Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National Oceanic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

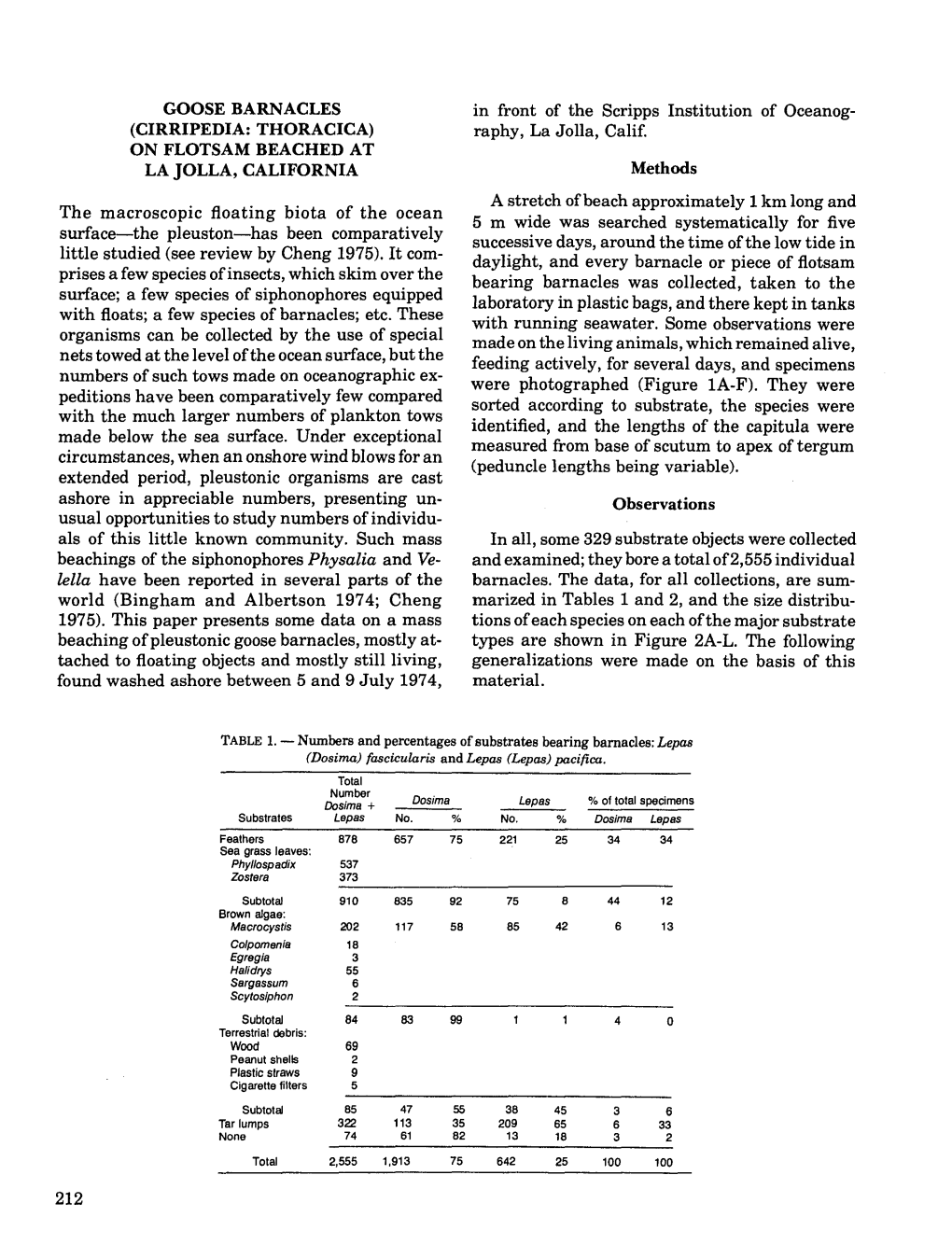

-

Dosima Fascicularis (Ellis & Solander, 1786) (Crustacea, Cirripedia) from the Galician Istributio D

