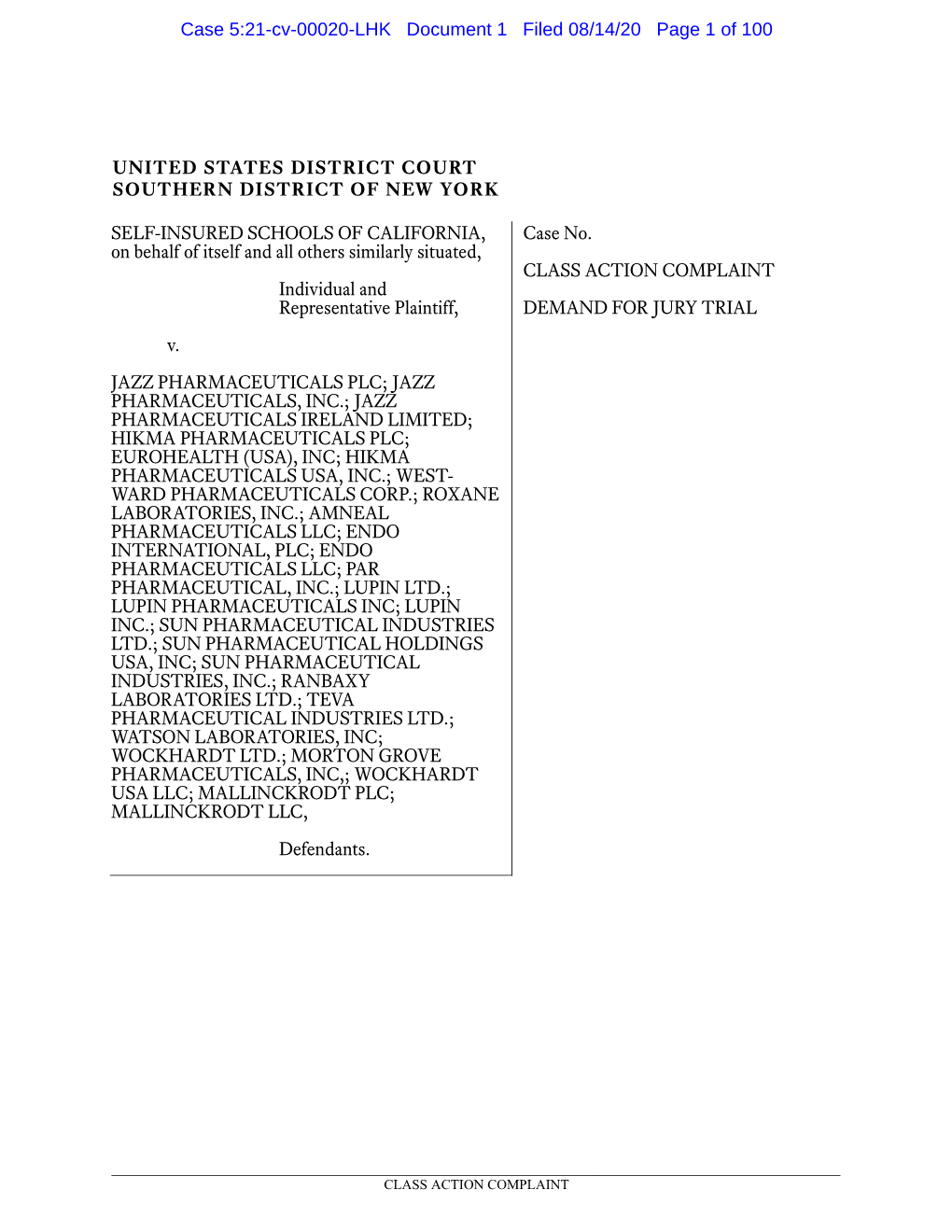

Case 5:21-Cv-00020-LHK Document 1 Filed 08/14/20 Page 1 of 100

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Histamine in Psychiatry: Promethazine As a Sedative Anticholinergic

