UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the State of Architecture A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 6 FULL BOARD MEETING MINUTES Wednesday, January 11, 2012 NYU MEDICAL CENTER 550 FIRST AVENUE Hon. Ma

MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 6 FULL BOARD MEETING MINUTES Wednesday, January 11, 2012 NYU MEDICAL CENTER 550 FIRST AVENUE Hon. Mark Thompson, Chair ATTENDANCE Members answering first roll call: Arcaro, Badi, Barrett, Buchwald, Collins, Curtis, Disman, Eggers, Figueroa, Friedman, Haile, Humphrey, Imbimbo, Keane, Landesman, Marton, McKee, Nariani, Negrete, O’Neal, Paikoff, Papush, Parrish, Pellezzi, Reiss, Schachter, Schaeffer, Scheyer, Seligman, Sepersky, Sherrod, Simon, Steinberg, Thompson, Vigh-Lebowitz, Weder, West, Winfield Members answering second roll call: Arcaro, Badi, Barrett, Buchwald, Collins, Curtis, Disman, Eggers, Figueroa, Friedman, Haile, Humphrey, Imbimbo, Keane, Landesman, Marton, McKee, Nariani, Negrete, O’Neal, Paikoff, Papush, Parrish, Pellezzi, Reiss, Schachter, Schaeffer, Scheyer, Seligman, Sepersky, Sherrod, Simon, Steinberg, Thompson, Vigh-Lebowitz, Weder, West, Winfield Excused: Dankberg, Dubnoff, Frank, Hollister, Judge, McIntosh, Absent: Garland, Gonzalez, Moses, Parise Scala, Guests signed in: B.P. Scott Stringer; Zach Gamza-Sen Krueger; Enrique Lopez-Sen. Tom Duane; Shelby Garner-Cg/M Maloney; Jenna Adams-A/M Brian Kavanagh; Jeffrey LeFrancois-A/M Gottfried; Elena Arons-C/M Dan Garodnick; C/M Jessica Lappin; Matt Walsh-C/M Dan Quart; Susan Loghito, Amir Talai, Constance Unger, Willam Zeckendorf, Jyna Scheeren, Sherrill Kazan, Kathy Thompson, Shamina deGonzaga, Paul, Adamopolous, Colin Cathcart, Paul Crawford INDEX Meeting Called to Order 3 Adoption of the Agenda 3 Roll Call 3 Public Session 3 Business Session -

Philip Skippon's Description of Florence (1664)

PHILIP SKIPPON’S DESCRIPTION OF FLORENCE (1664) in: PHILIP SKIPPON: An account of a journey made thro’ part of the Low-Countries, Germany, Italy and France, in: A collection of voyages and travels, some now printed from original manuscripts, others now first published in English (...), second edition, volume VI (London 1746) edited with an Introduction by MARGARET DALY DAVIS FONTES 51 [12 July 2009] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2010/1216/ urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-artdok-12163 1 Philip Skippon, An account of a journey made thro’ part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and France, in: A collection of voyages and travels, some now printed from original manuscripts, others now first published in English in six volumes with a general preface giving an account of the progress of navigation from its beginning, London: Printed by assignment from Messrs. Churchill for Henry Lintot; and John Osborn, at the Golden-Bell in Pater-noster Row, Vol. VI, 1746, pp. 375-749. 2 CONTENTS 3 INTRODUCTION: PHILIP SKIPPON’S DESCRIPTION OF FLORENCE (1664) 24 THE FULL TEXT OF PHILIP SKIPPON’S DESCRIPTION OF FLORENCE 45 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PHILIP SKIPPON, JOHN RAY, FRANCIS WILLUGHBY, NATHANIEL BACON 50 PAGE FACSIMILES 3 INTRODUCTION: PHILIP SKIPPON’S DESCRIPTION OF FLORENCE (1664) by Margaret Daly Davis Philip Skippon, An account of a journey made thro’ part of the Low-Countries, Germany, Italy and France, in: A collection of voyages and travels, some now printed from original manuscripts, others now first published in English (...), [London: Printed by assignment from Messrs. Churchill], 2nd ed., vol. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1St Contact Address

