Diversity and Abundance of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera in Greenfleet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gembrook Park Flora and Fauna Reserve

Gembrook Park Flora and Fauna Reserve Nature trail notes and information Gembrook Park is a superb example of a damp forest vegetation community with spectacular mountain grey gums, mountain ash, and messmate stringy bark trees towering overhead. The park is about 29 hectares but was originally part of a 259-hectare reserve founded by the former Zoological and Acclimatisation Society in 1873. In 1906, the land was temporarily reserved after numerous petitions from local residents and was gazetted as a permanent reserve two years later. If you would like to learn more about the park or would like to get involved and help complete various conservation projects you can join the Friends of Gembrook Park. For more information or details of how to join the ‘friends’ group, contact Cardinia Shire Council on 1300 787 624. 1. Animal haven Gembrook Park is home to many mammals, birds, insects, reptiles and amphibians. One of the most abundant is the common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), particularly in the more exposed areas, which favour the growth of grasses and other food plants. A wombat can live in as many as four to five burrows, which can be as deep as 2–3 metres. Keep a look out for wombat diggings, burrows, and scats (droppings) along both the Fern Gully and Hillside loop walking tracks. Wandering creeper (Tradescantia fluminensis). 2. Overseas trees Look around – can you find the ‘visitors’ from overseas? Friends of Gembrook Park is working to reduce weeds These two redwood trees (Sequoia sempervirens) and return this reserve to native forest. You can do originated from North America and the species is your bit by removing these plants from your garden and known to be the tallest growing in the world. -

Human Health Improvement in Sub-Saharan

ARTIGO ARTICLE 37 Human health improvement in Sub-Saharan Africa through integrated management of arthropod transmitted diseases and natural resources Johann Baumgärtner 1 Markus Bieri 2 Giuseppe Buffoni 3 Mejoramiento de la salud humana en África Gianni Gilioli 4 al sur del Sahara mediante el manejo integrado Hiremagalur Gopalan 5 de enfermedades transmitidas por artrópodos Jürgen Greiling 1 y el manejo de recursos naturales Getachew Tikubet 1 Ingeborg Van Schayk 1 1 International Centre Abstract A concept of an ecosystem approach to human health improvement in Sub-Saharan of Insect Physiology and Africa is presented here. Three factors mainly affect the physical condition of the human body: Ecology (ICIPE), P.O. Box 30772, Nairobi, Kenya. the abiotic environment, vector-transmitted diseases, and natural resources. Our concept relies 2 Swiss Federal Institute on ecological principles embedded in a social context and identifies three sets of subsystems for of Technology (ETH), 8092 study and management: human disease subsystems, natural resource subsystems, and decision- Zurich, Switzerland. 3 Italian National Agency support subsystems. To control human diseases and to secure food from resource subsystems in- for New Technology, cluding livestock or crops, integrated preventive approaches are preferred over exclusively cura- Energy, and the Environment tive and sectorial approaches. Environmental sustainability – the basis for managing matter (ENEA), C.P.31619100, La Spezia, Italy. and water flows – contributes to a healthy human environment and constitutes the basis for so- 4 Dipartimento di cial sustainability. For planning and implementation of the human health improvement Agrochimica e Agrobiologia, scheme, participatory decision-support subsystems adapted to the local conditions need to be Università degli Studi di Reggio Calabria. -

Castlemaine Naturalist April 2012 Vol

Castlemaine Naturalist April 2012 Vol. 37.3 #397 Monthly newsletter of the Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Inc. Plume moth Stangeia xerodes Maldon Photo – Noel Young Carpets in the Mt Alexander Shire. By Chris Timewell Using information from the third volume of the Moths of Victoria, moth species from the subfamily Sterrhinae (commonly known as Waves) that potentially occur in the Mount Alexander shire were addressed in a Castlemaine Naturalist article in late 2011. This present article addresses the moths from the subfamily Larentiinae potentially occurring in the Mount Alexander Shire, also based on information from the third volume of the Moths of Victoria. The Larentiinae are also known as Carpets, due to the patterns on their wings. They are small to medium sized moths. They often have transverse markings on their wings, and are usually inconspicuous when they hold their wings flat against the surface on which they are resting. There are approximately 140 species known to occur within Victoria. Using the distribution maps and other accompanying information provided on the CD that comes with volume 3 of the Moths of Victoria, the two tables below list the Carpet moths that are either known to occur or potentially occur in the Mt Alexander Shire. Victorian species that are unlikely to occur here are not listed. In summary, from the ~140 Carpet moth species from 24 different genus that are known to occur in Victoria, at least 17 species from seven genus have been confirmed as occurring in the Mt Alexander Shire (Table 1). Another 45 species from 15 of the 24 genus are predicted to potentially occur in the shire (Table 2), with the remaining ~80 species unlikely to occur here ever. -

The Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Impact of Mycosphaerella Species on Eucalypts in South-Western Australia

The Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Impact of Mycosphaerella species on Eucalypts in South-Western Australia By Aaron Maxwell BSc (Hons) Murdoch University Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology Murdoch University Perth, Western Australia April 2004 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis is of my own research, except where reference is made, and has not previously been submitted for a degree at any institution Aaron Maxwell April 2004 II Acknowledgements This work forms part of a PhD project, which is funded by an Australian Postgraduate Award (Industry) grant. Integrated Tree Cropping Pty is the industry partner involved and their financial and in kind support is gratefully received. I am indebted to my supervisors Associate Professor Bernie Dell and Dr Giles Hardy for their advice and inspiration. Also, Professor Mike Wingfield for his generosity in funding and supporting my research visit to South Africa. Dr Hardy played a great role in getting me started on this road and I cannot thank him enough for opening my eyes to the wonders of mycology and plant pathology. Professor Dell’s great wit has been a welcome addition to his wealth of knowledge. A long list of people, have helped me along the way. I thank Sarah Jackson for reviewing chapters and papers, and for extensive help with lab work and the thinking through of vexing issues. Tania Jackson for lab, field, accommodation and writing expertise. Kar-Chun Tan helped greatly with the RAPD’s research. Chris Dunne and Sarah Collins for writing advice. -

Lepidoptera: Geometridae), a Defoliator of Eucalyptus Martin J

Research Collection Journal Article Identification, synthesis and activity of sex pheromonegland components of the autumn gum moth (Lepidoptera:Geometridae), a defoliator of Eucalyptus Author(s): Steinbauer, Martin J.; Östrand, Fredrik; Bellas, Tom E.; Nilson, Anna; Andersson, Fredrik; Hedenström, Erik; Lacey, Michael J.; Schiestl, P. Florian Publication Date: 2004 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000422591 Originally published in: Chemoecology 14(3-4), http://doi.org/10.1007/s00049-004-0281-5 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Chemoecology14:217–223 (2004) 0937–7409/04/040217–7 CHEMOECOLOGY © Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2004 DOI 10.1007/s00049-004-0281-5 Identification, synthesis and activity of sex pheromone gland components of the autumn gum moth (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), a defoliator of Eucalyptus Martin J. Steinbauer1, Fredrik Östrand2, Tom E. Bellas3, Anna Nilsson4, Fredrik Andersson4, Erik Hedenström4, Michael J. Lacey3 and Florian P. Schiestl5,6 1Co-operative Research Centre (CRC) for Sustainable Production Forestry and CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 2Chemical Ecology and Ecotoxicology, Department of Ecology, Lund University, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden 3CSIRO Entomology, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 4Department of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Mid Sweden University, SE-851 70 Sundsvall, Sweden 5Department of Evolutionary Biology, University of Vienna and School of Botany and Zoology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 6Present address: Geobotanical Institute ETH, 107 Zollikerstrasse, CH-8008 Zürich, Switzerland Summary. The autumn gum moth, Mnesampela privata Introduction (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), is native to Australia and can be a pest of plantation eucalypts. -

1 General Introduction

1 General Introduction If the karate-ka (student) shall walk the true path, first he will cast aside all preference. Tatsuo Shimabuku, Grand Master of Isshin-ryu Karate 1.1 The Importance of Insects ~30% of the plants we grow for food and materials. Because of their great numbers and diversity, insects Insects transmit some of these pathogens. While have a considerable impact on human life and indus- weeds can often reduce pest attack, they can also try, particularly away from cities and in the tropics. harbour the pest’s enemies or provide alternative On the positive side they form a large and irreplace- resources for the pest itself. Then in storage, insects, able part of the ecosystem, especially as pollinators mites, rodents and fungi cause a further 30% loss. of fruit and vegetable crops and, of course, many Apart from such biotic damage, severe physical con- wild plants (Section 8.2.1). They also have a place ditions such as drought, storms and flooding cause in soil formation (Section 8.2.4) and are being used additional losses. For example, under ideal field increasingly in ‘greener’ methods of pest control. conditions new wheat varieties (e.g. Agnote and Biological control using insects as predators and Humber) would give yields of ~16 tonnes/ha, but parasites of pest insects has been developed in the produce typically about half this under good hus- West for over a century, and much longer in China. bandry. Pre-harvest destruction due only to insects More recently integrated pest management (IPM) is 10–13% (Pimentel et al., 1984; Thacker, 2002). -

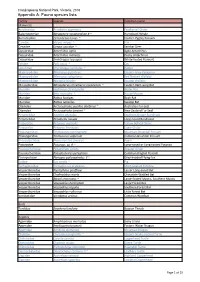

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

01/02 Annual Report (PDF, 6741KB)

