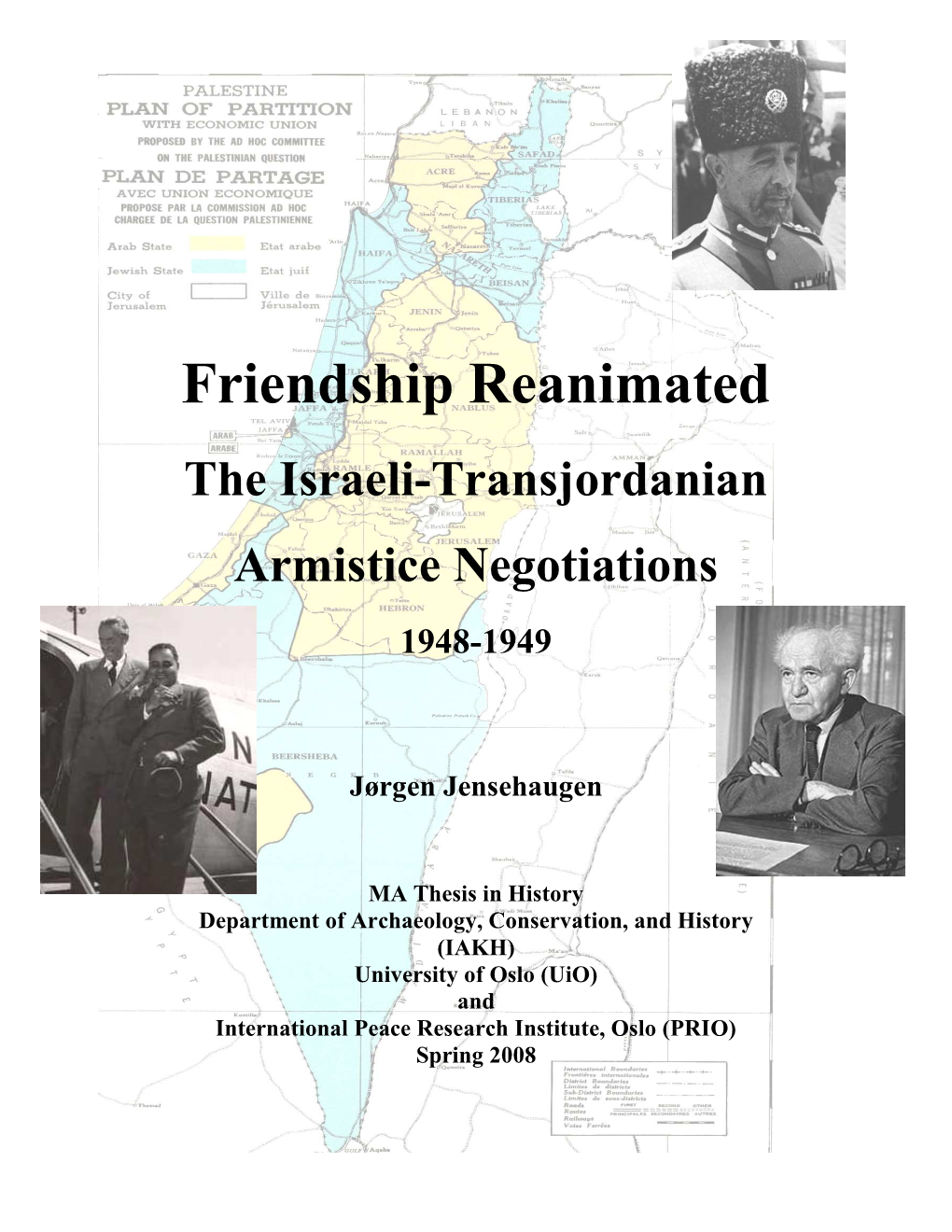

Master Thesis Jørgen Jensehaugen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of Palestinian Identity in Jordan and Saudi Arabia

i Abstract Title of Thesis: Distinctions in Diaspora: A Comparative Study of Palestinian Identity in Jordan and Saudi Arabia Erin Hahn, Bachelor of Arts, 2020 Thesis directed by: Professor Victor Lieberman The Palestinian refugee crisis is an ongoing, divisive issue in the Middle East, and the world at large. Palestinians have migrated to six out of seven continents, and formed diaspora communities in all corners of the world. Scholars affirm that the sense of Palestinian national identity is recent, only having formed as a response to the Israeli occupation of the 20th century. This thesis explores the factors that constitute that identity, and asks the question: How have the policies implemented by the Jordanian and Saudi Arabian governments influenced the formation of a national identity among Palestinians in both countries? Through conducting semi-structured interviews, it became apparent that policies of the host countries can have a powerful influence on the formation of identity among groups of displaced people. I argue that Palestinians in Jordan have widely developed a dual sense of national identity, in which they identify with both Jordan and Palestine, to varying degrees. In contrast, due to the more exclusive policies enacted by Saudi Arabia, Palestinians living there feel more isolated from their community, and do not identify as Saudi Arabian. Palestinian identity does not look the same between the two groups, the differences can be traced to policy. This thesis will explore the current state of Palestinian identity in -