CURRICULUM VITAE Teresa Hubbard 1st Contact address William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor Assistant Chair Studio Division University of Texas at Austin College of Fine Arts, Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Station D1300 Austin, TX 78712-1421 USA [email protected] 2nd Contact address 4707 Shoalwood Ave Austin, TX 78756 USA [email protected] www.hubbardbirchler.net mobile +512 925 2308 Contents 2 Education and Teaching 3–5 Selected Public Lectures and Visiting Artist Appointments 5–6 Selected Academic and Public Service 6–8 Selected Solo Exhibitions 8–14 Selected Group Exhibitions 14–20 Bibliography - Selected Exhibition Catalogues and Books 20–24 Bibliography - Selected Articles 24–28 Selected Awards, Commissions and Fellowships 28 Gallery Representation 28–29 Selected Public Collections Teresa Hubbard, Curriculum Vitae - 1 / 29 Teresa Hubbard American, Irish and Swiss Citizen, born 1965 in Dublin, Ireland Education 1990–1992 M.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Canada 1988 Yale University School of Art, MFA Program, New Haven, Connecticut, USA 1987 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, USA 1985–1988 University of Texas at Austin, BFA Degree, Austin, Texas, USA 1983–1985 Louisiana State University, Liberal Arts, Baton Rouge, USA Teaching 2015–present Faculty Member, European Graduate School, (EGS), Saas-Fee, Switzerland 2014–present William and Bettye Nowlin Endowed Professor, Department of Art and Art History, College of Fine Arts, University of Texas -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

The Country House in English Women's Poetry 1650-1750: Genre, Power and Identity

The country house in English women's poetry 1650-1750: genre, power and identity Sharon L. Young A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 University of Worcester Abstract The country house in English women’s poetry 1650-1750: power, identity and genre This thesis examines the depiction of the country estate in English women’s poetry, 1650-1750. The poems discussed belong to the country house genre, work with or adapt its conventions and tropes, or belong to what may be categorised as sub-genres of the country house poem. The country house estate was the power base of the early modern world, authorizing social status, validating political power and providing an economic dominance for the ruling elite. This thesis argues that the depiction of the country estate was especially pertinent for a range of female poets. Despite the suggestive scholarship on landscape and place and the emerging field of early modern women’s literary studies and an extensive body of critical work on the country house poem, there have been to date no substantial accounts of the role of the country estate in women’s verse of this period. In response, this thesis has three main aims. Firstly, to map out the contours of women’s country house poetry – taking full account of the chronological scope, thematic and formal diversity of the texts, and the social and geographic range of the poets using the genre. Secondly, to interrogate the formal and thematic characteristics of women’s country house poetry, looking at the appropriation and adaptation of the genre. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

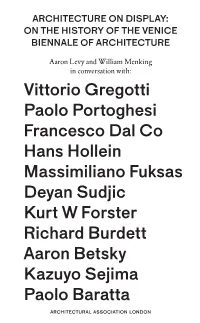

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI

Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI CURRICULUM VITAE Dott. Arch. GUIDO ZULIANI AZstudio (Owner - Principal) 235 west 108th street #52 New York City, N.Y. 10025 - USA Tel. (1) 347-570 3489 [email protected] via Gemona 78 33100 Udine - Italy Tel. (39) 329-548 9158 Tel./ Fax +39- 0432-506 254 EDUCATION AND PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS 1998 ACCADEMIA DELLE SCIENZE, LETTERE ED ARTI “GLI SVENTATI” - Udine, Italy Elected Member 1982 ORDINE DEGLI ARCHITETTI DELLA PROVINCIA DI UDINE Register architect 1980 ISTITUTO UNIVERSITARIO D'ARCHITETTURA DI VENEZIA (IUAV) today UNIVERSITÀ IUAV DI VENEZIA Dottore in Architettura (Master equivalent) - Summa cum Laude ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 1985 - Present THE COOPER UNION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE AND ART IRWIN S. CHANIN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE New York, NY 2009 - Present Professor of Architectural History 2005 - Present Professor of Architecture / Professor of Modern Architectural Concept Responsible for teaching Architectural Design II, Architectural Design IV, Thesis classes, the seminars in Modern Architectural Concepts, Analysis of Architectural Texts, Advanced Topics in Architecture 1991 - 2005 Associate Professor of Architecture 1986 - 1991 Visiting Professor of Architecture 2001 - Present Member of the Curriculum Committee Responsible for review and recommendations regarding the structure and the content of the school curriculum, currently designing the curriculum of the future post-professional Master Degree in Architecture of the Cooper Union. 2008 - Present SCHOOL OF DOCTORATE STUDIES - UNIVERSITÀ IUAV -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials.