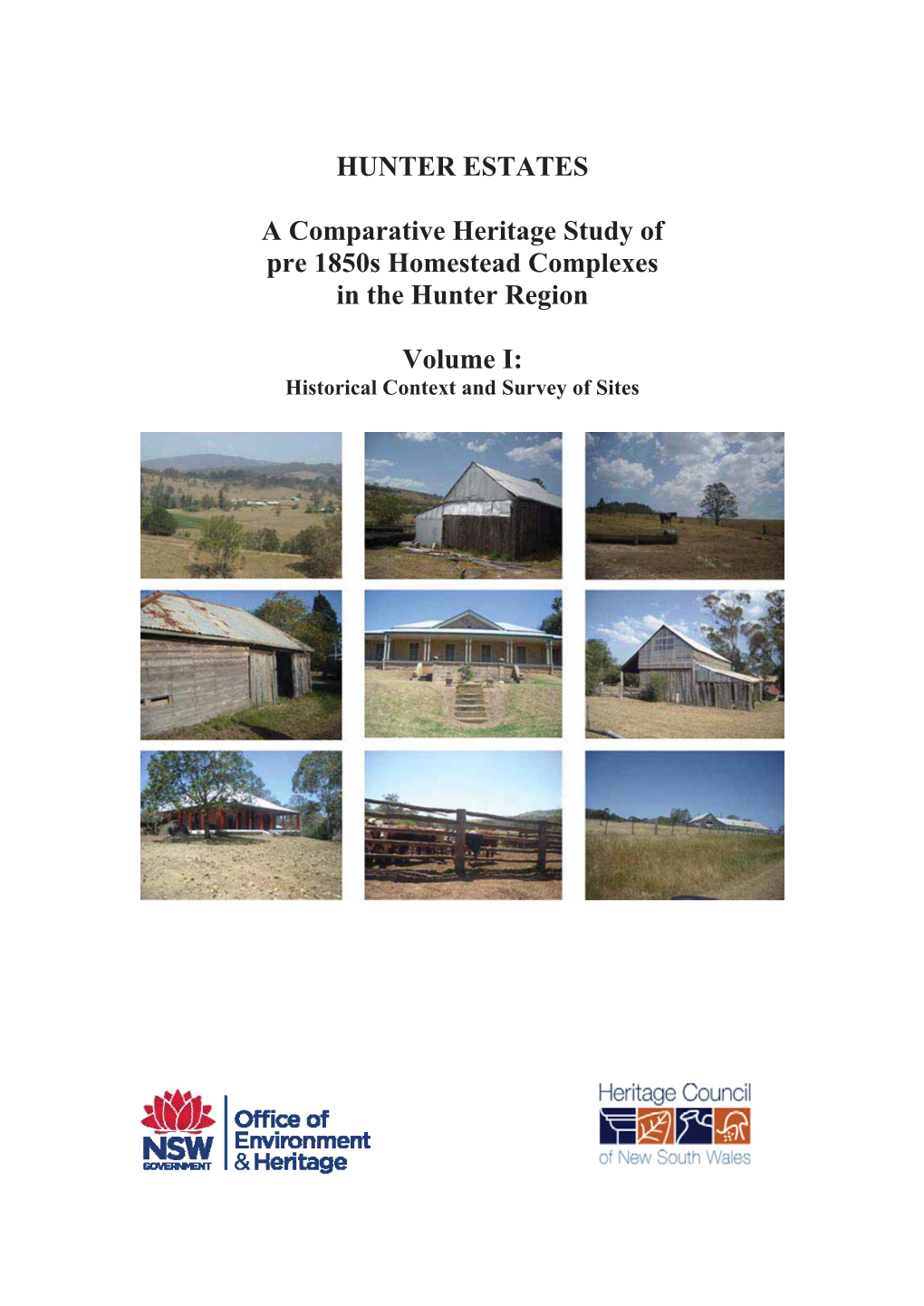

Hunter Estates a Comparative Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model Of

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model of Creativity through documentary video and online practice Susan Kerrigan BArts (Comm Studies) (UoN), Grad Cert Practice Tertiary Teaching (UoN) A creative work thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication & Media Arts University of Newcastle, June 2011 Declarations: Declaration 1: I hereby certify that some elements of the creative work Using Fort Scratchley which has been submitted as part of this creative PhD thesis were created in collaboration with another researcher, Kathy Freeman, who worked on the video documentary as the editor. Kathy was working at the Honours level from 2005 to 2006 and I was her Honours Supervisor. Kathy was researching the creative role of the editor, her Honours research was titled Expanding and Contracting the role of the Editor: Investigating the role of the editor in the collaborative and creative procedure of documentary film production (Freeman, 2007). While Kathy’s work dovetailed closely with my own work there was a clear separation of responsibilities and research imperatives, as each of our research topics was focussed on the creative aspects of our different production crew roles. Declaration 2: I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis contains one journal publication and three peer-reviewed published conference papers authored by myself. Kerrigan, S. (2010) Creative Practice Research: Interrogating creativity theories through documentary practice TEXT October 2010. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, Special Issue Number 8, from http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue8/content.htm Kerrigan, S. (2009) Applying creativity theories to a documentary filmmaker’s practice Aspera 2009 - Beyond the Screen: Retrieved from http://www.aspera.org.au/node/40 Kerrigan, S. -

Kooragang Wetlands: Retrospective of an Integrated Ecological Restoration Project in the Hunter River Estuary

KOORAGANG WETLANDS: RETROSPECTIVE OF AN INTEGRATED ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION PROJECT IN THE HUNTER RIVER ESTUARY P Svoboda Hunter Local Land Services, Paterson NSW Introduction: At first glance, the Hunter River estuary near Newcastle NSW is a land of contradictions. It is home to one of the world’s largest coal ports and a large industrial complex as well as being the location of a large internationally significant wetland. The remarkable natural productivity of the Hunter estuary at the time of European settlement is well documented. Also well documented are the degradation and loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat in the estuary due to over 200 years of draining, filling, dredging and clearing (Williams et al., 2000). However, in spite of extensive modification, natural systems of the estuary retained enough value and function for large areas to be transformed by restoration activities that aimed to show industry and environmental conservation could work together to their mutual benefit. By establishing partnerships and taking a collaborative and adaptive approach, the project was able to implement restoration and related activities on a landscape basis, working across land ownership and management boundaries (Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project, 2010). The Kooragang Wetland Rehabilitation Project (KWRP) was launched in 1993 to help compensate for the loss of fisheries and other wildlife habitat at suitable sites in the Hunter estuary. This paper revisits the expectations and planning for the project as presented in a paper to the INTECOL’s V international wetlands conference in 1996 (Svoboda and Copeland, 1998), reviews the project’s activities, describes outcomes and summarises issues faced and lessons learnt during 24 years of implementing a large, long-term, integrated, adaptive and community-assisted ecological restoration project. -

FINAL NCIG SEE Report April 2020

Coal Export Terminal Optimisation Statement of Environmental Effects Project Approval (06_0009) Modification Report APRIL 2020 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 5 Engagement 22 1.1 Background 1 5.1 Consultation 22 1.1.1 NCIG Development History 1 5.1.1 Department Of Planning, Industry and Environment 22 1.1.2 Description of Approved Operations 4 5.1.2 Regulatory Agencies and Local Council 22 1.1.3 Optimisation Initiatives Implemented at the NCIG CET 6 5.1.3 Other Key Stakeholders 22 1.2 Modification Overview 8 5.1.4 Public Consultation 23 1.3 Interactions with other Projects 9 5.2 Key Comments and Concerns 23 1.4 Structure of this Modification Report 9 6 Assessment Of Impacts 25 6.1 Noise 25 2 Description Of The Modification 10 6.1.1 Methodology 25 2.1 Train Movements 10 6.1.2 Background 25 2.2 Ships 10 6.1.3 Applicable Criteria 27 2.3 Water Management 10 6.1.4 Impact Assessment Review 29 6.2 Air Quality 32 3 Strategic Context 12 6.2.1 Methodology 32 3.1 Optimisation Of Existing Infrastructure 12 6.2.2 Background 32 3.2 Benefits For NCIG’s Customers 12 6.2.3 Impact Assessment Review 35 3.3 Importance to Port of Newcastle 13 6.3 Greenhouse Gas Emissions 36 3.4 Hunter Valley Coal Chain Efficiency 14 6.3.1 Assessment of Potential Greenhouse Gas Emissions 36 4 Statutory Context 15 6.3.2 International, National and State Policies and Programs Regarding Greenhouse 4.1 Environmental Planning and Gas Emissions 37 Assessment Act, 1979 15 6.3.3 NCIG Greenhouse Gas Mitigation 4.1.1 EP&A Act Objects 16 Measures 38 4.2 Environmental Planning Instruments 17 4.2.1 State Environmental Planning Policy 7 Evaluation Of Merits 39 (Three Ports) 2013 17 7.1 Stakeholder Engagement Overview 39 4.2.2 State Environmental Planning Policy 7.2 Consolidated Summary of Assessment (Coastal Management) 2018 19 of Impacts 39 4.2.3 State Environmental Planning Policy No. -

