Identifying Washington's Amphibians and Their Egg Masses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wood Frog (Rana Sylvatica): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project March 24, 2005 Erin Muths1, Suzanne Rittmann1, Jason Irwin2, Doug Keinath3, Rick Scherer4 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave. Bldg C, Fort Collins, CO 80526 2 Department of Biology, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837 3 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3381, Laramie, WY 82072 4 Colorado State University, GDPE, Fort Collins, CO 80524 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Muths, E., S. Rittman, J. Irwin, D. Keinath, and R. Scherer. (2005, March 24). Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/woodfrog.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the many people who contributed time and answered questions during our review of the literature. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Erin Muths is a Zoologist with the U.S. Geological Survey – Fort Collins Science Center. She has been studying amphibians in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region for the last 10 years. Her research focuses on demographics of boreal toads, wood frogs and chorus frogs and methods research. She is a principle investigator for the USDOI Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative and is an Associate Editor for the Northwestern Naturalist. Dr. Muths earned a B.S. in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1986); a M.S. in Biology (Systematics and Ecology) from Kansas State University (1990) and a Ph.D. -

2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon

INFORMATION REPORTS NUMBER 2010-05 FISH DIVISION Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife prohibits discrimination in all of its programs and services on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against as described above in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information, please contact ADA Coordinator, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 3406 Cherry Drive NE, Salem, OR, 503-947-6000. This material will be furnished in alternate format for people with disabilities if needed. Please call 541-757-4263 to request 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon Sharon E. Tippery Brian L. Bangs Kim K. Jones Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Corvallis, OR November, 2010 This project was financed with funds administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service State Wildlife Grants under contract T-17-1 and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Plan for Salmon and Watersheds. Citation: Tippery, S. E., B. L Bangs and K. K. Jones. 2010. 2008 Amphibian Distribution Surveys in Wadeable Streams and Ponds in Western and Southeast Oregon. Information Report 2010-05, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Corvallis. CONTENTS FIGURES....................................................................................................................................... -

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Appendix C.5-California Red Legged Frog Report

Appendix C: Biological Resources PROTOCOL-LEVEL CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG SURVEY REPORT FOR THE FORMER SAN LUIS OBISPO TANK FARM SITE (TANK FARM) SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: CHEVRON ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT COMPANY December 2008 C.5-1 Chevron Tank Farm EIR Appendix C: Biological Resources Chevron Tank Farm Site California Red-Legged Frog Survey Report Project No. 0601-3281 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION.................................................... 1 3.0 PROJECT SITE SETTING................................................................................ 1 3.1 EAST BRANCH OF SAN LUIS OBISPO CREEK ................................. 2 3.2 FRESHWATER MARSH ....................................................................... 2 3.3 SEASONAL WET MEADOW................................................................. 3 4.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG LIFE HISTORY....................................... 3 5.0 SURVEY METHODOLOGY .............................................................................. 4 6.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG LITERATURE REVIEW.......................... 5 7.0 FIELD SURVEY RESULTS............................................................................... 7 8.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG PREDATOR CONTROL......................... 10 9.0 CONCLUSION .................................................................................................. 10 -

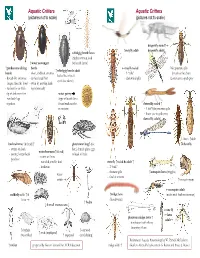

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Successful Reproduction of the Mole Salamander Ambystoma Talpoideum in Captivity, with an Emphasis on Stimuli Environmental Determinants

SHORT NOTE The Herpetological Bulletin 141, 2017: 28-31 Successful reproduction of the mole salamander Ambystoma talpoideum in captivity, with an emphasis on stimuli environmental determinants AXEL HERNANDEZ Department of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Sciences and Technics, University Pasquale Paoli of Corsica, Corte, 20250, France Author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT - Generating and promoting evidence-based husbandry protocols for urodeles, commonly known as newts and salamanders, is urgently needed because most of the up-to-date ex situ programs are focused on frogs and toads than Urodela. Data on biology, life history, ecology and environmental parameters are lacking for many species and are needed to establish suitable husbandry and breeding conditions in captive environments. Two adult females and two adult males, of the mole salamander Ambystoma talpoideum successfully reproduced in captivity. It was found that reproduction of this species depends on various complex stimuli: including natural photoperiod 12:12, rainwater (acidic to neutral pH) and an aquarium full of various debris. Additionally high temperature variations ranging from 2 °C to 17 °C (a decrease followed by an increase) between November and February showed that it is possible to breed adults in aquariums provided the right stimuli are applied at the right moment of time in winter. A. talpoideum shows an explosive breeding mode as previously reported for the whole genus Ambystoma. INTRODUCTION with an emphasis on the environmental determinant stimuli involved. These data may assist in improving breeding these ince the 1980s, the current global amphibian extinction salamanders under artificial conditions. crisis has been discussed and acknowledged (Wake, A. -

