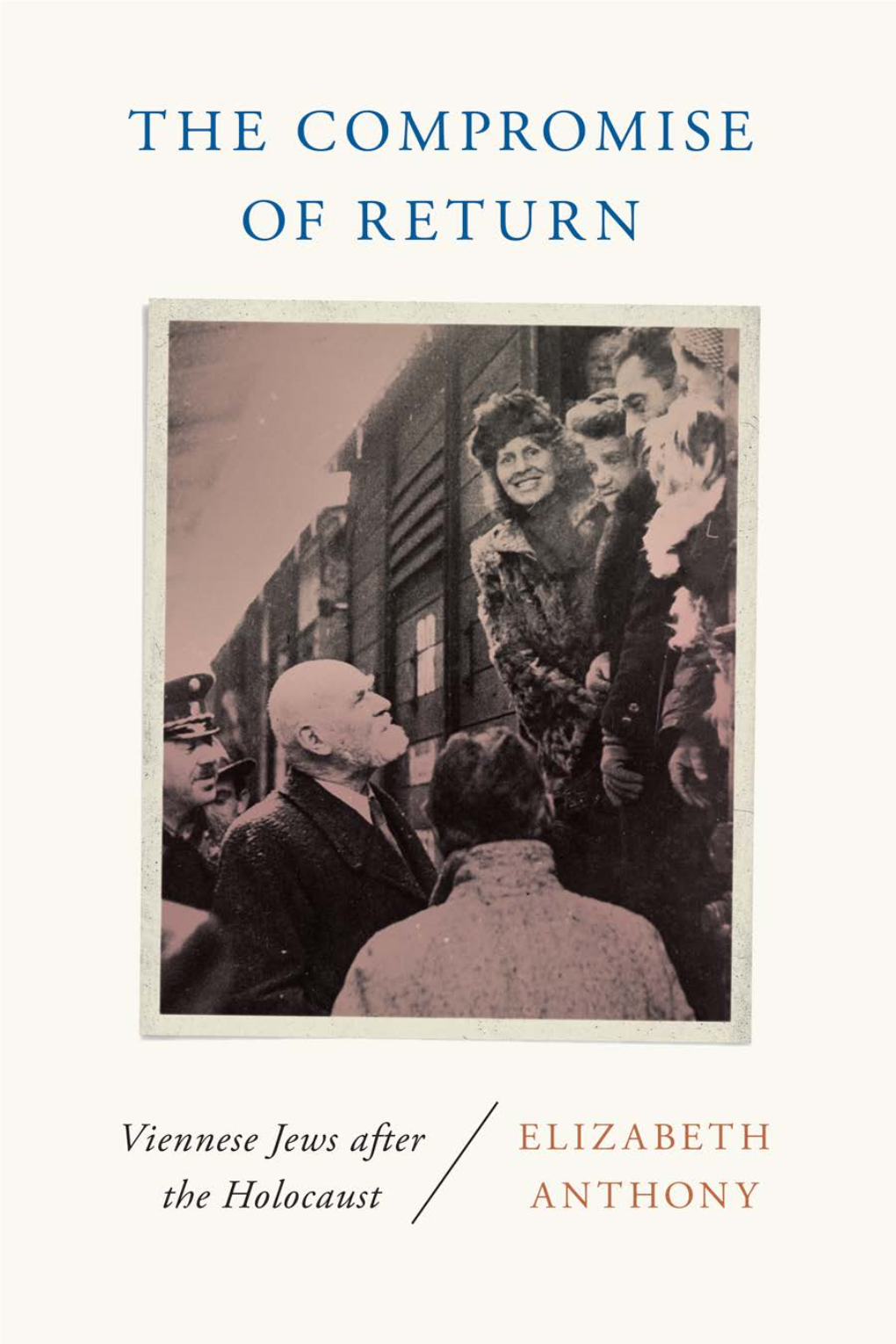

The Compromise of Return: Viennese Jews After the Holocaust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Vienna

