Speciality Players Define M&A As Big Pharma Seeks Focus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Disclosure

Faculty Disclosure In accordance with the ACCME Standards for Commercial Support, course directors, planning committees, faculty and all others in control of the educational content of the CME activity must disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest that they or their spouse/partner may have had within the past 12 months. If an individual refuses to disclose relevant financial relationships, they will be disqualified from being a part of the planning and implementation of this CME activity. Owners and/or employees of a commercial interest with business lines or products relating to the content of the CME activity will not be permitted to participate in the planning or execution of any accredited activity. Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship Last Name Commercial Interest What Was Received For What Role AbbVie, Allergan/ Tobira Therapeutics Inc, Gilead Research Grant Research Balart Sciences Inc, Pfizer, Salix Pharmaceuticals AbbVie, Merck Honorarium Advisory Board Bau None N/A N/A Benz None N/A N/A AbbVie, Arbutus Biopharma, Dieterich Gilead Sciences, Inc., Bristol- Research Grant Consultant Myers Squibb, Merck Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences Honorarium Speaking, Consultant Inc. Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Speaking, Advisory Sciences, Inc, Salix Honorarium Frenette Board Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Merck Intercept Pharmaceuticals Honorarium Advisor Conatus Pharmaceuticals Inc Honorarium Consulting Principle Investigator, Research Grant, Han Gilead Sciences, -

Manufacturers and Wholesalers Street

Nevada AB128 Code of Conduct Compliant Companies Manufacturers and Wholesalers Street City ST Zip 10 Edison Street LLC 13 Edison Street LLC Abbott Diabetes Care Division Abbott Diagnostic Division Abbott Electrophysiology (including Kalila Medical 2- 2016)) Abbott Laboratories 100 Abbott Park Road, Dept. EC10, Bldg. APGA-2 Abbott Park IL 60064 Abbott Medical Optics Abbott Molecular Division Abbott Nutrition Products Division Abbott Vascular Division (includes Tendyne 9-2015) AbbVie, Inc. 1 N. Waukegan Road North Chicago IL 60064 Acadia Phamaceuticals 3611 Valley Centre Drive, Suite 300 San Diego CA 92130 Accelero Health Partners, LLC Acclarent, Inc. 1525-B O'Brien Dr. Menlo Park CA 94025 Accuri Cyometers, Inc. Ace Surgical Supply, Inc. 1034 Pearl St. Brockton MA 02301 Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. 420 Sawmill River Road Ardsley NY 10532 AcriVet, Inc. Actavis W.C. Holding, Inc. Morris Corporate Center III, 400 Interpace Parkway Parsippany NJ 07054 Actavis , Inc. Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. 5000 Shoreline Court, Suite 200 S. San Francisco CA 94080 Activis 400 Interpace parkway Parsippany NJ 07054 A-Dec, Inc. 2601 Crestview Dr. Newberg OR 97132 Advanced Respiratory, Inc. Advanced Sterilization Products 33 Technology Drive Irvine CA 92618 Advanced Vision Research, Inc., dba Akorn Consumer Health Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 101 Main Street, Suite 1850 Cambridge MA 02142 Aesculap Implant Systems, Inc. Aesculap, Inc. 3773 Corporate Parkway Center Valley PA 18034 Aesthera Corporation Afaxys, Inc. PO Box 20158 Charleston SC 29413 AGMS, Inc. Akorn (New Jersey) Inc. Page 1 of 23 Pages 2/15/2017 Nevada AB128 Code of Conduct Compliant Companies Akorn AG (formerly Excelvision AG) Akorn Animal Health, Inc. -

