Breakfast Snacks&

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INSTRUCTION MANUAL Microwave Oven

Microwave Oven INSTRUCTION MANUAL Model:HIL2501CBSH Read these instructions carefully before using your microwave oven, and keep it carefully. If you follow the instructions, your oven will provide you with many years of good service. SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY PRECAUTIONS TO AVOID POSSIBLE EXPOSURE TO EXCESSIVE MICROWAVE ENERGY (a) Do not attempt to operate this oven with the door open since this can result in harmful exposure to microwave energy. It is important not to break or tamper with the safety interlocks. (b) Do not place any object between the oven front face and the door or allow soil or cleaner residue to accumulate on sealing surfaces. (c) WARNING: If the door or door seals are damaged, the oven must not be operated until it has been repaired by a competent person. ADDENDUM If the apparatus is not maintained in a good state of cleanliness, its surface could be degraded and affect the lifespan of the apparatus and lead to a dangerous situation. Specifications Model: HIL2501CBSH Rated Voltage: 230V~50Hz Rated Input Power(Microwave): 1450W Rated Output Power(Microwave): 900W Rated Input (Grill): 1100W Rated Input (Convection): 2500W Oven Capacity: 25L Turntable Diameter: 315mm External Dimensions(LxWxH): 512X500X305mm Net Weight: Approx. 18 kg 2 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS WARNING 1. Warning: It is hazardous for anyone other than a competent person to carry out any service or repair operation that involves the removal of a cover which gives protection against exposure to microwave energy. 2. Warning: Liquids and other foods must not be heated in sealed containers since they are liable to explode. -

Formative Qualitative Report on Complementary Feeding Practices in Pakistan.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms 7 Glossary 8 Preface 10 Foreword 11 Executive summary 12 Formative research on complementary feeding practices in Pakistan 14 1 Introduction 16 2 Purpose, objectives and scope of research 17 2.1 Purpose and objective 17 2.2 Scope of the research 18 3 Research methodology 19 3.1 Primary data collection tools 19 3.2 Respondent categories and sample size 20 3.3 Fieldwork districts 22 3.4 Field team 22 3.5 Data analysis 22 3.6 Ensuring rigour 23 3.7 Research ethics 24 3.8 Strengths and limitations of the study 24 4 Research findings and discussion 25 4.1 Socioeconomic characteristics 25 4.2 Gender roles and responsibilities at household level 26 4.3 Breastfeeding and its relation to complementary feeding 27 4.4 Initiation of solid and semi-solid foods 29 5 Complementary feeding practices 32 5.1 Minimum dietary diversity 32 5.1.1 Grains, roots and tubers 34 5.1.2 Nuts and legumes 35 5.1.3 Dairy products 36 5.1.4 Meat products 37 5.1.5 Eggs 38 5.1.6 Vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables 39 5.1.7 Other fruits and vegetables 40 5.1.8 Shelf foods 41 5.2 Minimum meal frequency 42 5.3 Minimum acceptable diet 43 5.4 Barriers and enablers to complementary feeding 44 6 Cross-cutting factors: WASH, social protection and food security 48 7 Conclusions and recommendations 50 8 Annexure 52 Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) 54 Balochistan 70 Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) 86 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) 102 Tribal districts of KP 118 Punjab 134 Sindh 152 Formative Qualitative Research on Complementary Feeding Practices in Pakistan LIST OF TABLES -