Learn German Experience & Vienna YEAR- ROUND GERMAN COURSES for adults 16+ in Vienna and online SUMMER COURSES for young people 12-17 and 16-19 years in Vienna and online 2021/2022 www.actilingua.com » Languages are » I was surprised at how extremely important in safe a modern city can my job. German was my be! Even women can use weak point, and I man- the underground or walk aged to set this right in around alone late at night Vienna. It was a lot of fun without worries. « and therefore effortless. « Astrid Nielsen, Denmark Pablo Rodriguez, Spain ActiLingua at a glance One of the leading Courses for adults 16+ Content schools for German German courses in Vienna, Austria as well Learn German & Experience Vienna ...... 4 as live online courses. Courses for adults 16+ .................................... 5 as a foreign language. Maximum class-size: Course levels and certificates ..................... 8 12 (Standard Course), 8 (mini groups) International repu- Starting dates: every Monday, Accommodation .......................................... 10 tation, recommen- beginners once a month Activities ............................................................ 11 ded by major edu- German is taught year-round in small Summer School 12-17 years ...................... 12 international study groups. Holiday Course 16-19 years ..................... 13 cational consultants 20-30 lessons/week. Terms ................................................................. 14 worldwide. Certificate: Austrian German Language Diploma (ÖSD). Attractive pricing: Accommodation compare us with ActiLingua Residence, Host Family, language schools in Apartment, Student House; use of kitchen, breakfast or half-board. Germany! Transfer service on arrival/departure. Perfect nationality Activity and mix: students from leisure programme Included in course price: Vienna city more than 40 walks; talks on Austrian art, culture; countries. -

Licht Ins Dunkel“

O R F – J a h r e s b e r i c h t 2 0 1 3 Gemäß § 7 ORF-Gesetz März 2014 Inhalt INHALT 1. Einleitung ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Grundlagen........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Das Berichtsjahr 2013 ......................................................................................................... 8 2. Erfüllung des öffentlich-rechtlichen Kernauftrags.................................................................. 15 2.1 Radio ................................................................................................................................... 15 2.1.1 Österreich 1 ............................................................................................................................ 16 2.1.2 Hitradio Ö3 ............................................................................................................................. 21 2.1.3 FM4 ........................................................................................................................................ 24 2.1.4 ORF-Regionalradios allgemein ............................................................................................... 26 2.1.5 Radio Burgenland ................................................................................................................... 27 2.1.6 Radio Kärnten ........................................................................................................................ -

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection RG-50.862: EHRLICH COLLECTION - SUMMARY NOTES OF AUDIO FILES Introductory note by Anatol Steck, Project Director in the International Archival Programs Division of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: These summary transcription notes of the digitized interviews recorded by Leonard and Edith Ehrlich in the 1970s as part of their research for their manuscript about the Jewish community leadership in Vienna and Theresienstadt during the Holocaust titled "Choices under Duress" are a work in progress. The project started in April 2016 and is ongoing. The summary notes are being typed while listening to the recordings in real time; this requires simultaneous translation as many of the interviews are in German, often using Viennese vernacular and/or Yiddish terms (especially in the case of the lengthy interview with Benjamin Murmelstein which the Ehrlichs recorded with Mr. and Mrs. Murmelstein over several days in their apartment in Rome and which constitutes a major part of this collection). The summary notes are intended as a tool and a finding aid for the researcher; researchers are strongly encouraged to consult the digitized recordings for accuracy and authenticity and not to rely solely on the summary notes. As much as possible, persons mentioned by name in the interviews are identified and described in the text; however, as persons are often referred to in the interviews only by last name, their identification is sometimes based on the context in which their names appear within the interview (especially in cases where different persons share the same last name). -

