Northwestern Salamander Taxonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon

INFORMATION REPORTS NUMBER 2010-05 FISH DIVISION Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife prohibits discrimination in all of its programs and services on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against as described above in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information, please contact ADA Coordinator, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 3406 Cherry Drive NE, Salem, OR, 503-947-6000. This material will be furnished in alternate format for people with disabilities if needed. Please call 541-757-4263 to request 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Sharon E. Tippery Brian L. Bangs Kim K. Jones Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Corvallis, OR November, 2010 This project was financed with funds administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service State Wildlife Grants under contract T-17-1 and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Plan for Salmon and Watersheds. Citation: Tippery, S. E., B. L Bangs and K. K. Jones. 2010. 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon. Information Report 2010-05, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Corvallis. CONTENTS FIGURES....................................................................................................................................... -

2009 Amphibian Surveys

Amphibians in the City Presence, Influential Factors, and Recommendations in Portland, OR Katie Holzer City of Portland Bureau of Parks and Recreation Bureau of Environmental Services August 2009 Introduction Background We are currently in the midst of the largest extinction of species on Earth in 65 million years (Myers & Knoll 2001, Baillie et al. 2004). Although this crisis is affecting nearly all taxa, amphibians are being hit particularly strongly, as one in three amphibian species are threatened with extinction (Pounds et al. 2006). Amphibians comprise frogs, salamanders, and caecilians, but in the Pacific Northwest of the United States we have only frogs and salamanders. There are some unique amphibian characteristics that are likely contributing to their rapid decline: 1) Amphibians have moist, permeable skin that makes them sensitive to pollution and prone to drying out (Smith & Moran 1930). 2) Many amphibians require multiple specific habitats such as ponds for egg laying and forests for the summer dry months. These habitats must be individually suitable for amphibians as well as connected to each other for populations to be successful (Bowne & Bowers 2004). 3) Many amphibians exhibit strong site fidelity where they will attempt to return to the same area again and again, even if the area is degraded and/or new areas are constructed (Stumpel & Voet 1998). 4) Chytridiomycota is a fungus that is transmitted by water and is rapidly sweeping across the globe taking a large toll on amphibians (Retallick et al., 2004). The fungus infects the skin of amphibians and has recently arrived in the Pacific Northwest. All of these factors are contributing to the sharp decline of amphibian populations around the world. -

Apparent Predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus Canadensis, on Long-Toed Salamanders, Ambystoma Macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range

Notes Apparent Predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus canadensis, on Long-toed Salamanders, Ambystoma macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range MICHAEL P. M URRAY1,CHRISTOPHER A. PEARL2, and R. BRUCE BURY2 1 Crater Lake National Park, P.O. Box 7, Crater Lake, Oregon 97604 USA (e-mail: [email protected]). Author for correspondence 2 USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 USA Murray, Michael P., Christopher A. Pearl, and R. Bruce Bury. 2005. Apparent predation by Gray Jays, Perisoreus canadensis, on Long-toed Salamanders, Ambystoma macrodactylum, in the Oregon Cascade Range. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(2): 291-292. We report observations of Gray Jays (Perisoreus canadensis) appearing to consume larval Long-toed Salamanders (Ambystoma macrodactylum) in a drying subalpine pond in Oregon, USA. Corvids are known to prey upon a variety of anuran amphibians, but to our knowledge, this is the first report of predation by any corvid on aquatic salamanders. Long-toed Salamanders appear palatable to Gray Jays, and may provide a food resource to Gray Jays when salamander larvae are concentrated in drying temporary ponds. Key Words: Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis, Long-toed Salamander, Ambystoma macrodactylum, amphibian, corvid, diet, larvae, pond. Corvid birds are generalist feeders and “oppor- vations, the pond had dried to a small pool (approxi- tunistic” predators (Bent 1946; Marshall et al. 2003). In mately 40 m2) which was about 5% of the area cov- montane regions of western North America, corvids ered when full. We observed two Gray Jays foraging sometimes consume anuran amphibians, which can at a muddy circular depression (0.3 m diameter) offer a concentrated food resource in breeding or larval located 2 m from the only remaining pool in the pond rearing aggregations (Beiswenger 1981; Olson 1989; basin. -