FOOD FESTIVAL 2018 Please Ensure

FOOD FESTIVAL 2018 The scent of the warm, summer air carries with it winds of memories- home-made pickles, mango jams and a hundred other recipes of love. A walk back to those good, old summer days, with food in our tummies and satiated smiles; the food fest brings us back the simple pleasures of childhood. Nostalgia hits us hard when those summer flavours tingle our nose buds and lure us into memories more precious than the mundane fast food that’s slowly infiltrating our lives. We at the Vidyalaya see the food festival as a great occasion to go exploring; across our country and the world, in search of flavours unknown and smells fresh and sweet. Open the crumbling recipe books and fish out a recipe, the scent of which takes you back on a journey that has stood the test of time. We’d like to explore local and traditional delicacies, part of our rich, culinary heritage. Traditional practises have naturally kept us in sync with the environment. Some households even today make use of every part of the edible fruit, be it the seed or the peel. In keeping with this tradition of amalgamating every natural product into a delicacy, we’d like to invite all the parents to experiment and think beyond. Please ensure: The Vidyalaya has taught us to show responsibility towards our environment and we wish to practise the same during this year’s food festival. We hope that the parents will encourage our initiative by keeping in mind a few points during the food fest. -

Traditional Beekeeping with the Indian Honey Bee (Apis Cerana

Traditional beekeeping with the Indian honey bee (Apis cerana F.) in District Chamoli, Uttarakhand, India P Tiwari, J K Tiwari, Dinesh Singh and Dhanbir Singh Department of Botany and Microbiology HNB Garhwal University, Srinagar Garhwal-246174, Uttarakhand E-mail: [email protected] Abstract microphyllus, Cornus capitata, Juglans regia, The present study aimed to recognize and Lagerstroemia spp., Myrica esculenta, document the traditional knowledge and Ougeinia oojeinensis, Phyllanthus emblica, methods of beekeeping in district Chamoli. A Prunus cerasoides, Prinsepia utilis, Pyrus structured questionnaire on different aspects spp., Rosa spp., Rubus spp., Rhododendron of traditional beekeeping was administered to arboreum, Terminalia spp., Toona hexandra, 460 traditional beekeepers to collect data from Zanthoxylum armatum and numerous 110 villages of the district during 2011. Asteracean, Crassulacean, Lamiacean Beekeeping with Apis cerana is a common members along with oil, vegetable, fruit and practice in district Chamoli and has been cereal crops which are good sources of nectar mostly carried out through traditional methods. and pollen for bees. Authentic documentation The bees are mainly kept in wall hives besides of traditional beekeeping in this region is the log and miscellaneous hives, which are lacking; the present study is an attempt to made from locally available materials. The record the knowledge and methods of people have indigenous knowledge of traditional beekeeping as practised in district beekeeping which is passed from one Chamoli. generation to another. In the hill area traditional hives are more suitable than Study area modern hives but for the drawback in colony The present study was conducted in district management. Modern beekeeping is in its Chamoli of Uttarakhand which is well known infancy in the area, so people need to be for its rich biodiversity and cultural mosaic. -

Role of Local Food As Cultural Heritage in Promoting

Indian Journal of Hospitality Management Vol: 01 Issue: 01 2019 “Role of local food as cultural heritage in promoting Bihar tourism” (Shakesh Singh, Assistant Professor , Banarsidas Chandiwala Institute of Hotel Management & Catering Technology, New Delhi) (Ranojit Kundu, Assistant Professor-HOD- Bakery, Banarsidas Chandiwala Institute of Hotel Management & Catering Technology, New Delhi) Abstract Cuisine is style of cooking food that got originated from particular region. This has always been a symbol of culture. The native people of any place are making and having various meals. These local foods as a part of the culture attract various tourists. In Bihar, tourists mainly come to visit Bodh Gaya, Patna City or to celebrate local festival – Chhath or to enjoy various circuits. Therefore, the tourism industry need to diversify their products and include more cultural tourism based components of which food is a key contender. In Bihar, the promotion of food as a component of its destination attractiveness is in its infancy at both the international and domestic level. The context of this contribution is to highlight such developments using the rationale that in order to maintain and enhance local economic and social vitality, creating back linkages between tourism and food production sectors can add value to the economy. This paper using a case study approach and researcher experience will attempt to address the strengths and opportunities of food promotion in Indian state of Bihar. Keywords- Local Food, Cuisine, Culture, Tourism 92 Indian Journal of Hospitality Management Vol: 01 Issue: 01 2019 Introduction Thousands years back, people stared travelling seven seas, in search of different ingredients and food to trade. -

