Tchaikovsky Deserves Being Listed As on of the Greatest Contrapuntists Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

You Conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in Their Annual Ball at the Musikverein, the Day Before Yesterday

Interview with conductor Semyon Bychkov Tutti-magazine: You conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in their annual ball at the Musikverein, the day before yesterday. What did you take away from the experience ? Semyon Bychkov: It was an extraordinary experience, it is hard to find words to describe it. The women and the debutantes were dressed in sumptuous ball gowns and the atmosphere made it feel as if one were in the 19th century. For someone like me who sometimes wishes they’d lived in the 18th or 19th centuries, the evening reminded me of a style approrpriate to a particularly beautiful past. As I’ve said many times to your colleagues, I would be very happy if this beautiful and joyful spirit could be shared by as many people as possible and offer an alternative to the vulgarity and violence which occur daily in the world today. As I was leaving on tour with the Vienna Philharmonic, I arrived to drop my things off at the Great Hall of the Musikverein in the afternoon – the following day we would be playing in Hamburg at the Elbphilharmonie - the Hall was deserted and the view was so extraordinary that I couldn’t resist taking some photographs : all the stalls seats had been removed and replaced by flowers and tables. Of course I also noticed the wall covered with photographs of conductors who had worked with the orchestra, and thought: «So here is the conductors’ wall of fame»… That evening, immediately after our concert, everything that had been installed was moved to the large empty space under the floor of the Hall. -

Tchaikovsky Schumann

NI 6222 SYMPHONY NO.6 IN B MINOR Op.74 TCHAIKOVSKY PATHÉTIQUE Symphony no.6 Pathétique 1 Adagio, Allegro non troppo 20’26 2 Allegro con gracia 8’18 3 Allegro molto vivace 9’39 4 Finale: Adagio lamentoso 10’53 SCHUMANN Overture to Manfred 5 OVERTURE TO MANFRED Op.115 13’20 Total playing time: 62’36 2013 Wyastone Estate Ltd. Wyastone 2013 g London Symphony Orchestra Yondani Butt 2013 Wyastone Estate Ltd. Wyastone 2013 Produced by Chris Craker by Produced Haram Simon Rhodes, edited by Simon by Engineered 2012 London on 16th & 19th November, Studios, Road at Abbey Recorded P Yondani Butt ~ conductor In February 1893, after an intense but hugely successful tour in the Russian city of Odessa, Tchaikovsky embarked on the composition of his Sixth Symphony. He was in Yondani Butt was born in Macau. He studied music at Indiana University and the ebullient mood, having been treated as a celebrity in Odessa. Back in Klin, Tchaikovsky University of Michigan. He also has a Ph.D. in Chemistry, on which subject he has wrote to his brother Anatoly in mid February: ‘It seems that the best of all my works is published numerous research papers. As founder of Symphonie Canadiana, he has led the coming forth from me.’ There are many who would agree with this appraisal: the Sixth orchestra on major tours throughout North America. In addition, since 1983, he has held Symphony is one of Tchaikovsky’s greatest achievements, marrying a sweeping structure the position of Resident Conductor of the Victoria International Festival, creating the with exquisite emotional depth. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

A Tchaikovsky Spectacular: "1812" ・ Romeo and Juliet ・ Marche Slave Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tchaikovsky A Tchaikovsky Spectacular: "1812" ・ Romeo And Juliet ・ Marche Slave mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: A Tchaikovsky Spectacular: "1812" ・ Romeo And Juliet ・ Marche Slave Country: Netherlands Released: 1987 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1760 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1866 mb WMA version RAR size: 1721 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 216 Other Formats: AUD WAV MMF AAC DXD DTS XM Tracklist 1 Overture "1812" Op. 49 16:25 2 Marche Slave, Op. 31 9:34 3 Romeo And Juliet (Fantasy Overture) 20:34 Credits Art Direction – Marvin Schwartz Composed By – Tchaikovsky* Design – Marvin Schwartz Painting [Uncredited; "Battle Of Moscow, 7th September 1812"] – Louis-François Lejeune Photography By – Clive Barda Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 24347 95352 1 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year London Symphony London Symphony Orchestra* Conducted Orchestra* Angel S-36890 By André Previn - A S-36890 US 1973 Conducted By Records Tchaikovsky Spectacular André Previn (LP) Tchaikovsky*, André Tchaikovsky*, Previn, The London André Previn, The Symphony Orchestra - Hi-Q HIQLP007 HIQLP007 UK 2011 London Symphony 1812 Overture / Romeo Records Orchestra And Juliet / Marche Slave (LP) Orquesta Sinfónica De Londres* Dirigida Por Orquesta Sinfónica 1 J André Previn - 1 J De Londres* La Voz De 065-02.365 Tchaikovsky Obertura 065-02.365 Spain 1974 Dirigida Por André Su Amo Q "1812" Romeo Y Julieta - Q Previn Marcha Eslava (LP, Album, Quad, SQ ) London Symphony London Symphony Orchestra* Orchestra* Conducted His Q4ASD Q4ASD Conducted By By André Previn / Master's UK 1973 2894 2894 André Previn / Tchaikovsky* - 1812 Voice Tchaikovsky* Overture (LP, Quad) London Symphony London Symphony Orchestra* Conducted Orchestra* His TC ASD By André Previn / TC ASD Conducted By Master's UK 1973 2894 Tchaikovsky* - 1812 2894 André Previn / Voice Overture Etc. -

