Decoding Computers: from Mainframes to Microchips Decoding Computers from Mainframes to Microchips

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vcf Pnw 2019

VCF PNW 2019 http://vcfed.org/vcf-pnw/ Schedule Saturday 10:00 AM Museum opens and VCF PNW 2019 starts 11:00 AM Erik Klein, opening comments from VCFed.org Stephen M. Jones, opening comments from Living Computers:Museum+Labs 1:00 PM Joe Decuir, IEEE Fellow, Three generations of animation machines: Atari and Amiga 2:30 PM Geoff Pool, From Minix to GNU/Linux - A Retrospective 4:00 PM Chris Rutkowski, The birth of the Business PC - How volatile markets evolve 5:00 PM Museum closes - come back tomorrow! Sunday 10:00 AM Day two of VCF PNW 2019 begins 11:00 AM John Durno, The Lost Art of Telidon 1:00 PM Lars Brinkhoff, ITS: Incompatible Timesharing System 2:30 PM Steve Jamieson, A Brief History of British Computing 4:00 PM Presentation of show awards and wrap-up Exhibitors One of the defining attributes of a Vintage Computer Festival is that exhibits are interactive; VCF exhibitors put in an amazing amount of effort to not only bring their favorite pieces of computing history, but to make them come alive. Be sure to visit all of them, ask questions, play, learn, take pictures, etc. And consider coming back one day as an exhibitor yourself! Rick Bensene, Wang Laboratories’ Electronic Calculators, An exhibit of Wang Labs electronic calculators from their first mass-market calculator, the Wang LOCI-2, through the last of their calculators, the C-Series. The exhibit includes examples of nearly every series of electronic calculator that Wang Laboratories sold, unusual and rare peripheral devices, documentation, and ephemera relating to Wang Labs calculator business. -

The Early Years of Academic Computing: L a Memoir by Douglas S

03 G A The Early Years of Academic Computing: L A Memoir by Douglas S. Gale E This is from a collection of reflections/memoirs concerning the early years of academic comput- ing, emphasizing the period when Cornell developed its own decentralized computing environ- ments and networking became a national strategic goal. ©2016 Henrietta Gale Initial Release: April 2016 (Increment 01) Second Release: April 2017 (Increments 02-04) Published by The Internet-First University Press Copy editor and proofreader: Dianne Ferriss The entire incremental book is openly available at http://hdl.handle.net/1813/36810 Books and Articles Collection – http://ecommons.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/63 The Internet-First University Press – http://ecommons.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/62 C. Memoir by Douglas S. Gale Preface and Introduction Bill Arms and Ken King have chronicled much of the early history of academic computing. Accordingly, I have tried to focus my contribution to The Early Years of Academic Computing on topics less covered by King and Arms. My contribution is organized into four chronological periods, roughly spanning the last 50 years of the 20th century, and each has an organizational theme: career transitions, the microcomputer revolution, the networking revolution, and the changing role of academic computing and networking. The theme of the first period -- career transitions -- will consider where the early practitioners of academic computing came from. Computer Science was first recognized as an academic discipline in 1962, and the early years of academic computing were led by people who had received their academic training in other disciplines. Many, if not most, came from the community of computer users and early adopters. -

DLP Discovery 4100 Development Kit Software User's Guide (Rev. A)

DLP® Discovery™ 4100 Development Platform User's Guide Literature Number: DLPU040A October 2016–Revised November 2018 Contents Revision History ........................................................................................................................... 6 Preface ........................................................................................................................................ 7 1 Overview............................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 The DLP Discovery 4100 Development Platform ...................................................................... 11 1.2 DLP Discovery 4100 Development Platform Photo.................................................................... 13 1.3 Key Components ........................................................................................................... 14 1.3.1 Xilinx Virtex 5 APPSFPGA ....................................................................................... 14 1.3.2 DLPC410 - Digital Controller for DLP Discovery 4100 Chipset ............................................. 14 1.3.3 DLPA200 - DMD Micromirror Driver ............................................................................ 14 1.3.4 DLPR410 - Configuration PROM for DLPC410 Controller................................................... 14 1.3.5 APPSFPGA Flash Configuration PROM ....................................................................... 15 1.3.6 DMD Connectors ................................................................................................ -

As We May Communicate Carson Reynolds Department of Technical Communication University of Washington