Gmx 20 Ca6 Plz Convection Microwave Oven

MODEL: GMX 20 CA6 PLZ CONVECTION MICROWAVE OVEN Insta Menu 1 - Insta 1 Power Level 2 - Insta 2 3 - Insta 3 4 - Insta 4 5 - Insta 5 Grill/Combination 6 - Insta 6 7 - Insta 7 8 - Insta 8 9 - Jet Defrost Convection Clock/Weight Microwave +Convection Stop/Cancel Microwave Oven Owner's Manual Please read tthesehese instructioinstructionsns carefully bebeforefore insinstallingtalling and operating the oven. Record in ththee sspacepace belbelowow tthehe SERSERIALIAL NO. found on tthehe nameplate oonn your oven and and retain retain thisthis ininformationformation forfor futurefuture rereference.ference. SERIALSERIAL NONO.. the above image is for representative purpose, actual image of the product may vary PRECAUTIONS TO AVOID POSSIBLE EXPOSURE TO EXCESSIVE MICROWAVE ENERGY 1. Do not attempt to operate this oven with the door open since open door operation can result in harmful exposure to microwave energy. It is important not to tamper with the safety interlocks. 2. Do not place any object between the oven front face and the door or allow soil or cleaner residue to accumulate on sealing surfaces. 3. Do not operate the oven if it is damaged. It is particularly important that the oven door close properly and that there is no damage to the a. Door (bent), b. Hinges and latches (broken or loosened), c. Door seals and sealing surfaces. 4. The oven should not be adjusted or repaired by anyone except properly qualified service personnel. CONTENTS PRECAUTIONS TO AVOID POSSIBLE EXPOSURE TO EXCESSIVE MICROWAVE ENERGY ............. 1 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS -

Level and Pattern of Household Consumer Expenditure in Delhi

GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI LLeevveell aanndd PPaatttteerrnn ooff HHoouusseehhoolldd CCoonnssuummeerr EExxppeennddiittuurree iinn DDeellhhii Based on N.S.S. 64th Round July 2007 – June 2008 ( State Sample ) Groceries ……… Milk…………… Rent …………… Medicines …… School Fees … Conveyance … Vegetables … Fruits ………… Clothes……… Cooking Gas … Taxes………… DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS 148, OLD SECRETARIAT, DELHI – 110054 www.des.delhigovt.nic.in GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI LLeevveell aanndd PPaatttteerrnn ooff HHoouusseehhoolldd CCoonnssuummeerr EExxppeennddiittuurree iinn DDeellhhii Based on N.S.S. 64th Round July 2007 – June 2008 ( State Sample ) Groceries ……… Milk…………… Rent …………… Medicines …… School Fees … Conveyance … Vegetables … Fruits ………… Clothes……… Cooking Gas … Taxes………… DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS 148, OLD SECRETARIAT, DELHI – 110054 www.des.delhigovt.nic.in GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI Level and Pattern of Household Consumer Expenditure in Delhi DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS 148, OLD SECRETARIAT, DELHI – 110054 www.des.delhigovt.nic.in PREFACE The Present Report on “Level and Pattern of Household Consum er Expenditure in Delhi” is brought out by this Directorate on the basis of sam ple survey conducted under the 64th NSS (July 2007 – June 2008) round. This report contains valuable data on consum ption levels and pattern of households in Delhi. The report also provides inform ation on the m ain dem ographic features like literacy, social-group, m arital status, occupational distribution, and other aspects of living conditions like, source of energy for cooking/lighting, dwelling ownership type, and off-take from PDS. The data available from the report will be useful for policy m akers in both governm ent departm ents and other public and private institutions. -

