Feasibility of Machine Learning Methods for Separating Wood and Leaf Points from Terrestrial Laser Scanning Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synthetic Conversion of Leaf Chloroplasts Into Carotenoid-Rich Plastids Reveals Mechanistic Basis of Natural Chromoplast Development

Synthetic conversion of leaf chloroplasts into carotenoid-rich plastids reveals mechanistic basis of natural chromoplast development Briardo Llorentea,b,c,1, Salvador Torres-Montillaa, Luca Morellia, Igor Florez-Sarasaa, José Tomás Matusa,d, Miguel Ezquerroa, Lucio D’Andreaa,e, Fakhreddine Houhouf, Eszter Majerf, Belén Picóg, Jaime Cebollag, Adrian Troncosoh, Alisdair R. Ferniee, José-Antonio Daròsf, and Manuel Rodriguez-Concepciona,f,1 aCentre for Research in Agricultural Genomics (CRAG) CSIC-IRTA-UAB-UB, Campus UAB Bellaterra, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; bARC Center of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, Department of Molecular Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; cCSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; dInstitute for Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), Universitat de Valencia-CSIC, 46908 Paterna, Valencia, Spain; eMax-Planck-Institut für Molekulare Pflanzenphysiologie, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany; fInstituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Plantas, CSIC-Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; gInstituto de Conservación y Mejora de la Agrodiversidad, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; and hSorbonne Universités, Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Génie Enzymatique et Cellulaire, UMR-CNRS 7025, CS 60319, 60203 Compiègne Cedex, France Edited by Krishna K. Niyogi, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved July 29, 2020 (received for review March 9, 2020) Plastids, the defining organelles of plant cells, undergo physiological chromoplasts but into a completely different type of plastids and morphological changes to fulfill distinct biological functions. In named gerontoplasts (1, 2). particular, the differentiation of chloroplasts into chromoplasts The most prominent changes during chloroplast-to-chromo- results in an enhanced storage capacity for carotenoids with indus- plast differentiation are the reorganization of the internal plastid trial and nutritional value such as beta-carotene (provitamin A). -

Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species

rch: O ea pe es n A R t c s c Rodriguez et al., Forest Res 2016, 5:3 e e r s o s Forest Research F DOI: 10.4172/2168-9776.1000183 Open Access ISSN: 2168-9776 Research Article Open Access Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub Forest and its Significance in Taxonomy and Drought Resistance Rodriguez HG1*, Maiti R1 and Kumari A2 1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo León 67700, México 2Plant Physiology, Agricultural College, Professor Jaya Shankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Polasa, Jagtial, Karimnagar, Telangana, India Abstract The present paper make a synthesis of a comparative leaf anatomy including leaf surface, leaf lamina, petiole and venation as well as wood anatomy of 30 woody species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub, Northeastern Mexico. The results showed a large variability in anatomical traits of both leaf and wood anatomy. The variations of these anatomical traits could be effectively used in taxonomic delimitation of the species and adaptation of the species to xeric environments. For example the absence or low frequency of stomata on leaf surface, the presence of long palisade cells, and presence of narrow xylem vessels in the wood could be related to adaptation of the species to drought. Besides the species with dense venation and petiole with thick collenchyma and sclerenchyma and large vascular bundle could be well adapted to xeric environments. It is suggested that a comprehensive consideration of leaf anatomy (leaf surface, lamina, petiole and venation) and wood anatomy should be used as a basis of taxonomy and drought resistance. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

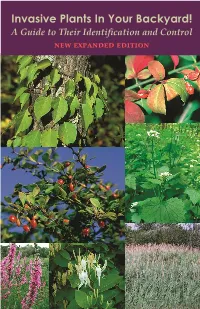

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Tree Identification Guide

2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus monogyna Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus montana Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 2 ‹ ‹ Start here Is the leaf at least -

LESSON 5: LEAVES and TREES

LESSON 5: LEAVES and TREES LEVEL ONE This lesson might also be called “more about the vascular system.” We are going to study leaves, which are part of the vascular system, and trees, whose trunks and bark are also a part of the vascular system. Let’s look at leaves first. There are names for the parts of a leaf: Some of you may be thinking the same thought that our friend is. Why do scientists always have to make things more difficult by using hard words? It’s because science requires precision not just with experiments, but with words, too. Some of the words on the leaf diagram appear in other branches of science, not just botany. For instance, the word “lateral” pops up in many branches of science, and no matter where you see it, it always means “side,” or something having to do with sides. “Apex” always means “tip,” and the word “lamina” always refers to something flat. Leaves come in a great variety of shapes, and botanists have come up with names for all of them. (That’s great news, eh?) Every leaf can be classified as one of these: simple palmate pinnate double pinnate triple pinnate Look carefully at the patterns of the double and triple pinnate leaves. Can you see how the same pattern is repeated? In the triple pinnate leaf, the tiny branches and the intermediate branches have the same pattern as the whole leaf. There are a great variety of simple leaf shapes and some of these shapes don’t look so simple. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