Check List 10(3): 669–671, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution N First record of the buoy barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Ellis & Solander, 1786) (Crustacea, Cirripedia) from the Galician ISTRIBUTIO D * RAPHIC G beaches (NW Spain) after the Prestige oil spill EO G Juan Junoy and Jorge Junoy N O EU-US Marine Biodiversity [email protected] Group, Franklin Institute and Departamento de Ciencias de la Vida, AP 20. Campus Universitario, Universidad de Alcalá, 28805 Alcalá de Henares, Spain. OTES * Corresponding author. E-mail: N Abstract: Dosima fascicularis The presence of the buoy barnacle is first documented for Spanish waters. More than the half of the specimens collected was attached to tar pellets from the Prestige oil spill. DOI: 10.15560/10.3.669 Dosima fascicularis (Ellis & Solander, 1786) is a presumablycollected along from the the 1470 Prestige m of oil the spill; beach other longitude. attachment The stalked barnacle which capitulum bears five large plates. surfacesfloats of 53.8%were Velellaof the specimens were Sargassumattached to bladderstar balls, It is the unique barnacle that constructs its own float, a attachmentfoamy mass surfaces described (Darwin as similar 1851; to Minchin polystyrene, 1996; usingRyan tests (15.3%), floating items as feathers, tar balls and plastic particles as (7.6%) and feathers (2.5%). 20.8% of buoy barnacles lacked an obvious attachment object (Figure 2). theand BritishBranch Islands2012). The and species Baltic Seais widespread (Darwin 1851) in temperate but its sizeThe recorded average for thecapitulum species lengthwas 37 ofmm the in Europeancollected presenceand subtropical in European ocean waters,coast is reaching unusual in(O’ the Riodan NE Atlantic 1967; specimens was 17.7 mm (range 13–22 mm). -

Marine Litter As Habitat and Dispersal Vector

Chapter 6 Marine Litter as Habitat and Dispersal Vector Tim Kiessling, Lars Gutow and Martin Thiel Abstract Floating anthropogenic litter provides habitat for a diverse community of marine organisms. A total of 387 taxa, including pro- and eukaryotic micro- organisms, seaweeds and invertebrates, have been found rafting on floating litter in all major oceanic regions. Among the invertebrates, species of bryozoans, crus- taceans, molluscs and cnidarians are most frequently reported as rafters on marine litter. Micro-organisms are also ubiquitous on marine litter although the compo- sition of the microbial community seems to depend on specific substratum char- acteristics such as the polymer type of floating plastic items. Sessile suspension feeders are particularly well-adapted to the limited autochthonous food resources on artificial floating substrata and an extended planktonic larval development seems to facilitate colonization of floating litter at sea. Properties of floating litter, such as size and surface rugosity, are crucial for colonization by marine organ- isms and the subsequent succession of the rafting community. The rafters them- selves affect substratum characteristics such as floating stability, buoyancy, and degradation. Under the influence of currents and winds marine litter can transport associated organisms over extensive distances. Because of the great persistence (especially of plastics) and the vast quantities of litter in the world’s oceans, raft- ing dispersal has become more prevalent in the marine environment, potentially facilitating the spread of invasive species. T. Kiessling · M. Thiel Facultad Ciencias del Mar, Universidad Católica del Norte, Larrondo 1281, Coquimbo, Chile L. Gutow Biosciences | Functional Ecology, Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven, Germany M. -

Download PDF File

Scientific Note Record of coastal colonization of the Lepadid goose barnacle Lepas anatifera Linnaeus, 1758 (Crustacea: Cirripedia) at Arraial do Cabo, RJ 1 1,2 LUIS FELIPE SKINNER & DANIELLE FERNANDES BARBOZA 1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Laboratório de Ecologia e Dinâmica Bêntica Marinha, São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro. Rua Francisco Portela 1470, Patronato, São Gonçalo, RJ. 24435-005. 2Bolsista PROATEC, UERJ. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this note we record the occurence of Lepas anatifera (Cirripedia) on the hull of a coastal supply boat that operates only in restricted inshore waters of Arraial do Cabo. This species is usually found on tropical and subtropical oceanic waters and, at region, could be classified as transient species. Key words: marine fouling, barnacle, recruitment, inshore transport, species distribution, Cabo Frio upwelling Resumo. Registro de colonização costeira da craca pedunculada Lepas anatifera Linnaeus, 1758 (Crustacea: Cirripedia) na costa de Arraial do Cabo, RJ. Nesta nota nós registramos a ocorrência de Lepas anatifera (Cirripedia) no casco de uma pequena embarcação que opera exclusivamente em águas costeiras de Arraial do Cabo. Esta espécie é típica de águas oceânicas de regiões tropicais e subtropicais e pode ser classificada como transiente na região. Palavras chave: incrustação marinha, craca, recrutamento, transporte costeiro, distribuição de espécies, ressurgência de Cabo Frio Lepas anatifera Linnaeus, 1758 (Fig. 1) is a and not by larval preference. pedunculate goose barnacle with cosmopolitan At Cabo Frio region is frequent to find many distribution (Young 1990, 1998). They are found individuals that arrived to the coast on floating mainly on oceanic waters from tropical and debris. -