M 56 CBC for Sustarnable Production Forestry — Annual Report 2001/02 Publications Genetic Improvement Program McGowen MH, Wiltshire RJ, Potts BM, Vaillancourt RE (2001). The origin of Eucalyptus vernicosa, a Books and book chapters unique shrub eucalypt. Biological Journal of the Auckland LD, Bui T, Zhou Y, Shepherd M, Williams CG Linnean Society 74, 397-405. (2002). Transpecific recovery of pine microsatellite. In ‘Conifer Microsatellite Handbook’. (Eds CG Williams McKinnon GE, Vaillancourt RE, Tilyard PA, Potts BM and LD Auckland) pp. 27-28. (Texas A & M University: (2001). Maternal inheritance of the chloroplast genome College Station, Texas, USA) in Eucalyptus globulus and interspecific hybrids, Genome 44, 831-835. Refereed publications Costa e Silva J, Dutkowski GW, Gilmour AR (2001). Patterson B, Vaillancourt RE, Potts BM (2001). Analysis of early tree height in forest genetic trials is Eucalypt seed collectors: beware of sampling seedlots enhanced by including a spatially correlated residual. from low in the canopy! Australian Forestry 64, 139- Canadian Journal of Forest Research 31, 1887-1893. 142. Dungey HS, Potts BM (2002). Susceptibility of Potts BM, Potts WC, Kantvilas G (2001). The Miena some Eucalyptus species and their hybrids to possum cider gum, Eucalyptus gunnii subsp. (livaricata damage. Australian Forestry 65, 16-23. (Myrtaceae): a taxon in rapid decline. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 135, 57-6l. Freeman JS, Jackson HD, Steane DA, McKinnon GE, Dutkowski GW, Potts BM, Vaillancourt RE (2001). Pound LM, Wallwork MAB, Potts BM, Sedgley M _iii_.-_,_ Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of Eucalyptus (2002). Self-incompatibility in Eucalyptus globulus globulus. Australian Journal ofBotany 49, 585-589. -

Eucalyptus Species for Taranaki

Eucalyptus Species for Taranaki 14 Introduction conditions. Especially suited to saline winds. This This information sheet follows on from the information species holds its form, mills extremely well at a young sheet, ‘Eucalyptus’ (No.13), which discusses general age, and is largely unaffected by pests and diseases. management issues such as siting, selecting tree stocks, Eucalyptus nitens shining gum E. nitens is more tolerant planting regimes, silviculture, establishment, weed to wet sites and is suited to planting in all damper sites control, planting technique, fertiliser requirements, and that E. fraxinoides won't tolerate, for example, low lying pest and disease control. damper areas along streambanks and on hillsites affected by springs. It is also equally suited to drier As no one species of eucalypt will thrive over the range 'fraxinoides' sites. Generally, E. nitens is suited to of sites in a similar manner to Pinus radiata, selecting the planting in soils that are a bit damper than pine will most suitable species for a particular site is of critical tolerate. Furthermore, the tree has good form, a fast importance. Species selection is just as important, if not growth rate, and is resistant to cold. It has a good more, than issues associated with their subsequent reputation for milling and exceptional peeling management. properties (better than radiata pine), although more trial work on drying properties is required. E. nitens A lack of objective, accessible, practical local knowledge used to be affected by the paropsis tortoise beetle and experience of eucalypt growing in Taranaki makes (Paropsis charybdis), but since that beetle has been it difficult for people seeking advice on correct species controlled, the species is largely free of pest and disease to plant. -

List of Moth Species April Lightsheet

Moth species recorded during April 2019 lightsheet Abantiades aphenges Glyphidoptera polymita Pernattia pusilla Abantiades hyalinatus Halone sejuncta Plesanemma fucata Abantiades labyrinthicus Halone sejuncta Poecilasthena pulchraria Achyra affinitalis Hednota sp. Pollanisus sp. Agriophara sp. Hellula hydralis Proteuxoa sp. Alapadna pauropis Hypobapta tachyhalotaria Proteuxoa tortisigna Anthela varia Idea costaria Pseudanapaea transvestita Arrade leucocosmalis Labdia chryselectra Psilosticha sp. Asura lydia Lecithocera imprudens Pterolocera leucocera Capusa sp. Lepidoscia characota Rhuma sp. Catoryctis subparallela Lepidoscia sp. Scioglyptis chionomera Chenuala heliapsis Lichenaula tholodes Scoliacma nana Chiriphe dichotoma Limnaecia camptosema Scoparia exhibitalis Chloroclystis metallospora Limnaecia sp. Softa concavata Chlorocoma dichloraria Lychnographa agaura Stathmopoda sp. Chlorocoma sp. Macrobathra chrysotoxa Stibaroma sp. Chlorocoma stereota Macrobathra desmotoma Syneora euboliaria Circopetes obtusata Metasia capnochroa Termessa gratiosa Cosmodes elegans Microdes squamulata Thalaina clara Crocanthes micradelpha Mimaglossa nauplialis Thalaina selenaea Crypsiphona ocultaria Mnesampela lenae Thallarcha phalarota Cryptoptila australana Monoctenia smerintharia Threnosia heminephes Culladia cuneiferellus Monoctenia sp. Thrincophora lignigerana Detounda leptoplasta Monopis crocicapitella Tigrioides alterna Discophlebia sp. Munychryia senicula Tortricinae sp. Dissomorphia australiaria Musotima nitidalis Trichiocercus sparshalli Epidesmia -