Northern Spring Salamander Fact Sheet

WILDLIFE IN CONNECTICUT STATE THREATENED SPECIES © COURTESY D. QUINN © COURTESY Northern Spring Salamander Gyrinophilus p. porphyriticus Background and Range The northern spring salamander is a brightly-colored member of the lungless salamander family (Plethodontidae). True to its name, it resides in cool water springs and streams, making it an excellent indicator of a clean, well- oxygenated water source. Due to its strict habitat and clean water requirements, it is only found in a handful of locations within Connecticut. The Central Connecticut Lowlands divide this amphibian's range into distinct populations. Litchfield and Hartford Counties support the greatest populations of spring salamanders. This salamander is listed as a threatened species in Connecticut. In North America, the spring salamander occurs from extreme southeastern Canada south through New England, west to Ohio, and south down the Appalachians as far as northern Georgia and Alabama. Description This large, robust salamander ranges in color from salmon to reddish-brown to purplish-brown, with a translucent white underbelly. The snout appears “square” when viewed from above and the salamander has well-defined grooves near its eyes to its snout. The tail is laterally flattened with a fin-like tip. Young spring salamanders are lighter in color and have small gills. Their coloration does not have deeper reddish tints until adulthood. Total length ranges from 5 to 7.5 inches. Habitat and Diet Spring salamanders require very clean, cool, and well-oxygenated water. They can be found in streams, brooks, and seepage areas. Preferred habitat lies within steep, rocky hemlock forests. This species is intolerant to disturbances. -

Riparian Management and the Tailed Frog in Northern Coastal Forests

Forest Ecology and Management 124 (1999) 35±43 Riparian management and the tailed frog in northern coastal forests Linda Dupuis*,1, Doug Steventon Centre for Applied Conservation Biology, Department of Forest Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 Ministry of Forests, Prince Rupert Region, Bag 5000, Smithers, BC, Canada V0J 2N0 Received 28 July 1998; accepted 19 January 1999 Abstract Although the importance of aquatic environments and adjacent riparian habitats for ®sh have been recognized by forest managers, headwater creeks have received little attention. The tailed frog, Ascaphus truei, inhabits permanent headwaters, and several US studies suggest that its populations decline following clear-cut logging practices. In British Columbia, this species is considered to be at risk because little is known of its abundance, distribution patterns in the landscape, and habitat needs. We characterized nine logged, buffered and old-growth creeks in each of six watersheds (n 54). Tadpole densities were obtained by area-constrained searches. Despite large natural variation in population size, densities decreased with increasing levels of ®ne sediment (<64 mm diameter), rubble, detritus and wood, and increased with bank width. The parameters that were correlated with lower tadpole densities were found at higher levels in clear-cut creeks than in creeks of other stand types. Tadpole densities were signi®cantly lower in logged streams than in buffered and old-growth creeks; thus, forested buffers along streams appear to maintain natural channel conditions. To prevent direct physical damage and sedimentation of channel beds, we suggest that buffers be retained along permanent headwater creeks. Creeks that display characteristics favoring higher tadpole densities, such as those that have coarse, stable substrates, should have management priority over less favorable creeks. -

AMPHIBIANS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION

AMPHIBIANS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION Amphibians are typically shy, secre- Unlike reptiles, their skin is not scaly. Amphibian eggs must remain moist if tive animals. While a few amphibians Nor do they have claws on their toes. they are to hatch. The eggs do not have are relatively large, most are small, deli- Most amphibians prefer to come out at shells but rather are covered with a jelly- cately attractive, and brightly colored. night. like substance. Amphibians lay eggs sin- That some of these more vulnerable spe- gly, in masses, or in strings in the water The young undergo what is known cies survive at all is cause for wonder. or in some other moist place. as metamorphosis. They pass through Nearly 200 million years ago, amphib- a larval, usually aquatic, stage before As with all Ohio wildlife, the only ians were the first creatures to emerge drastically changing form and becoming real threat to their continued existence from the seas to begin life on land. The adults. is habitat degradation and destruction. term amphibian comes from the Greek Only by conserving suitable habitat to- Ohio is fortunate in having many spe- amphi, which means dual, and bios, day will we enable future generations to cies of amphibians. Although generally meaning life. While it is true that many study and enjoy Ohio’s amphibians. inconspicuous most of the year, during amphibians live a double life — spend- the breeding season, especially follow- ing part of their lives in water and the ing a warm, early spring rain, amphib- rest on land — some never go into the ians appear in great numbers seemingly water and others never leave it. -

