Out of Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

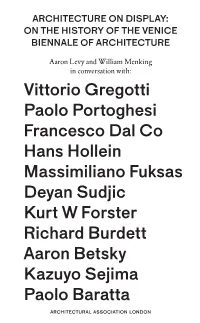

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi

1 Histories of PostWar Architecture 2 | 2018 | 1 Monument in Revolution: 1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi Kenta Matsui PhD Candidate, The University of Tokyo (Japan), Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering [email protected] MA Degree in History of Architecture at the Graduate school of the University of Tokyo. Research Fellowship for Young Scientists supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (2016-2018). His research focuses on the architectural theories of Aldo Rossi and other contemporary Italian architects in relation to the contexts of postwar Italy. ABSTRACT In the 1960’s, as Italian architectural schools faced student protests and forceful occupation attempts, Aldo Rossi tried to reform the schools through the idea of ‘tendency school’ shared with Carlo Aymonino, and to reconstruct architecture as discipline and theory. His theory has two aspects: urban analysis and architectural project. The former presents a dynamic conception of the temporal evolution of the city, as if echoing the restless social situation of the time; the latter centers on the logicality of architecture represented by monuments. This study explores the meaning of this dualism between urban analysis and architectural project as an intent for revolution, and in light of this, investigates the idea of ‘monument in revolution’. This study was supported by a research fund from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP16J05298). I would like to thank Bébio Amaro (Assistant Professor at Tianjin University, School of Architecture) for his aid in checking and revising the English text. Additionally, I would like to kindly acknowledge the many helpful suggestions and remarks provided by the anonymous reviewers, which have greatly contributed towards improving the overall quality and readability of this paper. -

The Reality of the Imaginary—Architec- and Today, by Integrating the Latest Digital Ima- Ture and the Digital Image

The Reality of the techniques. Although they developed very distinct methods of analysis, they all proceeded from the Imaginary assumption that images are more than just repre- sentations. There is the typological approach of Aldo Rossi; there is the design method of O. M. Architecture and the Digital Image Ungers, which draws on metaphors and visual ana- logies; there is James Stirling’s postmodern collage technique—to name just a few. Others we might Jörg H. Gleiter mention include mvrdv’s diagrammatic and perfor- mative design processes and the de- and recon- struction technique employed by Peter Eisenman and Bernhard Tschumi. As a matter of fact, right from the discovery of perspective in the 15th century and the invention of Cartesian space, the imaging techniques used by I am honored to welcome you all to the 10th Inter- architects have always been more than just techni- national Bauhaus Colloquium. More than 30 years ques of representation. Friedrich Nietzsche once have passed since the 1st Bauhaus Colloquium was said that all our writing tools also work on our held in 1976. The first conference was held in thoughts. How true this is also for the field of archi- honour of the historical Bauhaus in Dessau and its tecture! Drawing on different imaging techniques— 50th anniversary. Since then, the focus of the collo- whether pencil, watercolor or the click of a quium has shifted from history to theory, and mouse—design processes transcribe a certain cultu- towards contemporary architecture and its critical ral logic onto the body of architecture, be it Carte- reassessment. -

Aldo Rossi a Scientific Autobiography OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Postscript by Vincent Scully Translation by Lawrence Venuti

OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Poatscript by Vincent ScuDy Tranatotion by Lawrence Venutl Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Postscript by Vincent Scully Translation by Lawrence Venuti Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography Published for The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Chicago, Illinois. and The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York, New York, by The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 1981 Copyright @ 1981 by Other Titles in the OPPOSITIONS OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Contents A Scientific Autobiography, 1 The Institute for Architecture and BOOKS series; Drawings,Summerl980, 85 Urban Studies and Editors Postscript: Ideology in Form by Vineent Scully, 111 The Massachusetts Institute of Essays in Architectural Criticism: Peter Eisenman FigureOedits, 118 Technotogy Modern Architecture and Kenneth Frampton Biographical Note, 119 Historical Change All rights reserved. No part of this Alan Colquhoun Managing Editor book may be reproduced in any form Preface by Kenneth Frampton Lindsay Stamm Shapiro or by any means, eleetronic or mechanical, including photocopying, The Architecture ofthe City Assistant Managing Editor recording, or by any information Aldo Rossi Christopher Sweet storage and retrieval system, Introduction by Peter Eisenman without permission in writing from Translation by Diane Ghirardo and Copyeditor the publisher. Joan Ockman Joan Ockman Library ofCongress Catalogning in Designer Pnblieatian Data Massimo Vignelli Rossi, Aldo, 1931- A scientific autobiography. Coordinator "Published for the Graham Abigail Moseley Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine arta, Chieago, Illinois, and ' Production the Institute for Architecture and Larz F. Anderson II Urban Studies, New York, New York." Trustees of the Institute 1. Rossi, Aldo, 1931-. for Architecture and L'rban Studies 2. -