Hunter Valley: Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission 8 November 2013

Director Assessment Policy, Systems & Stakeholder Engagement Department of Planning and Infrastructure Hunter Valley: Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission 8 November 2013 Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission: Hunter Valley This page was intentionally left blank 2 Coal Seam Gas Exclusion Zones Submission: Hunter Valley Foreword Closing the loop on CSG Mining in the Hunter Valley When it comes to coal seam gas (CSG) mining, protecting Australia’s most visited wine tourism region in its entirety - not in parts - is of paramount importance. And the time to do it is now. The NSW State Government should be recognised for delivering on its pre-election promises to preserve the Hunter Valley wine tourism region from CSG mining by confirming exclusion zones around the villages of Broke and Bulga as well as around significant areas defined as Viticulture Critical Industry Clusters (VCIC). But protecting most of the region, while leaving several critical areas open for CSG exploration and mining, could have devastating consequences for the iconic Hunter region as a whole – and undo the Government’s efforts thus far. While mining is obviously a legitimate land use and an important revenue source, this can’t justify allowing mining activities in areas where other existing, profitable industries would be adversely affected. Put simply, winemaking, tourism and CSG mining are not compatible land uses. The popularity and reputation of the Hunter Valley wine tourism region is fundamentally connected to the area’s natural beauty and landscape – and that natural beauty will fast disappear if the countryside is peppered with unsightly gas wells. Research reveals 80%1 of Hunter Valley visitors don’t want to see gas wells in the wine and tourism region, with 70%2 saying if gas wells are established they’ll just stop coming. -

Derailment and Collision Between Coal Trains Ravenan (25Km from Muswellbrook), New South Wales, on 26 September 2018

Derailment and collision between coal trains Ravenan (25km from Muswellbrook), New South Wales, on 26 September 2018 ATSB Transport Safety Report Rail Occurrence Investigation (Defined) RO-2018-017 Final – 18 December 2020 Cover photo: Source ARTC This investigation was conducted under the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (Commonwealth) by the Office of Transport Safety Investigations (NSW) on behalf of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau in accordance with the Collaboration Agreement Released in accordance with section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, ACT 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 2463 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Email: [email protected] Website: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. -

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

Dungog Area Birding Route

Hunter Region of NSW–Barrington Southern Slopes 5 CHICHESTER DAM 7 UPPER ALLYN RIVER There are several picnic areas available The Upper Allyn River rainforests start and also toilet facilities. Walking the 10km past the junction of Allyn River road between the first picnic areas and Road and Salisbury Gap Road (and those further down below the dam wall 40km from East Gresford). Here you can be very productive. will find many locations that offer There are generally not many water birds good birdwatching opportunities. Dungog on the dam but cormorants, egrets and Noisy Pitta (in summer), Superb coot are the more common. Hoary- Lyrebird, Eastern Whipbird and headed Grebe, Black Swan and White-browed and Large-billed Musk Duck are also possible. Scrubwren can easily be seen. Area Birding You won’t miss the bell-like Check the fig trees for pigeons and calls of the Bell Miner bowerbirds. The roads are good for colony in the vicinity. The dam finding Wonga Pigeons, and if you area is secured overnight by Powerful Owl are lucky, an Emerald Dove. Route a locked gate and opening There are several places worth checking along Allyn hours are: River Forest Road, particularly at the river crossings. HUNTER REGION 8am to 4pm – Mon to Fri Allyn River Forest Park and the nearby White Rock 8.30am to 4.30pm – Sat & Sun Camping Area are also recommended, and there Rufous Fantail is the possibility of finding a Sooty Owl at night and a Paradise Riflebird by day. Note that these sites 6 BLUE GUM LOOP TRAIL Barrington This popular 3.5km loop track starts from the Williams River are often crowded during school holidays and public Southern Slopes picnic area which lies 500m to the east of the end of the holiday weekends. -

Goulburn River National Park and Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve

1 GOULBURN RIVER NATIONAL PARK AND MUNGHORN GAP NATURE RESERVE PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service February 2003 2 This plan of management was adopted the Minister for the Environment on 6th February 2003. Acknowledgments: This plan was prepared by staff of the Mudgee Area of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The assistance of the steering committee for the preparation of the plan of management, particularly Ms Bev Smiles, is gratefully acknowledged. In addition the contributions of the Upper Hunter District Advisory Committee, the Blue Mountains Region Advisory Committee, and those people who made submissions on the draft plan of management are also gratefully acknowledged. Cover photograph of the Goulburn River by Michael Sharp. Crown Copyright 2003: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. 3 ISBN 0 7313 6947 5 4 FOREWORD Goulburn River National Park, conserving approximately 70 161 hectares of dissected sandstone country, and the neighbouring Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve with its 5 935 hectares of sandstone pagoda formation country, both protect landscapes, biology and cultural sites of great value to New South Wales. The national park and nature reserve are located in a transition zone of plants from the south-east, north-west and western parts of the State. The Great Dividing Range is at its lowest elevation in this region and this has resulted in the extension of many plants species characteristic of further west in NSW into the area. In addition a variety of plant species endemic to the Sydney Sandstone reach their northern and western limits in the park and reserve. -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Australian Agricultural Company IS

INDEX Abbreviations A. A. Co.: Australian Agricultural Company I. S.: Indentured Servant Note: References are to letter numbers not page numbers. A. A. Co.: Annual Accounts of, 936; Annual James Murdoch, 797, 968; Hugh Noble, Report of, 1010; and letter of attorney 779; G. A. Oliver, 822; A. P. Onslow, empowering Lieutenant Colonel Henry 782; George T. Palmer, 789, 874; John Dumaresq to act as Commissioner of, Paul, 848; John Piper, senior, 799, 974; 1107; Quarterly Accounts of, 936; value of James Raymond, 995; separate, for supply property of at 3 April 1833, 980; see also of coal to Colonial Department and to stock in A. A. Co. Commissariat Department, 669, 725, 727; A. A. Co. Governor, London, see Smith, John: Benjamin Singleton, 889; William Smyth, A. A. Co. Stud, 706a, 898, 940d 759; Samuel Terry, 780; Thomas Walker, Aborigines: allegations of outrages against by 784, 811; William Wetherman, 917; T. B. Sir Edward Parry and others in employ of Wilson, 967; Sir John Wylde, 787, 976 A. A. Co., 989, 1011a, 1013; alleged offer ‘Act for preventing the extension of the of reward for heads of, 989; engagement of infectious disease commonly called the as guide for John Armstrong during survey, Scab in Sheep or Lambs’ (3 William IV No. 1025; and murder of James Henderson, 5, 1832) see Scab Act 906; number of, within limits of A. A. Co. Adamant: convicts on, 996, 1073 ‘s original grant, 715; threat from at Port advertisements; see under The Australian; Stephens, 956 Sydney Gazette; Sydney Herald; Sydney accidents, 764a Monitor accommodation: for A. -