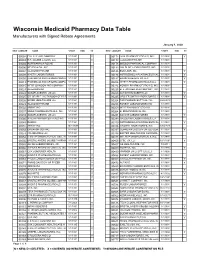

Numeric Listing of Manufacturers That Have Signed Rebate Agreements

Wisconsin Medicaid Pharmacy Data Table Manufacturers with Signed Rebate Agreements January 1, 2020 NEWLABELER NAME START END SC NEW LABELER NAME START END SC 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 1/1/1991 Y 00172 IVAX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00003 E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, LLC. 1/1/1991 Y 00173 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 00004 HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE 1/1/1991 00178 MISSION PHARMACAL COMPANY 1/1/1991 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00182 GOLDLINE LABORATORIES, INC. 1/1/1991 00007 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 00185 EON LABS, INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 Y 00186 ASTRAZENECA PHARMACEUTICAL 1/1/1991 Y 00009 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPA 1/1/1991 Y 00187 BAUSCH HEALTH US, LLC. 1/1/1991 Y 00013 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN COMPA 1/1/1991 Y 00206 WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS LLC 1/1/1991 Y 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY 1/1/1991 Y 00224 KONSYL PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 1/1/1992 00023 ALLERGAN INC 1/1/1991 00225 B. F. ASCHER AND COMPANY, INC. 1/1/1991 00024 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 1/1/1991 Y 00228 ACTAVIS ELIZABETH LLC 1/1/1991 Y 00025 GD. SEARLE LLC DIVISION OF PFIZ 1/1/1991 Y 00245 UPSHER-SMITH LABORATORIES, I 1/1/1991 Y 00026 BAYER HEALTHCARE LLC 1/1/1991 Y 00254 PAR PHARMACEUTTICAL INC. 9/28/2018 00029 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 00258 FOREST LABORATORIES INC 1/1/1991 00032 ABBVIE INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00259 MERZ PHARMACEUTICALS 1/1/1991 00037 MEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of the earliest event reported): January 16, 2015 ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ireland 001-36326 Not Applicable (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission (I.R.S Employer incorporation or organization) File Number) Identification No.) Minerva House, Simmonscourt Road, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4, Ireland Not Applicable (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code 011-353-1-268-2000 Not Applicable Former name or former address, if changed since last report Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: x Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ¨ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 8.01 Other Events. This Current Report on Form 8-K is being filed pursuant to a memorandum of understanding regarding the settlement of certain litigation relating to the proposed merger (the “Merger”) between Auxilium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Auxilium”) and Avalon Merger Sub Inc. (“Merger Sub”) pursuant to that certain Amended and Restated Agreement and Plan of Merger, dated as of November 17, 2014 (the “Merger Agreement”), by and among Auxilium, Endo International plc (“Endo”), Endo U.S. -

Manufacturers with Signed Rebate Agreements February 1 , 2011

Wisconsin Medicaid Pharmacy Data Table Manufacturers with Signed Rebate Agreements February 1 , 2011 NEWLABELER NAME START END SC NEW LABELER NAME START END SC 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 1/1/1991 Y 00126 COLGATE ORAL PHARMACEUTICAL 1/1/1991 Y 00003 E R SQUIBB AND SONS INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00131 SCHWARZ PHARMA, INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00004 HOFFMANN LAROCHE INC 1/1/1991 00132 C B FLEET COMPANY INC. 1/1/1991 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 Y 00135 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM 1/1/1995 Y 00006 MERCK SHARP & DOHME 1/1/1991 Y 00143 WEST-WARD PHARMACEUTICAL C 1/1/1991 Y 00007 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM CORPORATI 1/1/1991 Y 00145 STIEFEL LABORATORIES INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00008 WYETH AYERST LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 Y 00149 PROCTER & GAMBLE PHARMACEU 1/1/1991 Y 00009 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN 1/1/1991 Y 00168 E FOUGERA AND CO, DIV OF ALTAN 1/1/1991 Y 00013 PHARMACIA AND UPJOHN 1/1/1991 Y 00169 NOVO NORDISK PHARMACEUTICAL 1/1/1991 Y 00015 INVAMED, INC 1/1/1991 Y 00172 ZENITH LABORATORIES, INC 1/1/1991 Y 00023 ALLERGAN INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00173 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 Y 00024 SANOFI SYNTHELABO 1/1/1991 Y 00178 MISSION PHARMACAL COMPANY 1/1/1991 Y 00025 PHARMACIA CORPORATION 1/1/1991 Y 00182 GOLDLINE LABORATORIES INC 1/1/1991 Y 00026 BAYER CORP PHARMACEUTICAL DI 1/1/1991 Y 00185 EON LABS MANUFACTURING, INC. 1/1/1991 Y 00028 NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS 1/1/1991 Y 00186 ASTRAZENECA LP 1/1/1991 Y 00029 SMITHKLINE BEECHAM CORPORATI 1/1/1991 Y 00187 ICN PHARMACEUTICALS INC. -