Spreading Holiday Spirit and Northwestern Salamanders, Ambystoma Gracile (Baird 1859) (Caudata: Ambystomatidae), Across the USA Michael R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 9-2015 Spreading Holiday Spirit and Northwestern Salamanders, Ambystoma gracile (Baird 1859) (Caudata: Ambystomatidae), Across the USA Michael R. Rochford University of Florida, [email protected] Jeffrey M. Lemm San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, [email protected] Kenneth Krysko Florida Museum of Nahral History, Division of Herpetology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, [email protected] Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Robert W. Hansen Clovis, California, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Population Biology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Rochford, Michael R.; Lemm, Jeffrey M.; Krysko, Kenneth; Somma, Louis A.; Hansen, Robert W.; and Mazzotti, Frank J., "Spreading Holiday Spirit and Northwestern Salamanders, Ambystoma gracile (Baird 1859) (Caudata: Ambystomatidae), Across the USA" (2015). Papers in Herpetology. 15. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Michael R. Rochford, Jeffrey M. Lemm, Kenneth Krysko, Louis A. Somma, Robert W. Hansen, and Frank J. Mazzotti This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/15 WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS IRCF REPTILES • VOL15, & NAMPHIBIANSO 4 • DEC 2008 •189 22(3):126–127 • SEP 2015 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCED SPECIES FEATURE ARTICLES . -

Amphibians in Managed Woodlands: Tools for Family Forestland Owners

Woodland Fish & Wildlife • 2017 Amphibians in Managed Woodlands Tools for Family Forestland Owners Authors: Lauren Grand, OSU Extension, Ken Bevis, Washington Department of Natural Resources Edited by: Fran Cafferata Coe, Cafferata Consulting Pacific Tree (chorus) Frog Introduction good indicators of habitat quality (e.g., Amphibians are among the most ancient habitat diversity, habitat connectivity, water vertebrate fauna on earth. They occur on all quality). Amphibians also play a key role in continents, except Antarctica, and display a food webs and nutrient cycling as they are dazzling array of shapes, sizes and adapta- both prey (eaten by fish, mammals, birds, tions to local conditions. There are 32 species and reptiles) and predators (eating insects, of amphibians found in Oregon and Wash- snails, slugs, worms, and in some cases, ington. Many are strongly associated with small mammals). The presence of forest freshwater habitats, such as rivers, streams, salamanders has also been positively cor- wetlands, and artificial ponds. While most related to soil building processes (Best and amphibians spend at least part of their life- Welsh 2014). cycle in water, some species are fully terres- Landowners can promote amphib- trial, spending their entire life-cycle on land ian habitat on their property to improve or in the ground, generally utilizing moist overall ecosystem health and to support areas within forests (Corkran and Thoms the species themselves, many of which 2006, Leonard et. al 1993). have declining or threatened populations. The following sections of this publica- Photo by Kelly McAllister. Amphibians are of great ecological impor- tance and can be found in all forest age tion describe amphibian habitats, which classes. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

July to December 2019 (Pdf)

2019 Journal Publications July Adelizzi, R. Portmann, J. van Meter, R. (2019). Effect of Individual and Combined Treatments of Pesticide, Fertilizer, and Salt on Growth and Corticosterone Levels of Larval Southern Leopard Frogs (Lithobates sphenocephala). Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 77(1), pp.29-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31020372 Albecker, M. A. McCoy, M. W. (2019). Local adaptation for enhanced salt tolerance reduces non‐ adaptive plasticity caused by osmotic stress. Evolution, Early View. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/evo.13798 Alvarez, M. D. V. Fernandez, C. Cove, M. V. (2019). Assessing the role of habitat and species interactions in the population decline and detection bias of Neotropical leaf litter frogs in and around La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica. Neotropical Biology and Conservation 14(2), pp.143– 156, e37526. https://neotropical.pensoft.net/article/37526/list/11/ Amat, F. Rivera, X. Romano, A. Sotgiu, G. (2019). Sexual dimorphism in the endemic Sardinian cave salamander (Atylodes genei). Folia Zoologica, 68(2), p.61-65. https://bioone.org/journals/Folia-Zoologica/volume-68/issue-2/fozo.047.2019/Sexual-dimorphism- in-the-endemic-Sardinian-cave-salamander-Atylodes-genei/10.25225/fozo.047.2019.short Amézquita, A, Suárez, G. Palacios-Rodríguez, P. Beltrán, I. Rodríguez, C. Barrientos, L. S. Daza, J. M. Mazariegos, L. (2019). A new species of Pristimantis (Anura: Craugastoridae) from the cloud forests of Colombian western Andes. Zootaxa, 4648(3). https://www.biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.4648.3.8 Arrivillaga, C. Oakley, J. Ebiner, S. (2019). Predation of Scinax ruber (Anura: Hylidae) tadpoles by a fishing spider of the genus Thaumisia (Araneae: Pisauridae) in south-east Peru. -

Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska

8 — Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S. O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook Special Publication Number 8 The Museum of Southwestern Biology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 2007 Haines, Fort Seward, and the Chilkat River on the Looking up the Taku River into British Columbia, 1929 northern mainland of Southeast Alaska, 1929 (courtesy (courtesy of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collec- of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collection, U.S. tion, U.S. Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-135). Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-107). ii Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. © 2007 The Museum of Southwestern Biology, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publication, Number 8 MAMMALS AND AMPHIBIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA By: S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. (Special Publication No. 8, The Museum of Southwestern Biology). ISBN 978-0-9794517-2-0 Citation: MacDonald, S.O. and J.A. Cook. 2007. Mammals and amphibians of Southeast Alaska. The Museum of Southwestern Biology, Special Publication 8:1-191. The Haida village at Old Kasaan, Prince of Wales Island Lituya Bay along the northern coast of Southeast Alaska (undated photograph courtesy of the Alaska State Library in 1916 (courtesy of the Alaska State Library Place File Place File Collection, Winter and Pond, Kasaan-04). Collection, T.M. Davis, LituyaBay-05). iii Dedicated to the Memory of Terry Wills (1943-2000) A life-long member of Southeast’s fauna and a compassionate friend to all. -

Other Species and Biodiversity of Older Forests

Synthesis of Science to Inform Land Management Within the Northwest Forest Plan Area Chapter 6: Other Species and Biodiversity of Older Forests Bruce G. Marcot, Karen L. Pope, Keith Slauson, findings on amphibians, reptiles, and birds, and on selected Hartwell H. Welsh, Clara A. Wheeler, Matthew J. Reilly, carnivore species including fisher Pekania( pennanti), and William J. Zielinski1 marten (Martes americana), and wolverine (Gulo gulo), and on red tree voles (Arborimus longicaudus) and bats. Introduction We close the section with a brief review of the value of This chapter focuses mostly on terrestrial conditions of spe- early-seral vegetation environments. We next review recent cies and biodiversity associated with late-successional and advances in development of new tools and datasets for old-growth forests in the area of the Northwest Forest Plan species and biodiversity conservation in late-successional (NWFP). We do not address the northern spotted owl (Strix and old-growth forests, and then review recent and ongoing occidentalis caurina) or marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus challenges and opportunities for ameliorating threats marmoratus)—those species and their habitat needs are and addressing dynamic system changes. We end with a covered in chapters 4 and 5, respectively. Also, the NWFP’s set of management considerations drawn from research Aquatic and Riparian Conservation Strategy and associated conducted since the 10-year science synthesis and suggest fish species are addressed in chapter 7, and early-succes- areas of further study. sional vegetation and other conditions are covered more in The general themes reviewed in this chapter were chapters 3 and 12. guided by a set of questions provided by the U.S. -