Thurston County Species List

Washington Gap Analysis Project 202 Species Predicted or Breeding in: Thurston County CODE COMMON NAME Amphibians RACAT Bullfrog RHCAS Cascade torrent salamander ENES Ensatina AMMA Long-toed salamander AMGR Northwestern salamander RAPR Oregon spotted frog DITE Pacific giant salamander PSRE Pacific treefrog (Chorus frog) RAAU Red-legged frog TAGR Roughskin newt ASTR Tailed frog PLVA Van Dyke's salamander PLVE Western redback salamander BUBO Western toad Birds BOLE American bittern FUAM American coot COBR American crow CIME American dipper CATR American goldfinch FASP American kestrel TUMI American robin HALE Bald eagle COFA Band-tailed pigeon HIRU Barn swallow STVA Barred owl CEAL Belted kingfisher THBE Bewick's wren PAAT Black-capped chickadee PHME Black-headed grosbeak ELLE Black-shouldered kite (White-tailed kite DENI Black-throated gray warbler DEOB Blue grouse ANDI Blue-winged teal EUCY Brewer's blackbird CEAM Brown creeper MOAT Brown-headed cowbird PSMI Bushtit CACAL California quail BRCA Canada goose VISO Cassin's vireo (Solitary vireo) BOCE Cedar waxwing PARU Chestnut-backed chickadee SPPA Chipping sparrow NatureMapping 2007 Washington Gap Analysis Project ANCY Cinnamon teal HIPY Cliff swallow TYAL Common barn-owl MERME Common merganser CHMI Common nighthawk COCOR Common raven GAGA Common snipe GETR Common yellowthroat ACCO Cooper's hawk JUHY Dark-eyed (Oregon) junco PIPU Downy woodpecker STVU European starling COVE Evening grosbeak PAIL Fox sparrow ANST Gadwall AQCH Golden eagle RESA Golden-crowned kinglet PECA Gray jay ARHE Great -

Habitat Use of Amphibians in Southeast Alaska

Discovery Southeast Founded in 1989 in Juneau and serving communities throughout Southeast Alaska, Discovery Southeast is a nonprofit organization that promotes direct, hands-on learning from nature through natural science and outdoor education programs for youth and adults, students and teachers. Discovery Southeast naturalists aim to deepen the bonds between people and nature. (907) 463-1500 fax 463-1587 [email protected] www.discoverysoutheast.org PO Box 21867 Juneau, AK 99802 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 2 1 Methods ....................................................................................................... 5 Initial pond mapping with GIS and photointerpretation ................................ 5 Selection of study ponds ............................................................................. 6 Pond habitat assessments .......................................................................... 8 Amphibian surveys .....................................................................................10 Temperature loggers ..................................................................................13 Atlas of SE Alaskan amphibian records ....................................................15 2 Juneau area breeding pond survey .........................................................17 3 Aquatic vegetation ....................................................................................21 Submerged .................................................................................................21 -

I Found a Frog…

I Found a Frog…What Do I Do With It? Finding a frog or toad in your backyard is a great discovery, especially if you live in an urban setting where these creatures are rarely found. Unless you have a large pond, most frogs and toads we find are transients taking up temporary residence where food and habitat seem good. But when autumn rolls around, starts to cool off, and the frog has not left, what do you do with your little friend? Here is some advice: Does this mean I have a new pet frog or toad? No! Please do not take in the animal. Not only is this illegal, but this is a wild animal that will not do well in a captive environment. Also, the proper artificial habitat is expensive, combined with the cost of food for the winter. And if you get attached to the animal (which is difficult not to do), it will be more difficult to release it in the spring. Many of the animal’s special survival skills will be lost in captivity over the winter. Frogs and toads hibernate in the winter, and rest their bodies for the following summer season. Frogs will want to slow down as daytime temperatures and lengths decrease, but it is not cool enough in our homes to lower metabolic rates. As a result, the frog remains active, will not eat, and will slowly starve. Some frogs with specialized care and live food will change their natural cycles and begin to feed, but if yours does not, it will die unnecessarily.