Incestuous Marriages Where Relationship Is by Affinity and Parties Evade Law of Domicile by Attempting Marriage Elsewhere John D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

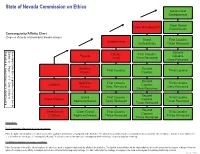

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

The Joking Relationship and Kinship: Charting a Theoretical Dependency

JASO 24/3 (1993): 251-263 THE JOKING RELATIONSHIP AND KINSHIP: CHARTING A THEORETICAL DEPENDENCY ROBERT PARKIN ALTHOUGH the anthropology of jokes and of humour generally is a relatively new phenomenon (see, for example, Apte 1985)" the anthropology of joking has a long history. It has been taken up at some point or another by most of the main theoreticians of the subject and their treatment of it often serves to characterize their general approach; moreover, there can be few anthropologists who have not enoountered it and had to deal with it in the field. What has stimulated anthropologists is the fact that societies are almost invariably internally differentiated in some way and that one does not joke with everyone. The very fact that joking has to involve at least two people ensures its social character, while the requirement not to joke is equally obviously a social injunction. The questions anthropologists have asked themselves are, why the difference, and how is it manifested in any particular society? This is a revised version of a paper first given on 26 June 1989 at the Institut fUr Ethnologie, Freie UniversiUit Berlin, in a seminar series chaired by Dr Burkhard Schnepel and entitled 'The Fool in Social Anthropological Perspective'. A German version was presented subsequently at the Deutsche Gesellschaft filr VOlkerkunde conference in Munich on 18 October 1991 and is to be published in due course in a book edited by Dr Schnepel and Dr Michael Kuper. In the present version certain aspects of the material argument have been modified, though the style of the original oral delivery has been left largely untouched. -

02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module : 16 Kinship: Definition and Approaches

Paper No. : 02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module : 16 Kinship: Definition and Approaches Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator Prof. Sabita, Department of Anthropology, Utkal University, Bhubaneshwar Gulsan Khatoon, Department of Anthropology, Utkal Content Writer University, Bhubaneswar Prof. A.K. Sinha, Department of Anthropology, Content Reviewer P anjab University, Chandigarh 1 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name 02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module Name/Title Kinship: Definition and Approaches Module Id 16 2 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches Contents Introduction 1. History of kinship study 2. Meaning and definition 3. Kinship approaches 3.1 Structure of Kinship Roles 3.2 Kinship Terminologies 3.3 Kinship Usages 3.4 Rules of Descent 3.5 Descent Group 4. Uniqueness of kinship in anthropology Anthropological symbols for kin Summary Learning outcomes After studying this module: You shall be able to understand the discovery, history and structure of kinship system You will learn the nature of kinship and the genealogical basis of society You will learn about the different approaches of kinship, kinship terminology, kinship usages, rules of descent, etc You will be able to understand the importance of kinship while conducting fieldwork. The primary objective of this module is: 3 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches To give a basic understanding to the students about Kinship, its history of origin, and subject matter It also attempts to provide an informative background about the different Kinship approaches. 4 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches INTRODUCTION The word “kinship” has been used to mean several things-indeed; the situation is so complex that it is necessary to simplify it in order to study it. -

New Patient Paperwork

AFFINITY FAMILY HEALTH REGISTRATION FORM (Please Print) Today’s date: PCP: PATIENT INFORMATION Patient’s last name: First: Middle: Mr. Miss Marital status (circle one) Mrs. Ms. Single / Mar / Div / Sep / Wid Is this your legal name? If not, what is your legal name? (Former name): Birth date: Age: Sex: Yes No / / M F Street address: Social Security no.: Home phone no.: ( ) P.O. Box: City: State: ZIP Code: Occupation: Employer: Cell or Alternate no.: ( ) Chose clinic because/Referred to clinic by (please check one Insurance Plan Hospital box): Dr. Family Friend Close to home/work Yellow Pages Other Email address: Other family members seen here: RESPONSIBLE PARTY/INSURANCE INFORMATION (Please give your insurance card to the receptionist.) Person responsible for Birth date: Address (if different): Home phone no.: bill: / / ( ) Is this person a patient Yes No here? Occupation: Employer: Employer address: Employer phone no.: ( ) Is this patient covered by Yes No insurance? Please indicate primary BCBS Aetna Cigna United Medicare insurance Medicaid Other Subscriber’s name: Subscriber’s SS no.: Birth date: Group no.: Policy no.: Co-payment: / / $ Patient’s relationship to Self Spouse Child Other subscriber: Name of secondary insurance (if Subscriber’s name: Group no.: Policy no.: applicable): Subscriber’s Subscriber’s SS no.: Subscriber’s DOB Employer: Patient’s relationship to Self Spouse Child Other subscriber: IN CASE OF EMERGENCY Name of local friend or relative (not living at same address): Relationship to patient: Home phone no.: Work phone no.: ( ) ( ) The above information is true to the best of my knowledge. I authorize my insurance benefits be paid directly to the physician. -