When Are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-Examined

This is a repository copy of When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Version: WRRO with coversheet Article: Arielli, N (2014) When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). pp. 703-724. ISSN 0899- 3718 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Paper: Arielli, N (2014) When are foreign volunteers useful? Israel's transnational soldiers in the war of 1948 re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). 703 - 724. White Rose Research Online [email protected] When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel’s Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined Nir Arielli Abstract The literature on foreign, or “transnational,” war volunteering has fo- cused overwhelmingly on the motivations and experiences of the vol- unteers. -

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: the Most Important Events Yasser

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: The Most Important Events Yasser Arafat Foundation 1 Early 20th Century - The total population of Palestine is estimated at 600,000, including approximately 36,000 of the Jewish faith, most of whom immigrated to Palestine for purely religious reasons, the remainder Muslims and Christians, all living and praying side by side. 1901 - The Zionist Organization (later called the World Zionist Organization [WZO]) founded during the First Zionist Congress held in Basel Switzerland in 1897, establishes the “Jewish National Fund” for the purpose of purchasing land in Palestine. 1902 - Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II agrees to receives Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement and, despite Herzl’s offer to pay off the debt of the Empire, decisively rejects the idea of Zionist settlement in Palestine. - A majority of the delegates at The Fifth Zionist Congress view with favor the British offer to allocate part of the lands of Uganda for the settlement of Jews. However, the offer was rejected the following year. 2 1904 - A wave of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Poland, begins to arrive in Palestine, settling in agricultural areas. 1909 Jewish immigrants establish the city of “Tel Aviv” on the outskirts of Jaffa. 1914 - The First World War begins. - - The Jewish population in Palestine grows to 59,000, of a total population of 657,000. 1915- 1916 - In correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, wherein Hussein demands the “independence of the Arab States”, specifying the boundaries of the territories within the Ottoman rule at the time, which clearly includes Palestine. -

The Iraq Coup of Raschid Ali in 1941, the Mufti Husseini and the Farhud

The Iraq Coup of 1941, The Mufti and the Farhud Middle new peacewatc document cultur dialo histor donation top stories books Maps East s h s e g y s A detailed timeline of Iraqi history is given here, including links to UN resolutions Iraq books Map of Iraq Map of Kuwait Detailed Map of Iraq Map of Baghdad Street Map of Baghdad Iraq- Source Documents Master Document and Link Reference for the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Zionism and the Middle East The Iraq Coup Attempt of 1941, the Mufti, and the Farhud Prologue - The Iraq coup of 1941 is little studied, but very interesting. It is a dramatic illustration of the potential for the Palestine issue to destabilize the Middle East, as well a "close save" in the somewhat neglected theater of the Middle East, which was understood by Churchill to have so much potential for disaster [1]. Iraq had been governed under a British supported regency, since the death of King Feysal in September 1933. Baqr Sidqi, a popular general, staged a coup in October 1936, but was himself assassinated in 1937. In December of 1938, another coup was launched by a group of power brokers known as "The Seven." Nuri al-Sa'id was named Prime Minister. The German Consul in Baghdad, Grobba, was apparently already active before the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, soliciting support for Germany and exploiting unrest. [2]. Though the Germans were not particularly serious about aiding a revolt perhaps, they would not be unhappy if it occurred. In March of 1940 , the "The Seven" forced Nuri al-Sa'id out of office. -