The Genus Hippolyte Leach, 1814

The genus Hippolyte Leach, 1814 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Cari- dea: Hippolytidae) in the East Atlantic Ocean and the Medi- terranean Sea, with a checklist of all species in the genus C. d'Udekem d'Acoz Udekem d'Acoz, C. d'. The genus Hippolyte Leach, 1814 (Crustacea; Decapoda; Caridea; Hippolytidae) in the East Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, with a checklist of all species in the genus. Zool. Verh. Leiden 303, 30.ix.1996: 1-133, figs 1-50, tab. 1.—ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-45-1. C. d'Udekem d'Acoz, Avenue du bois des collines 34, 1420 Braine-l'Alleud, Belgium. [Research Asso- ciate at the Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Brussels]. Key words: Crustacea; Decapoda; Caridea; Hippolytidae; Hippolyte; shrimp; systematics; discontinu- ous variations; neoteny; ecology; East Atlantic; Mediterranean; world species list. The genus Hippolyte Leach in the East Atlantic and the Mediterranean is revised and a list of the world species is given. Eleven species occur in the area studied: H. coerulescens (Fabricius), H. garciarasoi spec. nov., H. inermis Leach, H. lagarderei d'Udekem d'Acoz, H. leptocerus (Heller), H. leptometrae Ledoyer, H. niezabitowskii spec. nov., H. palliola Kensley, H. prideauxiana Leach, H. sapphica d'Udekem d'Acoz, H. varians Leach. An elaborate key, complete descriptions and illustrations of all species are provided, while their ecology is discussed in detail. A morphological account is also given for the spe- cies occuring in the Suez Canal: H. proteus (Paulson) and H. ventricosa H. Milne Edwards. It is shown that H. prideauxiana (previously H. huntii) and H. -

Macquarie University PURE Research Management System

Macquarie University PURE Research Management System This is the Accepted Manuscript version of the following article: Shine, R., Goiran, C., Shilton, C., Meiri, S., Brown, G. P. (2020) The life aquatic: an association between habitat type and skin thickness in snakes. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 128, no. 4, pp. 975–986. which has been published in final form at: Access to the published version: https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz136 Version archived for private and non-commercial use with the permission of the author/s and according to publisher conditions. For further rights please contact the publisher. 1 The Life Aquatic: an association between habitat type and 2 skin thickness in snakes 3 4 RICHARD SHINE1*, CLAIRE GOIRAN2, CATHERINE SHILTON3, 5 SHAI MEIRI4,5 and GREGORY P. BROWN1 6 7 1Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, NSW 2019, Australia 8 2LabEx Corail & ISEA, Université de la Nouvelle-Calédonie, BP R4, 98851 Nouméa cedex, 9 New Caledonia 10 3Berrimah Veterinary Laboratories, Northern Territory Department of Primary Industry and 11 Resources, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia 12 4School of Zoology, Tel-Aviv University, 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel 13 5The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel-Aviv University, 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel 14 15 *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 16 17 SHORT RUNNING TITLE: SKIN THICKNESS IN SNAKES 18 19 20 21 Manuscript for consideration in Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 22 3 July 2019 23 1 24 25 An aquatic animal faces challenges not encountered by its terrestrial counterparts, promoting 26 adaptive responses in multiple traits. -