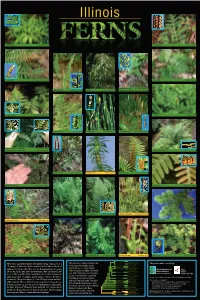

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

PLANT MORPHOLOGY: Vegetative & Reproductive

PLANT MORPHOLOGY: Vegetative & Reproductive Study of form, shape or structure of a plant and its parts Vegetative vs. reproductive morphology http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peanut_plant_NSRW.jpg Vegetative morphology http://faculty.baruch.cuny.edu/jwahlert/bio1003/images/anthophyta/peanut_cotyledon.jpg Seed = starting point of plant after fertilization; a young plant in which development is arrested and the plant is dormant. Monocotyledon vs. dicotyledon cotyledon = leaf developed at 1st node of embryo (seed leaf). “Textbook” plant http://bio1903.nicerweb.com/Locked/media/ch35/35_02AngiospermStructure.jpg Stem variation Stem variation http://www2.mcdaniel.edu/Biology/botf99/stems&leaves/barrel.jpg http://www.puc.edu/Faculty/Gilbert_Muth/art0042.jpg http://www2.mcdaniel.edu/Biology/botf99/stems&leaves/xstawb.gif http://biology.uwsp.edu/courses/botlab/images/1854$.jpg Vegetative morphology Leaf variation Leaf variation Leaf variation Vegetative morphology If the primary root persists, it is called a “true root” and may take the following forms: taproot = single main root (descends vertically) with small lateral roots. fibrous roots = many divided roots of +/- equal size & thickness. http://oregonstate.edu/dept/nursery-weeds/weedspeciespage/OXALIS/oxalis_taproot.jpg adventitious roots = roots that originate from stem (or leaf tissue) rather than from the true root. All roots on monocots are adventitious. (e.g., corn and other grasses). http://plant-disease.ippc.orst.edu/plant_images/StrawberryRootLesion.JPG Root variation http://bio1903.nicerweb.com/Locked/media/ch35/35_04RootDiversity.jpg Flower variation http://130.54.82.4/members/Okuyama/yudai_e.htm Reproductive morphology: flower Yuan Yaowu Flower parts pedicel receptacle sepals petals Yuan Yaowu Flower parts Pedicel = (Latin: ped “foot”) stalk of a flower. -

Vegetative Vs. Reproductive Morphology

Today’s lecture: plant morphology Vegetative vs. reproductive morphology Vegetative morphology Growth, development, photosynthesis, support Not involved in sexual reproduction Reproductive morphology Sexual reproduction Vegetative morphology: seeds Seed = a dormant young plant in which development is arrested. Cotyledon (seed leaf) = leaf developed at the first node of the embryonic stem; present in the seed prior to germination. Vegetative morphology: roots Water and mineral uptake radicle primary roots stem secondary roots taproot fibrous roots adventitious roots Vegetative morphology: roots Modified roots Symbiosis/parasitism Food storage stem secondary roots Increase nutrient Allow dormancy adventitious roots availability Facilitate vegetative spread Vegetative morphology: stems plumule primary shoot Support, vertical elongation apical bud node internode leaf lateral (axillary) bud lateral shoot stipule Vegetative morphology: stems Vascular tissue = specialized cells transporting water and nutrients Secondary growth = vascular cell division, resulting in increased girth Vegetative morphology: stems Secondary growth = vascular cell division, resulting in increased girth Vegetative morphology: stems Modified stems Asexual (vegetative) reproduction Stolon: above ground Rhizome: below ground Stems elongating laterally, producing adventitious roots and lateral shoots Vegetative morphology: stems Modified stems Food storage Bulb: leaves are storage organs Corm: stem is storage organ Stems not elongating, packed with carbohydrates Vegetative -