Occasional Papers

NUMBER 136, 37 pages 28 August 2020 BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS TAXONOMIC REVISION AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF PHASSODES BETHUNE -B AKER , 1905 (L EPIDOPTERA : H EPIALIDAE ), GHOST MOTH DESCENDANTS OF A SUBDUCTION ZONE WEED IN THE SOUTH -WEST PACIFIC JOHN R. G REHAN & C ARLOS G.C. M IELKE BISHOP MUSEUM PRESS HONOLULU Cover illustration: Selection of scales from central forewing of Phassodes spp. (see page 14). Photos by James Boone, Miho Maeda, and Agnes Stubblefield. Bishop Museum Press has been publishing scholarly books on the natu - ESEARCH ral and cultural history of Hawai‘i and the Pacific since 1892. The R Bishop Museum Occasional Papers (eISSN 2376-3191) is a series of UBLICATIONS OF short papers describing original research in the natural and cultural sci - P ences. BISHOP MUSEUM The Bishop Museum Press also published the Bishop Museum Bulletin series. It was begun in 1922 as a series of monographs presenting the results of research in many scientific fields throughout the Pacific. In 1987, the Bulletin series was superceded by the Museum’s five current monographic series, issued irregularly: Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology (eISSN 2376-3132) Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany (eISSN 2376-3078) Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology (eISSN 2376-3124) Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology (eISSN 2376-3213) Bishop Museum Bulletins in Cultural and Environmental Studies (eISSN 2376-3159) To subscribe to any of the above series, or to purchase individual publi - cations, please write to: Bishop Museum Press, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-2704, USA. Phone: (808) 848-4135. Email: [email protected]. BERNICE PAUAHI BISHOP MUSEUM The State Museum of Natural and Cultural History eISSN 2376-3191 1525 Bernice Street Copyright © by Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-2704, USA Published online: 28 August 2020 ISSN (online) 2376-3191 Taxonomic revision and biogeography of Phassodes Bethune-Baker, 1905 (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae), ghost moth descendants of a subduc - tion zone weed in the south-west Pacific. -

The World's First Inquiline Flatid

TABLE OF CONTENTS KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Deep transcriptome insights into cave beetle eyes 1 Marcus Friedrich Aedes control: the future is now! 2 Hoffmann, A.A. The Hemipteroid Tree of Life 3 Kevin P. Johnson Biosecurity in northern Australia 4 James A. Walker Seeing at the limits: vision and visual navigation in nocturnal insects 5 Eric Warrant ORAL PRESENTATIONS Dung beetle (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae) abundance and diversity at nature preserve within hyper-arid ecosystem of Arabian Peninsula 6 Abdel-Dayem, M., Kondratieff, B., Fadl , H.(1) and Aldhafer, H. Screening of sugarcane cultivars to assess the incidence against Chilo infuscatellus (Pyralidae, Lepidoptera) 6 Ahmad, S., Qurban, A. and Zahid, A. Microbiology and nutritional composition of some edible insects 7 Amadi, E.N. Studies on the mopane worm, Imbrasia belina an edible caterpillar 7 Allotey, J. DNA barcoding identification of mosquitoes using traditional and next-generation sequencing techniques 8 Batovska, J., Lynch, S., Cogan, N., Brown, K. and Blacket, M.J. Towards a compelling phylogeny of cyclorrhaphan flies (Diptera) using whole body adult transcriptomes 9 Bayless, K.M., Trautwein, M.D., Meusemann, K., Yeates, D.K. and Wiegmann, B.M. Establishing a population genetics toolbox and regional spatial database to facilitate identfying the incursion origin of the dengue mosquito Aedes aeqypti and the Asian tiger Ae. albopictus 10 Beebe, N.W. A summary of interceptions and additions to the New Zealand fauna, with reference to Australian origins 11 Bennett, S.J. The role of nutrition in determining individual and group patterns of behaviour 12 Berville, L., Hoffmann, B. and Suarez, A. Australian millipede diversity: an update 13 Black, D.