`Degraded' RNA Profiles in Arthropoda and Beyond

‘Degraded’ RNA profiles in Arthropoda and beyond Sean D. McCarthy, Michel M. Dugon and Anne Marie Power School of Natural Sciences, Ryan Institute for Environmental, Marine and Energy Research, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland ABSTRACT The requirement for high quality/non-degraded RNA is essential for an array of molecular biology analyses. When analysing the integrity of rRNA from the barnacle Lepas anatifera (Phylum Arthropoda, Subphylum Crustacea), atypical or sub- optimal rRNA profiles that were apparently degraded were observed on a bioanalyser electropherogram. It was subsequently discovered that the rRNA was not degraded, but arose due to a ‘gap deletion’ (also referred to as ‘hidden break’) in the 28S rRNA. An apparent excision at this site caused the 28S rRNA to fragment under heat- denaturing conditions and migrate along with the 18S rRNA, superficially presenting a ‘degraded’ appearance. Examination of the literature showed similar observations in a small number of older studies in insects; however, reading across multiple disciplines suggests that this is a wider issue that occurs across the Animalia and beyond. The current study shows that the 28S rRNA anomaly goes far beyond insects within the Arthropoda and is widespread within this phylum. We confirm that the anomaly is associated with thermal conversion because gap-deletion patterns were observed in heat-denatured samples but not in gels with formaldehyde-denaturing. Subjects Aquaculture, Fisheries and Fish Science, Genomics, Marine Biology, Taxonomy, Zoology Keywords Hidden break, Denaturing, Taxonomy, Gap deletion, Degraded rNA, Bioanalyser Submitted 4 July 2015 Accepted 4 November 2015 INTRODUCTION Published 1 December 2015 Anomalies in the gel migration of the 28S subunit rRNA in denatured samples have Corresponding author mostly appeared in the older literature (Applebaum, Ebstein& Wyatt, 1966 ; Ishikawa& Anne Marie Power, [email protected] Newburgh, 1972; Fujiwara& Ishikawa, 1986 ). -

Biological and Biomimetic Adhesives Mons, 18-20 May 2011

COST Action TD0906 nd 2 scientific meeting Biological and Biomimetic Adhesives Mons, Belgium 18-20 May 2011 www.cost-bioadhesives.org Biological and Biomimetic Adhesives Mons, 18-20 May 2011 Programme overview Wednesday May 18 th Oral sessions and Management Committee meeting will be held in the Gutenberg auditorium. Coffee breaks, lunch, and poster session will take place in the Plisnier Hall. 08:00 - 09:15 Registration 09:15 - 09:30 Welcome talks 09:30 - 10:30 Oral communications (Chairman: Markus Linder) 9:30 Janek von Byern “Gluing to survive-Antipredator strategy of salamanders” 9:50 Mustafa O. Guler “Dopa functionalized peptide nanofibers for metal implant surface bioactivation” 10:10 Peter Ladurner “Macrostomum lignano as a model system to study duo-gland adhesive organs of flatworms” 10:30 – 11:00 Coffee break 11:00 – 12:00 Oral communications (Chairwoman: Marisa Almeida) 11:00 Peter Kasak “Zwitterionic polymer as tool against biofouling” 11:20 Markus Linder “Biological adhesives as building blocks in nanomaterials” 11:40 Jon Barnes “Wet but non slippery: bioinspired adhesives that work in humid and flooded conditions 12:00 – 13:30 Lunch 13:30 – 15:00 COST Management Committee meeting (Everybody can join but only the Management Committee is allowed to vote) 15:00 – 15:30 Coffee break 15:30 – 17:30 Poster session Thursday May 19 th Oral sessions and Management Committee meeting will be held in the Curie auditorium. Coffee breaks, lunch, and poster session will take place in the Plisnier Hall. 09:30 - 10:30 Oral communications (Chairman: Janek von Byern) 9:30 Bjoern Melzer “The climbing roots of Vanilla spec. -

