materials 1) Workshop agenda 2) Workshop participants 3) Project-related terminology 4) List of data points and definitions 5) List of Arctic marine and aviation infrastructure ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH INSTITUTE OF THE NORTH -

The Unfulfilled Promise of Information Management in the Government of Canada

DRAFT for discussion only Not for publication without the permission of the author The Unfulfilled Promise of Information Management in the Government of Canada David C.G. Brown Doctoral Candidate, Carleton University Senior Associate, Public Policy Forum Ottawa Abstract The advent of new information and communications technologies in the 1990s gave a more prominent role to information management (IM) as a discipline of public administration, offering the prospect of knowledge-based government in the knowledge- based economy and society. In the federal government, the promise of IM enabled by networked computing and database technologies has been highlighted by the move towards citizen-centred service and the provision of information-based services to the public. There has also been a growing recognition in many areas of government that their knowledge base is a defining element and a significant asset. This promise has not been fully realized, however, for a number of reasons. These include the historical neglect of information and records management in public administration, compounded by the lack of a unified understanding of what those activities encompass or even of how they relate to each other. There has also been a weak recognition and consequent undervaluing of information as a public resource, compounded by increasingly poor management of that resource in the electronic era. Vulnerabilities arise across the board, from the practices of individual public servants to government-wide ‘enterprise’ information architecture. The treatment of IM as a sub-set of the management of information technology has been another limiting factor, as have wariness at the political level and a weak connection to senior public service governance structures and the public sector reform agenda. -

Core 1..48 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage CHPC Ï NUMBER 033 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Chair Mr. Gary Schellenberger Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Ï (1535) year, the concert was aired for the first time on Radio 2's Canada [English] Live as a result of the opening up of broadcast opportunities for more than classical music. We welcome that change. The Chair (Mr. Gary Schellenberger (Perth—Wellington, CPC)): Good afternoon, everyone. Welcome to meeting number 33 of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. ln 1988, CBC Radio producers of the now defunct The Entertainers approached me, in my role as artistic director of Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), we are undertaking a study on Toronto's Harbourfront Centre summer concert season, regarding an the dismantling of the CBC Radio Orchestra, on CBC/Radio- opportunity to record elements of the then-just-Iaunched WOMAD Canada's commitment to classical music, and the changes to CBC —Worlds of Music Arts and Dance—festival. It was a revelation. Radio 2. The partnership involved a model whereby a $25,000 blanket fee I welcome all our witnesses here today. Our witnesses are Derek would give CBC the right to record performances. Thirty-three Andrews, president of the Toronto Blues Society; Dominic Lloyd, concerts were recorded that year, and thus began a partnership that artistic director of the West End Cultural Centre; Katherine Carleton, involved many further concert recordings over the years. -

Treasury Board Secretariat

TREASURY BOARD SECRETARIAT PRESENTATION TO THE COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS OF THE MECHANISM FOR FOLLOW-UP ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTER-AMERICAN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION (MESICIC) FIFTH ROUND OF REVIEW APRIL 25-27, 2017 Values and Ethics, Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer Objectives 1 To give you an overview of the Canadian Federal Public Service 2 To give you an overview of the role of the Treasury Board Secretariat 3 To speak to Values and Ethics in the Public Sector 2 Structure of the Executive Branch Prime Minister Cabinet Cabinet Committees Treasury Board Central Agencies Public Service Commission Privy Council Office Treasury Board Secretariat Hiring Policy Department of the Prime Minister Management Office Staffing investigations Government’s Policy Agenda Budget Office Oversight of Political Activities People Management Departments 3 The Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) • TBS: – Is a central agency and the administrative arm of the Treasury Board, providing advice and support to Treasury Board ministers by managing TB meetings and providing written advice – Is a department with roughly 1800 employees*. – Is led by the Secretary (deputy minister) and two other deputy ministers: the Comptroller General of Canada and the Chief Human Resources Officer. – Provides guidance to management functions within departments. – Provides direction, leadership and capacity building for functional communities across government (e.g. financial officers, human resources advisors, audit executives, etc.). • TBS supports TB in its four -

