Implementation of the Prevent Duty in the Higher Education Sector in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Chapters by Branch Catchment Area

Student Chapters within Branch Catchments List of Student Chapters - Alphabetical (Date updated: 19.12.2018) Aston University Birkbeck, University of London Contact Laura Bartle Brunel University London 01793 417 483 Cardiff Metropolitan University [email protected] Coventry University Edinburgh Napier University Useful Website: Goldsmiths, University of London http://www.bcs.org/studentchapters GSM London Kingston University Lancaster University Branch Chapter(s) within Branch Catchment Leeds Beckett University Aberdeen Nil Liverpool John Moores University Girls in Tech Bedford University of Bedfordshire London Metropolitan University University of Surrey London South Bank University Berkshire University of Reading Newcastle University Birmingham Aston University Northumbria University University of Birmingham Nottingham Trent University Bristol University of Bath Open University Cheltenham & Gloucester Nil Oxford Brookes University Chester & North Wales Glyndwr University Plymouth University Coventry University Prifysgol Aberystwyth University Coventry University of Warwick Prifysgol Glyndŵr University Dorset Nil Queen Mary University London East Anglia Nil Royal Holloway University of London Edinburgh Edinburgh Napier University University of Bath Essex Nil University of Bedfordshire Glasgow University of Stirling University of Birmingham Guernsey Nil University of Bradford Hampshire Nil University of Central Lancashire Hereford & Worcester Nil University of Dundee Hertfordshire Nil University of Greenwich Humberside University of -

Progression of College Students in London to Higher Education 2011 - 2014

PROGRESSION OF COLLEGE STUDENTS IN LONDON TO HIGHER EDUCATION 2011 - 2014 Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Jill Jameson Prepared for Linking London by the HIVE-PED Research Team, Centre for Leadership and Enterprise in the Faculty of Education and Health at the University of Greenwich Authors: Sharon Smith, Hugh Joslin and Professor Jill Jameson Centre for Leadership and Enterprise, Faculty of Education and Health University of Greenwich The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Linking London, its member organisations or its sponsors. Linking London Birkbeck, University of London BMA House Tavistock Square London WC1H 9JP http://www.linkinglondon.ac.uk January 2017 Linking London Partners – Birkbeck, University of London; Brunel University, London; GSM London; Goldsmiths, University of London; King’s College London; Kingston University, London; London South Bank University; Middlesex University; Ravensbourne; Royal Central School for Speech and Drama; School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London; University College London; University of East London; University of Greenwich; University of Westminster; Barnet and Southgate College; Barking and Dagenham College; City and Islington College; City of Westminster College; The College of Enfield, Haringey and North East London; Harrow College; Haringey Sixth Form College; Havering College of Further and Higher Education; Hillcroft College; Kensington and Chelsea College; Lambeth College; Lewisham Southwark College; London South East Colleges; Morley College; Newham College of Further Education; Newham Sixth Form College; Quintin Kynaston; Sir George Monoux College; Uxbridge College; Waltham Forest College; Westminster Kingsway College; City and Guilds; London Councils Young People’s Education and Skills Board; Open College Network London; Pearson Education Ltd; TUC Unionlearn 2 Foreword It gives me great pleasure to introduce this report to you on the progression of college students in London to higher education for the years 2011 - 2014. -

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

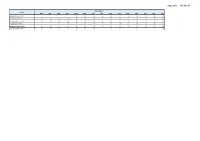

Appendix - 2019/6192

Appendix - 2019/6192 PM2.5 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 16 16 16 15 15 14 13 13 13 12 n/a Roadside Inner London 20 19 19 19 18 18 18 17 17 17 16 16 15 15 n/a Background Outer London 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 13 13 13 12 12 11 n/a Roadside Outer London 15 16 17 17 18 17 17 16 15 14 13 12 n/a Background Greater London 14 14 14 14 15 15 15 14 14 14 13 13 12 12 n/a Roadside Greater London 20 19 17 18 18 18 18 17 17 16 16 15 14 13 n/a Appendix - 2019/6194 NO2 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 44 44 43 42 42 41 40 39 39 38 37 36 35 34 n/a Roadside Inner London 68 70 71 72 73 73 73 72 71 71 70 69 65 61 n/a Background Outer London 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 32 32 31 31 30 n/a Roadside Outer London 50 50 51 51 51 51 50 49 48 47 46 45 44 44 n/a Background Greater London 40 40 39 38 38 38 37 36 36 35 35 34 33 32 n/a Roadside Greater London 59 60 61 62 62 62 62 61 60 59 58 57 55 53 n/a Appendix - 2019/6320 360 GSP College London A B C School of English Abbey Road Institute ABI College Abis Resources Academy Of Contemporary Music Accent International Access Creative College London Acorn House College Al Rawda Albemarle College Alexandra Park School Alleyn's School Alpha Building Services And Engineering Limited ALRA Altamira Training Academy Amity College Amity University [IN] London Andy Davidson College Anglia Ruskin University Anglia Ruskin University - London ANGLO EUROPEAN SCHOOL Arcadia -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Britton, Jack; Dearden, Lorraine; van der Erve, Laura; Waltmann, Ben Research Report The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings IFS Report, No. R167 Provided in Cooperation with: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London Suggested Citation: Britton, Jack; Dearden, Lorraine; van der Erve, Laura; Waltmann, Ben (2020) : The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings, IFS Report, No. R167, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, http://dx.doi.org/10.1920/re.ifs.2020.0167 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/235056 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann February 2020 A Sample Selection and Data Quality A.1 HESA Data The HESA data set presents a number of challenges. -

