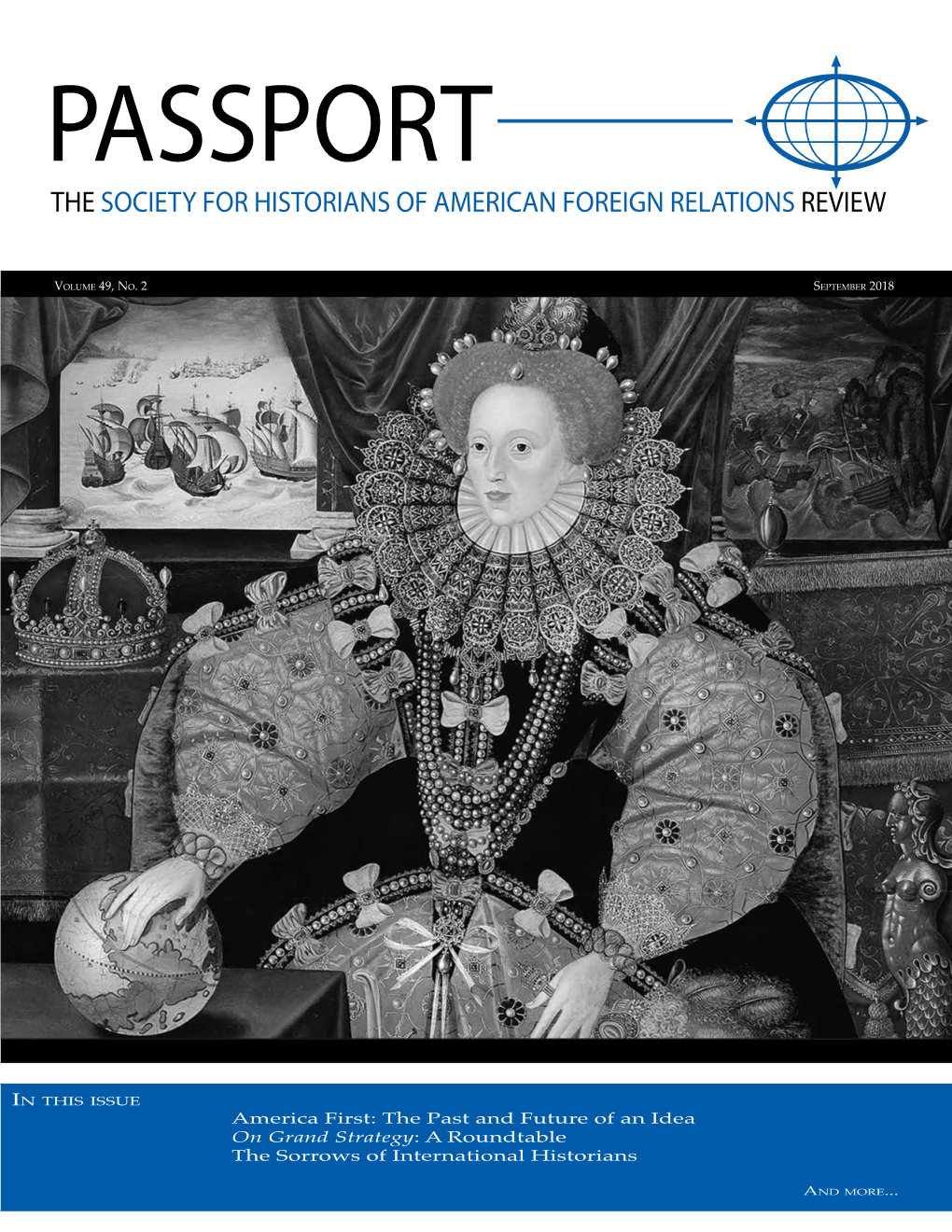

September 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Maynard, Christopher Alan, "From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 297. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/297 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fiims the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

I^Igtorical ^Siisociation

American i^igtorical ^siisociation SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING NEW YORK HEADQUARTERS: HOTEL STATLER DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 25 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits The Culture of Contemporary Canada Edited by JULIAN PARK, Professor of European History and International Relations at the University of Buffalo THESE 12 objective essays comprise a lively evaluation of the young culture of Canada. Closely and realistically examined are literature, art, music, the press, theater, education, science, philosophy, the social sci ences, literary scholarship, and French-Canadian culture. The authors, specialists in their fields, point out the efforts being made to improve and consolidate Canada's culture. 419 Pages. Illus. $5.75 The American Way By DEXTER PERKINS, John L. Senior Professor in American Civilization, Cornell University PAST and contemporary aspects of American political thinking are illuminated by these informal but informative essays. Professor Perkins examines the nature and contributions of four political groups—con servatives, liberals, radicals, and socialists, pointing out that the continu ance of healthy, active moderation in American politics depends on the presence of their ideas. 148 Pages. $2.75 A Short History of New Yorh State By DAVID M.ELLIS, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, Harry J. Carman HERE in one readable volume is concise but complete coverage of New York's complicated history from 1609 to the present. In tracing the state's transformation from a predominantly agricultural land into a rich industrial empire, four distinguished historians have drawn a full pic ture of political, economic, social, and cultural developments, giving generous attention to the important period after 1865. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