LONG-TOED SALAMANDER Ambystoma Macrodactylum

LONG-TOED SALAMANDER Ambystoma macrodactylum Photo by Joshua Ream Photo from californiaherps.com Photo by Joshua Ream DISTRIBUTION Alaska Herpetological Society The Long-toed Salamander is widely distributed in northwestern North America. The extent of its The Alaska Herpetological Society is a nonprofit distribution in northern British Columbia is not organization dedicated to advancing the field of known, but it has been found in the Stikine and Herpetology in the State of Alaska. Our mission is Taku watersheds in the Province and in Southeast to promote sound research and management of Alaska, where it has been reported near the mouth amphibians and reptiles in the North and to provide of the Stikine River at Figure Eight Lake (Twin opportunities in outreach, education, and citizen Lakes), Mallard Slough, Cheliped Bay, Andrew science for individuals who are interested in these Slough, Farm Island, and farther out from the river species. delta on Sokolof Island. The species has also been Photo by Joshua Ream collected on the Alaska side of the Coast Range in † INFORMATION ¢ the Taku River valley. This information on the Long-toed Salamander When threatened the tail is raised, head becomes WEB: (Ambystoma macrodactylum) has been provided by tucked, and a sticky white excretion exudes from WWW.AKHERPSOCIETY.ORG the Alaska Herpetological Society. the tail as it is waved about. Up to 14 individuals have been found hibernating communally in gravel FACEBOOK: You can help locate this species on our website, substrate below frost line. ALASKA HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY via a voucher or via the epicollect app. See (Information cited: www.alaskaherps.info / S. -