Sector Priorities

Sector Priorities 8.30am-10am Registration: Refreshments available 8.30am-10am 10am-11am Opening plenary 10am-11am Main Hall Welcome address: Alison Johns, Chief Executive Officer, Advance HE Keynote speech: John Gill, Editor, Times Higher Education Global higher education trends - and why they matter at home 11am-11.20am Refreshments 11am-11.20am 11.20am-12.20pm Parallel Session 1 11.20am-12.20pm White Hall 1 White Hall 2 White Hall 3 Room 553 Room 559 Room 564 Room 568 Room 220 Room 227 Room 229 Room 231 Room 371 Room 373 Room 375 SP1.1 - Interactive breakout SP1.2 - Workshop SP1.3 - Workshop SP1.4 - Workshop SP1.5 - Interactive breakout SP1.6 - Workshop SP1.7 - Workshop SP1.8 - Workshop SP1.9 - Interactive breakout SP1.10 - Interactive breakout SP1.11 - Workshop SP1.12 - Workshop SP1.13 - Interactive breakout SP1.14 - Workshop The Participation Puzzle: A project to understand how global student issues of Exploring ePortfolio use with vulnerable Spinning Seminars: A new spin on Curriculum design with global Going online: Designing an online course Unbundling higher education: Lessons Exploring interdisciplinary challenge-led Building bridges and removing barriers: A Getting to grips with SCALE-UP: An expert The same but different: Exploring staff Same difference: The shared transitional socio-economic disadvantage and ethnic Pathways to Fellowship: Roads less Heads, tales and pink elephants communities: The challenge of social Complexity as a learning tool structuring and assessing student-led communities: A shared leadership that is -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings Online Appendix February 2020

The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings Online appendix February 2020 Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann Institute for Fiscal Studies The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann February 2020 A Sample Selection and Data Quality A.1 HESA Data The HESA data set presents a number of challenges. One is lower data quality in the early years of the data: crucial information is sometimes missing or inconsistent across years. As far as charac teristics ought to be constant across years, we have dealt with missing data by taking the earliest record as authoritative.1 In cases where information on subject studied was missing, we have filled in missing data from earlier years on the same course of study.2 We also harmonised the birth year of each individual, taking data from undergraduate degrees as the most authoritative for cohorts for which no NPD data are available.3 A second challenge is changing variable definitions over time. The most important example of this for our purposes is a radical change in the way HESA classifies courses that occurred between the 2006/07 and 2007/08 academic years.4 As far as possible, we have attempted to follow HESA’s own coarser classification of degrees that includes a category for first degrees.5 However, we have diverged slightly from this classification in the interest of continuity with the pre-2007/08 classification scheme. As a result, we classify the following course codes as ‘undergraduate degrees’ for our pur poses: • the courseaim codes 18 to 24 • the qualaim codes H00, H11, H12, H16, H18, H22, H23, H24, H50, I00, I11, I16. -

Accept PTE Academic: Pearsonpte.Com/Accept United Kingdom

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept United Kingdom • Barony College • Buckinghamshire New University UK • Bath College • Burnley Training College • 360 GSP College • Bath Spa University • Calderdale College • Abacus College • Belfast Metropolitan College • Cambridge Education Group • Abbey College Birmingham • Bell’s College • Cambridge Regional College • Abbey College Cambridge • Bellerbys College - Brighton • Cambridge Ruskin International College • Abbey College London • Bellerbys College - London • Cambridge Seminars College • Abbey College Manchester • Bexhill College • Campbell Harris • Abertay University • Bilston Community College • Canterbury Christ Church • Aberystwyth University • Birkbeck, University of London University • Alchemea College • Birmingham Metropolitan College • Canterbury College • All Nations Christian college • Birmingham City University • Cardiff and Vale College (CAVC) • Alpha Business School • Birmingham College • Cardiff College International, Coleg • Alpha Tutorials • Birmingham College of Business Glan Hafren • Anderson Ross Business School • Bishop Grosseteste University • Cardiff Metropolitan University • Andy Davidson College • Blackburn College (UWIC) • Anglia Ruskin University • Blackpool and the Fylde College • Cardiff Sixth Form College • Anglo European College of • Bloomberg College • Cardiff University Chiropractic • Boston College • Cass Business School • Architectural Association School of • Bournemouth University • CATS Colleges Architecture • Bournville College • Cavendish College -