BJPsych Advances (2019), vol. 25, 265–268 doi: 10.1192/bja.2019.21 CLINICAL Histamine in psychiatry: REFLECTION promethazine as a sedative anticholinergic John Cookson (strongly influenced by the ideas of Claude Bernard John Cookson, FRCPsych, FRCP, is SUMMARY and Louis Pasteur). There he met Filomena Nitti, a consultant in general adult psych- iatry for the Royal London Hospital The author reflects on discoveries over the course daughter of a former prime minister of Italy. They of a century concerning histamine as a potent and East London NHS Foundation married in 1938 and she became her husband’slife- chemical signal and neurotransmitter, the develop- Trust. He trained in physiology and long co-worker. They moved in 1947 to the pharmacology at the University of ment of antihistamines, including promethazine, Institute of Health in Rome. In 1957 he was Oxford and he has a career-long and chlorpromazine from a common precursor, interest in psychopharmacology. His and the recognition of a major brain pathway awarded a Nobel Prize for his work in developing duties have included work in psychi- involving histamine. Although chlorpromazine has drugs ‘blocking the effects of certain substances atric intensive care units since 1988. been succeeded by numerous other antipsycho- occurring in the body, especially in its blood vessels He has co-authored two editions of tics, promethazine remains the antihistamine and skeletal muscles’ (Oliverio 1994). He and his Use of Drugs in Psychiatry, published recommended for sedation in acutely disturbed by Gaskell. research student Marianne Staub introduced the Correspondence: Dr John Cookson, patients, largely because it is potently anticholiner- first antihistamine in 1937, developed by altering Tower Hamlets Centre for Mental gic at atropinic muscarinic receptors and therefore the structures of drugs found to block known trans- Health, Mile End Hospital, Bancroft anti-Parkinsonian: this means it is also useful in mitters – acetylcholine and adrenaline – such as atro- Road, London E1 4DG, UK. -

ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of the earliest event reported): January 16, 2015 ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ireland 001-36326 Not Applicable (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission (I.R.S Employer incorporation or organization) File Number) Identification No.) Minerva House, Simmonscourt Road, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4, Ireland Not Applicable (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code 011-353-1-268-2000 Not Applicable Former name or former address, if changed since last report Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: x Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ¨ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 8.01 Other Events. This Current Report on Form 8-K is being filed pursuant to a memorandum of understanding regarding the settlement of certain litigation relating to the proposed merger (the “Merger”) between Auxilium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Auxilium”) and Avalon Merger Sub Inc. (“Merger Sub”) pursuant to that certain Amended and Restated Agreement and Plan of Merger, dated as of November 17, 2014 (the “Merger Agreement”), by and among Auxilium, Endo International plc (“Endo”), Endo U.S. -

US Pharma's Business Model

INNOVATION-FUELLED, SUSTAINABLE, INCLUSIVE GROWTH Working Paper US Pharma’s Business Model: Why It Is Broken, and How It Can Be Fixed William Lazonick Matt Hopkins Ken Jacobson Mustafa Erdem Sakinç Öner Tulum The Academic-Industry Research Network 13/2017 May This project has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation action under grant agreement No 649186 US Pharma’s Business Model: Why It Is Broken, and How It Can Be Fixed William Lazonick Matt Hopkins Ken Jacobson Mustafa Erdem Sakinç Öner Tulum The Academic-Industry Research Network (www.theAIRnet.org) Revised, May 22, 2017 Chapter for inclusion in David Tyfield, Rebecca Lave, Samuel Randalls, and Charles Thorpe, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Political Economy of Science The contents of this chapter are drawn from two contributions by the Academic- Industry Research Network to the United Nations Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines: http://www.unsgaccessmeds.org/list-of-contribution/ William Lazonick is Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Lowell; Visiting Professor, University of Ljubljana; Professeur Associé, Institut Mines- Télécom; and President, The Academic-Industry Research Network (theAIRnet); Matt Hopkins, Ken Jacobson, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç, and Öner Tulum are researchers at theAIRnet. Jacobson is also theAIRnet communications director. Sakinç has just completed a PhD in economics at the University of Bordeaux. Tulum is a PhD student at the University of Ljubljana. Funding for this research came from the Institute for New Economic Thinking (Collective and Cumulative Careers project), the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. -