Microwave Oven

RECIPE MANUAL MICROWAVE OVEN MC3286BPUM P/NO : MFL67281868 (00) Various Cook Functions............................................................................... 3 301 Recipes List ........................................................................................... 4 Diet Fry/Low Calorie .................................................................................... 8 Tandoor se/ Kids’ Delight ............................................................................ 40 Indian Roti Basket ........................................................................................ 59 Indian Cuisine ............................................................................................... 71 Pasterurize Milk/Tea/Dairy Delight .............................................................. 101 Cooking Aid/Steam Clean/Dosa/Ghee ........................................................ 107 Usage of Accessories/Utensils ................................................................... 116 2 Various Cook Functions Please follow the given steps to operate cook functions (Diet Fry/Low Calorie, Tandoor Se/Kids’ Delight, Indian Roti Basket, Indian Cuisine, Pasteurize Milk/Tea/Dairy Delight, Cooking Aid/Steam Clean/Dosa/Ghee) in your Microwave. Cook Diet Fry/ Tandoor Indian Indian Pasteurize Cooking Functions Low Se/Kids’ Roti Cuisine Milk/Tea Aid/Steam Calorie Delight Basket /Dairy Clean/ Delight Dosa/Ghee STEP-1 Press Press Press Press Press Press STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STOP/CLEAR STEP-2 Press -

Democristiano Elevato Dell'anno

GranaroloFelsinea Giornale Anno 64', n 142 H»r Spedizione in abb post gr. 1/70 del Partito L. 800 / arretrali L, 1.600 »'*> '*™»v- comunista Mercoledì IATO FORMMXHVXUKT FlTnìtà italiano 17 giugno 1987 * Perché il Pd cala di più DOPO IL VOTO Difficile il compromesso tra i cinque della vecchia maggioranza nelle zone operaie? I socialisti già fanno circolare un nome: il repubblicano Visentini La flessione del Pei appare più pronunciata proprio nelle sue tradizionali aree di più forte consenso, nelle zone industriali. Ma più che una protesta degli operai in senso stretto una prima analisi indica ('mainarsi del sistema so ciale di alleanze popolari intorno alla classe operaia del- l'industna. Che cosa dicono i lavoraton della Fiat e dell'Al La De rivuole palazzo Chigi fa, e dingenti sindacali come Foa, Pizzinato, Del Turco. PAGINA 7 Tredici i deputati verdi che Tredici deputati entrano alla Camera e due i il Psi cerca soluzioni di passaggio verdi senatori Cinque le donne. Tra i nomi noti quelli dei fi Due i senatori sici Mattioli e Scalia. Il suc Il vertice socialista lancia, sottovoce, la candidatu ancor maggiori che in passato titica. Le cautele del vertice ministro delle Finanze (co cesso è stato decretato per la ricostituzione dell'al sono significative. Lo stesso stantemente contestato) dall'elettorato del Nord, di ra di Visentini per la guida di un governo dì «de •^mmmm R na e del Lazio. I verdi Le cose cantatone». È «l'equilibrio» che Craxi cerca di op leanza a Cinque. Spadolini: Craxi si guarda bene dal pro \JÌ ricerca di una soluzione or •Sembra che il pentapartito nunciare perfino la parola si accompagna inoltre a una dichiarano: «Sono cambiati gli schieramenti, in Parlamen porre alla pronta rivendicazione di palazzo Chigi riflessione sui risultati che im to c'è ora una maggioranza antinucleare. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of Ready to Eat Snack Food