Fairtrade Student Survey

Thanks for taking part in our survey! Your university or college is taking part in project related to the things that you buy, and would like your views the subject. The survey will take around 10 minutes to complete and please be assured that all your answers are confidential. There are no right or wrong answers, we are just keen to hear your thoughts, so please be honest. Please read the following data protection information carefully: Information which identifies you (personal data) collected will only be seen by the SOS-UK project team who manage the project. Your university or college or your students' union will be able to see your views and opinions but not information that identifies you. You will not be personally identifiable in any reports or other outputs produced as a result of this research, unless we have otherwise requested. Nothing will be attributed back to you personally and your personal data will never be shared without your prior consent. You can access the data you provide or withdraw your data from the research by contacting [email protected]. The research is carried out according to the Market Research Society's code of conduct. Do you provide your consent to participate in this research and to the use of your survey responses as described above? Yes, I’m happy to continue – take me to the survey! No thanks, it’s not for me on this occasion Firstly, we would like to know a little more about you… How old are you? Please write your answer in the box below Which of the following best describes the course you're currently studying? Please select one only Entry-level (e.g. -

Business and Management Studies

Business and Management Provision in UK Higher Education Contents 2 Contents Foreword Executive summary About this report 6 Context 6 Why Business and Management? 6 Data sources and methodology 7 Quantitative data 7 Qualitative data 9 Business and Management: key characteristics 10 Distinctions between ‘Business’ and ‘Management’ 10 Accreditation 11 Institutional model and course delivery 11 Student trends 15 Undergraduate study 15 Postgraduate study 18 Diversity and protected characteristics 22 Academic staff 30 Staff numbers 30 Diversity and protected characteristics 32 Academic research 36 Research quality 36 Research priorities and impact 37 Research funding 38 Graduate skills and outcomes 43 Employer demand for skills 43 Employment and further study 44 Employment characteristics 46 Reflections and forward look 48 Glossary of terms 50 About the Academy 53 Acknowledgements 54 Foreword 3 Foreword This report is the latest in the British Academy’s reflections on teaching and research in UK higher education and forms part of our Observatory work to promote the health and diversity of SHAPE disciplines (Social Sciences, Humanities and the Arts for People and the Economy). It is a pleasure to record thanks to the experts in the field who worked with the Academy team to produce what we hope will be a highly informative and helpful insight into Business and Management today. The picture we offer in this report to a large extent relies on data from the world before the pandemic, but we have highlighted the new thinking that a year of COVID-19 has brought – concepts of purposeful business, sometimes mirroring the Academy’s own ‘Future of the Corporation’ programme, the problem of building diversity into staff profiles, especially salient after the Black Lives Matter movement, and the issue of Business and Management as financial engines of our universities. -

HEPI University Partnership Programme Anglia Ruskin

HEPI University Partnership Programme Anglia Ruskin University Arden University Arts University Bournemouth Bath Spa University BIMM (British & Irish Modern Music Institute) Birkbeck, University of London Birmingham City University Bournemouth University Bradford College Brightside Trust British Library Brunel University London Cardiff Metropolitan University Cardiff University City University London Coventry University De Montfort University Edge Hill University Edinburgh Napier University Falmouth University Glasgow Caledonian University GSM London Goldsmiths University of London Heriot-Watt University Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) ifs University College Imperial College London Keele University King’s College, London Kingston University Lancaster University Leeds Beckett University Liverpool Hope University Liverpool John Moores University London School of Economics and Political Science London South Bank University Loughborough University Manchester Metropolitan University Middlesex University New College of the Humanities Northumbria University Norwich University of the Arts Nottingham Trent University Oxford Brookes University Peter Symonds College, Winchester Plymouth College of Art Plymouth University Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) Queen Mary University of London Queen’s University Belfast Regent’s University London Royal Holloway University of London Royal Society of Chemistry Royal Veterinary College SOAS, University of London Sheffield Hallam University Staffordshire University Southampton Solent -

Download London Exhibitor List

Stand number Exhibitor Name 2 University of Aberdeen 1 Abertay University 3 Aberystwyth University 4 The Academy of Contemporary Music 5 Anglia Ruskin University 6 AECC University College 7 Arden University 8 Arts University Bournemouth 9 Aston University 10 Bangor University 11 University of Bath 12 Bath Spa University 13 University of Bedfordshire 119 Birkbeck, University of London 18 Birmingham City University 21 University of Birmingham 23 University College Birmingham 14 Bishop Grosseteste University 16 BIMM 17 Bournemouth University 15 BPP Professional Education Group 24 University of Bradford 25 University of Brighton 128 Greater Brighton Metropolitan College 51 The University of Bristol 20 UWE Bristol 26 Brunel University London 19 The University of Buckingham 27 Bucks New University 22 University of Cambridge 29 Canterbury Christ Church University 28 Capel Manor College 28 Capel Manor College 30 Cardiff University 31 Cardiff Metropolitan University 32 University Of central Lancashire 106 The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 33 University of Chester 38 University of Chichester 100 City, University of London 39 Cleveland College of Art & Design 34 University Centre Colchester 35 Cornwall College 36 Coventry University CU Coventry, CU London and CU Scarborough – Part of the Coventry 41 University Group 42 Coventry University London 44 University for the Creative Arts 37 University of Cumbria 45 De Montfort University 40 University of Derby 43 University of Dundee 46 Durham University 48 UEA - University of East Anglia 47