Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Other Books by Michio Kaku

Other books by Michio Kaku PARALLEL WORLDS EINSTEIN'S COSMOS VISIONS HYPERSPACE BEYOND EINSTEIN A SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION INTO THE WORLD OF PHASERS, FORCE FIELDS, TELEPORTATION, AND TIME TRAVEL Doubleday NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY AUCKLAND PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY Copyright © 2008 by Michio Kaku All Rights Reserved Published in the United States by Doubleday, an imprint of The Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.doubleday.com DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaku, Michio. Physics of the impossible : a scientific exploration into the world of phasers, force fields, teleportation, and time travel / Michio Kaku. -1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Physics-Miscellanea. 2. Science-Miscellanea. 3. Mathematical physics- Miscellanea. 4. Physics in literature. 5. Human-machine systems. I. Title. QC75.K18 2008 530-dc25 2007030290 ISBN 978-0-385-52069-0 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 13579 10 8642 First Edition To my loving wife, Shizue, and to Michelle and Alyson CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xix Part I: Class I Impossibilities 1: Force Fields 3 2: Invisibility 16 3: Phasers and Death Stars 34 4: Teleportation 53 5: Telepathy 70 6: Psychokinesis 88 7: Robots 103 8: Extraterrestrials and UFOs 126 9: Starships 154 10: Antimatter and Anti-universes 179 Part II: Class II Impossibilities 11: Faster Than Light 197 12: Time Travel 216 13: Parallel Universes 229 Part III: Class III Impossibilities 14: Perpetual Motion Machines 257 15: Precognition 272 Epilogue: The Future of the Impossible 284 Notes 305 Bibliography 317 Index 319 If at first an idea does not sound absurd, then there is no hope for it. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

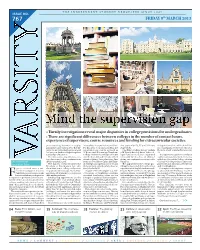

Varsity Issue

THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1947 ISSUE NO. th 767 FRIDAY 8 MARCH 2013 EV1122, DAVIDSIMMONS, TULANE PUBLIC RELATIONS TULANE PUBLIC EV1122, DAVIDSIMMONS, ZABETHEASTCOBBER, TYTUP, LENSCAPBOB, TRINITY.CAM.AC.UK, INKL TRINITY.CAM.AC.UK, LENSCAPBOB, TYTUP, ZABETHEASTCOBBER, MindO CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM ind the supervisionsuper gap PHOTO CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: 303STAINLESSSTEEL, ELI 303STAINLESSSTEEL, LEFT: TOP CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM PHOTO • Varsity investigations reveal major disparities in college provisions for undergraduates • There are significant differences between colleges in the number of contact hours, experience of supervisors, course resources and funding for extracurricular societies peers studying elsewhere - despite inequalities in supervision provision. rst years with 53, 55 and 59 hours of supervision time, while their Trin- paying the same tuition fees. e dif- For rst year economics students the respectively. ity counterparts received 43. ose at ferences are particularly pronounced supervision gap can be as much as One King’s College history student Homerton had 38 and at Roinson only for rst year students beginning their 71 hours, with the average Newnham told Varsity that they knew “other col- 33. Cambridge educations. College student receiving 115 hours leges have more classes organised e supervision gap for second year e data covers supervisions, col- over the year, but only 43 hours if they internally by directors of studies”, mathematicians was up to 33 hours, lege classes and college seminars from attended Sidney Sussex last year. First giving one explanation for the wide with Lucy Cavendish College o ering byPHELIM BRADY the last academic year. years at Gonville & Caius and Trin- variation. 62 hours of college contact time com- Deputy News Editor The figures, released under the ity College saw supervisors for 89 and e gap between the college pro- pared with just 28 hours at Homerton Freedom of Information Act, also 66 hours respectively, while those at viding the most and the least hours of and 30 at Magdalene. -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros. -

