Download Liner Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Five Dimensions of Homeland and International Security

Five Dimensions of Homeland and International Security Edited by Esther Brimmer Brimmer, Esther, ed., Five Dimensions of Homeland and International Security (Washington, D.C.: Center for Transatlantic Relations, 2008). © Center for Transatlantic Relations, The Johns Hopkins University 2008 Center for Transatlantic Relations The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies The Johns Hopkins University 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 525 Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel. (202) 663-5880 Fax (202) 663-5879 Email: transatlantic @ jhu.edu http://transatlantic.sais-jhu.edu ISBN 10: 0-9801871-0-9 ISBN 13: 978-0-9801871-0-6 This publication is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through a grant ( N00014-06-1-0991) awarded to the National Center for Study of Preparedness and Critical Event Response (PACER) at the Johns Hopkins University. Any opinions, finding, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not represent the policy or position of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Cover Image: In mathematical fractals, images display the same characteristics at different scales. Similarly, there may be connections among security issues although they occur at different levels of “magnification” (local, national, international). Image used with permission of Dave Massey, available at www.free-background-wallpaper.com. Table of Contents Acknowledgements . v Introduction: Five Dimensions of Homeland and International Security . 1 Esther Brimmer and Daniel S. Hamilton Chapter 1 The International Aspects of Societal Resilience: Framing the Issues . 15 Sir David Omand Chapter 2 Chemical Weapons Terrorism: Need for More Than the 5Ds . 29 Amy Sands and Jennifer Machado Chapter 3 Reviving Deterrence . -

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again 2011 Ryan Center Conference Taylor Worley, PhD Assistant Professor of Christian Thought & Tradition 1 Why re-read OT history? 2 Why re-read OT history? There’s so much more to discover there. It’s the key to reading the New Testament better. There’s transformation to pursue. 3 In both the domains of nature and faith, you will find the most excellent things are the deepest hidden. Erasmus, The Sages, 1515 4 “Then he said to them, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.’” Luke 24:44 5 God wishes to move the will rather than the mind. Perfect clarity would help the mind and harm the will. Humble their pride. Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1669 6 Familiar Approaches: Humanize the story to moralize the characters. Analyze the story to principalize the result. Allegorize the story to abstract its meaning. 7 Genesis 22: A Case Study 8 After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here am I.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” “By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17 I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. -

A President's Jeremiad of Terror (Excerpts from Honors Thesis, the Rhetoric of the War on Terror: George W

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 6 Article 6 2006 A President's Jeremiad of Terror (Excerpts from Honors Thesis, The Rhetoric of the War on Terror: George W. Bush's Transformation of the Jeremiad) Lauren Alissa Clark Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Lauren Alissa (2006) "A President's Jeremiad of Terror (Excerpts from Honors Thesis, The Rhetoric of the War on Terror: George W. Bush's Transformation of the Jeremiad)," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 6 , Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol6/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Clark: A President's Jeremiad of Terror (Excerpts from Honors Thesis, Th a president’s jeremiad of terror s both governor and president, George W. Bush has always demon- strated religious devotion in his public rhetoric. His language ap- Apears most overtly religious in the defining event of his presidency: the war on terror. Faith and public policy intertwine in Bush’s presidency, pro- viding him with “guidance and wisdom and strength” during a trying time (as qtd. in Viorst 102). God and nation unite in a mission, a mission described and mediated by the president. It is this unique aspect of Bush’s presidency, which bears examining. How does his rhetoric blur the boundaries between public and private faith, religious beliefs and public policy? How does his rhetoric unite these components in his speeches regarding the war on terror? A useful way to answer these questions is to examine his rhetoric through the form of the jeremiad. -

Of Paul Robeson 53

J. Karp: The “Hassidic Chant” of Paul Robeson 53 Performing Black-Jewish Symbiosis: The “Hassidic Chant” of Paul Robeson JONATHAN KARP* On May 9, 1958, the African American singer and political activist Paul Robeson (1898–1976) performed “The Hassidic [sic] Chant of Levi Isaac,” along with a host of spirituals and folk songs, before a devoted assembly of his fans at Carnegie Hall. The “Hassidic Chant,” as Robeson entitled it, is a version of the Kaddish (Memorial Prayer) attributed to the Hasidic rebbe (master), Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev (1740–1810), a piece also known as the “Din Toyre mit Got” (“The Lawsuit with God”). According to tradition, Levi Yizhak had composed the song spontaneously on a Rosh Hashanah as he contemplated the steadfast faith of his people in the face of their ceaseless suffering. He is said to have stood in the synagogue before the open ark where the Torah scrolls reside and issued his complaint directly to God: a gut morgn dir, riboynoy shel oylem; ikh, levi yitzhak ben sarah mi-barditchev, bin gekumen tzu dir mit a din toyre fun dayn folk yisroel. vos host-tu tzu dayn folk yisroel; un vos hos-tu zich ongezetst oyf dayn folk yisroel? A good day to Thee, Lord of the Universe! I, Levi Yitzhak, son of Sarah, from Berditchev, Bring against you a lawsuit on behalf of your People, Israel. What do you have against your People, Israel? Why have your so oppressed your People, Israel?1 After this questioning of divine justice, Levi Yitzhak proceeded to chant the Kaddish in attestation to God’s sovereignty and supremacy. -