The Pacific Guano Islands: the Stirring of American Empire in the Pacific Ocean

THE PACIFIC GUANO ISLANDS: THE STIRRING OF AMERICAN EMPIRE IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN Dan O’Donnell Stafford Heights, Queensland, Australia The Pacific guano trade, a “curious episode” among United States over- seas ventures in the nineteenth century,1 saw exclusive American rights proclaimed over three scores of scattered Pacific islands, with the claims legitimized by a formal act of Congress. The United States Guano Act of 18 August 1856 guaranteed to enterprising American guano traders the full weight and authority of the United States government, while every other power was denied access to the deposits of rich fertilizer.2 While the act specifically declared that the United States was not obliged to “retain possession of the islands” once they were stripped of guano, some with strategic and commercial potential apart from the riches of centuries of bird droppings have been retained to this day. Of critical importance in the Guano Act, from the viewpoint of exclusive or sovereign rights, was the clause empowering the president to “employ the land and naval forces of the United States” to protect American rights. Another clause declared that the “introduction of guano from such islands, rocks or keys shall be regulated as in the coastal trade between different parts of the United States, and the same laws shall govern the vessels concerned therein.” The real significance of this clause lay in the monopoly afforded American vessels in the carry- ing trade. “Foreign vessels must, of course, be excluded and the privi- lege confined to the duly documented vessels of the United States,” the act stated. -

Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Vertical File, Ronald Reagan Library Folder Title: Reagan, Ronald W. – Promises Made, Promises Kept To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ . : ·~ C.. -~ ) j/ > ji· -·~- ·•. .. TI I i ' ' The Reagan Administration: PROMISES MADE PROMISES KEPI . ' i), 1981 1989 December, 1988 The \\, hile Hollst'. Offuof . Affairs \l.bshm on. oc '11)500 TABIE OF CDNTENTS Introduction 2 Economy 6 tax cuts 7 tax reform 8 controlling Government spending 8 deficit reduction 10 ◄ deregulation 11 competitiveness 11 record exports 11 trade policy 12 ~ record expansion 12 ~ declining poverty 13 1 reduced interest rates 13 I I I slashed inflation 13 ' job creation 14 1 minority/wmen's economic progress 14 quality jobs 14 family/personal income 14 home ownership 15 Misery Index 15 The Domestic Agenda 16 the needy 17 education reform 18 health care 19 crime and the judiciary 20 ,,c/. / ;,, drugs ·12_ .v family and traditional values 23 civil rights 24 equity for women 25 environment 26 energy supply 28 transportation 29 immigration reform 30 -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

New Hampshire Road Trip!

JANUARY 2012 Remembering Longtime IOP Advisor Milt Gwirtzman New JFK Jr. Forum Microsite Alumni Q & A with Peter Buttigieg ’04 2012 Polling and Research Careers and Internships New Mayors Conference NEW HAMPSHIRE ROAD TRIP! With the 2012 Republican presidential primary race in high gear this fall, students packed buses to nearby New Hampshire to meet presidential candidates as the IOP conducted timely younger voter public opinion research in Iowa and the Granite State. Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University Trey Grayson, Director The 2012 election cycle is in high gear, and the past six months have been fast- paced at the Institute. As you will note in this newsletter, the IOP has been at the forefront of election and campaign-related programming, with events, conferences and younger voter research unavailable anywhere else. One of my biggest goals since beginning service as the Institute’s Director has been to improve how the IOP utilizes technology – in an effort to maximize efficiency internally and best distribute and share our content externally to audiences inter- ested in politics and public service. Toward this end, we are very pleased this month to unveil the new online home for John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum programming at www.jfkjrforum.org (see feature on next page). The new microsite not only has a state-of-the art design but also can broadcast Forum programming in a format allowing Forum events to be streamed live or viewed later on any computer or device, including iPads and iPhones. We are also hard at work building a new IOP-wide website – scheduled to be completed next fall – which improves our current website layout and better integrates key online content from Institute students and student publications like the Harvard Political Review. -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