As We May Communicate Carson Reynolds Department of Technical Communication University of Washington Abstract The purpose of this article is to critique and reshape one of the fundamental paradigms of Human-Computer Interaction: the workspace. This treatise argues that the concept of a workspace—as an interaction metaphor—has certain intrinsic defects. As an alternative, a new interaction model, the communication space is offered in the hope that it will bring user interfaces closer to the ideal of human-computer symbiosis. Keywords: Workspace, Communication Space, Human-Computer Interaction Our computer systems and corresponding interfaces have come quite a long way in recent years. We no longer patiently punch cards or type obscure and unintelligible commands to interact with our computers. However, out current graphical user interfaces, for all of their advantages, still have shortcomings. It is the purpose of this paper to attempt to deduce these flaws by carefully examining our earliest and most basic formulation of what a computer should be: a workspace. The History of the Workspace The modern computerized workspace has its beginning in Vannevar Bush’s landmark article, “As We May Think.” Bush presented the MEMEX: his vision of an ideal workspace for researchers and scholars that was capable of retrieving and managing information. Bush thought that machines capable of manipulating information could transform the way that humans think. What did Bush’s idealized workspace involve? It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. -

Desktop Icon Era

Jason Hardware <p = class> </p> 20th Century Did you realize that computer weren’t born with a graphic user interface? It happened after over 30 years. 1962 Parts from four early computer. ORDVAC & BRLESC-I board On the first computers, with no operating system, every program needed the full hardware specification to run correctly and perform standard tasks, and its own drivers for peripheral devices like printers and punched paper card readers. Software <head> id = color, blue; </head> OSes Computer operating systems provide a set of functions needed and used by most application programs on a computer, and the links needed to control and synchronize computer hardware. Programming Language A programming language is a formal language, which comprises a set of instructions used to produce various kinds of output. Programming languages are used to create programs that implement specific algorithms. 80s Along with this revolutionary concept came other brilliant idea of using icons in computing. Sometimes, A picture says more than a thousand words. GUI- Graphic User Interface The history of the graphical user interface, understood as the use of graphic icons and a pointing device to control a computer, covers a five-decade span of incremental refinements, built on some constant core principles XEROX 8010 STAR 1981-1985 Invented by David Smith, Design by Norm Cox, it presented a square grid, simple looks, consistent style. APPLE-LISA 1983 Lisa was the first personal computer with a graphic user interface aimed at a wide audience of business customers. MACINTOSH 1 1984 Probably the most famous “art + Programming marriage” happened in 1982. -

Introduction to Computers

Introduction to Computers 2 BASIC MOUSE FUNCTIONS To use Windows, you will need to operate the mouse properly. POINT: Move the mouse until the pointer rests on what you want to open or use on the screen. The form of the mouse will change depending on what you are asking it to look at in Windows, so you need to be aware of what it looks like before you click. SINGLE-CLICK: The left mouse button is used to indicate choices from menus and indicate choices of options within a “dialog box” while you are working in an application program. Roll the mouse pointer on top of the choice and press the left mouse button once. RIGHT-CLICK: With a single quick press on the right mouse button, it will bring up a shortcut menu, which will contain specific options depending on where the right-click occurred. CLICK AND DRAG: This is used for a number of functions including choosing text to format, moving items around the screen, and choosing options from menu bars. Roll the mouse pointer over the item, click and hold down the left mouse button, and drag the mouse while still holding the button until you get to the desired position on the screen. Then release the mouse button. DOUBLE-CLICK: This is used to choose an application program. Roll the mouse pointer on top of the icon (picture on the desktop or within a window) of the application program you want to choose and press the left mouse button twice very rapidly. This should bring you to the window with the icons for that software package. -