Symbionts of Marine Medusae and Ctenophores

Plankton Benthos Res 4(1): 1–13, 2009 Plankton & Benthos Research © The Plankton Society of Japan Review Symbionts of marine medusae and ctenophores SUSUMU OHTSUKA1*, KAZUHIKO KOIKE2, DHUGAL LINDSAY3, JUN NISHIKAWA4, HIROSHI MIYAKE5, MASATO KAWAHARA2, MULYADI6, NOVA MUJIONO6, JURO HIROMI7 & HIRONORI KOMATSU8 1 Takeahara Marine Science Station, Setouchi Field Science Center, Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University, 5–8–1 Minato-machi, Takehara, Hiroshima 725–0024, Japan 2 Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University, 1–4–4 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739–8528, Japan 3 Japan Agency for Marine-Earth-Science and Technology, 2–15 Natsushima-cho, Yokosuka, Kanagawa 237–0661, Japan 4 Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo, 1–15–1 Minamidai, Nakano, Tokyo 164–8639, Japan 5 School of Marine Biosciences, Kitasato University, 160–4 Azaudou, Okirai, Sanriku-cho, Ohunato, Iwate 022–0101, Japan 6 Division of Zoology, Research Center for Biology, LIPI, Gedung Widyasatwaloka, Jl Raya, Jakarta-Bogor Km 46, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia 7 College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, 1866 Kameino, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 252–8510, Japan 8 Department of Zoology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 3–23–1 Hyakunin-cho, Shinjuku, Tokyo 169–0073, Japan Received 3 September 2008; Accepted 26 November 2008 Abstract: Since marine medusae and ctenophores harbor a wide variety of symbionts, from protists to fish, they con- stitute a unique community in pelagic ecosystems. Their symbiotic relationships broadly range from simple, facultative phoresy through parasitisim to complex mutualism, although it is sometimes difficult to define these associations strictly. Phoresy and/or commensalism are found in symbionts such as pycnogonids, decapod larvae and fish juveniles. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „Characterization of the cement of the stalked barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Crustacea, Cirripedia Thoracica): Morphology, biochemistry and mechanical properties“ verfasst von Mag.rer.nat. Vanessa Zheden angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften (Dr.rer.nat.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 091 439 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Zoologie Betreut von: Ao. Univ.-Prof. i.R. Dr. Waltraud Klepal “If you can dream it, you can do it.” Walt Disney Table of contents I. Introduction 1 II. Manuscript 1 9 Zheden V, von Byern J, Kerbl A, Leisch N, Staedler Y, Grunwald I, Power AM, Klepal W. 2012. Morphology of the cement apparatus and the cement of the buoy barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Crustacea, Cirripedia, Thoracica, Lepadidae). Biol Bull. 223:192-204. III. Manuscript 2 23 Zheden V, Klepal W, von Byern J, Bogner FR, Thiel K, Kowalik T, Grunwald I. 2014. Biochemical analyses of the cement float of the goose barnacle Dosima fascicularis - a preliminary study. Biofouling. 30:949-963. IV. Manuscript 3 39 Zheden V, Klepal W, Gorb SN, Kovalev A. Mechanical properties of the cement of the stalked barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Cirripedia, Crustacea). Interface Focus. Submitted V. Manuscript 4 63 Zheden V, Kovalev A, Gorb SN, Klepal W. Characterization of cement float buoyancy in the stalked barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Crustacea, Cirripedia). Interface Focus. Submitted VI. Discussion 81 VII. Abstract 87 VIII. Zusammenfassung 88 IX. Acknowledgements 89 X. Curriculum Vitae 90 “Characterization of the cement of the stalked barnacle Dosima fascicularis (Crustacea, Cirripedia Thoracica): Morphology, biochemistry and mechanical properties“ I. Introduction Barnacles (Cirripedia Thoracica) are sessile, marine Crustacea, which comprise acorn (Sessilia) and stalked barnacles (Pedunculata). -

The Geochemistry of Modern Calcareous Barnacle Shells and Applications for Palaeoenvironmental Studies

The geochemistry of modern calcareous barnacle shells and applications for palaeoenvironmental studies Ullmann, C. V.; Gale, A. S.; Haggett, J.; Wray, D.; Frei, R.; Korte, C.; Broom-Fendley, S.; Littler, K.; Hesselbo, S. P. Published in: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2018.09.010 Publication date: 2018 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Ullmann, C. V., Gale, A. S., Haggett, J., Wray, D., Frei, R., Korte, C., Broom-Fendley, S., Littler, K., & Hesselbo, S. P. (2018). The geochemistry of modern calcareous barnacle shells and applications for palaeoenvironmental studies. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 243, 149-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.09.010 Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 243 (2018) 149–168 www.elsevier.com/locate/gca The geochemistry of modern calcareous barnacle shells and applications for palaeoenvironmental studies C.V. Ullmann a,⇑, A.S. Gale b, J. Huggett c, D. Wray d, R. Frei e, C. Korte e S. Broom-Fendley a, K. Littler a, S.P. Hesselbo a a University of Exeter, Camborne School of Mines and Environment and Sustainability Institute, Treliever Road, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK b University of Portsmouth, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Burnaby Building, Burnaby Road, Portsmouth PO1 3QL, UK c Petroclays, The Oast House, Sandy Cross Lane, Heathfield, Sussex TN21 8QP, UK d University of Greenwich, School of Science, Pembroke, Chatham Maritime, Kent ME4 4TB, UK e University of Copenhagen, Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, Øster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen, Denmark Received 14 March 2018; accepted in revised form 12 September 2018; available online 22 September 2018 Abstract Thoracican barnacles of the Superorder Thoracicalcarea Gale, 2016 are sessile calcifiers which are ubiquitous in the inter- tidal zone and present from very shallow to the deepest marine environments; they also live as epiplankton on animals and detritus. -

