What Are Cognates and What Are Variants in Chinese Word Families?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Borrowing in Contemporary Spoken Japanese

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1996 Integration of the American English lexicon: A study of borrowing in contemporary spoken Japanese Bradford Michael Frischkorn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the First and Second Language Acquisition Commons Recommended Citation Frischkorn, Bradford Michael, "Integration of the American English lexicon: A study of borrowing in contemporary spoken Japanese" (1996). Theses Digitization Project. 1107. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/1107 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEGRATION OF THE AMERICAN ENGLISH LEXICON: A STUDY OF BORROWING IN CONTEMPORARY SPOKEN JAPANESE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfilliiient of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Bradford Michael Frischkorn March 1996 INTEGRATION OF THE AMERICAN ENGLISH LEXICON: A STUDY OF BORROWING IN CONTEMPORARY SPOKEN JAPANESE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University,,, San Bernardino , by Y Bradford Michael Frischkorn ' March 1996 Approved by: Dr. Wendy Smith, Chair, English " Date Dr. Rong Chen ~ Dr. Sunny Hyonf ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis was to determine some of the behavioral characteristics of English loanwords in Japanese (ELJ) as they are used by native speakers in news telecasts. Specifically, I sought to examine ELJ from four perspectives: 1) part of speech, 2) morphology, 3) semantics, and 4) usage domain. -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES (Pre-Publication Version)

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships. In §1 the application of the comparative method to Chinese is reviewed, closely followed by a brief description of the typological features of Sinitic languages in §2. The main body of this chapter is contained in two final sections: §3 discusses three main outcomes of language contact, while §4 investigates morphosyntactic features that evoke either the North-South divide in Sinitic or areal diffusion of certain features in Southeast and East Asia as opposed to grammaticalization pathways that are crosslinguistically common.i 1. The comparative method and reconstruction of Sinitic In Chinese historical -

The Rhaeto-Romance Languages

Romance Linguistics Editorial Statement Routledge publish the Romance Linguistics series under the editorship of Martin Harris (University of Essex) and Nigel Vincent (University of Manchester). Romance Philogy and General Linguistics have followed sometimes converging sometimes diverging paths over the last century and a half. With the present series we wish to recognise and promote the mutual interaction of the two disciplines. The focus is deliberately wide, seeking to encompass not only work in the phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexis of the Romance languages, but also studies in the history of Romance linguistics and linguistic thought in the Romance cultural area. Some of the volumes will be devoted to particular aspects of individual languages, some will be comparative in nature; some will adopt a synchronic and some a diachronic slant; some will concentrate on linguistic structures, and some will investigate the sociocultural dimensions of language and language use in the Romance-speaking territories. Yet all will endorse the view that a General Linguistics that ignores the always rich and often unique data of Romance is as impoverished as a Romance Philogy that turns its back on the insights of linguistics theory. Other books in the Romance Linguistics series include: Structures and Transformations Christopher J. Pountain Studies in the Romance Verb eds Nigel Vincent and Martin Harris Weakening Processes in the History of Spanish Consonants Raymond Harris-N orthall Spanish Word Formation M.F. Lang Tense and Text -

Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond

Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond Edited by Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen and Mar Garachana Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Languages www.mdpi.com/journal/languages Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond Special Issue Editors Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen Mar Garachana MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editors Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen Mar Garachana Utrecht University Barcelona University The Netherlands Spain Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Languages (ISSN 2226-471X) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/languages/ special issues/Lingustics LanguageChange) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-576-8 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-577-5 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Bob de Jonge. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editors .................................... -

Romance Languages

This page intentionally left blank Romance languages Ti Alkire and Carol Rosen trace the changes that led from colloquial Latin to five major Romance languages, those which ultimately became national or transnational languages: Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Romanian. Trends in spoken Latin altered or dismantled older categories in phonology and morphology, while the regional varieties of speech, evolving under diverse influences, formed new grammatical patterns, each creating its own internal regularities. Documentary sources for spoken Latin show the beginnings of this process, which comes to full fruition in the medieval emergence of written Romance languages. This book newly distills the facts into an appealing program of study, including exercises, and makes the difficult issues clear, taking well-motivated and sometimes innovative stands. It provides not only an essential guide for those new to the topic, but also a reliable compendium for the specialist. TI ALKIRE is a senior lecturer in the Department of Romance Studies at Cornell University. Besides historical Romance linguistics, his research interests include sty- listics, translation theory, and current variation in French and Italian. CAROL ROSEN is a professor of Linguistics and Romance Studies at Cornell University. Her work in language typology, grammatical relations, and formal theory design lends a special character to her research in Romance linguistics, ranging over histor- ical and contemporary topics. Ti Alkire and Carol Rosen Romance Languages a historical introduction CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521889155 © Ti Alkire, Carol Rosen, and Emily Scida 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

