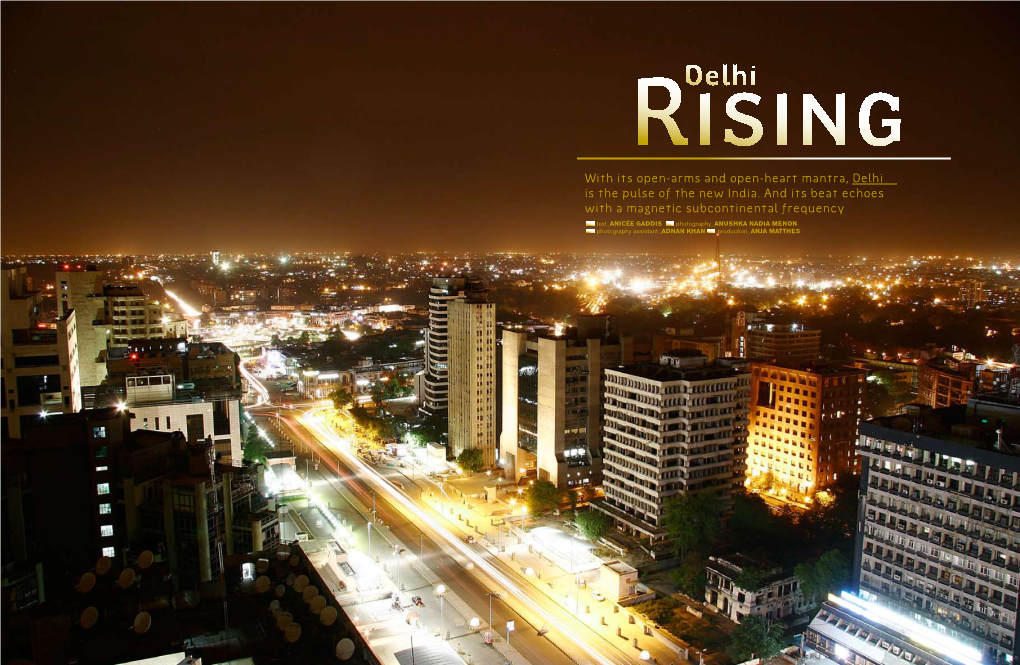

With Its Open-Arms and Open-Heart Mantra, Delhi Is the Pulse of the New India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215 the History and Practice of Naming Streets in Delhi

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May 2017; Page No. 215-218 The history and practice of naming streets in Delhi Nidhi M.A (F), Delhi School of Economics, Delhi, India Introduction: History of Streets which naming streets took place have changed considerably. The word ‘Street’ was borrowed from Latin language. The Delhi, India’s capital is believed to be one of the oldest cities Roman strata or paved roads were taken up to drive the word of the world. From Indraprastha to New Delhi, it had been a street. The word street helps us to recognise the roman roads long journey. As popularly believed, Delhi has been the site which were straight as an arrow, connecting the strategic for seven historic cities- Lalkot, Siri, Tughlaqabad, Jahan positions in the region. Panah, Ferozabad, Purana Quila and Shahajahanabad. The early forms of street transport were horses or even Shahajahanabad remains a living city till present housing humans carrying goods over tracks. The first improved trails about half a million people. would have been at mountain passes and through swamps. As 2.5.1 Street names of Shahajahanabad: Mughal Capital trade increased, the tracks were often flattened or widened to The seventh city of Delhi, Shahajahanabad was built in 1638 accommodate human and animal traffic, Some of these soil on the banks of river Yamuna. The two major streets of tracks were developed into broad networks, allowing Shahajahanabad were Chandni Chowk and Faiz Bazaar. -

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00Pm This Is the 939Th Concert in Koerner Hall