Manual of Leaf Architecture

Manual of Leaf Architecture Morphological description and categorization of dicotyledonous and net-veined monocotyledonous angiosperms - 1 - ©1999 by Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Published and distributed by: Leaf Architecture Working Group c/o Scott Wing Department of Paleobiology Smithsonian Institution 10th St. & Constitution Ave., N.W. Washington, DC 20560-0121 ISBN 0-9677554-0-9 Please cite as: Manual of Leaf Architecture - morphological description and categorization of dicotyledonous and net-veined monocotyledonous angiosperms by Leaf Architecture Working Group. 65p. Paper copies of this manual were printed privately in Washington, D.C. We gratefully acknowledge funding from Michael Sternberg and Jan Hartford for the printing of this manual. - 2 - Names and addresses of the Leaf Architecture Working Group in alphabetical order: Amanda Ash Beth Ellis Department of Paleobiology 1276 Cavan St. Smithsonian Institution NHB Boulder, CO 80303 10th St. & Constitution Ave, N.W. Telephone: 303 666-9534 Washington, DC 20560-0121 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 202 357-4030 Fax: 202 786-2832 Email: [email protected] Leo J. Hickey Kirk Johnson Division of Paleobotany Department of Earth and Space Sciences Peabody Museum of Natural History Denver Museum of Natural History Yale University 2001 Colorado Boulevard 170 Whitney Avenue, P.O. Box 208118 Denver, CO 80205-5798 New Haven, CT 06520-8118 Telephone: 303 370-6448 Telephone: 203 432-5006 Fax: 303 331-6492 Fax: 203 432-3134 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Peter Wilf Scott Wing University of Michigan Department of Paleobiology Museum of Paleontology Smithsonian Institution NHB 1109 Geddes Road 10th St. & Constitution Ave, N.W. -

TREES of OHIO Field Guide DIVISION of WILDLIFE This Booklet Is Produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife As a Free Publication

TREES OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized reproduction is pro- hibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the ODNR Division of Wildlife and its contributing artists and photographers. For additional INTRODUCTION information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543). Forests in Ohio are diverse, with 99 different tree spe- cies documented. This field guide covers 69 of the species you are most likely to encounter across the HOW TO USE THIS BOOKLET state. We hope that this guide will help you appre- ciate this incredible part of Ohio’s natural resources. Family name Common name Scientific name Trees are a magnificent living resource. They provide DECIDUOUS FAMILY BEECH shade, beauty, clean air and water, good soil, as well MERICAN BEECH A Fagus grandifolia as shelter and food for wildlife. They also provide us with products we use every day, from firewood, lum- ber, and paper, to food items such as walnuts and maple syrup. The forest products industry generates $26.3 billion in economic activity in Ohio; however, trees contribute to much more than our economic well-being. Known for its spreading canopy and distinctive smooth LEAF: Alternate and simple with coarse serrations on FRUIT OR SEED: Fruits are composed of an outer prickly bark, American beech is a slow-growing tree found their slightly undulating margins, 2-4 inches long. Fall husk that splits open in late summer and early autumn throughout the state. -

Common Signs and Symptoms of Unhealthy Plants

® EXTENSION Know how. Know now. EC1270 Common Signs and Symptoms of Unhealthy Plants Amy D. Timmerman, Associate Extension Educator James A. Kalisch, Entomology Extension Associate Kevin A. Korus, Assistant Extension Educator Stephen M. Vantassel, Wildlife Program Coordinator Ivy Orellana, Extension Assistant Extension is a Division of the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln cooperating with the Counties and the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension educational programs abide with the nondiscrimination policies of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the United States Department of Agriculture. © 2014, The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska on behalf of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension. All rights reserved. Common Signs and Symptoms of Unhealthy Plants Amy D. Timmerman, Associate Extension Educator James A. Kalisch, Entomology Extension Associate Kevin A. Korus, Assistant Extension Educator Stephen M. Vantassel, Wildlife Program Coordinator Ivy Orellana, Extension Assistant Plant symptoms may be caused Along with the type of a plant part may be a sign of a by biotic (living organisms) or symptoms being expressed by the saprophyte (a nonparasitic fungus abiotic (nonliving) agents. Many plant, it can be important to observe growing on nutrients and organic abiotic factors can cause symptoms the colors that are associated with matter on the plant surface) and thus in a landscape or garden. These those symptoms. When making a might not be related to the actual factors include nutrient imbalances, diagnosis, description of color can be cause of disease. drought or excess soil moisture, a useful tool, such as the yellowing limited light, reduced oxygen of leaves associated with chlorosis.