The Top 15 Generic Drugmakers of 2016 by Eric Sagonowsky, Eric Palmer, Angus Liu

The top 15 generic drugmakers of 2016 by Eric Sagonowsky, Eric Palmer, Angus Liu Branded drugmakers weren’t the only ones working through a tumultuous 2016. Generics companies faced pricing pressure, too. And while branded companies suffer pricing pain on costly cutting-edge therapies, generics outfits feel the pinch with already-thin margins, making pressure all the more agonizing. How is the industry responding? By consolidating and hoping to save money, for one. Take a look at FiercePharma’s 2014 ranking, and it’s clear that some companies have made leaps too big to depend on organic growth alone. Take Teva, which topped the 2016 list as it did in 2014. It wrapped up the biggest M&A move in recent history for the generics industry, swallowing Allergan’s unbranded offerings for $40.5 billion in August. The massive move will continue to reverberate in the generics industry for years to come. Top drugmakers by 2016 generics revenue in USD billions Teva Pharmaceutical Industries 9.85 Mylan 9.43 Novartis 9 Pfizer 4.57 Allergan 4.5 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries 3.61 Fresenius 2.8 Endo International 2.57 Lupin 2.49 Sanofi 2.05 Aspen Pharmacare 2 Aurobindo Pharma 1.86 Dr. Reddy's Laboratories 1.78 Cipla 1.61 Apotex 1.6 Source: Evaluate, May 2017 Get the data Sales data for Sun Pharma, Fresenius, Lupin, Aspen Pharmacare, Aurobindo, Cipla, and Apotex are Evaluate estimates. Dr. Reddy’s data provided from company filing. Behind Teva came Mylan, which also completed a big deal last year, a $7.2 billion buyout of Sweden’s Meda. -

On Henry Miller

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. In Praise of Flight There is no salvation in becoming adapted to a world which is crazy. — Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussi La fuite reste souvent, loin des côtes, la seule façon de sauver le bateau et son équipage. Elle permet aussi de découvrir des rivages inconnus qui surgiront à l’horizon des calmes retrouvés. Rivages inconnus qu’ignoreront toujours ceux qui ont la chance apparente de pouvoir suivre la route des cargos et des tankers, la route sans imprévu imposée par les compagnies de trans- port maritime. Vous connaissez sans doute un voilier nommé “Désir.” — Henri Laborit, Éloge de la fuite A man wakes. He knows exactly what is going to happen today, or at least he thinks he does (like everyone, he knows that the unexpected might occur at any time, that he might go to see his doctor and be told he has an inoperable cancer, or his girlfriend, who stood by him all through that messy divorce, will call him at the office mid- morning to say that she has met someone else, but he keeps the thought of random harm • 1 For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. at bay as well as he is able, usually by means of a combination of superstition, moral duplicity, and steady, if uninventive, self- medication). -

LG4690 Healthcare Life Scien

Healthcare and Life Sciences Group MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS hrough decades of experience in many of the transactions that have Tdefi ned the healthcare and life sciences industry, Sullivan & Cromwell offers clients comprehensive legal expertise paired with a practical understanding of commercial realities. With a multidisciplinary and integrated global practice, we provide our healthcare and life sciences clients with leading edge transactional advice, expertise on intellectual property intensive matters and deep litigation experience that is critical to the successful execution and consummation of deals and the resolution of disputes. As the following pages demonstrate, Sullivan & Cromwell’s Healthcare and Life Sciences Group has had the privilege of working on a number of transactions that have transformed the healthcare industry. We are grateful that our clients have trusted us with many of the industry’s most signifi cant matters. We look forward to working with existing and new clients and bringing to bear our industry expertise and experience in what promises to be another exciting year in dealmaking as companies continue to position themselves strategically in an ever-evolving industry. 1 Timeline of S&C’s Headline Healthcare and Google Life Sciences S&C client Google Life Life Sciences Transactions Sciences (U.S.) announces Royal Philips its formation as the fi rst of S&C client Royal Philips Baker Bros. Advisors the Alphabet companies, (Netherlands) completes S&C client Baker Bros. Advisors (U.S.) announces their funds role Bayer Verily -