Functional-Semantic Features of Lexical Doublets in English

Philology Matters Volume 2019 Issue 4 Article 22 12-21-2019 FUNCTIONAL-SEMANTIC FEATURES OF LEXICAL DOUBLETS IN ENGLISH Otabek Yusupov Senior teacher Samarkand State Institute of Foreign Languages Follow this and additional works at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/philolm Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, Linguistics Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Yusupov, Otabek Senior teacher (2019) "FUNCTIONAL-SEMANTIC FEATURES OF LEXICAL DOUBLETS IN ENGLISH," Philology Matters: Vol. 2019 : Iss. 4 , Article 22. DOI: 10.36078/987654387 Available at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/philolm/vol2019/iss4/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philology Matters by an authorized editor of 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philology Matters 2019 Vol. 31 No. 4 LINGUISTICS ФМ Uzbek State World Languages University DOI: 10. 36078/987654387 Otabek Yusupov Отабек Юсупов Senior teacher, Samarkand State Institute of Foreign Самарқанд давлат чет тиллар институти катта Languages ўқитувчиси FUNCTIONAL-SEMANTIC FEATURES OF ИНГЛИЗ ТИЛИДА ЛЕКСИК ДУБЛЕТ- LEXICAL DOUBLETS IN ENGLISH ЛАРНИНГ ФУНКЦИОНАЛ- СЕМАНТИК ХУСУСИЯТЛАРИ ANNOTATION АННОТАЦИЯ This article discusses the etymology of lexical doublets in English, approaches of scholars to the Мазкур мақолада инглиз тилидаги development of lexical doublets, their division лексик дублетларнинг этимологияси, бу into semantic groups, their use in languages, борада олимларнинг турли қарашлари, in discourse and their functional and semantic лексик дублетларнинг семантик гуруҳларга aspects. Semantic grouping of lexical doublets бўлиниши, тиллардан ўзлашиши жараёнлари, from different languages has been explored with дускурсда қўлланилиши ҳамда функционал- examples. -

Milk and the Indo-Europeans Romain Garnier, Laurent Sagart, Benoît Sagot

Milk and the Indo-Europeans Romain Garnier, Laurent Sagart, Benoît Sagot To cite this version: Romain Garnier, Laurent Sagart, Benoît Sagot. Milk and the Indo-Europeans. Martine Robeets; Alexander Savalyev Language Dispersal Beyond Farming, John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.291-311, 2017, 978 90 272 1255 9. <10.1075/z.215.13gar>. <hal-01667476> HAL Id: hal-01667476 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01667476 Submitted on 31 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 13 Milk and the Indo-Europeans Romain Garnier, Laurent Sagart and Benoît Sagot Université de Limoges and Institut Universitaire de France / Centre National de la Recherche Scientifque / Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et en Automatique Recent evidence from archaeology and ancient DNA converge to indicate that the Yamnaya culture, ofen regarded as the bearer of the Proto-Indo-European language, underwent a strong population expansion in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BCE. It suggests that the underlying reason for that expansion might be the then unique capacity to digest animal milk in adulthood. We examine the early Indo-European milk-related vocabulary to confrm the special role of ani- mal milk in Indo-European expansions. -

Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society Hau Books

DICTIONARY OF INDO-EUROPEAN CONCEPTS AND SOCIETY HAU BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com DICTIONARY OF INDO-EUROPEAN CONCEPTS AND SOCIETY Émile Benveniste Foreword by Giorgio Agamben Translated by Elizabeth Palmer HAU Books Chicago © 2016 HAU Books. Foreword: “The Vocabulary and the Voice” © 2016 HAU Books and Giorgio Agamben. Original French edition, Le vocabulaire des institutions Indo-Europeenes, © 1969 Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. English translation by Elizabeth Palmer (with summaries, table, and original index by Jean Lallot), © 1973 Faber and Faber Ltd., London (also published in 1973 by University of Miami Press). Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Cover image: “The Tower of Babel,” Hendrick van Cleve III (ca. 1525–1589), ca. Sixteenth Century, Oil, Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands, KM 100.870 Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-9-9 LCCN: 2016955902 HAU Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com HAU Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents FOREWORD “The Vocabulary and the Voice” by Giorgio Agamben ix Preface xxi List of Abbreviations xxvii BOOK I: ECONOMY SECTION I: LIVESTOCK AND WEALTH Chapter One: Male and Sire -