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00pm This is the 939th concert in Koerner Hall Anoushka Shankar, sitar Ojas Adhiya, tabla Pirashanna Thevarajah, mridangam Ravichandra Kulur, flute Danny Keane, cello & piano Kenji Ota, tanpura Anoushka Shankar Sitar player and composer Anoushka Shankar is a singular figure in the Indian classical and progressive world music scenes. Her dynamic and spiritual musicality has garnered several prestigious accolades, including six Grammy Award nominations, recognition as the youngest – and first female – recipient of a British House of Commons Shield, credit as an Asian Hero by TIME magazine, an Eastern Eye Award for Music, and a Songlines Best Artist Award. Most recently, she became one of the first five female composers to have been added to the UK A-level music syllabus. Deeply rooted in the Indian classical music tradition, Shankar studied exclusively from the age of nine under her father and guru, the late Ravi Shankar, and made her professional debut as a classical sitarist at the age of 13. By the age of 20, she had made three classical recordings for EMI/Angel and received her first Grammy nomination, thereby becoming the first Indian female and youngest-ever nominee in the world music category. She is also the first Indian artist to perform at the Grammy Awards. In addition to performing as a solo sitarist, her compositional work has led to cross-cultural collaborations with artists such as Sting, M.I.A., Herbie Hancock, Pepe Habichuela, Karsh Kale, Rodrigo y Gabriela, and Joshua Bell, demonstrating the versatility of the sitar across musical genres. -

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981, in London, and is the daughter of the famous sitar player Ravi Shankar. She was brought up in London, Delhi and California, where she attended high school. She studied sitar with her father from the age of 7, began playing tampura in his concerts at 10, and gave her first solo sitar performances at 13. She signed her first recording contract at 16 and her first three album releases were of Indian Classical performances. Her first cross-over/fusion album – Rise – was released in 2005 and was nominated for a Grammy, in the Contemporary World Music category. Her albums since Breathing Under Water have continued to explore the connections between Indian music and other styles. She has collaborated with some major artists – Sting, Nithin Sawhney, Joshua Bell and George Harrison, as well as with her father, Ravi Shankar, and her half-sister, Norah Jones. She has also performed around the world as a Classical sitar player – playing her father’s sitar concertos with major orchestras. The piece Breathing Under Water was Anoushka Shankar’s fifth album, and her second of original fusion music. Her main collaborator was Utkarsha (Karsh) Kale, an Indian musician and composer and co-founder of Tabla Beat Science – an Indian band exploring ambient, drum & bass and electronica in a Hindustani music setting. Kale contributes dance music textures and technical expertise, as well as playing tabla, drums and guitar on the album. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

1 DELHI TRAFFIC POLICE TRAFFIC ADVISORY Traffic Arrangements

DELHI TRAFFIC POLICE TRAFFIC ADVISORY Traffic Arrangements – Republic Day Celebrations on 26Th January, 2021 Republic Day will be held on 26th January, 2021. The Parade will start at 9.50 AM from Vijay Chowk and proceed to National Stadium, whereas Tableaux will start from Vijay Chowk and proceed to Red Fort Ground . There will be wreath laying function at National War Memorial at 09.00 AM. There would be elaborate traffic arrangements and restrictions in place for smooth conduct of the Parade and Tableaux along the respective routes. ROUTE OF THE PARADE/TABLEAUX :- (A) Parade Route:- Vijay Chowk- Rajpath- Amar Jawan Jyoti- India Gate- R/A Princess Palace-T/L Tilak Marg Radial Road- Turn right on “C” Hexagon- Turn left and enter National Stadium from Gate No. 1. (B) Tableaux Route :- Vijay Chowk- Rajpath- Amar Jawan Jyoti- India Gate- R/A Princess Palace-T/L Tilak Marg - Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg – Netaji Subhash Marg - Red Fort. TRAFFIC RESTRICTIONS In order to facilitate smooth passage of the Parade, movement of traffic on certain roads leading to the route of the Parade and Tableaux will be restricted as under:- (1). No traffic will be allowed on Vijay Chowk from 06.00 PM on 25.01.2021 till Parade is over. Rajpath is already out of bounds. (2). No cross traffic on Rajpath intersections from 11.00 PM on 25.01.2021 at Rafi Marg, Janpath, Man Singh Road till Parade is over. (3). ‘C’-Hexagon-India Gate will be closed for traffic from 05.00 AM on 26.01.2021 till Tableaux crosses Tilak Marg. -