Britain and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948

Britainand the Arab Israeli War Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/jps/article-pdf/16/4/50/161179/2536720.pdf by guest on 02 June 2020 of 1948 Avi Shlaim* At midnighton 14 May 1948, the Britishhigh commissioner for Palestineleft Palestine with all hisstaff, and twenty-eight years of British responsibilityfor Palestine came to an end. The storybegan with the BalfourDeclaration of November 1917 followed in April1920 by the San Remoconference's entrusting ofBritain with the Mandate for Palestine, so thatit wouldbe administeredaccording to the termsof the Balfour Declarationand preparedfor self-government. The way in whichthe mandatewas established left a terribleblot on Britain'sentire record as the greatpower responsible for governing the country. And therewas, to say theleast, something unusual about the way in which Britain retreated from themandate. As ReesWilliams, undersecretary ofstate for the colonies, toldthe House of Commons: "On the14th May, 1949, the withdrawal of theBritish Administration took place without handing over to a responsible authorityany of the assets, property or liabilitiesof the Mandatory Power. The mannerin whichthe withdrawal took place is unprecedentedin the historyof our Empire.' Whatwere the reasonsbehind the inexcusablyabrupt and reckless fashionin whichthe Britishgovernment chose to divestitself of the * Avi Shlaimis a Readerin Politicsat theUniversity of Reading, England. This paperwas preparedfor theconference on "BritishSecurity Policy 1945-1956" at King'sCollege, London, 25-26 March1987. The authorwould like to thankthe Economicand Social ResearchCouncil and the FordFoundation forresearch support. BRITAINAND THE ARAB-ISRAELIWAR OF 1948 51 Mandatefor Palestine? Very different answers are givento thisquestion by thetwo nations most directly affected by the British decision. On theJewish sidethe predominant view is thatBritain departed with full knowledge that the surroundingArab countrieswould immediatelyattack and in the expectationthat the Jewish population of Palestinewould be massacredor driveninto the sea. -

The Rise and Fall of the All-Palestine Government in Gaza

The Rise and Fall of the All Palestine Government in Gaza Avi Shlaim* The All-Palestine Government established in Gaza in September 1948 was short-lived and ill-starred, but it constituted one of the more interest- ing and instructive political experiments in the history of the Palestinian national movement. Any proposal for an independent Palestinian state inevitably raises questions about the form of the government that such a state would have. In this respect, the All-Palestine Government is not simply a historical curiosity, but a subject of considerable and enduring political relevance insofar as it highlights some of the basic dilemmas of Palestinian nationalism and above all the question of dependence on the Arab states. The Arab League and the Palestine Question In the aftermath of World War II, when the struggle for Palestine was approaching its climax, the Palestinians were in a weak and vulnerable position. Their weakness was clearly reflected in their dependence on the Arab states and on the recently-founded Arab League. Thus, when the Arab Higher Committee (AHC) was reestablished in 1946 after a nine- year hiatus, it was not by the various Palestinian political parties them- selves, as had been the case when it was founded in 1936, but by a deci- sion of the Arab League. Internally divided, with few political assets of its *Avi Shlaim is the Alastair Buchan Reader in International Relations at Oxford University and a Professorial Fellow of St. Antony's College. He is author of Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah the Zionist Movement and the Partition of Palestine (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988). -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 48

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 48 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2010 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All ri hts reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information stora e and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group ,indrush House Avenue Two Station Lane ,itney O028 40, 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 2arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 2ichael 3eetham GC3 C3E DFC AFC 7ice8President Air 2arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KC3 C3E AFC Committee Chairman Air 7ice82arshal N 3 3aldwin C3 C3E FRAeS 7ice8Chairman -roup Captain 9 D Heron O3E Secretary -roup Captain K 9 Dearman FRAeS 2embership Secretary Dr 9ack Dunham PhD CPsychol A2RAeS Treasurer 9 Boyes TD CA 2embers Air Commodore - R Pitchfork 23E 3A FRAes :9 S Cox Esq BA 2A :6r M A Fopp MA F2A FI2 t :-roup Captain A 9 Byford MA MA RAF :,ing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF ,ing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications ,ing Commander C G Jefford M3E BA 2ana er :Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS OPENIN- ADDRESS œ Air 2shl Ian Macfadyen 7 ON.Y A SIDESHO,? THE RFC AND RAF IN A 2ESOPOTA2IA 1914-1918 by Guy Warner THE RAF AR2OURED CAR CO2PANIES IN IRAB 20 C2OST.YD 1921-1947 by Dr Christopher Morris No 4 SFTS AND RASCHID A.IES WAR œ IRAB 1941 by )A , Cdr Mike Dudgeon 2ORNIN- Q&A F1 SU3STITUTION OR SU3ORDINATION? THE E2P.OY8 63 2ENT OF AIR PO,ER O7ER AF-HANISTAN AND THE NORTH8,EST FRONTIER, 1910-1939 by Clive Richards THE 9E3E. -