Tchaikovsky, Manfred Symphony

rg Pyotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY Manfred Symphony Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer. He had begun piano lessons at the age of 5, and beFore turning 8, his sight-reading eclipsed that oF his teacher. Despite his musical precociousness, Tchaikovsky's parents did not believe that a career as a musician was Feasible in Russia, and sent the 10-year-old Tchaikovsky to boarding school to be educated for a career in the government. This early separation From his mother — who would die From cholera when Tchaikovsky was 14 — would create a liFelong trauma. Despite this turmoil, Tchaikovsky graduated at 19 and became a senior assistant at the Ministry of Justice in St. Petersburg the same year. Concurrently, Anton Rubinstein had founded the Russian Musical Society (Russia's First music school open to the public) in St. Petersburg, and Tchaikovsky attended classes at the school (which became the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1862). As a prized student, Tchaikovsky was oFFered a job as a professor by Anton Rubinstein's brother, Nikolai, at what would soon become the Moscow Conservatory. In the following years, as his career grew, the public became increasingly interested in Tchaikovsky's private life. Contending with his homoseXuality — banned in Russia apart From the upper classes at the time — Tchaikovsky married a previous student of his, but ran away From her within 3 months. He had also Formed a relationship with Nadezhda von Meck in 1878, — the widow oF a railway magnate who greatly admired Tchaikovsky's work — who became his patroness, enabling him to devote all of his time to composition. -

RUSSIAN & UKRAINIAN Russian & Ukrainian Symphonies and Orchestral Works

RUSSIAN & UKRAINIAN Russian & Ukrainian Symphonies and Orchestral Works Occupying a vast land mass that has long been a melting pot of home-spun traditions and external influences, Russia’s history is deeply encrypted in the orchestral music to be found in this catalogue. Journeying from the Russian Empire through the Soviet era to the contemporary scene, the music of the Russian masters covers a huge canvas of richly coloured and immediately accessible works. Influences of folklore, orthodox liturgy, political brutality and human passion are all to be found in the listings. These range from 19th-century masterpieces penned by ‘The Mighty Five’ (Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Cui) to the edgy works of Prokofiev and Shostakovich that rubbed against the watchful eye of the Soviet authorities, culminating in the symphonic output of one of today’s most noted Russian composers, Alla Pavlova. Tchaikovsky wrote his orchestral works in a largely cosmopolitan style, leaving it to the band of brothers in The Mighty Five to fully shake off the Germanic influence that had long dominated their homeland’s musical scene. As part of this process, they imparted a thoroughly ethnic identity to their compositions. The titles of the works alone are enough to get the imaginative juices running, witness Borodin’s In the Steppes of Central Asia, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh, and Mussorgsky’s St John’s Night on the Bare Mountain. Supplementing the purely symphonic works, instrumental music from operas and ballets is also to be found in, for example, Prokofiev’sThe Love for Three Oranges Suite, Shostakovich’s four Ballet Suites, and Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite. -