Bundesregierung Gorbach 1 Von 2

Index IX. GP - Anhang - Bundesregierung Gorbach 1 von 2 7 Bundesregierung Gorbach vom 11. April 1961 bis 27. März 1963 Amtsdauer Bundesministerien Mitglieder der Bundesregierung und Staatssekretäre Ernannt am I Enthoben am **) Bundeskanzler Dr. Alfons Gorbach 27. März 1963 Bundes- 1110 April 1961 kanzleramt Vizekanzler Dr. Bruno **) Pittermann *) 27. März 1963 ) -- - ----- ------- **) Bundes- Bundesminister Dr. Bruno Kreisky 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 ministerium für Auswärtige Staatssekretär **) Angelegenheiten Dr. Ludwig Steiner 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 **) Bundesminister Josef Afritsch 11. April 1961 Bundes- 27. März 1963 ministerium für Inneres Staatssekretär Dr: Otto **) Kranzlmayr 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 . ~~~--~-----_._- Bundes- **) ministerium für Bundesminister Dr. Christian Broda 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 Justiz -- ---- Bundes- Dr. Heinrich 11. April 1961 **) ministerium für Bundesminister 27. März 1963 Unterricht Drimmel Bundes- **) ministerium für Bundesminister Anton Proksch 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 soziale Verwaltung - ---- ---.--- --------- .- Bundes- **) ministerium für Bundesminister Dr. Josef Klaus 11. April 1961 27. März 1963 Finanzen ---- - -- ------ Bundes- **) ministerium für Bundesminister Dipl.-Ing. Eduard 11. April 1961 Land- und Forst- Hartmann 27. März 1963 wirtschaft ---- --- -~-- - -_. *) Mit Entschließung des Bundespräsidenten vom 11. April 1961, BGBl. Nr. 96, wurde Vizekanzler Dr. Pittermann mit der sachlichen Leitung bestimmter zum Wirkungsbereich des Bundeskanzleramtes gehören• der Angelegenheiten gemäß Art. 77 Abs. 3 B.-VG. betraut. **) Die Bundesregierung wurde auf Grund ihrer Demission nach der Nationalratswahl (18. 11. 1962) vom Bundespräsidenten am 20. 11. 1962 vom Amte enthoben; gleichzeitig wurden die Mitglieder der Bundes regierung mit der Fortführung der von ihnen bisher innegehabten Ämter und der bisherige Bundeskanzler mit dem Vorsitz in der einstweiligen Bundesregierung betraut sowie die biSherigen Staatssekretäre wiederernannt ("Wiener Zeitung" Nr. -

Programmheft (Pdf)

Die ersten Europäer Habsburger und andere Juden – eine Welt vor 1914 Begleitprogramm Die ersten Europäer Habsburger und andere Juden – eine Welt vor 1914 25. März – 5. Oktober 2014 Hundert Jahre nach dem Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs steckt Europa erneut in einer tiefen Krise. Das Jüdische Museum Hohenems blickt zurück auf die Lebenswelt der „Habsburger Juden“ und ihre Erfahrungen, ihre transnationalen Netzwerke und ihre Mobilität, ihre Hoffnungen auf eine europäische Einigung und ihre Illusionen über das Habsburger „Vielvölkerreich“. Die Ausstellung präsentiert kostbare Leihgaben aus Museen und Sammlungen in Europa und den USA. Sie erzählt von Kaufleuten und Lastenträgern, Erfin- dern und verkauften „Bräuten“, Künstlern und Salon- damen, Hausiererinnen und Gelehrten, Spionen und Patrioten. So entfaltet die Schau das Panorama eines untergegangenen Reiches, vom späten Mittelalter bis 1914. Am Ende existierten mehr als 400 jüdische Gemeinden auf dem Gebiet der Habsburger Doppel- monarchie, in denen sich die ganze Vielfalt des Reiches widerspiegelte. Lange Zeit war Hohenems freilich die einzige öffentlich anerkannte jüdische Gemeinde auf dem Gebiet des heutigen Österreich westlich des Burgenlandes, bevor das Staatsgrundgesetz 1867 Juden den Eintritt in die Gesellschaft eröffnen sollte – und der moderne Antisemitismus zur neuen Heilslehre Europas wurde. Juden gehörten in dieser Welt vor 1914 zu den aktivsten Mittlern zwischen den Kulturen und Regionen. Ihre Mobilität und ihre grenzüber- schreitenden Beziehungen machten sie zum dynami- schen Element der europäischen Entwicklung. Die Angehörigen dieser jüdischen Gemeinden waren alles andere als homogen. Sie bestanden aus Monar- chisten und Revolutionären, aus Chassidim und Maskilim, Frommen und Aufgeklärten, ländlichen und urbanen Juden, Armen und Reichen, Traditionalisten und Kämpfern für Gleichheit und Recht, Feministinnen und Utopisten. -