Kansas – Point of Know Return Live

Kansas – Point Of Know Return Live & Beyond (43:41 + 68:31, CD, Digital, Vinyl, InsideOut Music / Sony Music, 2021) Nach diversen Umbesetzungen vor einigen Jahren ist das amerikanische Progschlachtschiff Kansas wieder schwer auf Kurs. Man legte nach dem geglückten Neustart mit The„ Prelude Implicit“ (2016) und besonders „The Absence Of Presence“ (2020) nicht nur zwei prächtige Studioalben vor, auch live präsentiert sich die Band nach der alterstechnischen Blutauffrischung vitaler denn je. Deswegen geht ebenfalls „Live & Beyond“ in die zweite Runde. Vor rund drei Jahren würdigte man bereits den 76er Klassiker „Leftoverture“ in seiner Gesamtheit im Livekontext, jetzt folgt der zweite, ebenfalls verkaufstechnisch sehr erfolgreiche Platinum Seller „Point Of Know Return“. Wies das erste „Live & Beyond“ Package noch einige Makel auf, besonders durch die massive Verwendung von Autotune bei den Gesangspassagen, so macht die Band dieses Mal alles richtig. Gerade der Steve Walsh Nachfolger Ronnie Platt hat anscheinend wesentlich mehr an Vertrauen in seine eigene Stimmkraft gewonnen und liefert eine perfekte Performance voller vokaler Leidenschaft ab. Natürlich gibt es einige Überschneidungen mit dem letzten Livepackage, da man eben nicht grundsätzlich auf „Leftoverture“ Klassiker wie ‚The Wall‘, ‚Miracles Out Of Nowhere‘ und dem unverwüstlichen ‚Carry On Wayward Son‘ verzichten wollte. Doch neben dem kompletten 77er Album „Point Of Know Return“ bietet man einen sehr gut austarierten Mix aus Klassikern, neuem Material (u.a. ‚Summer‘ und ‚Refugee‘ von „The Prelude Implicit“), aber auch selten gehörtes Material wie das äußerst dynamisch interpretierte ‚Two Cents Worth‘ von „Masque“ (1975) oder die ursprünglich vonSteve Morse geprägten ‚Musicatto / Taking In The View‘ von „Power“ (1986). Was aber in erster Linie überzeugt, ist die Hingabe, Spielfreude und unglaubliche Power, die die aktuelle Kansas Besetzung auf der Bühne bietet. -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY -

New AV List for November 2020

NEW AV MATERIALS November 2020 CD Title Call # Author After hours CD Wee (Pop/Rock) Weeknd Agricultural tragic CD Lun (Country Music) Lund, Corb Alicia CD Key (Pop/Rock) Keys, Alicia Alive CD Eag (Country Music) Eaglesmith, Fred J. All rise CD Por (Jazz) Porter, Gregory All that emotion CD Geo (Pop/Rock) Georgas, Hannah American standard CD 389 Tay (Pop/Rock) Taylor, James Angel Miners & The CD Awo (Pop/Rock) AWOLNATION Lightning Riders Artemis CD Art (Jazz) Artemis B7 CD Bra (Pop/Rock) Brandy Bigger love CD Leg (Pop/Rock) Legend, John Blackbirds CD Lav (Blues) LaVette, Bettye Bless your heart CD All (Pop/Rock) Allman Betts Band Blessed songs of CD Bri (Christian/Gospel) Brickman, Jim inspiration Born here live here die CD Bry (Country Music) Luke, Bryan here Brightest blue CD Gou (Pop/Rock) Goulding, Ellie Calm CD Fiv (Pop/Rock) 5 Seconds of Summer Can we fall in love CD Ava (Pop/Rock) Avant Ceelo Green is Thomas CD Gre (Pop/Rock) Green, Ceelo Callaway Chromatica CD Lad (Pop/Rock) Lady Gaga Church house blues CD Sha (Blues) Shawanda, Crystal Circles CD Mil (Rap) Miller, Mac Crave CD Kie (Pop/Rock) Kiesza Dedicated side B CD Jep (Pop/Rock) Jepsen, Carly Rae Easy to buy, hard to sell CD Sle (Pop/Rock) Sleep Eazys Echoes CD Jer (Folk music) Jerry Cans Eleven words CD Fos (Instrumental) Foster, David Ella 100 live at The Apollo! CD Ell (Jazz) Various artists Everything means nothing CD Bla (Blues) Blackbear Fetch the bolt cutters CD App (Pop/Rock) Apple, Fiona First rose of spring CD Nel (Country Music) Nelson, Willie Folklore CD Swi (Pop/Rock)