Reporter's Handbook

2O14 RE POR TER’ S HANDBOOK for the biopharmaceutical research industry Member Companies 1 Research Associates 2 U.S. Health-Related Trade and Professional Organizations 3 Government Medical and Health Contacts 4 Voluntary Health Agencies 5 International Pharmaceutical Associations/Health Care Groups 6 Key Facts/About PhRMA 7 Company Products by Category 8 Member Companies 1 Member Companies Abbott Dept 383, AP6D 100 Abbott Park Road Abbott Park, IL 60064-3500 Phone: (847) 937-6100 Fax: (847) 937-1511 Website: www.abbott.com Melissa Brotz, Corporate Public Affairs Office: (847) 935-3456 E-Mail: [email protected] Kelly Morrison, Corporate Public Affairs, Science/Policy Office: (847) 937-3802 E-Mail: [email protected] Scott Stoffel, Corporate Public Affairs, Financial Office: (847) 936-9502 E-Mail: [email protected] Steve Chesterman, Medical Optics Office: (714) 247-8711 E-Mail: [email protected] Jonathon Hamilton, Vascular Devices 3200 Lakeside Drive, Suite 355 Santa Clara, CA 95054 Office: (408) 845-3491 E-Mail: [email protected] AbbVie 1 North Waukegan Road North Chicago, IL 60064 Phone: (847) 932-7900 Website: www.abbvie.com Gulden Mesara, Vice President, Global Commercial and Health Communications Office: (847) 938-2804 E-Mail: [email protected] Angela Sekston, Vice President, Leadership and Employee Communications Office: (847) 937-6636 E-Mail: [email protected] Morry Smulevitz, Head of U.S. Public Affairs Office: (847) 937-2152 E-Mail: [email protected] 1-1 -

US Pharma's Business Model

INNOVATION-FUELLED, SUSTAINABLE, INCLUSIVE GROWTH Working Paper US Pharma’s Business Model: Why It Is Broken, and How It Can Be Fixed William Lazonick Matt Hopkins Ken Jacobson Mustafa Erdem Sakinç Öner Tulum The Academic-Industry Research Network 13/2017 May This project has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation action under grant agreement No 649186 US Pharma’s Business Model: Why It Is Broken, and How It Can Be Fixed William Lazonick Matt Hopkins Ken Jacobson Mustafa Erdem Sakinç Öner Tulum The Academic-Industry Research Network (www.theAIRnet.org) Revised, May 22, 2017 Chapter for inclusion in David Tyfield, Rebecca Lave, Samuel Randalls, and Charles Thorpe, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Political Economy of Science The contents of this chapter are drawn from two contributions by the Academic- Industry Research Network to the United Nations Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines: http://www.unsgaccessmeds.org/list-of-contribution/ William Lazonick is Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Lowell; Visiting Professor, University of Ljubljana; Professeur Associé, Institut Mines- Télécom; and President, The Academic-Industry Research Network (theAIRnet); Matt Hopkins, Ken Jacobson, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç, and Öner Tulum are researchers at theAIRnet. Jacobson is also theAIRnet communications director. Sakinç has just completed a PhD in economics at the University of Bordeaux. Tulum is a PhD student at the University of Ljubljana. Funding for this research came from the Institute for New Economic Thinking (Collective and Cumulative Careers project), the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. -