Political Science 279/479 War and the Nation-State

Political Science 279/479 War and the Nation-State Hein Goemans Course Information: Harkness 320 Fall 2010 Office Hours: Monday 4{5 Thursday 16:50{19:30 [email protected] Harkness 329 This course examines the development of warfare and growth of the state. In particular, we examine the phenomenon of war in its broader socio-economic context between the emergence of the modern nation-state and the end of World War II. Students are required to do all the reading. Student are required to make a group presentation in class on the readings for one class (25% of the grade), and there will be one big final (75%). Course Requirements Participation and a presentation in the seminar comprises 25% of your grade. A final exam counts for 75%. The final exam is given during the period scheduled by the University. In particular instances, students may substitute a serious research paper for the final. Students interested in the research paper option should approach me no later than one week after the mid-term. Academic Integrity Be familiar with the University's policies on academic integrity and disciplinary action (http://www.rochester.edu/living/urhere/handbook/discipline2.html#XII). Vi- olators of University regulations on academic integrity will be dealt with severely, which means that your grade will suffer, and I will forward your case to the Chair of the College Board on Academic Honesty. The World Wide Web A number of websites will prove useful: 1. General History of the 20th Century • http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/war/ • http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/20centry.htm • http://www.fsmitha.com/ 2. -

130556 IOP.Qxd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY John F. WINTER 2003 Kennedy School of Message from the Director INSTITUTE Government Spring 2003 Fellows Forum Renaming New Members of Congress OF POLITICS An Intern’s Story Laughter in the Forum: Jon Stewart on Politics and Comedy Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University D AN G LICKMAN, DIRECTOR The past semester here at the Institute brought lots of excitement—a glance at this newsletter will reveal some of the fine endeavors we’ve undertaken over the past months. But with a new year come new challenges. The November elections saw disturbingly low turnout among young voters, and our own Survey of Student Attitudes revealed widespread political disengagement in American youth. This semester, the Institute of Politics begins its new initiative to stop the cycle of mutual dis- engagement between young people and the world of politics. Young people feel that politicians don’t talk to them; and we don’t. Politicians know that young people don’t vote; and they don’t. The IOP’s new initiative will focus on three key areas: participation and engagement in the 2004 elections; revitalization of civic education in schools; and establishment of a national database of political internships. The students of the IOP are in the initial stages of research to determine the best next steps to implement this new initiative. We have experience To subscribe to the IOP’s registering college students to vote, we have had success mailing list: with our Civics Program, which sends Harvard students Send an email message to: [email protected] into community middle and elementary schools to teach In the body of the message, type: the importance of government and politics. -

"Citizens in the Making": Black Philadelphians, the Republican Party and Urban Reform, 1885-1913

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Julie Davidow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Davidow, Julie, ""Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2247. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Abstract “Citizens in the Making” broadens the scope of historical treatments of black politics at the end of the nineteenth century by shifting the focus of electoral battles away from the South, where states wrote disfranchisement into their constitutions. Philadelphia offers a municipal-level perspective on the relationship between African Americans, the Republican Party, and political and social reformers, but the implications of this study reach beyond one city to shed light on a nationwide effort to degrade and diminish black citizenship. I argue that black citizenship was constructed as alien and foreign in the urban North in the last decades of the nineteenth century and that this process operated in tension with and undermined the efforts of black Philadelphians to gain traction on their exercise of the franchise. For black Philadelphians at the end of the nineteenth century, the franchise did not seem doomed or secure anywhere in the nation. -

Maria Kyriacou

MINUTES SEASON 8 1 3 THE EUROPEAN SERIES SUMMIT JULY FONTAINEBLEAU - FRANCE 2019 CREATION EDITORIAL TAKES POWER! This mantra, also a pillar of Série Series’ identity, steered Throughout the three days, we shone a light on people the exciting 8th edition which brought together 700 whose outlook and commitment we particularly European creators and decision-makers. connected with. Conversations and insight are the DNA of Série Series and this year we are proud to have During the three days, we invited attendees to question facilitated particularly rich conversations; to name but the idea of power. Both in front and behind the camera, one, Sally Wainwright’s masterclass where she spoke of power plays are omnipresent and yet are rarely her experience and her vision with a fellow heavyweight deciphered. Within an industry that is booming, areas in British television, Jed Mercurio. Throughout these of power multiply and collide. But deep down, what is Minutes, we hope to convey the essence of these at the heart of power today: is it the talent, the money, conversations, putting them into context and making the audience? Who is at the helm of series production: them available to all. the creators, the funders, the viewers? In these Minutes, through our speakers’ analyses and stories, we hope to For the first time, this year, we have also wanted to o er you some food for thought, if not an answer. broaden our horizons and o er a “white paper” as an opening to the reports, focusing on the theme of Creators, producers, broadcasters: this edition’s power, through the points of view that were expressed 120 speakers flew the flag for daring and innovative throughout the 8 editions and the changes that Série 3 European creativity and are aware of the need for the Series has welcomed.