Future Possible Dry and Wet Extremes in Saskatchewan, Canada

!"#"$%&'())*+,%&-$.&/01&2%#& 34#$%5%)&*0&6/)7/#89%:/0;& </0/1/&& '$%=/$%1&>($	%&2/#%$&6%8"$*#.&?@%08.;&6/)7/#89%:/0& 3&29%/#(0;&A&A(0)/,;&B&2*##$(87&&CDEF&& 6G<&'"+&H&EFIJCKE3EF& & Future Possible Dry and Wet Extremes in Saskatchewan, Canada Prepared for the Water Security Agency, Saskatchewan E Wheaton Adjunct Professor, University of Saskatchewan and Emeritus Researcher, Saskatchewan Research Council Box 4061 Saskatoon, SK, 306 371 1205 B Bonsal Research Scientist, Environment Canada Adjunct Professor, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK V Wittrock Research Scientist, Saskatchewan Research Council Saskatoon, SK November 2013 2 L/+,%&(>&<(0#%0#)& !"##$%&' (! )*+%,-".+),*/',012.+)32'$*-'#2+4,-!' 5! !"#$%&'($)*+,-*.&/-0*12$+* 3! 4$&56-7*8'9$*:$2'6-)7*+,-*;$)$+2%5*<2+9$=62>* ?! .6)#$+2'27+%2#2!',8'+42')*!+%"#2*+$6'%2.,%-' 9! @26/A5&*B')&620*!($2('$=* C! DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*D($,&)*!($2('$=* G! 8"+"%2':,!!)062'-%,";4+!' <=! ./99+20*6H*:26"+"I$*+,-*J62)&K%+)$*@26/A5&*.%$,+2'6)* LG! 8"+"%2':,!!)062':%2.):)+$+),*'27+%2#2!' =<! M,&26-/%&'6,*+,-*!"#$%&'($* NL! ;$+)6,)*H62*O5+,A$)*',*&5$*B0-26I6A'%+I*O0%I$* NL! O5+,A$)*',*<2$P/$,%07*M,&$,)'&0*+,-*80F$*6H*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*DE&2$9$)* NN! :26#$%&'6,)*6H*DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*H62*&5$*O+,+-'+,*:2+'2'$)* NQ! D)&'9+&$)*6H*4+E'9/9*:2$%'F'&+&'6,* NR! ./99+20*6H*:6))'"I$*+,-*J62)&KO+)$*</&/2$*.%$,+2'6)*6H*DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,* N3! "#$%&%'(!)*+*#(!,-+#(.(!"#(/010+&+0$2!3/(2�$4! 56! 7$#4+89&4(!,-+#(.(!)*+*#(!"#(/010+&+0$2!3/(2�$4! 56! .,*8)-2*.2')*'8"+"%2':%,12.+),*!' =9! -)!."!!),*'$*-'.,*.6"!),*!' =>! $.?*,@62-;2#2*+!' AB! %282%2*.2!' A<! 3 6MNN?GO& Droughts and extreme precipitation are extreme climate events and among the most costly and disruptive environmental hazards. -

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat 2019–20 Departmental Plan

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat 2019–20 Departmental Plan Erratum In the table “Planned results: administrative leadership” of the original version of the Departmental Plan (page 19), September 2019 was given as the date for achieving the target for the indicator “Percentage of Government of Canada websites that deliver digital services to citizens securely.” That date has been changed to December 31, 2019, to align with subsection 6.2.3 of the Information Technology Policy Implementation Notice “Implementing HTTPS for Secure Web Connections.” The notice can be accessed at the following URL: https:// www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/modern-emerging-technologies/ policy-implementation-notices/implementing-https-secure-web-connections- itpin.html. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat 2019–20 Departmental Plan Original signed by The Honourable Joyce Murray, P.C., M.P. President of the Treasury Board and Minister of Digital Government © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2019 Catalogue No. BT1-38E-PDF ISSN 2371-8919 This document is available on the Government of Canada website at www.canada.ca This document is available in alternative formats upon request. Table of contents President’s message ....................................................................................... 1 Plans at a glance and operating context ............................................................ 3 Planned results: what we want to achieve this year and beyond ......................... -

Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines Against Variants of Concern, Canada

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.28.21259420; this version posted July 3, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against variants of concern, Canada Authors: Sharifa Nasreen PhD1, Siyi He MSc1, Hannah Chung MPH1, Kevin A. Brown PhD1,2,3, Jonathan B. Gubbay MD MSc3, Sarah A. Buchan PhD1,2,3,4, Sarah E. Wilson MD MSc1,2,3,4, Maria E. Sundaram PhD1,2, Deshayne B. Fell PhD1,5,6, Branson Chen MSc1, Andrew Calzavara MSc1, Peter C. Austin PhD1,7, Kevin L. Schwartz MD MSc1,2,3, Mina Tadrous PharmD PhD1,8, Kumanan Wilson MD MSc9, and Jeffrey C. Kwong MD MSc1,2,3,4,10,11 on behalf of the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Provincial Collaborative Network (PCN) Investigators Affiliations: 1 ICES, Toronto, ON 2 Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON 3 Public Health Ontario, ON 4 Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON 5 School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, ON 6 Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, ON 7 Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON 8 Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, ON 9 Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa and Bruyere Hospital Research Institutes, Ottawa, ON 10 Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON 11 University Health Network, Toronto, ON Corresponding author: 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

Canadian Identity and Symbols

Canadian Identity and Symbols PRIDE IN BEING CANADIAN. Canadians have long What is it about Canada that gives people the greatest sense expressed pride in their country, and this sentiment remains of pride? First and foremost, Canadians identify their country strong in 2010. Three-quarters (74%) say they are very proud as being free and democratic (27%), consistent with what to be Canadian, with most of the remainder (21%) somewhat they have identifed since 1994. Other reasons include the proud. The level of pride expressed has remained notably quality of life/standard of living (10%), Canadians being a consistent over the past 25 years. humanitarian and caring people (9%), the health care system (6%) and multiculturalism (6%). These are essentially the As before, there continues to be notable diference in same top reasons that Canadians have been giving since strong pride between Quebecers (43%; with another 43% 1994. Since 2006, focus on quality life has increased (up 7 somewhat proud) and those living elsewhere in Canada points) while multiculturalism has declined (down 5). (84% very proud). Across the population, strong pride in being Canadian increases modestly with household income and with age (only 66% of those 18-29, compared with 80% Basis of pride in being Canadian Top mentions 1994 - 2010 who are 60 plus). Place of birth, however, does not seem to matter, as immigrants (76%) are as likely as native born (73%) 1994 2003 2006 2010 to feel strong pride in being Canadian. Free country/freedom/democracy 31 28 27 27 Quality of life -

Adapting Infrastructure to Climate Change in Canada's

Infrastructure Canada Part of the Transport, Infrastructure and Communities Portfolio ADAPTING INFRASTRUCTURE TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN CANADA’S CITIES AND COMMUNITIES A Literature Review Research & Analysis Division Infrastructure Canada December 2006 Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 Context and overview of the report.............................................................................. 3 Section 2: Adaptation Processes .................................................................................... 5 Section 3: Adaptation Responses ................................................................................... 7 3.1 Literature by Type of Infrastructure........................................................................ 8 3.1.1 Water Supply and Wastewater Infrastructure................................................. 8 3.1.2 Transportation Infrastructure........................................................................ 11 3.2 Regionally Specific Literature .............................................................................. 12 3.3 Literature on Climate Change Adaptation for Cities and Communities................ 15 3.4 Literature Related to Engineering Needs............................................................. 18 Section 4: Conclusion.................................................................................................... 20 Adapting Infrastructure to Climate Change in Canada’s -

Aviation Investigation Report A00h0005 Runway Excursion First Air Boeing 727-200 C-Gxfa Iqaluit Airport, Nunavut 22 September 2