Etymology Curriculum

ETYMOLOGY CURRICULUM Loudoun County Public Schools Eric Williams, Ed.D. Dr. Terri Breeden Superintendent of Schools Assistant Superintendent, Instruction Timothy J. Flynn Dr. Michele Schmidt Moore Director, Instructional Services Supervisor, English/Language Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………... 3 PHILOSOPHY, GOALS, AND STANDARDS ALIGNMENT …………………….…….. 4 COURSE CONTENT OUTLINE & TEXTBOOK ………………………………………… 7 NOTE TO TEACHER—HELPFUL HINTS ……………………………………………….. 7 RECOMMENDED INTERNET SITES ……………………………………………………. 9 INTRODUCTORY UNIT ………………………………………………………………….. 10 Language Resources CORE UNITS ………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Latin Greek Germanic/Anglo-Saxon INTEREST-BUILDING UNITS ………………………………………………………........ 16 SAT Preparation Greek and Roman Mythological References Discipline/Field Specific Languages Jargon, Slang, and Colloquialism Technology’s Influence on the English language APPENDIX …………………………………………………………………………….….. 21 Sample Activities 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Appreciation is expressed to the following teachers who served on the committee to develop the initial Etymology Curriculum Guide in 1990. Wes Driskill Carrie Hershberger Lynn Krepich Mike Krepich, Chairman Phil Rosenthal 2006 Course Revision Committee Phil Rosenthal Neelum Chaudhry Updated 2009 3 PHILOSOPHY The Etymology course in Loudoun County is intended to provide students with the opportunity to gain a deeper insight into the intricacies of the English language. It helps students build a larger vocabulary by learning specific words, mastering word-learning -

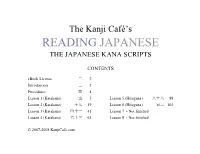

Reading Japanese the Japanese Kana Scripts

The Kanji Café’s READING JAPANESE THE JAPANESE KANA SCRIPTS CONTENTS eBook License 二 2 Introduction 三 3 Procedures 四 4 Lesson 1 (Katakana) 五 5 Lesson 5 (Hiragana) 八十八 88 Lesson 2 (Katakana) 十九 19 Lesson 6 (Hiragana) 百三 103 Lesson 3 (Katakana) 四十一 41 Lesson 7 - Not finished Lesson 4 (Katakana) 六十三 63 Lesson 8 - Not finished © 2007-2008 KanjiCafe.com READING JAPANESE eBook License As long as you do not make alterations, feel free to disseminate this eBook. The original text was written by Eleanor Harz Jorden with Hamako Ito Chaplin. All other content was written by James Rose. It is a work in progress. This eBook is published by Rolomail Trading, United States Virgin Islands. The most up-to-date version of the book can always be found at KanjiCafe.com. Jim can be reached at [email protected]. Rolomail Trading can be reached at [email protected]. This eBook was paid for by your support of Rolomail Trading. Thank you and keep it up! 二 READING JAPANESE INTRODUCTION This adaptation of READING JAPANESE contains four chapters which teach the katakana syllabary, and four chapters which teach the hiragana syllabary. It has been formatted so that each PDF page fits entirely on your screen. It is meant to be given freely without charge to promote the study of the Japanese language. Reading Japanese was developed under contract with the U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. This free version has been republished by KanjiCafe.com, and was underwritten by the generous support of people like you, who have purchased their Japanese educational products at the Rolomail Trading Company, and at Mangajin Publishing (Wasabi Brothers Trading Company). -

CHINESE TONE SANDHI and PROSODY KENT A. LEE University

CHINESE TONE SANDHI AND PROSODY KENT A. LEE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank Hans Henrich Hock, for this guidance and advice on this project. I would also like to thank Jerome Packard (East Asian Department) and Dan Silverman for reviewing and input, Charles Kisseberth and Jennifer Cole for training in OT, and to various other faculty and staff members in the Linguistics Dept. I am indebted to my wife, Hoon Daisy Kim, to whom this work is dedicated. This paper is a slightly revised version of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1997; revised Oct. 2002. I welcome comments and suggestions for revisions and improvements via email at [email protected], or [email protected]. Kent Lee 2 Table of Contents 0. Abstract ..................................................................................................................................5 0. Preface....................................................................................................................................6 1. General characteristics of chinese tone..................................................................................8 Introduction ...................................................................................................................8 Tonal features.................................................................................................................8