9515 Wingspan 24Pp For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Way October Spirit of Australia

Spirit Not just OF AUSTRALIA THE LARAPINTA TRAIL is not for the faint-hearted. an open kitchen, long dining table and comfortable couches. A 223km bushwalk through Central Australia’s West MacDonnell The hubs are positioned so they embrace the campfire – which is National Park, it offers challenges and rewards, drawing trekkers a quintessential part of any outback camping experience. along high, stony ridges radiating desert heat before ducking down The campsite closest to Alice Springs, near Simpsons Gap, is a walk in the park into cool, cycad-filled oases such as Standley Chasm. known as Nick Murcutt’s Camp. Near Serpentine Chalet, Charlie’s For some, tackling the trail became a bit more comfortable this Camp honours the late company guide, Charlie Holmes, who The pygmy possum, the northern corroboree frog, prehistoric pine year. As trekking season opened, World Expeditions showed off found the campsite, which is a short drive from ochre pits used by a remarkable new look for its two semipermanent campsites tucked the Western Arrernte people for thousands of years for medicinal, trees, “lost cities” and deep pink lakes – Australia’s 500-plus national parks within the park. The late Sydney architect Nick Murcutt and his religious and decorative purposes. yield beauty and secrets beyond compare. And a wealth of eco-adventure partner, Rachel Neeson, designed striking communal hubs for the Those returning from a hard day’s hike can now collapse on the minimal-impact campsites, that can be packed down when each couch and examine their blisters while guides cook them a dinner experiences, as this update of our parkland inventory – from the Indian Ocean hiking season is over. -

NSW Vagrant Bird Review

an atlas of the birds of new south wales and the australian capital territory Vagrant Species Ian A.W. McAllan & David J. James The species listed here are those that have been found on very few occasions (usually less than 20 times) in NSW and the ACT, and are not known to have bred here. Species that have been recorded breeding in NSW are included in the Species Accounts sections of the three volumes, even if they have been recorded in the Atlas area less than 20 times. In determining the number of records of a species, when several birds are recorded in a short period together, or whether alive or dead, these are here referred to as a ‘set’ of records. The cut-off date for vagrant records and reports is 31 December 2019. As with the rest of the Atlas, the area covered in this account includes marine waters east from the NSW coast to 160°E. This is approximately 865 km east of the coast at its widest extent in the south of the State. The New South Wales-Queensland border lies at about 28°08’S at the coast, following the centre of Border Street through Coolangatta and Tweed Heads to Point Danger (Anon. 2001a). This means that the Britannia Seamounts, where many rare seabirds have been recorded on extended pelagic trips from Southport, Queensland, are east of the NSW coast and therefore in NSW and the Atlas area. Conversely, the lookout at Point Danger is to the north of the actual Point and in Queensland but looks over both NSW and Queensland marine waters. -

Bird Vulnerability Assessments

Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change, to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia: Bird Vulnerability Assessments Attachment (2) to the Final Report June 2011 Citation: Gonzalez, D., Scott, A. & Miles, M. (2011) Bird vulnerability assessments- Attachment (2) to ‘Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia’. Report prepared for the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board. For further information please contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department of Environment and Natural Resources office. Online information available at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Permissive Licence © State of South Australia through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose subject to the conditions that you (1) attribute the Department as the copyright owner of this publication and that (2) you obtain the prior written consent of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources if you wish to modify the work or offer the publication for sale or otherwise use it or any part of it for a commercial purpose. Written requests for permission should be addressed to: Design and Production Manager Department of Environment and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

Appendices, Glossary and Index

7 Appendices Appendix A: Agency resourcing statement 2010–11 Appendix B: Portfolio Budget Statements reporting 2010–11 Appendix C: Ecologically sustainable development and environmental performance Appendix D: Freedom of information statement Appendix E: Compliance index Christmas Island red crabs. Photo: Parks Australia Appendix A: Agency Resourcing Statement 2010–11 The Agency Resourcing Statement was introduced to Portfolio Budget Statements in 2008–09 to provide information about the various funding sources that the Director of National Parks may draw upon during the year. The Director of National Parks is required to publish the Agency Resourcing Statement in the annual report that reconciles to cash reserves in the financial statements. Actual available Payments Balance appropriation Made Remaining $’000 $’000 $’000 Opening balance/Reserves at bank 38,353 – 38,353 REVENUE FROM GOVERNMENT Ordinary annual services¹ Outcome 1 – – – Total ordinary annual services – – – Other services² Non-operating 2,249 – 2,249 Total other services 2,249 – 2,249 Total annual appropriations 2,249 – 2,249 Payments from related entities3 Amounts from the portfolio department 46,444 46,444 (0) Total 46,444 46,444 (0) Total funds from Government 46,444 46,444 (0) FUNDS FROM OTHER SOURCES Interest 1,575 1,575 – Sale of goods and services 15,486 15,486 – Other 2,328 1,390 938 Total 19,389 18,451 938 Total net resourcing for DNP 106,435 64,895 41,540 All figures are GST exclusive As per the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Section 514S, DSEWPaC is directly appropriated the Director of National Parks (DNP) appropriations, which is then allocated to the DNP by the Secretary. -