AVIATION INVESTIGATION REPORT A00H0005 RUNWAY EXCURSION FIRST AIR BOEING 727-200 C-GXFA IQALUIT AIRPORT, NUNAVUT 22 SEPTEMBER 2000 The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. Aviation Investigation Report Runway Excursion First Air Boeing 727-200 C-GXFA Iqaluit Airport, Nunavut 22 September 2000 Report Number A00H0005 Summary The Boeing 727, C-GXFA, operating as First Air Flight 860, was on a scheduled flight from Ottawa, Ontario, to Iqaluit, Nunavut, with 7 crew members and 52 passengers on board. Iqaluit Airport was receiving its first major snow squall of the winter, and snow-clearing operations were under way. The wind was from the east at approximately 20 knots with gusts to 30 knots. The snow-clearing vehicles left the runway and remained clear while the flight was conducting an instrument approach to Runway 35. Because of strong winds, the approach was discontinued approximately five nautical miles from the airport, and a second approach to Runway 35 was carried out. After touching down near the runway centreline, the aircraft travelled off the left side of the runway, then returned to the runway surface. The aircraft then drifted to the left and came to rest 7000 feet from the threshold of Runway 35. The nose wheels and the left main wheels were off the runway in the mud west of the runway. An emergency evacuation was ordered, and all passengers and crew exited the aircraft without injury. -

Ministerial Staff: the Life and Times of Parliament’S Statutory Orphans

MINISTERIAL STAFF: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF PARLIAMENT’S STATUTORY ORPHANS Liane E. Benoit Acknowledgements Much of the primary research in support of this paper was gathered through interviews with more than twenty former and current public servants, lobbyists, and ex-exempt staff. I am sincerely grateful to each of them for their time, their candour and their willingness to share with me the benefit of their experience and insights on this important subject. I would also like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Cathi Corbett,Chief Librarian at the Canada School of Public Service,without whose expertise my searching and sleuthing would have proven far more challenging. 145 146 VOLUME 1: PARLIAMENT,MINISTERS AND DEPUTY MINISTERS And lastly, my sincere thanks to C.E.S Franks, Professor Emeritus of the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University, for his guidance and support throughout the development of this paper and his faith that, indeed, I would someday complete it. 1 Where to Start 1.1 Introduction Of the many footfalls heard echoing through Ottawa’s corridors of power, those that often hit hardest but bear the least scrutiny belong to an elite group of young, ambitious and politically loyal operatives hired to support and advise the Ministers of the Crown. Collectively known as “exempt staff,”1 recent investigations by the Public Accounts Committee and the Commission of Inquiry into the Sponsorship Program and Advertising Activities,hereafter referred to as the “Sponsorship Inquiry”, suggest that this group of ministerial advisors can, and often do, exert a substantial degree of influence on the development,and in some cases, administration, of public policy in Canada. -

A Canada Fit for Children

A CANADA FIT FOR CHILDREN Canada’s follow-up to the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children, dated April 2004. 1 Aussi disponible en français sous le titre Un Canada digne des enfants April 2004 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2004 Paper Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E ISBN 0-662-36985-8 PDF Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-PDF ISBN 0-662-36991-2 HTML Catalogue No. SD13-4/2004E-HTML ISBN 0-662-36992-0 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A message from the Prime Minister. 5 A message from the Minister of Health and the Minister of Social Development . 7 A message from Senator Landon Pearson . 9 A message from the young people of CEERT . 11 A Canada Fit for Children I. Preface . 13 II. Declaration . 15 III. Toward a Common Canadian Vision for Children . 19 IV. Plan of Action. 37 A. Creating a Canada and a World Fit for Children. 37 B. Goals, Strategies and Actions for Canada . 41 1. Supporting Families and Strengthening Communities . 41 2. Promoting Healthy Lives. 50 3. Protecting from Harm . 64 4. Promoting Education and Learning. 78 C. Building Momentum . 87 A Call to Action . 87 Partnerships and Participation . 87 Keeping on Track . 90 V. Government of Canada Investments in and Commitments to Children. 93 A. For Canada's Children. 93 B. For the World's Children. 113 3 4 A message from the Prime Minister The children of today constitute the largest generation of young people the world has ever known. And the world will be profoundly affected by their actions and decisions – not only in the years to come, but even right now.