Photo Tour of Golden Triangle with Pushkare Fair in 2018

PHOTO TOUR OF GOLDEN TRIANGLE WITH PUSHKARE FAIR IN 2018 11 Nov 2018 Arrival Delhi Traditional welcome on arrival and transfer to hotel for overnight stay. (Only one arrival transfer is included in our tour package, supplement cost of USD 20 will be applicable if any guest will arrive in different flight) Note – Please note that check in time of hotel is 12 Noon 12 Nov 2018 Delhi After breakfast first photo opportunity at Humayun Tomb. Humayun's tomb is the tomb of the Mughal Emperor Humayun in Delhi, India. The tomb was commissioned by Humayun's first wife Bega Begum in 1569-70, and designed by Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, a Persian architect chosen by Bega Begum Later we will take you to the Qutab Minar which is the tallest brick minarety in the world, and the second tallest minar in India after Fateh Burj at Mohali. Qutub Minar, along with the ancient and medieval monuments surrounding it, form the Qutb Complex, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Made of red sandstone and marble, Qutub Minar is a 73-meter (240 feet) tall tapering tower with a diameter measuring 14.32 meters (47 feet) at the base and 2.75 meters (9 feet) at the peak. Inside the tower, a circular staircase with 379 steps leads to the top Afternoon (After Lunch) we will take you to the photo tour of Old Delhi. In the 17th century, the Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, made his capital in the area that broadly covers present-day Old Delhi—he called it Shahjahanabad. -

MIDIVAL PUNDITZ Hello Hello

MIDIVAL PUNDITZ Hello Hello This past decade has been marked by the rise of the Indian electronica scene and no single band has had more influence on its growth than the Midival Punditz. Comprised of New Delhi based producers Gaurav Raina and Tapan Raj, the Punditz have been repeatedly heralded as pioneers of a scene that has ushered in some of the freshest global music out of India. On their third studio album Hello Hello, the duo has successfully documented their own personal journey as artists and brought their sound into the present. As India’s influence on the world through music, film and fashion hits a new peak as evidenced by the worldwide popularity of the film Slumdog Millionaire, the Punditz have kept their hands on the wheel and helped steer this ship into a new century of sound and culture. Hello Hello encompasses all the varied worlds in which this producer/DJ team exists – tying them together through a sound that brings International Electronica, Global Pop, Folk, and Indian Classical with modern day song writing. The result is a sound that is uniquely Midival Punditz. For this album, the duo get support from longtime friend and collaborator Karsh Kale, working as co-producer, vocalist, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter. The album’s opener, “Electric Universe,” follows in the old tradition of “tonight’s-the-night” style dance hits. The majestic bansuri flute sets up the vocoder lyrics – “this is the night/to turn on the lights/to the universe” – over a sturdy, western dance groove. But at the end of the record, an acoustic version of the same song, with “real” vocals and acoustic guitar by Karsh Kale, turns it into a nocturne – as if to prove that despite all the bells and whistles, in the end it’s all about the song. -

Street the Heat

Food & Drink FINAL.qxd 7/16/2009 5:20 PM Page 36 Shahjahanabad coolers Street the heat Feeling a bit parched in purani Dilli, Sonal Shahquenches her thirst at various local institutions. Photography Taveeshi Singh Murarilal Inderjit Sharma Bikaner Sweet Shop The crowd outside Murari’s Compared to some surround- lassi, dahi, milk and paneer outlet ing vendors, this namkeen in Kinari Bazaar is relentless. shop is a newbie, having been Established about 60 years ago, established only 27 years ago. the dairy stall uses two of Delhi’s That certainly doesn’t stop Food & Drink classic “Sultan” machines to passers-by from availing of the churn creamy – but not excessive- shop’s convenient location in ly thick – lassi in kullars and steel Dariba, just out of the sun of glasses. Some of the area’s mer- Chandni Chowk. A bucket of chants bring their own silver cups ice holds bottles of kaju milk, to be filled. A squirt of kewra is pista milk and badam milk. added and the glass is topped with 255 Dariba Kalan, off Chandni a thin, creamy-crisp slab of malai Chowk (2328-1971). before serving. A namkeen ver- m Chandni Chowk. Rs 20. sion is also available. 2178 Kinari Bazaar (2327-1464). m Chandni Chowk. Rs 20. Sheher-e-sharbat Though the line of sharbats is manu- factured in the dusty industrial Amritsari Lassi Wala area of Lawrence Road and despite The thickest lassi we’ve found in the fact that most of the ingredients old Delhi is available at this well- listed involve preservatives, known neon-yellow shop. -