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill Tasmania: 22nd January to 6th February Introduction: Where Separated from the Australian mainland by the 250km of water which forms the Bass Strait, Tasmania not only possesses a unique avifauna, but also a climate, landscape and character which are far removed from the remainder of the island continent. Once pre-trip research began, it was soon apparent that a full two weeks were required to do justice to this unique environment, and our oriGinal plans of incorporatinG a portion of south east Australia into our trip were abandoned. The following report summarises a two-week circuit of Tasmania, which was made with the aim of seeinG all island endemic and speciality bird species, but with a siGnificant focus on mammal watchinG and also enjoyinG the many outstandinG open spaces which this unique island destination has to offer. It is not written as a purely ornitholoGical report as I was accompanied by my larGely non-birdinG wife, Victoria, and as such the trip also took in numerous lonG hikes throuGh some stunninG landscapes, several siGhtseeinG forays and devoted ample time to samplinG the outstandinG food and drink for which the island is riGhtly famed. It is quite feasible to see all of Tasmania's endemic birds in just a couple of days, however it would be sacrilegious not to spend time savourinG some of the finest natural settinGs in the Antipodes, and enjoyinG what is arguably some of the most excitinG mammal watchinG on the planet. Our trip was huGely successful in achievinG the above Goals, recordinG all endemic birds, of which personal hiGhliGhts included Tasmanian Nativehen, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Boobook, four endemic honeyeaters and Forty-spotted Pardalote. -

Descriptions of Known Vocalisations of the Night Parrot Pezoporus Occidentalis

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 79–88 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36079088 Descriptions of known vocalisations of the Night Parrot Pezoporus occidentalis Nicholas P. Leseberg1, 2*, Stephen A. Murphy1, 2, 3, Nigel A. Jackett4, Bruce R. Greatwich5, Jamie Brown6, Neil Hamilton7, Leo Joseph8 and James E.M. Watson1, 2 1School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4072, Australia 2Green Fire Science, University of Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4072, Australia 3 Adaptive NRM, P.O. Box 93, Malanda QLD 4885, Australia 4Environs Kimberley, P.O. Box 2281, Broome WA 6275, Australia 5Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, P.O. Box 65, Broome WA 6725, Australia 6Paruku Rangers, Land and Sea Management Unit, P.O. Box 8252, Broome WA 6275, Australia 7Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Woodvale Research Centre, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Bentley WA 6983, Australia 8Australian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Until recently, the only descriptions of Night Parrot Pezoporus occidentalis vocalisations were anecdotal reports from observers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 2013 discovery of an extant population of Night Parrots in western Queensland led to the first contemporary descriptions, and further calls were described following the 2017 discovery of Night Parrots at a site in central Western Australia. Ongoing field studies have shown that the species has a complex repertoire and, although there are some similarities in vocalisations between sites, there is much spatial and temporal variation. It is likely that call recognition will be the primary means of detection for this cryptic species, underscoring the importance of cataloguing vocalisations across the species’ range. -

The Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran 1971) Framework for the Protection, Conservation and Wise Use of Coral Reefs Australia's Experience

The Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran 1971) Framework for the protection, conservation and wise use of coral reefs Australia's experience Report prepared by Environment Australia in conjunction with the Ramsar Bureau for: Regional Symposium ICRI Coral Reefs in the Pacific: Status and Monitoring, Resources and Management Noumea 22-24 May 2000; and ICRI Coordination and Planning Committee Noumea, 25-26 May 2000. The convention on wetlands (Ramsar, Iran 1971) Background In 1971, in the Iranian town of Ramsar, representatives from 18 countries signed one of the world's first global environmental treaties, a Convention to protect wetland ecosystems. The Convention on Wetlands, also known as the Ramsar Convention, provides a framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. There are presently 119 Contracting Parties to the Convention, with 1023 wetland sites, totalling almost 75 million hectares, designated for inclusion in the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance (As of 30 April 2000). Australia was one of the first signatories to the Convention and listed the first wetland site, the Cobourg Peninsula Aboriginal Land and Wildlife Sanctuary in the Northern Territory. Under the text of the Convention, wetlands are broadly defined as: «areas of marsh, fen, peat/and or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, ~vith water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres». In addition, the Convention provides that wetlands: «may incorporate riparian and coastal zones adjacent to the wetlands, and islands or bodies of marine water deeper than six metres at low tide lying within the wetlands». -

Kurnell B Line Upgrade Appendices

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT VOLUME 2 Appendices April 2011 Kurnell B Line Upgrade Appendix A Director-General’s Requirements A1 Director-General’s Requirements A2 Director-General’s Requirements Response Table Appendix A1 Director-General’s Requirements ----- Forwarded by William Miles/Sydney/URSCorp on 14/02/2011 02:23 p.m. ----- "Wren Suzanne" <[email protected] To <[email protected]> w.gov.au> cc 14/02/2011 02:14 p.m. Subj Caltex Refineries Part 3A Proposal - Council heads of ect consideration for environmental assessment Dear Mr Miles I refer to your letter dated 31 January 2011 regarding the Part 3A Proposal for Caltex Refineries Pty Ltd (Caltex). The proposal includes works to Banksmeadow Terminal which is located in the City of Botany Bay LGA. Council requests that the following heads of consideration be dealt with in the environmental assessment. • Visual impact of the works on the surrounding locality • Pollution that may be generated during the construction period and the operations of the terminal when works are completed • Traffic impacts that may occur on the surrounding road networks due to construction related vehicles accessing the site • Impact on any vegetation • Noise impacts that may be generated during the construction period and the operations of the terminal when works are completed • Contamination and Acid Sulfate Soils on site • Vibration impacts that may occur due to the works Council would also like to review and make a formal submission to the proposal during the exhibition period. Please note, I met you on site and I am Council’s contact officer for this matter. My contact details are below. -

Ground Parrots the Society’S Wildlife of the Year Doctor Julie Old

Ground Parrots The Society’s Wildlife of the Year Doctor Julie Old This year, the Australian Wildlife and one fox have already been detected, to yellow on the underside of their tail Society’s animal of the year consists of and subsequently, the Department and belly. Their tail also has black bars, three species, all in the Genus Pezoporus of Biodiversity, Conservation and whereas the eastern ground parrot is and otherwise known as Australia’s Attractions implemented appropriate bright green on the belly and underside ground parrots. The three species of predator control. of the tail. Both parrots are otherwise ground parrots include the western green with black flecks and have a red ground parrot (Pezoporus flaviventris), Western ground parrots were first band of colour just above the beak. the eastern ground parrot (Pezoporus photographed in 2004. Whilst they wallicus) and the night parrot (Pezoporus are yet to be formally assessed by Previously, western ground parrots occidentalis). the International Union for the were distributed along the coast of Conservation of Nature, given the low south-west Western Australia, from The Society recently supported Friends numbers of individuals, around 150, Israelite Bay to Geraldton. Now they of the Western Ground Parrot’s and the main threats to the species, are limited to two main areas on the western ground parrot recovery efforts they are likely to be listed as Critically southern coast of Western Australia, in Western Australia. In partnership Endangered. The main reason for with the largest population being in with the Department of Biodiversity, their critically endangered status is Cape Arid National Park. -