Toxicol Rev 2004; 23 (1): 21-31 GHB SYMPOSIUM 1176-2551/04/0001-0021/$31.00/0

Toxicol Rev 2004; 23 (1): 21-31 GHB SYMPOSIUM 1176-2551/04/0001-0021/$31.00/0 2004 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. γ-Butyrolactone and 1,4-Butanediol Abused Analogues of γ-Hydroxybutyrate Robert B. Palmer1,2 1 Toxicology Associates, Prof LLC, Denver, Colorado, USA 2 Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, Denver, Colorado, USA Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................21 1. Clinical Effects .......................................................................................................23 2. Diagnosis and Management ..........................................................................................25 3. Withdrawal ..........................................................................................................26 4. Conclusion ..........................................................................................................29 Abstract γ-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is a GABA-active CNS depressant, commonly used as a drug of abuse. In the early 1990s, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) warned against the use of GHB and restricted its sale. This diminished availability of GHB caused a shift toward GHB analogues such as γ-butyrolactone (GBL) and 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BD) as precursors and surrogates. Both GBL and 1,4-BD are metabolically converted to GHB. Furthermore, GBL is commonly used as a starting material for chemical conversion to GHB. As such, the clinical presentation and management of GBL and 1,4-BD -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K/A (Amendment No. 1) (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33500 JAZZ PHARMACEUTICALS PUBLIC LIMITED COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ireland 98-1032470 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification incorporation or organization) No.) Fifth Floor, Waterloo Exchange Waterloo Road, Dublin 4, Ireland 011-353-1-634-7800 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange on Title of each class which registered Ordinary shares, nominal The NASDAQ Stock Market value $0.0001 per share LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Our Operating Companies Our Vision for the Future Our Global Presence

Endo International plc Corporate Fact Sheet Endo International plc is a highly focused generics and specialty branded pharmaceutical company delivering quality medicines through excellence in development, manufacturing and commercialization. Through our operating companies – Endo Pharmaceuticals, Par Pharmaceutical and Paladin Labs – Endo is dedicated to serving patients in need. Endo commenced operations in 1997 by acquiring certain pharmaceutical products, related rights and assets from The DuPont Merck Pharmaceutical Company. Since that time, the company has expanded to include the following business segments: U.S. Branded Pharmaceuticals, U.S. Generic Pharmaceuticals and International Pharmaceuticals. Endo’s strategy is to centralize and unify our business, driving productivity improvements. We will focus on organic growth by investing in hard-to-produce generic assets & technologies and transforming the branded business into a highly focused Specialty business. Additionally, we are concentrating on differentiated and intelligent product selection to shape our company for long-term success. TM Endo has global headquarters in Dublin, Ireland, and U.S. headquarters in Malvern, Pennsylvania. We employ approximately 3,400 people worldwide.* For more information about Endo International and our operating companies, please visit www.endo.com. *As of 10/31/2017 Our Operating Companies Our Vision for the Future Endo International plc Our organization will continue to Business Segments remain steadfast in our commitment U.S. Branded U.S. Generic International to deliver pharmaceutical products of Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals uncompromising quality and value with Operating Companies the highest levels of service. We will focus Endo Par Pharmaceutical Paladin Labs Pharmaceuticals Develops, manufactures and markets Providing innovative pharmaceutical on smart product selection, operational Develops and markets high-value, safe, innovative and cost-effective generic products for the Canadian market. -

From Early Pioneers to Recent Brain Network Findings

Biological Psychiatry: Review CNNI Connectomics in Schizophrenia: From Early Pioneers to Recent Brain Network Findings Guusje Collin, Elise Turk, and Martijn P. van den Heuvel ABSTRACT Schizophrenia has been conceptualized as a brain network disorder. The historical roots of connectomics in schizophrenia go back to the late 19th century, when influential scholars such as Theodor Meynert, Carl Wernicke, Emil Kraepelin, and Eugen Bleuler worked on a theoretical understanding of the multifaceted syndrome that is currently referred to as schizophrenia. Their work contributed to the understanding that symptoms such as psychosis and cognitive disorganization might stem from abnormal integration or dissociation due to disruptions in the brain’s association fibers. As methods to test this hypothesis were long lacking, the claims of these early pioneers remained unsupported by empirical evidence for almost a century. In this review, we revisit and pay tribute to the old masters and, discussing recent findings from the developing field of disease connectomics, we examine how their pioneering hypotheses hold up in light of current evidence. Keywords: Association fibers, Connectomics, Dissociation, History of psychiatry, Integration, Schizophrenia http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.01.002 The hypothesis that schizophrenia is a disorder of brain connectomics in schizophrenia, Figure 1 shows a selection of connectivity has its roots in the 19th century, in which mental visionary scholars that contributed to the development of the illness was first attributed to the brain [for review, see (1)]. disconnectivity theory of schizophrenia. However, the methodological tools to test the disconnectivity Of note, the nomenclature in psychiatry has changed theory were long lacking, leaving it unsupported by neuro- substantially over the years (7). -

NJCG) Symposium 2019 Method Lifecycle Management, Symposium, Exhibit, and More!