Impact of Different Food Cultures on Cuisine of Delhi

International Journal of Research and Review www.ijrrjournal.com E-ISSN: 2349-9788; P-ISSN: 2454-2237 Review Paper Impact of Different Food Cultures on Cuisine of Delhi Chef Prem Ram1, Dr. Sonia Sharma2 1Asst. Professor BCIHMCT, New Delhi 2 School of Tourism and Hospitality Service Management (SOTHSM), IGNOU, New Delhi Corresponding Author: Chef Prem Ram ABSTRACT Culture of society and nation plays crucial role that is reflected and practiced in food industry in the big umbrella of food culture. Food culture talks about tradition, taboos, beliefs, rituals, interiors and influence of globalization being followed by the service provider that is being apparent in quality, quantity, varieties, taste, neatness and behaviour of service staffs as these factors lead to customer satisfaction for paid prices. The way that Food is produced, distributed, selected, obtained, afforded, stored, prepared, ordered, served, consumed, promoted, and learnt about can reveal much about the customs and attitudes of every social group (Counihan, 1998). This study is focused on Delhi only where food culture is a mixture of its past, different cultures and traditions. According to Gandhi (2015) the city of Delhi is a hub of cuisine. The city has absorbed, over the centuries, settlers, and visitors from across the globe. The emperors, the nobles, the viceroys and the sahibs all provided generous patronage to the cuisine of Delhi and contributed the cultivation of fine taste. Food culture is to be followed by concerned services provider and present study is an attempt to explore of food culture, cuisines, preferences and choices in Delhi through literature review. Key Words: Food Culture, cuisines, food preferences, food choices, and Hospitality. -

Tourism ABSTRACT Heritage Walk Area Interpretation and Experiences

Research Paper Volume : 2 | Issue : 7 | July Tourism 2013 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Heritage Walk Area Interpretation and KEYWORDS : Heritage, Walk, Experiences Interpretation, Experiences, Circuits etc. Dr. Arvind Kumar Assistant Professor and Programme Coordinator – BTS, BHM, MHA, EMBAHM, Dubey MIHM, NCHMCT programmes & MCC. ABSTRACT Delhi as one of the ancient cities, with its multiple layers of built heritage and living tradition offers a unique heritage walks experience to tourists. In order to experience and visualize these multiple layers of heritage and culture, tourists and locals are taking up heritage walks of some areas which offer a kaleidoscope of deep interest and significance such as Old Delhi , Mehrauli, Hauz Khas, Hazrat Nizamuddin, Lodhi Garden and Imperial Delhi. The present study has employed extensive field survey and literature review to obtain an understanding of why people undertake heritage walks, tourist expectations and their experiences on heritage walks. Introduction: Delhi, Delhi ridge, Hauzkhas, Hazrat Nizamuddin, Mehrauli, Lo- It is a well understood fact that conducting heritage walk is an dhi Garden and New Delhi (Imperial Delhi). These locations are art. Most of the tourists who are visiting any historical /cultural well marketed and appreciated in heritage walk circles. But it is site/ city are very much interested in understanding cultural interesting to note that certain valuable resources for conduct- and historical resources through heritage walk. But heritage ing heritage walks not yet developed and marketed are areas walk requires unique attributes such as stamina, curiosity, an such as Old Fort, Kotla Feroz Shah, Roshanara Bagh to Pir Ghaib eye for nature, inclination to listen and understand, endur- and Jahanpanah (Bijay Mandal to Begumpuri Masjid). -

The Perfume That Harnesses the Monsoon

The perfume that harnesses the monsoon Years ago, an Indian acquaintance told me of a particularly special perfume, one that is a distillation of the first rains of the monsoon. Iʼd long wanted to find it – but with the modern proliferation of synthetic-based scents, traditional attars, or oil-based perfumes, are increasingly hard to source. Gulab Singh Johrimal in Old Delhi, I was told, is likely to have it. Gulab Singh Johrimal has been dispensing attars for more than 200 years. Soon after rolling up the shutters in the morning, the perfumery attracts a steady stream of visitors of all stripes, from well-dressed women with cut- glass accents to teenage suitors buying a scent for their paramour. All know Gulab Singh Johrimal as the house of sublime scents. Gulab Singh Johrimal has been selling attars in Old Delhi for more than 200 years (Credit: Peter Lopeman/Alamy) Dariba Kalan, the bustling, narrow street that is home to the perfumery, is just off Chandhi Chowk, Old Delhiʼs main thoroughfare. The old city, first built in 1659, is the walled former capital of the erstwhile Mughal Empire, and Chandni Chowk was once a wide and graceful boulevard bisected by a canal and dotted with intricate buildings. But now, its former beauty has been swallowed up by the masses. When I arrived at Gulab Singh Johrimal at 10 am, the street was teeming with cars, buses and rickshaws, humans, horses and the occasional goat also trying to carve out space. The shop was barely distinguishable from the outside. Its interior was unadorned and functional – a handful of men sat behind a counter, waiting on customers.