Obesity, Diabetes, & Diet

Obesity, Diabetes, & Diet COMBINING EVIDENCE FOR ALL THREE INTO IMPROVED PATIENT CARE Case Study Louis J. Aronne, MD, FACP Weill Cornell Medical College Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons Louis J. Aronne, MD, FACP Disclosures !! Research/Grants: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Arena Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.; Metabolous Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Norvo Nordisk; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Pfizer Inc.; TransTech Pharma, Inc. !! Speakers Bureau: None !! Consultant: Allergan, Inc.; Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GI Dynamics, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, LP; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; NeuroSearch, Inc.; Novo Nordisk; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Roche Laboratories, Inc.; VIVUS, Inc.; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. !! Stockholder: Cardiometabolic Support Network, LLC !! Other Financial Interest: None !! Advisory Board: Allergan, Inc.; Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GI Dynamics, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, LP; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; NeuroSearch, Inc.; Novo Nordisk; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Roche Laboratories, Inc.; VIVUS, Inc.; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Father A.V. 04May09: 378 lbs, 5’ 11”, BMI = 53 !! Dx w/ DMII in 2004 !! Long history of obesity !! Can’t control his eating, binges !! HbA1c = 8.4% !! FPG = 166 !! TG = 241 !! UA Microalbumin = 973 !! “Can’t tolerate metformin” !! Considering RYGB, but afraid to have surgery DMII = diabetes mellitus type II; Hb = hemoglobin; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; -

Representative Healthcare and Life Sciences M&A Transactions

Representative Healthcare and Life Sciences M&A Transactions • Medtronic plc. Representing Medtronic plc in its $458 million acquisition of Twelve, Inc., a developer of devices for the treatment of chronic cardiovascular diseases. • Shire plc. Representing Shire plc in its $30 billion acquisition of Baxalta Incorporated, a developer of products for the treatment of hematology and immunology worldwide. • Pfizer Inc. Representing Pfizer Inc. in its $130 million acquisition of GlaxoSmithKline plc, a UK-based pharmaceuticals company. • Pfizer Inc. Representing Pfizer Inc. in its $17 billion acquisition of Hospira Inc., a provider of injectable drugs and infusion technologies. • Wright Medical Group. Representing Wright Medical Group in its $3.3 billion merger of equals with Tornier N.V., a Netherlands-based medical device company. • Synageva BioPharma. Represented Synageva BioPharma in its $8 billion sale to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company, develops and commercializes life-transforming therapeutic products. • Pfizer Inc. Represented Pfizer Inc. in its investment in AM-Pharma B.V., an Amsterdam-based biopharmaceutical company. • Becton, Dickinson & Company. Represented Becton, Dickinson & Company in its acquisition of CRISI Medical Systems, Inc., a medical device company, focuses on the development of drug-delivery systems. • Cubist Pharmaceuticals. Represented Cubist Pharmaceuticals in its $9 billion sale to Merck & Co. Inc., a provider of health care solutions worldwide. • Symmetry Medical. Represented Symmetry Medical Inc. In the sale of OEM Solutions business to Tecomet, a Genstar Capital portfolio company, for $450 million. As part of the deal, Symmetry, a publicly held medical device solutions provider, will also spin off and transfer to its shareholders ownership in a new company, Specialty Surgical Instruments. -

The Top 15 Generic Drugmakers of 2016 by Eric Sagonowsky, Eric Palmer, Angus Liu

The top 15 generic drugmakers of 2016 by Eric Sagonowsky, Eric Palmer, Angus Liu Branded drugmakers weren’t the only ones working through a tumultuous 2016. Generics companies faced pricing pressure, too. And while branded companies suffer pricing pain on costly cutting-edge therapies, generics outfits feel the pinch with already-thin margins, making pressure all the more agonizing. How is the industry responding? By consolidating and hoping to save money, for one. Take a look at FiercePharma’s 2014 ranking, and it’s clear that some companies have made leaps too big to depend on organic growth alone. Take Teva, which topped the 2016 list as it did in 2014. It wrapped up the biggest M&A move in recent history for the generics industry, swallowing Allergan’s unbranded offerings for $40.5 billion in August. The massive move will continue to reverberate in the generics industry for years to come. Top drugmakers by 2016 generics revenue in USD billions Teva Pharmaceutical Industries 9.85 Mylan 9.43 Novartis 9 Pfizer 4.57 Allergan 4.5 Sun Pharmaceutical Industries 3.61 Fresenius 2.8 Endo International 2.57 Lupin 2.49 Sanofi 2.05 Aspen Pharmacare 2 Aurobindo Pharma 1.86 Dr. Reddy's Laboratories 1.78 Cipla 1.61 Apotex 1.6 Source: Evaluate, May 2017 Get the data Sales data for Sun Pharma, Fresenius, Lupin, Aspen Pharmacare, Aurobindo, Cipla, and Apotex are Evaluate estimates. Dr. Reddy’s data provided from company filing. Behind Teva came Mylan, which also completed a big deal last year, a $7.2 billion buyout of Sweden’s Meda. -

Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2007 Annual Report and Form 10-K

2007 Annual Report and Form 10-K Advancing Treatment in GastroenterologyTM Corporate Mission Statement Salix is committed to being the leading U.S. specialty pharmaceutical Company licensing, developing and marketing innovative products to health care professionals to prevent or treat gastrointestinal disorders in patients while providing rewarding opportunities for our employees and creating exceptional value for our stockholders. To Our Stockholders Despite the December 28, 2007 approval of three generic delivery of mesalamine, or 5-ASA, beginning in the small balsalazide products by the Office of Generic Drugs, Salix bowel and continuing throughout the colon. Wilmington succeeded in making substantial advances in its business Pharmaceuticals, which licensed metoclopramide-ZYDIS to during 2007. From a product development standpoint we us, is moving forward in seeking FDA approval to market made impressive strides toward accessing both the multi- this fast-dissolving formulation. At this time, Wilmington is billion dollar irritable bowel syndrome market as well as targeting a fourth quarter 2008 approval. We believe that the hepatic encephalopathy market. We also progressed in our specialized sales force is positioned to effectively our effort to expand our presence in the inflammatory commercialize this patient-friendly formulation of this bowel disease market. On the marketing and sales side, widely-prescribed agent, if and when approved. we grew OSMOPREP® and MOVIPREP® to command a 25% We expect the product development success share of the prescription bowel cleansing market and we achieved during 2007 to be followed by commercial continued to grow XIFAXAN. On the business development success during 2008, as we anticipate receiving responses front we broadened our portfolio with the acquisitions of from the Food and Drug Administration during 2008 PEPCID OS® and metoclopramide-ZYDIS®. -

In Re Incretin-Based Therapies Products Liability Litigation Transfer Order

Case MDL No. 2452 Document 71 Filed 08/26/13 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES JUDICIAL PANEL on MULTIDISTRICT LITIGATION IN RE: INCRETIN MIMETICS PRODUCTS LIABILITY LITIGATION MDL No. 2452 TRANSFER ORDER Before the Panel: Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1407, plaintiffs in two Southern District of California actions move to centralize this litigation, which involves four anti-diabetic medications that plaintiffs contend cause pancreatic cancer, in the Southern District of California. This litigation currently consists of 53 actions pending in seven districts, as listed on Schedule A.1 All responding parties support centralization. Plaintiffs in fifteen Southern District of California actions and a District of Arizona action support plaintiffs’ motion in its entirety. Defendants2 support centralization in the Southern District of California or, alternatively, the District of Colorado or the Western District of Oklahoma. On the basis of the papers filed and hearing session held, we find that these actions involve common questions of fact, and that centralization of all actions in the Southern District of California will serve the convenience of the parties and witnesses and promote the just and efficient conduct of this litigation. Plaintiffs in all actions allege that the use of one or more of four anti-diabetic incretin- based medications – Janumet (sitagliptin combined with metformin), Januvia (sitagliptin), Byetta (exenatide) and Victoza (liraglutide) – caused them or their decedent to develop pancreatic cancer. Centralization will eliminate duplicative discovery; prevent inconsistent pretrial rulings (particularly on such matters as Daubert rulings); and conserve the resources of the parties, their counsel, and the judiciary. We are “typically hesitant to centralize litigation against multiple, competing defendants which marketed, manufactured and sold similar products.” In re Yellow Brass Plumbing Component Prods.