Crossing Central Europe

CROSSING CENTRAL EUROPE Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Crossing Central Europe Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Edited by HELGA MITTERBAUER and CARRIE SMITH-PREI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2017 Toronto Buffalo London www.utorontopress.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Crossing Central Europe : continuities and transformations, 1900 and 2000 / edited by Helga Mitterbauer and Carrie Smith-Prei. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 (hardcover) 1. Europe, Central – Civilization − 20th century. I. Mitterbauer, Helga, editor II. Smith-Prei, Carrie, 1975−, editor DAW1024.C76 2017 943.0009’049 C2017-902387-X CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Tor onto Press. The editors acknowledge the financial assistance of the Faculty of Arts, University of Alberta; the Wirth Institute for Austrian and Central European Studies, University of Alberta; and Philixte, Centre de recherche de la Faculté de Lettres, Traduction et Communication, Université Libre de Bruxelles. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the -

Step 2025 Urban Development Plan Vienna

STEP 2025 URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VIENNA TRUE URBAN SPIRIT FOREWORD STEP 2025 Cities mean change, a constant willingness to face new develop- ments and to be open to innovative solutions. Yet urban planning also means to assume responsibility for coming generations, for the city of the future. At the moment, Vienna is one of the most rapidly growing metropolises in the German-speaking region, and we view this trend as an opportunity. More inhabitants in a city not only entail new challenges, but also greater creativity, more ideas, heightened development potentials. This enhances the importance of Vienna and its region in Central Europe and thus contributes to safeguarding the future of our city. In this context, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 is an instrument that offers timely answers to the questions of our present. The document does not contain concrete indications of what projects will be built, and where, but offers up a vision of a future Vienna. Seen against the background of the city’s commit- ment to participatory urban development and urban planning, STEP 2025 has been formulated in a broad-based and intensive process of dialogue with politicians and administrators, scientists and business circles, citizens and interest groups. The objective is a city where people live because they enjoy it – not because they have to. In the spirit of Smart City Wien, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 suggests foresighted, intelli- gent solutions for the future-oriented further development of our city. Michael Häupl Mayor Maria Vassilakou Deputy Mayor and Executive City Councillor for Urban Planning, Traffic &Transport, Climate Protection, Energy and Public Participation FOREWORD STEP 2025 In order to allow for high-quality urban development and to con- solidate Vienna’s position in the regional and international context, it is essential to formulate clearcut planning goals and to regu- larly evaluate the guidelines and strategies of the city. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Vienna Guide

April 22—24, 2015, Vienna, Austria Hotel Park Royal Palace Vienna Guide SIGHTSEEING Vienna is old, Vienna is new… and the sights are so varied: from the magnificent Baroque buildings to “golden” Art Nouveau to the latest architecture. And over 100 museums beckon… ALBERTINA The Albertina has the largest and most valuable graphical collection in the world, including works such as Dürer’s “Hare” and Klimt‘s studies of women. Its latest exhibition presents masterpieces of the Modern era, spanning from Monet to Picasso and Baselitz. As the largest Hapsburg residential palace, the Albertina dominates the southern tip of the Imperial Palace on one of the last remaining fortress walls in Vienna. ANKER CLOCK This clock (built 1911–14) was created by the painter and sculptor Franz von Matsch and is a typical Art Nouveau design. It forms a bridge between the two parts of the Anker Insurance Company building. In the course of 12 hours, 12 historical figures (or pairs of figures) move across the bridge. Every day at noon, the figures parade, each accompanied by music from its era. AUGARTEN PORCELAIN MANUFacTORY Founded in 1718, the Vienna Porcelain Manufactory is the second-oldest in Europe. Now as then, porcelain continues to be made and painted by hand. Each piece is thus unique. A tour of the manufactory in the former imperial pleasure palace at Augarten gives visitors an idea of how much love for detail goes into the making of each individual piece. The designs of Augarten have been created in cooperation with notable artists since the manufactory was established.