Oct 05 1984 Libraries the Architecture of Alvaro Siza

THE ARCHITECTURE OF ALVARO SIZA by PETER A. TESTA Bachelor of Architecture Carleton University 1978 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 1984 Peter A. Testa 1984 The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distibute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Department of Architecture August 10, 1984 Certified by__________ Stanford Anderson Professor of History and Architecture Thesis Supeltvisor Accepted by N. John Habraken Chairman Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSE TTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 05 1984 LIBRARIES THE ARCHITECTURE OF ALVARO SIZA by Peter A. Testa Submitted to the De artment of Architecture on August 10, 1984 in partial ful illment of the requirements of the Degree of Science in Architecture Studies. ABSTRACT The work of the Portuguese architect Alvaro Siza (1933) as it developed during the 1970's is an intriguing and dense expression of several contemporary concerns. The thesis focuses on three of Siza's works, the Antonio Carlos Siza house (1976-78), the projects for Kreuzberg commissioned by the International Building Exhibition of Berlin (1979), and the plan for the Malagueira district at Evora (1977- present). The analysis of these projects and Siza's few writings and statements is undertaken in an effort to tentatively articulate the principles which lie behind the forms of his architecture. From the analysis of specific works, two themes, thought to be central to Siza's enterprise, are identified and applied to a wider range of works. -

Aldo Rossi – Architect and Theorist. the Dilemmas of Architecture After Modernism 1

ALDO ROSSI – ARCHITECT AND THEORIST. THE DILEMMAS OF ARCHITECTURE AFTER MODERNISM 1 JUSTYNA WOJTAS SWOSZOWSKA From a 21st century perspective the characteristic foremost his theory of Neo-Rational architecture, work of Aldo Rossi (1931-1997) 2, the Italian architect, explained in masterly fashion in numerous essays theorist, artist, and designer, may look anachronistic. and treatises. To present an honest evaluation of Aldo Today, he is considered a representative of Rossi’s work against the background of changes postmodernism, though he referred to himself as in architecture in the second half of the twentieth a premodernist 3. In his designs he applied historical century, we must look at his work in its entirety. canons, taking them without “a pinch of salt”, as did many postmodernists who followed Robert Venturi. The Mediterranean origin of historical tendencies His inspirations were derived from the world around in architecture him, since he considered observation to be the best school of architecture. He used the basic Platonic Aldo Rossi’s career in architecture began in the solids, from which, as if from building blocks, he 1960s, when the rapid economic growth of developed created monumental architecture, concise in form countries made clear the ineffectuality of the doctrines or almost fairy-tale like (ill. 1, 2). Karen Stein 4, of mature modernism. In philosophy, politics, an American architecture critic, sees a similarity culture, art, a period of postmodernism began, a time between the creations of Aldo Rossi and the looks of of violating modernist doctrines. In architecture, the Pinocchio, Carlo Collodi’s [ ctional character: “his paradigm of the modernist movement was questioned cylindrical body, gangly columnar legs and arms, and a “revolution the against revolution” 7 began. -

Aldo Rossi Papers, 1943-1999

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c85d8tjb No online items Finding aid for the Aldo Rossi papers, 1943-1999 Finding aid prepared by Laura Schroffel Finding aid for the Aldo Rossi 880319 1 papers, 1943-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Aldo Rossi papers Date (inclusive): 1943-1999 Number: 880319 Creator/Collector: Rossi, Aldo, 1931-1997 Physical Description: 34.0 linear feet(31 boxes, 14 flat file folders, and 1 roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The Aldo Rossi papers contain a selection of works by the prolific architect, writer, artist and theorist. The collection includes notebooks, lectures and course materials, assorted writings and correspondence, drafts for publications, clippings and ephemera. A set of architectural drawings for the Palazzo dei Congressi, Milan (not realized) consisting of preliminary sketches and design plans as well as an architectural design in pencil and oil are also included. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Italian. Biographical / Historical Note One of the most important Italian architects of the second half of the 20th century Aldo Rossi is considered by some to be an integral author of the postmodern movement of architecture. Rossi received international acclaim not just as an architect but also as a designer, artist and theorist. Rossi was born in 1931 in Milan. He began his studies in architecture in 1949 at Milan Polytechnic. -