Report to the President on 902 Consultations

REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT ON 902 CONSULTATIONS Special Representatives of the United States and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands January 2017 This page intentionally left blank. About the 902 Consultations Between the United States and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands The Covenant to Establish the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Political Union with the United States of America (Covenant) governs relations between the United States and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Section 902 of the Covenant provides that the Government of the United States and the Government of the Northern Mariana Islands “will designate special representatives to meet and consider in good faith such issues affecting the relationship between the Northern Mariana Islands and the United States as may be designated by either Government and to make a report and recommendations with respect thereto.” These intermittent discussions between the United States and the CNMI have become known as 902 Consultations. Beginning in October 2015, the late CNMI Governor Eloy Inos, followed by Governor Ralph Torres in January 2016, requested U.S. President Barack Obama initiate the 902 Consultations process. In May 2016, President Obama designated Esther Kia’aina, the Assistant Secretary for Insular Areas at the U.S. Department of the Interior, as the Special Representative for the United States for 902 Consultations. Governor Ralph Torres was designated the Special Representative for the CNMI. i Special Representatives and Teams of the United States and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Special Representatives Esther P. Kia’aina Ralph DLG. Torres Assistant Secretary for Insular Areas Governor U.S. -

Newsletter SPRING 2017

15 West 16th Street New York, NY 10011-6301 yivo.org · 212.246.6080 Newsletter SPRING 2017 Follow us @YIVOInstitute Letter from the Director » Contact What does Jewish “continuity” mean? During World tel 212.246.6080 War II, YIVO leaders believed that the continuity fax 212.292.1892 of the Jewish people depended on the survival of yivo.org cultural memory, which meant the preservation of General Inquiries the documents and artifacts that recorded Jewish [email protected] history. They risked their lives to preserve these Archival Inquiries artifacts and today YIVO is ensuring their permanent [email protected] preservation through the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Photo/Film Archives | [email protected] Sound Archives | SOUNDARCHIVES YIVO CJH ORG Collections Project. But preservation of documents @ . is not enough. They must be read and understood, Library Inquiries put in context, and given life through narratives. We [email protected] must look toward innovative educational programs, as well as digital means of reaching Jews around the world who have been » Travel Directions cut off from their history, language, and culture by the catastrophes of the The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is located in the Center for Jewish History at 15 West 16th Street between Fifth and 20th century in order to rebuild our understanding of our history and sense Sixth Avenues, New York, NY 10011. of our future. This is YIVO’s challenge. I hope you will join us in meeting it. by subway 14 St / Union Sq. L N Q R 4 5 6 14 St + 6 Ave F L M PATH 18 St + 7 Ave 1 Jonathan Brent 14 St + 7 Ave 1 2 3 14 St + 8 Ave A C E L Executive Director by bus The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is the leading academic center for East » Hours [ CLOSED ON MAJOR FEDERAL AND JEWISH HOLIDAYS ] European and Russian Jewish Studies in the world, specializing in Yiddish language, Gallery Hours Administrative Hours literature, and folklore; the Holocaust; and the American Jewish experience. -

One Hundred Tenth Congress of the United States of America

S. 2739 One Hundred Tenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Thursday, the third day of January, two thousand and eight An Act To authorize certain programs and activities in the Department of the Interior, the Forest Service, and the Department of Energy, to implement further the Act approving the Covenant to Establish a Commonwealth of the Northern Mar- iana Islands in Political Union with the United States of America, to amend the Compact of Free Association Amendments Act of 2003, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. TITLE I—FOREST SERVICE AUTHORIZATIONS Sec. 101. Wild Sky Wilderness. Sec. 102. Designation of national recreational trail, Willamette National Forest, Or- egon, in honor of Jim Weaver, a former Member of the House of Rep- resentatives. TITLE II—BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT AUTHORIZATIONS Sec. 201. Piedras Blancas Historic Light Station. Sec. 202. Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Outstanding Natural Area. Sec. 203. Nevada National Guard land conveyance, Clark County, Nevada. TITLE III—NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AUTHORIZATIONS Subtitle A—Cooperative Agreements Sec. 301. Cooperative agreements for national park natural resource protection. Subtitle B—Boundary Adjustments and Authorizations Sec. 311. Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site boundary adjustment. -