Thematic History

DUNGOG SHIRE HERITAGE STUDY THEMATIC HISTORY by GRACE KARSKENS B.A., M.A. prepared for PERUMAL, WRATHALL and MURPHY PTY LTD ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNERS in association with CAMERON MCNAMARA March, 1986 Accompanying Volumes Final Report Specialist Reports DUNGOG HERITAGE STUDY THEMATIC HISTORY Prepared by: Perumal Murphy Pty. Ltd in association with Cameron McNamara For Dungog Shire Council Heritage Council of NSW July 1988 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following persons and organizations for their assistance and advice. Archives Authority of N.S.W. Mr. Cameron Archer, Paterson Mrs. Pauline Clements, Paterson Mr. Reg Ford, Clarence Town Mrs. Marie Grogan, Dungog Mr. Brian Hartcher, Dungog Shire Council Mr. Don McLaren, Dungog Mitchell Library, Sydney Newcastle Local History Library Mr. Bryan Spencer, Gresford Mr. Jack Sullivan, Merewether CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Theme 1 : The Natural Environment 2 Theme 2 : The Aborigines 10 Theme 3 : Discovery, Exploration and Early Settlement 16 Theme 4 : The First Wave: Land Settlement 1820 - c1836 23 Theme 5 : The Early Government Influence 49 Theme 6 : The Growth of Towns and Transport Networks 61 Theme 7 : The Development of Communities 123 Theme 8 : Industries 151 Theme 9 : Post-war Period : Looking Back for the Future 200 INTRODUCTION The history of Dungog Shire presents a vivid kaleidoscope of the movement of peoples, the enterprise of individuals, the impact of economic conditions and of technological innovations, the rise and decline of towns, and the development of strong communities. The factors are interacting; the fabric of the past is closely woven. In this attempt to understand the Shire's past, and thus its present landscapes and material culture, the subject has been divided into nine themes focusing on key aspects of the Shire's development, and these themes are interrelated in order to reflect the past holistically, as a "fabric". -

Upper Hunter River and Dam Levels

Upper Hunter river and dam levels UPPER Hunter river levels have risen after significant rainfall and periods of flash flooding brought on by a combination of higher than average rainfall and thunderstorms during December 2020. See river and dam levels below Although the Hunter has not been on constant flood watch compared to north coast areas, there has been enough downpour and thunderstorms to bring flash flooding to the region. The La Niña weather event brought initial widespread rainfall and more thunderstorms are predicted throughout January 2021. Level 2 water restrictions are to remain for Singleton water users, with the Glennies Creek Dam level currently sitting at 43.4 percent. Dam levels: Glennies Creek Dam: Up 0.5 percent capacity compared to last week. Now 43.4 percent full and contains 123,507 millilitres of water; Lockstock Dam: Down 3.9 percent capacity compared to last week. Now 101.5 percent full and contains 20,522 millilitres of water; Glenbawn Dam: Up 0.4 percent capacity compared to last week. Now 49.5 percent full and contains 371,620 millilitres of water River levels (metres): Hunter River (Aberdeen): 2.37 m Hunter River (Denman): 1.924 m Hunter River (Muswellbrook): 1.37 m Hunter River (Raymond Terrace): 0.528 m Hunter River (Glennies Creek): 3.121 m Hunter River (Maison Dieu): 3.436 m Hunter River (Belltrees): 0.704 m Paterson River: 1.984 m Williams River (Dungog): 2.616 m Pages River: 1.311 m Moonan Brook: 0.862 m Moonan Dam: 1.147 m Rouchel Brook:0.939 m Isis River: 0.41 m Wollombi Brook: 0.99 m Bowman River: 0.708 m Kingdon Ponds: 0.05 m Yarrandi Bridge (Dartbrook): Merriwa River: 0.693 m Bulga River: 2.11 m Chichester River: 1.712 m Carrow Brook: 0.869 m Blandford River: 1.088 m Sandy Hollow River: 2.55 m Wingen River: 0.34 m Cressfield River: 0.55 m Gundy River: 0.652 m Lockstock Dam (water level): 155.982 m Moonan Dam: 1.147 m Glenbawn Dam (water level): 258.192 m Liddell Pump Station: 6.367 m.