North Jersey Chromatography Group (NJCG) Symposium 2019 Method Lifecycle Management, Symposium, Exhibit, and More! Register Today! September 25th, 2019 (Wed.) in Hyatt Regency Hotel, 102 Carnegie Center, Princeton, NJ 08540 Time Moderator / Speaker Title 12:30-1:00pm Registration and Refreshments Dr. Ying Hu 1:00-1:05pm Welcome Remarks Chair Ascendia Dr. Amjad Ali 1:05-1:15pm NJ-ACS NJ-ACS Chair, Merck Dr. Rosario LoBrutto 1:15-1:45pm Advancing Analytical Quality by Design Sandoz (Keynote) Dr. Peter Tattersall An Analytical Risk Assessment Program that 1:45-2:15pm BMS Evolves During Clinical Development Saji Thomas Par Pharmaceutical, Impact of Method Transfers on Lifecycle 2:15-2:45pm an ENDO International Management (LCM) of Analytical Methods Company Dr. Robert Menger Vendor Show, Posters 2:45-3:30pm Past Chair, Celgene (refreshments will be served) Technology and Software Considerations to Dr. Jinjian Zheng 3:30-4:00pm Enable Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Chair-Elect, Merck Management Continued Performance Verification of Analytical Margaret Maziarz 4:00-4:30pm Procedures Using Control Charts from Empower Waters Chromatography Data Software All Speakers 4:30-5:00pm Panel Discussion Isabelle Vu Trieu Dr. Ying Hu Raffle 5:00-5:10pm Dr. Jinjian Zheng Chair-Elect, Merck Closing Remarks 5:10-6:30pm Cocktail Hour Sponsored by Waters Corporation 1 NJCG Gratefully Acknowledges the Following Sponsors for Their Support to NJCG Symposium 2019 Sponsors 2 Invited Keynote Presentation Advancing Analytical Quality by Design Rosario LoBrutto Sandoz, Inc. (A Novartis Division) Quality by Design (QbD) concepts can be applied in process development, formulation development and analytical development. -

Printmgr File

NOTICE OF 2019 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Friday, April 26, 2019 8:00 a.m. (GMT) The 2019 Annual General Meeting (the “AGM”) of Shareholders of Perrigo Company plc (“the Company” or “Perrigo”) will be held on Friday, April 26, 2019 at 8:00 a.m. (GMT) at The Westin Dublin, College Green, Westmoreland Street, Dublin 2, Ireland, The Guinea Room, to: 1. Elect, by separate resolutions, ten director nominees to serve until the 2020 Annual General Meeting of Shareholders; 2. Ratify, in a non-binding advisory vote, the appointment of Ernst & Young LLP as the Company’s independent auditor, and authorize, in a binding vote, the Board of Directors, acting through the Audit Committee, to fix the remuneration of the auditor; 3. Provide advisory approval of the Company’s executive compensation; 4. Renew and restate the Company’s Long-Term Incentive Plan; 5. Approve the creation of distributable reserves by reducing some or all of the Company’s share premium; 6. Renew the Board’s authority to issue shares under Irish law; 7. Renew the Board’s authority to opt-out of statutory pre-emption rights under Irish law; and 8. Transact any other business that may properly come before the meeting. Proposals 1 – 4 and 6 are ordinary resolutions requiring the approval of a simple majority of the votes cast at the meeting. Proposals 5 and 7 are special resolutions requiring the approval of not less than 75% of the votes cast. All proposals are more fully described in this Proxy Statement. In addition to the above proposals, the business of the AGM shall include the consideration of the Company’s Irish Statutory Financial Statements for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018, along with the related directors’ and auditor’s reports and a review of the Company’s affairs.