Beyond Fictions of Closure in Australian Aboriginal Kinship

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D RETIRED INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR SUBMITTED: DECEMBER 15, 2012 ACCEPTED: JANUARY 31, 2013 MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ISSN 1544-5879 DENHAM: BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 90 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D. Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Dedication .................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 3 1. The problem ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. Demographic history ......................................................................................................... 10 Societal boundaries, nations and drainage basins ................................................................. 10 Exogamy rates ...................................................................................................................... -

Overcoming Bioethical, Legal, and Hereditary Barriers to Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy in the USA

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2019) 36:383–393 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1370-7 COMMENTARY Overcoming bioethical, legal, and hereditary barriers to mitochondrial replacement therapy in the USA Marybeth Pompei1,2 & Francesco Pompei2 Received: 15 April 2018 /Accepted: 7 November 2018 /Published online: 15 December 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The purpose of the paper is to explore novel means to overcome the controversial ban in the USA against mitochondrial replacement therapy, a form of IVF, with the added step of replacing a woman’s diseased mutated mitochondria with a donor’s healthy mitochondria to prevent debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases. Long proven effective in non-human species, MRT recently performed in Mexico resulted in the birth of a healthy baby boy. We explore the ethics of the ban, the concerns over hereditability of mitochondrial disease and its mathematical basis, the overlooked role of Mitochondrial Eve, the financial burden of mitochondrial diseases for taxpayers, and a woman’s reproductive rights. We examine applicable court cases, particularly protection of autonomy within the reproductive rights assured by Roe v Wade. We examine the consequences of misinterpreting MRT as genetic engineering in the congressional funding prohibitions causing the MRT ban by the FDA. Allowing MRT to take place in the USA would ensure a high standard of reproductive medicine and safety for afflicted women wishing to have genetically related children, concurrently alleviating the significant financial burden of mitochondrial diseases on its taxpayers. Since MRT does not modify any genome, it falls outside the Bheritable genetic modification^ terminology of concern to Congress and the FDA. -

The Family Lifestyle in Nigeria

THE FAMILY LIFESTYLE IN NIGERIA By Morire OreOluwapo LABEODAN School of Statistics and Actuarial Science University of the Witwatersrand Private Bag 3, Wits 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa. Email Address: [email protected] [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Nigeria families are patriarchal with extended family members having more say than usual in comparison to family setups in the westernized world. Although children are very important to Nigeria families because parents believe that their children will provide support for them in their old age, family relationships are mostly guided by strict system of ‘seniority’ and male tended egoistic values. Emphasis has always been placed on male members of the family more because of their rights to both family inheritance and extension of family lineage and name. Embedded in the family system are social norms passed down from one generation to another. Most of these societal norms cut across the nation irrespective of age, educational achievement, religion, marital status and so on. With the gradual introduction of western lifestyle and religious virtues, one is interested in knowing if the Nigeria lifestyle trend is still the same. This was a trial study that examined the Nigeria family lifestyle with emphasis on the South West population of the country, who are generally referred to as ‘Yorubas’. Case studies of people interviewed were examined and reviewed based on the author’s opinion and certain defined criterias. The cases were classified using both Africa (Nigeria) and westernized virtues as being blessing, if the lifestyle benefits the individual, curse, if the lifestyle does not benefit the individual, and mixed blessing if it is a fifty percent chance in both ways. -

Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation Patrick Mcconvell

1 Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation Patrick McConvell This volume presents papers written about Aboriginal Australia for the AustKin project. By way of definition, ‘kin’ refers to kinship terminology and systems, and related matters of marriage and other behaviour; and ‘skin’ refers to what is also known as ‘social categories’ and what earlier anthropologists (e.g. Fison & Howitt 1880) called ‘social organisation’: moieties, sections, subsections and other similar categories. Kinship terms are ‘egocentric’ in anthropological parlance and skin terms are ‘sociocentric’. Different kinship terms are used depending on the ego (propositus) and who is being referred to. Conversely, skin terms are a property of the person being referred to and the category to which he or she belongs— not of their relationship to someone else. However, membership of a skin category does imply a kinship relationship. For example, I was assigned the skin (subsection) name Jampijina by the Gurindji, which means that I am classified as brother (kinship term papa) to other people of Jampijina skin, father to Jangala and Nangala, and so on. Additionally, a ‘clan’, known as a ‘local descent group’, is a group rather than a category such as a skin. Namely, it is a group of people who have common rights and interests in property, which may be intellectual property or, importantly, tracts of land. These rights and interests are generally inherited by descent, from fathers and/or mothers and more distant ancestors (although rights can be transmitted in other ways). 1 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN By contrast, people of a skin category are not collective owners of anything: for example, the people of the Jampijina subsection do not have common rights and interests in land. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 .