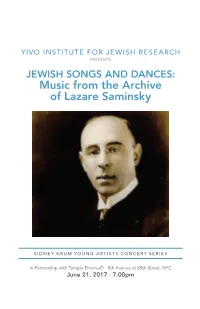

Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky

YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS JEWISH SONGS AND DANCES: Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky SIDNEY KRUM YOUNG ARTISTS CONCERT SERIES In Partnership with Temple Emanu-El · 5th Avenue at 65th Street, NYC June 21, 2017 · 7:00pm PROGRAM The Sidney Krum Young Artists Concert Series is made possible by a generous gift from the Estate of Sidney Krum. In partnership with Temple Emanu-El. Saminsky, Hassidic Suite Op. 24 1-3 Saminsky, First Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 12 1-3 Engel, Omrim: Yeshnah erets Achron, 2 Hebrew Pieces Op. 35 No. 2 Saminsky, Second Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 13 1-3 Saminsky, A Kleyne Rapsodi Saminsky, And Rabbi Eliezer Said Engel, Rabbi Levi-Yitzkah’s Kaddish Achron, Sher Op. 42 Saminsky, Lid fun esterke Saminsky, Shir Hashirim Streicher, Shir Hashirim Engel, Freylekhs, Op. 21 Performers: Mo Glazman, Voice Eliza Bagg, Voice Brigid Coleridge, Violin Julian Schwartz, Cello Marika Bournaki, Piano COMPOSER BIOGRAPHIES Born in Vale-Gotzulovo, Ukraine in 1882, LAZARE SAMINSKY was one of the founding members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg – a group of composers committed to forging a new national style of Jewish classical music infused with Jewish folk melodies and liturgical music. Saminksy’s teachers at the St. Petersburg conservatory included Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov. Fascinated with Jewish culture, Saminsky went on trips to Southern Russia and Georgia to gather Jewish folk music and ancient religious chants. In the 1910s Saminsky spent a substantial amount of time travelling giving lectures and conducting concerts. Saminsky’s travels brought him to Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Paris, and England. -

A. the International Bill of Human Rights

A. THE INTERNATIONAL BILL OF HUMAN RIGHTS 1. Universal Declaration of Human Rights Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948 PREAMBLE Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be pro- tected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the great- est importance for the full realization -

Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Veniamin Basner & Dmitri Shostakovich

“Zun mit a regn” the Jewish element in the music of Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Veniamin Basner & Dmitri Shostakovich from folklore to subversive musical language in the spirit of their friendship Sovali soprano Boris Goldenblank or Grigory Sedukh violin Alexander Oratovski cello Sander Sittig or Paul Prenen piano PROGRAMME Mieczyslaw Weinberg (Moisei Vainberg) (1919-1996) Jewish Songs (Yitschok Leyb Peretz), Op. 13 (1943) arrangement for voice and piano trio by Alexander Oratovski Introduction Breytele (Bread Roll) Viglid (Cradle Song) Der jeger (The Hunter) Oyfn grinem bergele (On the Green Mountain) Der yesoymes brivele (The Orphan’s Letter) Coda Sonata for cello solo, No.1, Op. 72 (1960) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) From Piano Trio No. 2, Op. 67 (1944) 3. Largo 4. Allegretto - intermission - Mieczyslaw Weinberg Jewish Songs (Samuel Galkin), Op. 17 (1944) arrangement for voice and piano trio by Alexander Oratovski Di muter (The Mother) Tsum libn (To Love) Tife griber, royte leym (Deep Graves, Red Earth) Tsu di royte kriger (To the Red Soldier) Veniamin Basner (1925-1996) Poem, Op. 7 No.1 for violin and piano Dmitri Shostakovich Prelude and Fugue No. 8 in F-sharp minor for piano, Op. 87 (1950-51) From Jewish Folk Poetry, Op. 79 (1948) arrangement for voice and piano trio by Alexander Oratovski Zun mit a regn (Sun and Rain) Shlof mayn kind (Sleep My Child) Her zhe, Khashe (Listen, Khashe) Af dem boydem (On the Garret) ------------- 3 Programme notes Zun mit a regn (Sun and Rain) is a metaphor for laughter and tears and part and parcel of Yiddish music. It is the opening line of Shostakovich’s song cylcle From Jewish Folk Poetry and a fitting motto for a programme dedicated to the three Russian composers and friends Mieczyslaw Weinberg (Moisei Vainberg) (1919-1996), Veniamin Basner (1925-1996) and Dimitri Shostakovich (1906- 1975). -

How Well Do You Know Maryland?

1 Table of Contents Contents Welcome to Baltimore Living! ................................................................................................................................................ 3 How Well Do You Know Maryland? ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Things to Do While Living in Baltimore ................................................................................................................................... 5 Off-Campus Conduct ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 Off-Campus Living ................................................................................................................................................................... 9 OFF CAMPUS LIVING SAFETY AND SECURITY TIPS .............................................................................................................. 9 TENANT/LANDLORD RELATIONS AND RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................................................................. 11 BALTIMORE CITY—MAINTENANCE ............................................................................................................................... 12 BALTIMORE COUNTY—MAINTENANCE ........................................................................................................................ 14 STATE—MAINTENANCE ...............................................................................................................................................