PERQ Workstations by R. D. Davis

PERQ Workstations R. D. Davis Last Updated: November 6, 2003 from the Sept. 7, 1991 edition. 2 Contents 1 Preface and Dedication 11 2 History 13 2.1 PERQ History as Told by Those Who Were There . 13 2.2 PERQ History as Otherwise Researched . 16 2.3 Late 1960's . 16 2.4 1972/1973 . 17 2.5 1973 . 17 2.6 1974 . 17 2.7 1975 . 18 2.8 1976 . 18 2.9 Late 1970's . 18 2.10 1978 . 18 2.11 1979 . 19 2.12 1980 . 19 2.13 1981 . 20 2.14 1982/1983: . 22 2.15 1983-1984? . 22 2.16 1984: . 23 2.17 1985 . 24 2.18 1986: . 25 2.19 1986/1987 . 26 2.20 1997 . 27 2.21 Things whose time period is questionable . 27 3 Accent Systems Corp. 31 4 More PERQ History 33 4.1 Graphic Wonder . 33 3 4 CONTENTS 4.1.1 Historical notes from Chris Lamb . 35 4.2 Alt.sys.perq . 36 4.3 PERQ-Fanatics Mailing Lists . 36 4.4 Original uCode . 37 5 The Accent OS 39 5.1 The Accent Kernel . 42 5.2 Co-Equal Environments . 44 5.3 Accent Window Manager: Sapphire . 44 5.4 Matchmaker . 45 5.5 Microprogramming . 45 5.6 Other Info. 46 5.7 Accent and Printing/Publishing . 46 5.8 Porting POS Code to Accent . 47 5.9 Accent S5 . 47 5.10 Naming of Accent . 47 6 The Action List 49 7 Adverts and Etc. 53 7.1 PERQ-1 . 53 7.1.1 PERQ Systems and cooperative agreements: . -

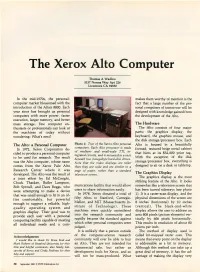

The Xerox Alto Computer, September 1981, BYTE Magazine

The Xerox Alto Computer Thomas A Wadlow 5157 Norma Way Apt 226 Livermore CA 94550 In the mid-1970s, the personal makes them worthy of mention is the computer market blossomed with the fact that a large number of the per introduction of the Altair 8800. Each sonal computers of tomorrow will be year since has brought us personal designed with knowledge gained from computers with more power, faster the development of the Alto. execution, larger memory, and better mass storage. Few computer en The Hardware thusiasts or professionals can look at The Alto consists of four major the machines of today without parts: the graphics display, the wondering: What's next? keyboard, the graphics mouse, and the disk storage/processor box. Each The Alto: a Personal Computer Photo 1: Two of the Xerox Alto personal Alto is housed in a beautifully I In 1972, Xerox Corporation de- computers. Each Alto processor is made formed, textured beige metal cabinet of medium- and small-scale TTL in cided to produce a personal computer that hints at its $32,000 price tag. tegrated circuits, and is mounted in a rack With the exception of the disk to be used for research. The result beneath two 3-megabyte hard-disk drives. was the Alto computer, whose name Note that the video displays are taller storage/ processor box, everything is comes from the Xerox Palo Alto than they are wide and are similar to a designed to sit on a desk or tabletop. Research Center where it was page of paper, rather than a standard developed. -

Decoding Computers from Mainframes to Microchips

Decoding Computers From Mainframes to Microchips It’s hard to imagine a world without computers, but there was a time, not too long ago, when they were kept under lock and key. They were stored in specially outfitted rooms, operated by specially trained personnel, performing especially important functions away from the public eye. These first computers, called mainframes, were enormous. We can trace the beginnings of today’s computers to these old mainframes, much like the fossil hunters who seek clues about early life on earth. How did we get here? How did we go from room-filling mainframes to pocket-sized computers? VISIT OUR MUSEUM! Schedule a tour for your classroom today! Go to livingcomputers. org/ and click on visit to learn more. 2245 1st Ave S | Seattle, WA 206-342-2020 | livingcomputers.org Decoding Computers: From Mainframes to Microchips What is a Computer? Basic Parts of a Computer • Hardware: The stuff you can hold — the materials and components It’s simply a machine that stores and processes information, designed to complete tasks that were too dull or difficult for humans. With the right • Software: The stuff you can use once you boot up and log-on instruction, a computer can be made to do almost anything the user can • Applications: Programs you can download and upload, open and close — conceive, from ordering a pizza pie to calculating pi. everything from the word processor you use for English class to the social media you use to chat with friends and frenemies • Operating system: The go-between for hardware and applications that manages the resource constraints of the hardware and the demands of the app Hardware is like a skateboard. -