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(8): 4125-4130 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 08 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.708.429 A Comprehensive Analysis of Ready to Eat Snack Food Reeta Mishra*, Y.D. Mishra, B.P.S. Raghubanshi and P.P. Singh RVSKVV- Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Morena (M.P.), India Directorate of Extension Services, RVSKVV-Gwalior (M.P.), India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Ready to eat snack food (sattu) was enriched with soy and pearlmillet flour. Sattu were evaluated for nutrient and sensory characteristics. In nutrient estimation of sattu, moisture content was found maximum in treatment C, while protein, fat, ash, calorie content and K e yw or ds iron content was maximum in treatment D. The carbohydrate was found maximum in treatment C and calcium content was maximum in treatment E. Best treatment was D Soybean, Pearl millet, among C, D and E. The soy and pearlmillet flours fortified sattu had good shelf life. The Ready to eat snack food, Fortification, Sensory product is ready -to-eat so don't require much time for preparation. It is a compact source characteristics of energy and nutrients including protein, fat, iron, calcium etc. Organoleptic test of sattus Ar ticle Info showed that with regard to flavour and taste, body and texture, colour and appearance and overall acceptability, sensory characteristics of D were found to be the best. The other Accepted: treatments C and E were also found acceptable. -

Studies on Ready- To- Eat Soybean Fortified Snack Food-Sorghum Sattu

Octa Journal of Biosciences ISSN 2321 – 3663 International peer-reviewed journal May, 2013 Octa. J. Biosci. Vol. 1(1):8-16 Research Article Studies on ready- to- eat Soybean Fortified Snack Food-Sorghum Sattu Sumedha Deshpande*, PC Bargale and M.K.Tripathi Central Institute of Agricultural Engineering, Nabi Bagh, Berasia Road, Bhopal – 462 038, (M. P.)India. Received 10nd Dec. 2012 Revised 5th Feb 2013 Accepted 15th March 2013 _________________________________________________________________________________ *Email: [email protected] Abstract: ‘Sattu’ is a roasted flour mixture of cereal and pulse combination and used as ‘ready -to-eat’ snack food in most parts of India. Owing to its high nutritional balance, long shelf life and excellent taste, sattu is also a popular supplement food especially in rural India. Efforts were made in present study to fortify soybean and sorghum with Bengal gram (Chickpea) in various proportions to prepare nutritious and ready- to- eat snack. The selected grains were moisture conditioned to 30% level, roasted and powdered and then blended in different proportions so that an acceptable final product with maximum nutritional benefit and adequate shelf life was developed. Soybeans were blended in the range of 10 to 40% while sorghum was incorporated from 10 to 35% and the proportion of Bengal gram varied in the range of 40 to 70%. The products developed were analyzed for their proximate composition, shelf life and sensory evaluation. Results indicated that protein content of the developed products increased from 20 to 70% when compared to the conventional sorghum:Bengal gram sattu, while fat content increased by 21 to 121% depending upon the level of soybean fortification. -

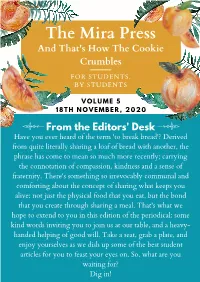

From the Editors' Desk and That's How the Cookie Crumbles

The Mira Press And That's How The Cookie Crumbles FOR STUDENTS, BY STUDENTS V O L U M E 5 1 8 T H N O V E M B E R , 2 0 2 0 From the Editors' Desk Have you ever heard of the term 'to break bread'? Derived from quite literally sharing a loaf of bread with another, the phrase has come to mean so much more recently; carrying the connotation of compassion, kindness and a sense of fraternity. There's something so irrevocably communal and comforting about the concept of sharing what keeps you alive: not just the physical food that you eat, but the bond that you create through sharing a meal. That's what we hope to extend to you in this edition of the periodical: some kind words inviting you to join us at our table, and a heavy- handed helping of good will. Take a seat, grab a plate, and enjoy yourselves as we dish up some of the best student articles for you to feast your eyes on. So, what are you waiting for? Dig in! Daily Diversity My extremely doting grandma could just not stop feeding me with all the different kind of dishes. This time she made me a special Boli Roti. Confused about what Boli Roti is? Well, it’s not a talking roti. It is a crazy food combination, where a roti (or a chapati) is fully immersed in ghee and then eaten with aamras, and it originates from Khargone. Ahhh! Talk about craziness! I have an extremely weird friend who makes me her prey for trying the food she makes.