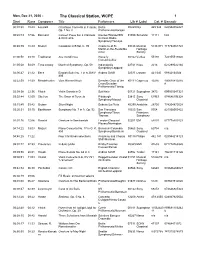

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Dec 21, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 19:43 Locatelli Christmas Concerto in F minor, Berlin X0229 DG 449 924 028944992427 Op. 1 No. 8 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:22:1317:26 Barmann Concert Piece For 2 Clarinets Klocker/Wandel/SW 01999 Schwann 11111 N/A & Orchestra German Radio Symphony/Tomayo 00:40:3918:49 Mozart Cassation in B flat, K. 99 Academy of St. 09186 Musical 513617H 717794361728 Martin-in-the-Fields/Ma Heritage rriner Society 01:00:58 03:10 Traditional Ave mundi rosa Waverly X0162 Veritas 55193 724355519320 Consort/Jaffee 01:05:0854:09 Tchaikovsky Manfred Symphony, Op. 58 Indianapolis 02781 Koss 2216 021299022160 Symphony/Leppard 02:00:47 21:12 Bach English Suite No. 1 in A, BWV Andras Schiff 02530 London 421 640 08942164024 806 02:22:5914:39 Mendelssohn Vom Himmel Hoch Dresden Choir of the X0111 Capriccio 10216 400640810216 Cross/Dresden 8 Philharmonic/Flamig 02:38:3822:36 Fibich Violin Sonata in D Suk/Hala 05721 Supraphon 3473 099925347321 03:02:44 12:05 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Pittsburgh 03810 Sony 61963 074646196328 Symphony/Maazel Classical 03:15:4903:42 Gruber Silent Night Dubeau/La Pieta X0290 Analekta 28730 774204873028 03:20:3139:15 Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92 San Francisco 10923 San 0054 821936005422 Symphony/Tilson Francisco Thomas Symphony 04:01:16 12:06 Rossini Overture to Semiramide London Classical 02201 EMI 54091 077775409123 Players/Norrington 04:14:2233:03 Mozart Piano Concerto No. 17 in G, K. -

The Impact of Russian Music in England 1893-1929

THE IMPACT OF RUSSIAN MUSIC IN ENGLAND 1893-1929 by GARETH JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham March 2005 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the reception of Russian music in England for the period 1893-1929 and the influence it had on English composers. Part I deals with the critical reception of Russian music in England in the cultural and political context of the period from the year of Tchaikovsky’s last successful visit to London in 1893 to the last season of Diaghilev’s Ballet russes in 1929. The broad theme examines how Russian music presented a challenge to the accepted aesthetic norms of the day and how this, combined with the contextual perceptions of Russia and Russian people, problematized the reception of Russian music, the result of which still informs some of our attitudes towards Russian composers today. Part II examines the influence that Russian music had on British composers of the period, specifically Stanford, Bantock, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Frank Bridge, Bax, Bliss and Walton. -

Beloved Friend: Tchaikovsky Project with Semyon Bychkov

Recording Press Quotes Czech Philharmonic Beloved Friend: Tchaikovsky Project with Semyon Bychkov Boxset Release 30 August 2019 (Decca Classics) Inaugural Trophée Radio Classique Nomination 2019 A delectable package for the Tchaikovsky lover: most of the composer's great orchestral concert music, performed by Russian conductor Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic. They give us the six numbered symphonies plus Manfred, Romeo and Juliet, the Serenade for Strings and the three Piano Concertos with Kirill Gerstein as soloist. It is especially rewarding to have the original versions of the First and Second Concertos. Beautifully played, charismatically interpreted. The Daily Mail, 27 December 2019 6 of the Best in 2019 Each of the other six symphonies, in its own way, receives revelatory treatment, helped by the exceptional quality of the Decca recorded sound... Although the orchestral writing of the first three is sublime, they lack the show-stopping tunes of the later ones, and the great ensemble passages of Manfred. Thanks to the clarity, in every sense, of these performances, one can make a fresh assessment of the first three, for their depths become immediately apparent. As for the “big three”: the Fifth is perhaps the most brilliant and assured performance, showing Tchaikovsky in all his moods... the Sixth teeters on perfection. If you are still wondering what to ask for from Father Christmas, you could do far worse than this stunning collection. The Daily Telegraph, 23 December 2019 The Tchaikovsky cycle is a well though-through project in which every detail has been considered with exquisite care, from the interpretation to the capturing of the sound. -

Manfred Symphony

PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY MANFRED SYMPHONY Sit back and enjoy Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky The redemption of himself to this and to its eponymous The Manfred Symphony: an experienced before his death at only Manfred Symphony, Op. 58 hero with zeal, and seemed to unrestrained self-portrait 36 years of age, was enough to cover Manfred even somewhat transform himself Romantic poet surrounded by several lifetimes: inheriting a title 1. Lento lugubre – Moderato con moto – Andante 17.27 into Manfred during the intensive scandal and strife-torn hero – the at 10 years old, entering the House 2. Vivace con spirito 9.57 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Manfred is period of work. After all, he was literary model of Lords when he came of age; 3. Andante con moto 11.24 a hermaphrodite – at least, as far as also suffering from inner torment. Had George Gordon Noel Byron early travels to the Mediterranean 4. Allegro con fuoco 20.21 the music is concerned. For although And this can be heard in the music, lived in the present day, then the and further onwards to Asia Minor; the work (dating from 1885) was which appears to be full of inner abundant major and minor scandals instantaneous literary fame thanks 59.29 indeed dubbed by its creator as a conflict. Nowadays, Manfred that surrounded him would almost to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage; social symphony, it still did not receive is rarely heard in the concert certainly have given the ever-hungry scandals following relationships a number alongside Tchaikovsky’s hall. Perhaps due to its rather tabloid press something to feast on.