A Synopsis of the Literature on the Turtle Barnacles (Cirripedia: Balanomorpha: Coronuloidea) 1758-2007

EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 1 (ERC-SP1) A SYNOPSIS OF THE LITERATURE ON THE TURTLE BARNACLES (CIRRIPEDIA: BALANOMORPHA: CORONULOIDEA) 1758-2007 COMPILED BY: THE EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE ©2007 CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE EPIBIONT RESEARCH COOPERATIVE ARNOLD ROSS (founder)† GEORGE H. BALAZS Scripps Institution of Oceanography NOAA, NMFS Marine Biology Research Division Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center LaJolla, California 92093-0202 USA 2570 Dole Street †deceased Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 USA [email protected] MICHAEL G. FRICK Assistant Director/Research Coordinator THEODORA PINOU Caretta Research Project Assistant Professor 9 Sandy Creek Court Secondary Science Education Savannah, Georgia 31406 USA Coordinator [email protected] Department of Biological & 912 308-8072 Environmental Sciences Western Connecticut State University JOHN D. ZARDUS 181 White Street Assistant Professor Danbury, Connecticut 06810 USA The Citadel [email protected] Department of Biology 203 837-8793 171 Moultrie Street Charleston, South Carolina 29407 USA ERIC A. LAZO-WASEM [email protected] Division of Invertebrate Zoology 843 953-7511 Peabody Museum of Natural History Yale University JOSEPH B. PFALLER P.O. Box 208118 Florida State University New Haven, Connecticut 06520 USA Department of Biological Sciences [email protected] Conradi Building Tallahassee, Florida 32306 USA CHRIS LENER [email protected] Lower School Science Specialist 850 644-6214 Wooster School 91 Miry Brook Road LUCIANA ALONSO Danbury, Connecticut 06810 USA Universidad de Buenos Aires/Karumbé [email protected] H. Quintana 3502 203 830-3996 Olivos, Buenos Aires 1636 Argentina [email protected] KRISTINA L. WILLIAMS 0054-11-4790-1113 Director Caretta Research Project P.O. -

Environmental Impact Assessment 12 July 2021

The Ocean Cleanup Final Environmental Impact Assessment 12 July 2021 Prepared for: Prepared by: The Ocean Cleanup CSA Ocean Sciences, Inc. Batavierenstraat 15, 4-7th floor 8502 SW Kansas Avenue 3014 JH Rotterdam Stuart, Florida 34997 The Netherlands United States THE OCEAN CLEANUP DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT DOCUMENT NO. CSA-THEOCEANCLEANUP-FL-21-81581-3648-01-REP-01-FIN-REV01 Internal review process Version Date Description Prepared by: Reviewed by: Approved by: J. Tiggelaar Initial draft for A. Lawson B. Balcom INT-01 04/20/2021 K. Olsen science review G. Dodillet R. Cady K. Olen J. Tiggelaar INT-02 04/24/2021 TE review K. Metzger K. Olsen K. Olen Client deliverable Version Date Description Project Manager Approval 01 04/27/2021 Draft Chapters 1-4 K. Olsen Combined 02 05/07/2021 K. Olsen deliverable Incorporation of The Ocean Cleanup and 03 05/17/2021 K. Olsen Neuston Expert Comments Incorporate legal FIN 07/09/2021 comments and add K. Olsen additional 2 cruises FIN REV01 07/12/2021 Revised Final K. Olsen The electronic PDF version of this document is the Controlled Master Copy at all times. A printed copy is considered to be uncontrolled and it is the holder’s responsibility to ensure that they have the current version. Controlled copies are available upon request from the CSA Document Production Department. Executive Summary BACKGROUND The Ocean Cleanup has developed a new Ocean System (S002) which is made by a Retention System (RS) comprising two wings of 391 m in length each and a Retention Zone (RZ), that will be towed by two vessels to collect buoyant plastic debris from the within the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) located roughly midway between California and Hawaii.