Northwestern Salamander

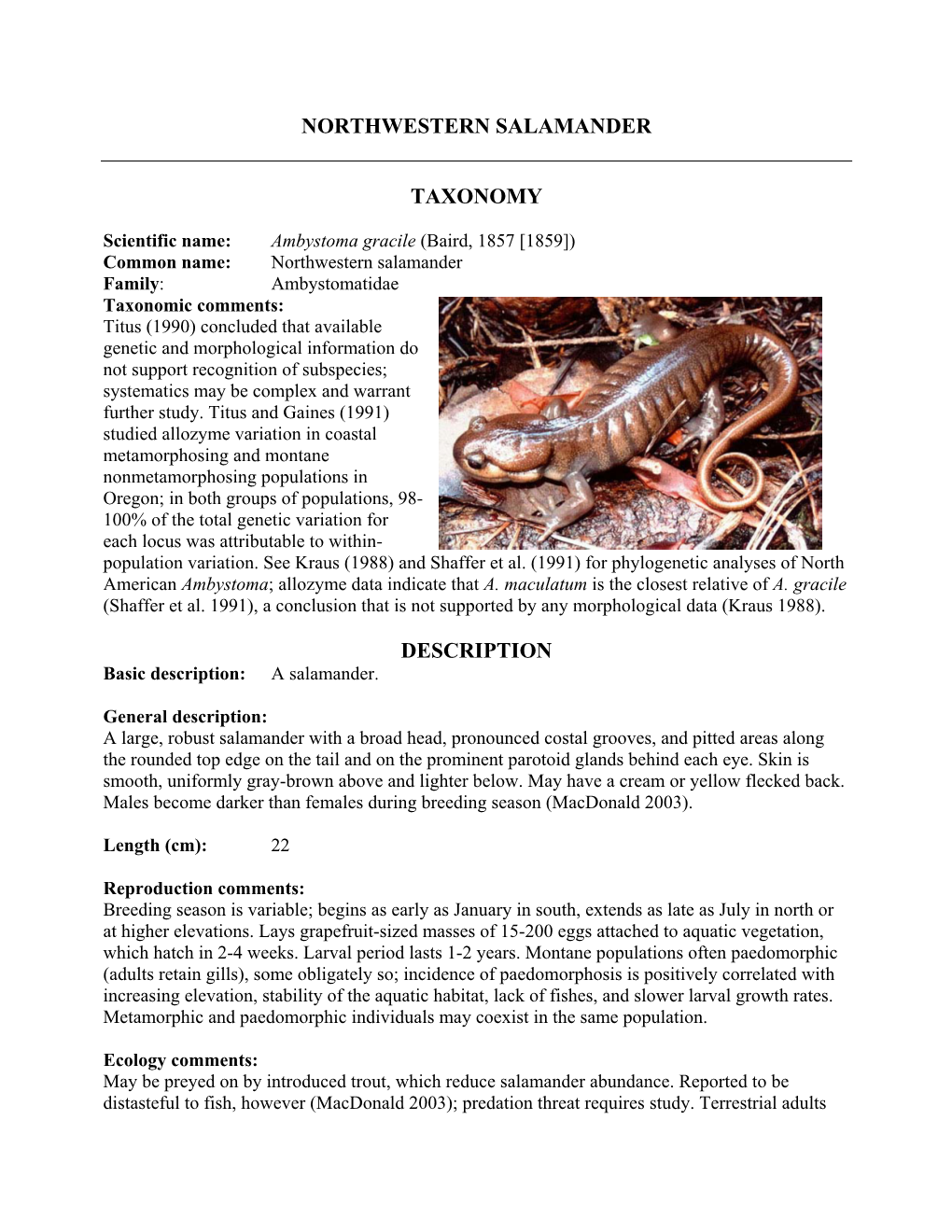

NORTHWESTERN SALAMANDER Ambystoma gracile Photo From Flickr.com Photo from kwiaht.com Photo from flickr.com DISTRIBUTION Alaska Herpetological Society The Northwester Salamander ranges along the Pacific Coast from extreme northern California to The Alaska Herpetological Society is a nonprofit Southeast Alaska, where it has been collected at organization dedicated to advancing the field of only two localities: southeast of Ketchikan on Mary Herpetology in the State of Alaska. Our mission is Island, and northwest of Chichagof Island near to promote sound research and management of Pelican. The only other record was a globular egg amphibians and reptiles in the North and to provide mass, presumably of this species, found in Figure opportunities in outreach, education, and citizen Eight Lake, Stikine River, on June 21, 1991. science for individuals who are interested in these species. When molested, this species assumes an elevated- Photo from Seattle.gov tail pose and secretes a white, milky fluid from its grandular areas. This secretion may cause skin † INFORMATION ¢ irritation in some people. Some salamanders may also make a series of ticking sounds when WEB: This information on the Northwestern Ambystoma gracile) disturbed. WWW.AKHERPSOCIETY.ORG Salamander ( has been provided by the Alaska Herpetological Society. Two subspecies are generally recognized; one You can help locate this species on our website, occurs in Alaska. Some authors suggest subspecific FACEBOOK: via a voucher or via the epicollect app. See recognition is not warranted, whereas other suspect ALASKA HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.akherpsociety.org for more information. these populations may represent separate species. (Information cited: www.alaskaherps.info / S. -

Native Amphibians – Introduction Six Species of Amphibians Are Considered Native to Alaska

Appendix 4, Page 127 Native Amphibians – Introduction Six species of amphibians are considered native to Alaska. These are the Western Toad (Bufo boreas), Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica), Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris), Rough-skinned Newt (Taricha granulosa), Long-toed Salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) and Northwestern Salamander (Ambystoma gracile). Only two of these species have been documented outside the southeast regions of the state. The Wood Frog, which is the most hardy and widespread species of frog in North America, has been found from the mainland of Southeast Alaska northward to the Brooks Range. Alaska’s single toad species, the Western Toad, has been recorded throughout the southeast Panhandle and along the mainland coast to Prince William Sound. Many large islands in Southeast Alaska have never been surveyed for amphibians, and only rudimentary species range maps are available for this region. Western Toad and Rough-skinned Newts are thought to be widely distributed throughout the mainland and islands of the Alexander Archipelago. Wood and Spotted Frog and Long-toed Salamander are reported chiefly in areas with transmontane river systems, such as the Taku and Stikine that connect Southeast Alaska to major portions of their distribution in Canada. Northwestern Salamanders are known from only a handful of locations in Southeast Alaska. Southeast Alaska populations of all but Wood Frog are near the northern edges of their geographic ranges. In addition to these native species, two frogs from the Pacific Northwest have been introduced: Pacific Chorus Frog (Pseudacris regilla) and Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora). They apparently have viable but restricted populations in the Alexander Archipelago of Southeast Alaska on Revillagigedo Island and Chichagof Island.