ICON: a Case Study in Office Automation and Microcomputing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) ICON: A Case Study in Office Automation and Microcomputing Lee, R.M. IIASA Working Paper WP-80-183 December 1980 Lee, R.M. (1980) ICON: A Case Study in Office Automation and Microcomputing. IIASA Working Paper. WP-80-183 Copyright © 1980 by the author(s). http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/1286/ Working Papers on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis receive only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Institute, its National Member Organizations, or other organizations supporting the work. All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage. All copies must bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. For other purposes, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, permission must be sought by contacting [email protected] NOT FOR QUOTATION WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR ICON: A CASE STUDY IN OFFICE AUTOMATION AND MICROCOMPUTING Ronald M. Lee Working Papers are interim reports on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and have received only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily repre- sent those of the Institute or of its National Member Organizations. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED SYSTEMS ANALYSIS A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria I am especially grateful to Alan Krigman and David Ness, key characters in the case to follow, for their detailed comments and criticism of an earlier draft of this paper. -

ALTO: a Personal Computer System Hardware Manual

This document is for internal Xerox use only. ALTO: A Personal Computer System Hardware Manual August 1976 Abstract This manual is a revlSlon of the original description of the Alto: "Alto, A Personal Computer System." It includes a complete description of the Alto I and Alto II hardware and of the standard microcode (version 23). © Copyright 1975. 1976 by Xerox Corporation XEROX PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER 3333 Coyote Hill Road / Palo Alto / California 94304 This document is for internal Xerox use only. Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Microprocessor 2.1 Arithmetic section 2.2 Constant Memory 2.3 Main Memory 2.4 Microprocessor control 3.0 Emulator 3.1 Standard Instruction Set 3.2 Interrupts 3.3 Augmented Instruction Set 3.4 Bootstrapping 3.5 Hardware 4.0 Display Controller 4.1 Programming Characteristics 4.2 Hardware 4.3 Display Controller Microcode 4.4 Cursor 5.0 Miscellaneous Peri pherals 5.1 Keyboard 5.2 Mouse 5.3 Keyset 5.4 Diablo Printer 5.5 Analog Board 5.6 Parity Error Detection 6.0 Disk and Controller 7.0 Ethernet 7.1 Programming Characteristics 7.2 Ethernet Interface 7.3 Ethernet Microcode 7.4 Software Initiated Boot Feature 8.0 Control RAM 8.1 RAM-Related Tasks 8.2 Processor Bus and ALU Interface 8.3 Microinstruction Bus Interface 8.4 Reset Mode Register 8.5 Standard Emulator Access 8.6 M and S Registers 9.0 Nuts and Bolts for the Microcoder 9.1 Standard Microcode Conventions 9.2 Microcode Techniques Which Need Not Be Rediscovered Appendix A Microinstruction Summary Appendix B Reserved Memory Locations Appendix C Optional Alto Peripherals 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION This document is a description of the Alto, a small personal computing system originally designed at PARCo By 'personal computer' we mean a non-shared system containing sufficient processing power, storage, and input-output capability to satisfy the computational needs of a single user. -

Alto User's Handbook September 1979

ALTO . USER'S .HANDBOOK SEPTEMBER 1979 XEROX PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER ALTO USER'S HANDBOOK SEPTEMBER 1979 XEROX PALO ALTO RESEARCH CENTER 3333 COYOTE HILL ROAD PALO ALTO CA 94304 Copyright ,t 1979 Xerox Corporation Table of Contents Preface Alto Non-programmer's Guide 1 Bravo Manual 31 Laurel Manual 63 Markup User's Manual 85 Draw Manual 97 FTP Reference Manual U9 Neptune Reference Manual 145 ALTO NON-PROGRAMMER'S GUIDE by BUTLER W. LAMPSON ALTO USER'S HANDBOOK Preface . This handbook contains documentation for all the standard Alto services intended for use by non programmers. It is divided into seven sections, separated by heavy black dividers: The Alto Non-programmer's Guide, which has most of the general information a non programmer needs. The Bravo manual, which tells you how to prepare and edit text documents on the Alto. The Laurel manual, which tells you how to send, receive, and manipulate messages using our inter-Alto electronic mail system. The Markup and Draw manuals, which tell you how to add illustrations to documents. The Non-programmer's Guide contains some introductory material on illustrations. Finally, two reference manuals, one for FrP, which transports files between machines, and one for Neptune, which provides facilities for managing files on your Alto disk. These manuals supplement the introductory information on these two programs in the Non programmer's Guide. If you are new to the Alto, start at the beginning of the Non-programmer's Guide. Read the first four sections there, and then the first two sections of the Bravo manual.