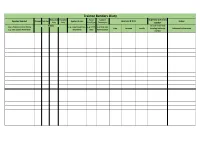

Trainee Bander's Diary (PDF

Trainee Banders Diary Extracted Handled Band Capture Supervising A-Class Species banded Banded Retraps Species Groups Location & Date Notes Only Only Size/Type Techniques Bander Totals Include name and Use CAVS & Common Name e.g. Large Passerines, e.g. 01AY, e.g. Mist-net, Date Location Locode Banding Authority Additional information e.g. 529: Superb Fairy-wren Shorebirds 09SS Hand Capture number Reference Lists 05 SS 10 AM 06 SS 11 AM Species Groups 07 SS 1 (BAT) Small Passerines 08 SS 2 (BAT) Large Passerines 09 SS 3 (BAT) Seabirds 10 SS Shorebirds 11 SS Species Parrots and Cockatoos 12 SS 6: Orange-footed Scrubfowl Gulls and Terns 13 SS 7: Malleefowl Pigeons and Doves 14 SS 8: Australian Brush-turkey Raptors 15 SS 9: Stubble Quail Waterbirds 16 SS 10: Brown Quail Fruit bats 17 SS 11: Tasmanian Quail Ordinary bats 20 SS 12: King Quail Other 21 SS 13: Red-backed Button-quail 22 SS 14: Painted Button-quail Trapping Methods 23 SS 15: Chestnut-backed Button-quail Mist-net 24 SS 16: Buff-breasted Button-quail By Hand 25 SS 17: Black-breasted Button-quail Hand-held Net 27 SS 18: Little Button-quail Cannon-net 28 SS 19: Red-chested Button-quail Cage Trap 31 SS 20: Plains-wanderer Funnel Trap 32 SS 21: Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Clap Trap 33 SS 23: Superb Fruit-Dove Bal-chatri 34 SS 24: Banded Fruit-Dove Noose Carpet 35 SS 25: Wompoo Fruit-Dove Phutt-net 36 SS 26: Pied Imperial-Pigeon Rehabiliated 37 SS 27: Topknot Pigeon Harp trap 38 SS 28: White-headed Pigeon 39 SS 29: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Band Size 03 IN 30: Peaceful Dove 01 AY 04 IN 31: Diamond -

VICTORIA MEGATOUR 2021 19Th-30Th November (12 Days)

SP & AL Starr T/A Firetail Birdwatching Tours. ABN 70397589110. 10 Boardman Close, Box Hill South, Victoria 3128, Australia. Ph: 61438520780 Email: [email protected] Website: www.firetailbirdwatchingtours.com VICTORIA MEGATOUR 2021 19th-30th November (12 days) Features of the Victoria Megatour: Start and finish in Melbourne CBD. Other pick up and drop off locations may be possible. Guided by locals and visiting key birding regions and hotspots targeting rare and iconic birds and animals across all major habitat types. Tour is set up to be medium paced with enough time in the field for good views, photographic opportunities and to connect with rarer and more cryptic birds and animals. A birding tour where photography is welcome but expect that once good views of a bird have been enjoyed we will generally move on.Tour will include some early starts and options for spotlighting activities on some nights to maximise sightings. Opting out of some activities will be possible.With the longer days of early summer a little freetime can be expected on most days . Having fun along the way is non-negotiable ! Your guide enjoys a chat and a laugh especially on the longer drives. This bird watching tour will also include a focus on all aspects of natural history, including time spent observing mammals, reptiles, plants, butterflies and anything else that catches the eye Page 1 Tour Information: Tour length: 12 days Departs: from Melbourne on the morning of Friday 19th November 2021 Concludes: in Melbourne on the evening of Tuesday 30th November 2021 Leader: Simon Starr and local guides as required. -

State of Australia's Key Biodiversity Areas 2018

State of Australia’s Key Biodiversity Areas 2018 Acknowledgements What are Key Biodiversity Areas Table of Contents BirdLife Australia thanks all the volunteers who contributed their time and expertise to collecting and why do we need them? data and helping to identify Australia’s Key Acknowldgements .................................... 2 Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). We are extremely grateful to the KBA Guardians, and all those who Key Biodiversity Areas ........................... 3 continue to monitor KBAs and contribute to the conservation and management of these areas. What are Key Biodiversity Areas Biodiversity loss is occurring at an alarming rate across the world. In the last four and why do we need them? ...............4 We would also like to thank the regional KBA Coordinators, the KBA Technical Advisory decades, there has been a 60% decline in wildlife populations across the planet. It is Committee and the BirdLife branches and networks clear that our huge impact on nature now threatens our very existence. We are reliant The KBA Program in Australia ............. 6 that have embraced and championed the KBA on a bountiful nature if we want to have a healthy and prosperous future, not just for our Program so effectively. children but for ourselves. Identifying and safeguarding sites of particular importance Measuring the health of KBAs ............. 8 BirdLife Australia’s KBA Program is made possible for biodiversity is therefore more urgent than ever. The availability of fresh water, our KBA Guardians ........................................... 9 through the generous support of BirdLife Australia’s food production systems, such as crop pollination or fisheries, and our cultural heritage donors, and we thank them for their ongoing depend directly and indirectly on a world with a rich diversity of species.