The Sykes-Picot Agreement at 100: Rethinking the Map of the Modern Middle East

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT AT 100: RETHINKING THE MAP OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST PANEL I: IS COLONIALISM TO BLAME? PANELISTS: SCOTT ANDERSON, AUTHOR OF “LAWRENCE IN ARABIA”; MARTIN INDYK, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION; ROBERT KAGAN, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION; DAN YERGIN, IHS MODERATOR: MICHAEL RUBIN, AEI PANEL II: THE SYKES-PICOT LEGACY, NOW AND IN THE FUTURE PANELISTS: ELLIOTT ABRAMS, COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS; RYAN CROCKER, FORMER AMBASSADOR TO IRAQ AND SYRIA; ADEED DAWISHA, MIAMI UNIVERSITY; OLIVIER DECOTTIGNIES, THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MODERATOR: DANIELLE PLETKA, AEI 2:00 PM – 4:30 PM MONDAY, MAY 16, 2016 EVENT PAGE: http://www.aei.org/events/the-sykes-picot-agreement-at-100- rethinking-the-map-of-the-modern-middle-east/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY WWW.DCTMR.COM MICHAEL RUBIN: Welcome to the American Enterprise Institute and our panel on Sykes-Picot at 100. I want to thank you all for being here. Of course, anniversaries matter, and this is one of the most significant anniversaries at least in the crafting of the modern Middle East. Now, the Sykes-Picot Agreement may not have been implemented as it was originally designed, but few would doubt that it has had tremendous impact on the eventual shaping of the Middle East. And I’m thrilled that we have a two-panel conference. Danielle Pletka, the vice president for foreign policy and defense at AEI, will moderate the second panel, but I’ll be talking a little bit about the history panel. My name is Michael Rubin. I’m a resident scholar here. I’m a historian by training, which means I get paid to predict the past. -

About the War of Independence

About the War of Independence Israel's War of Independence is the first war between the State of Israel and the neighboring Arab countries. It started on the eve of the establishment of the state (May 14, 1948) and continued until January 1949. The war broke out following the rejection of the United Nation's Partition Plan, Resolution 181 of the General Assembly (November 29, 1947), by the Arab states and the Arab Higher Committee. The representatives of the Arab states threatened to use force in order to prevent the implementation of the resolution. Stage 1: November 29, 1947 - March 31, 1948 Arab violence erupted the day after the ratification of Resolution 181. Shots were fired on a Jewish bus close to Lod airport, and a general strike declared by the Arab Higher Committee resulted in the setting fire and the plundering of the Jewish commercial district near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem. There were still 100,000 British troops stationed in Palestine, which were much stronger than both Arab and Israeli forces. Nevertheless, the British policy was not to intervene in the warfare between the two sides, except in order to safeguard the security of British forces and facilities. During this period, Arab military activities consisted of sniping and the hurling of bombs at Jewish transportation along main traffic arteries to isolated Jewish neighborhoods in ethnically mixed cites and at distant settlements. The Hagana, the military arm of the organized Yishuv, (the Jewish community of Palestine) put precedence on defensive means at first, while being careful to restrict itself to acts of retaliation against perpetrators directly responsible for the attacks. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

The State Department and Palestine, 1948

PRINCIPLE AND EXPEDIENCY: THE STATE DEPARTMENT AND PALESTINE, 1948 JUSTUS D. DOENECKE Deparlrnenl of Hitory. New College of the University of South Florida Foreign Relalions of the United Staler. 1948, Vol. V: The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, Part 11. Washington, D.C.: US. Government Printing Office, 1976. "We have no long-term Palestine policy. We do tial campaign. Israel herself, always the vastly have a short-term, open-ended policy which is outnumbered party, fought against British- set from time to time by White House direc- backed Arab armies to retain her sovereignty, tives" (p. 1222). So wrote a member of the although in so doing she gained additional ter- State Department Policy Planning Staff, Gor- ritory. Fortunately for the United States, she don P. Merriam, in July 1948. In a much- was - from the outset - not only the "sole awaited volume of the Foreign Relations series, democracy" in the Middle East but a militantly the truth of Merriam's observation is driven anti-Communist nation, a country that served home. as a bulwark against Soviet penetration of the According to the conventional wisdom, the Middle East. Palestinian refugees were en- United Nations in effect established the state of couraged by their own leadership to leave; in Israel, doing so when the General Assembly fact they ignored Jewish pleas that they remain voted for the partition of Palestine in in the land of their birth. At no time did Arabs November of 1947. President Truman ardently attempt to establish a state on the area allocated and consistently believed in a Zionist state, and them by partition. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230,