Johnson's Grid

70 Joseph Bedford 3 In Front of Lives That Leave Nothing Behind Jesús Vassallo 19 Doll’s Houses Andrew Leach 24 Letter from the Gold Coast Jean-Louis Cohen 28 Protezione Susan Holden 33 Possible Pompidous Enrique Walker 46 In Conversation with Renzo Piano & Richard Rogers Dietrich Neumann & Juergen Schulz 60 Johnson’s Grid Goswin Schwendinger 70 Paradise Regained Gavin Stamp 76 Anti-Ugly Action Sam Jacob 89 Body Building David Jenkins 92 Kaplický’s Coexistence Paul Vermeulen & Diego Inglez de Souza 98 Babel Brasileira Irina Davidovici 103 The Depth of the Street Mark Swenarton & Thomas Weaver 124 In Conversation with John Miller Will McLean 138 Atmospheric Industries Andrew Higgott 144 Eric de Maré in Search of the Functional Tradition Nicolas Grospierre 152 The Oval Offices Diane Ghirardo 159 The Blue of Aldo Rossi’s Sky Paul Mason 173 A Return to the Ideal City 176 Contributors 70 aa Files The contents of aa Files are derived from the activities Architectural Association of the Architectural Association School of Architecture. 36 Bedford Square Founded in 1847, the aa is the uk’s only independent London wc1b 3es school of architecture, offering undergraduate, t +44 (0)20 7887 4000 postgraduate and research degrees in architecture and f +44 (0)20 7414 0782 related fields. In addition, the Architectural Association aaschool.ac.uk is an international membership organisation, open to anyone with an interest in architecture. Publisher The Architectural Association For Further Information Visit aaschool.ac.uk Editorial Board or contact the -

Diocletian's Palace in Its Original State / OMA, Programmatic Lava

[above]: Diocletian's Palace in its original state / OMA, Programmatic Lava / Archizoom, No-Stop City / Le Corbusier, New Venice Hospital / SANAA, Rolex Learning Center / Diocletian's Palace today LIVING MONUMENT Mat-Organization and Diocletian's Palace Research based on ‘What if’ extreme scenarios Summer Workshop in Split, Croatia / 2016 Institute of Art History - Centre Cvito Fisković / University of Split FGAG Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture And Geodesy Diocletian’s Palace constitutes the historic core in the city center of Split. Once built as the retirement palace for the Roman emperor Diocletian, it evolved into an industrial and residential complex in the following millennia. Through continuous densification the Palace developed its current particular urban form of layered architectural and urban organizations, immersing visitors into hallucinations of past events, societies, and cultures. The intricate organization of urban patterns and fabric manifests through a palimpsest-like layering of historical traces, the palace continues to serve as a thriving nucleus within Split. In many ways the palace operates like a mat-building with its dense horizontal fabric and circulatory systems. Traditionally characterized by flatness and horizontality, Alison Smithson described mat-buildings as "close-knit patterns of neutral collectives open to growth and changes" analogous to urban formation characterized by interplay of horizontal part to whole relationships and an ever expanding system. Through tracing of urban patterns, tectonics, historical layers, influence of tourism of the Palace, distinctive systems of organization will be extrapolated from the urban fabric beyond two-dimensional nature of figure and ground. The workshop seeks to investigate Diocletian’s Palace as a living monument. -

Operative Contingencies in the Project of the Italian Tendenza

The Plan Journal 1 (1): 31-44, 2016 doi: 10.15274/tpj.2016.01.01.05 Planning Criticism: Operative Contingencies in the Project of the Italian Tendenza THEORY Pasquale De Paola ABSTRACT - In order to re-assess architecture’s critical role and redefine the disciplinary domain of its production, this essay looks beyond forms of technocratic utopias, while it historically analyzes operative theoretical contingencies relative to the “project” of the Italian Tendenza, which is examined as an historical form of ideological criticism of the discipline of architecture and its contentious relationship between intellectual and capitalistic production. Particularly, this essay explores the ideological and historiographical production of the 1960s and 1970s. This was when the term Rationalism and its theoretical body of work acquired renewed prestige replacing the ephemeral aesthetic of the Modern Movement with a grounded and critical discourse based on Aldo Rossi’s and Massimo Scolari’s position relative to the need for architecture to re-affirm its own statute, in order to free itself from any form of technocratic utopia. While questions of interdisciplinarity remain essential toward an understanding of future architectural contingencies, it is only by questioning the status quo of architecture and re-examining its past that a new sense of criticality can be generated. Keywords: Critical Call, Aldo Rossi, Massimo Scolari, Manfredo Tafuri, Tendenza “The critical act will consist of a recomposition of the fragments once they are historicized: in their remontage.” (Manfredo Tafuri) 1 31 The Plan Journal 1 (1): 31-44, 2016 - doi: 10.15274/tpj.2016.01.01.05 www.theplanjournal.com THE WILL TO THE CRITICAL Contemporary architectural production seems to be generally defined by the recent fascination with speculative technologies and interdisciplinary processes.