Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

Newcastle Fortresses

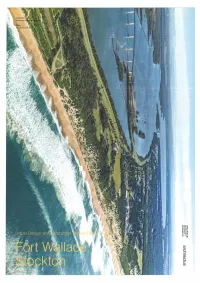

NEWCASTLE FORTRESSES Thanks to Margaret (Marg) Gayler for this article. During World War 2, Newcastle and the surrounding coast between Nelson Bay and Swansea was fortified by Defence forces to protect the east coast of New South Wales against the enemy, in case of attack from the Japanese between 1940 and 1943. There were the established Forts along the coastline, including Fort Tomaree, Fort Wallace (Stockton), Fort Scratchley, Nobbys Head (Newcastle East) and Shepherd’s Hill (Bar Beach) and Fort Redhead. The likes of Fort Tomaree (Nelson Bay), Fort Redhead (Dudley) and combined defence force that operated from Mine Camp (Catherine Hill Bay) came online during the Second World War to also protect our coast and industries like BHP from any attempt to bomb the Industries as they along with other smaller industries in the area helped in the war effort by supplying steel, razor wire, pith hats to our armed forces fighting overseas and here in Australia. With Australia at war overseas the Government of the day during the war years decided it was an urgency to fortify our coast line with not only the Army but also with the help of Navy and Air- Force in several places along the coast. So there was established a line of communication up and down the coast using all three defence forces involved. Starting with Fort Tomaree and working the way down to Fort Redhead adding a brief description of Mine Camp and the role of the RAAF, also mentioning where the Anti Aircraft placements were around Newcastle at the time of WW2. -

National Heritage List Nomination Form for the Coal River Precinct

National Heritage List NOMINATION FORM The National Heritage List is a record of places in the Australian jurisdiction that have outstanding natural, Indigenous or historic heritage values for the nation. These places they are protected by federal law under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Nominating a place for the National Heritage List means identifying its national heritage values on this form and providing supporting evidence. If you need help in filling out this form, contact (02) 6274 2149. Form checklist 1. read the Nomination Notes for advice and tips on answering questions in this form. 2. add attachments and extra papers where indicated (Note: this material will not be returned). 3. provide your details, sign and date the form. Nominated place details Q1. What is the name of the place? The Coal River Precinct, Newcastle (NSW State Heritage Register No.1674) http://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_02_2.cfm?itemid=5053900 and The Convict Lumber Yard (NSW State Heritage Register No.570). http://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_02_2.cfm?itemid=5044978 For the purpose of this nomination „the place‟ including both sites is called the ‘Coal River (Mulubinba) Cultural Landscape’. Give the street address, or, if remote, describe where it is in relation to the nearest Q2. TIP town. Include its area and boundaries. Attach a map with the location and boundaries of the place clearly marked. See the Nomination Notes for map requirements. Q2a. Where is the place? Address/location: The Coal River (Mulubinba) Cultural Landscape is situated at the southern entrance to the Port of Newcastle, New South Wales. -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Executive Summary 5.5 Access and Circulation 33 9.3 Character and Context 78

» JJ --j (J) -j (J) ~ U JJ m (J) (J) o z o 11 --j I m u oJJ oU \ (J) m o o m m< 5 '\ u ~ \ m Z --j \ SPACKMAN MOSSOP~ architectus- Contents MICHAELS Executive summary 5.5 Access and circulation 33 9.3 Character and context 78 Introduction 11 5.6 Landscape 34 9.4 Issues to be resolved through detailed master planning 78 Introduction 13 5.7 Views 35 10 View assessment 80 1.1 The site 13 5.8 Coastal Erosion 36 10.1 Stockton Bridge 80 1.2 Purpose 01 this report 13 5.9 Built form 37 10.2 Fort Wallace Gun Emplacement Number 1 81 1.3 Objectives 01 the master plan 13 5.10 Consolidated constraints and opportunities 39 10.3 Fullerton Street North 82 1.4 The ream 13 10.4 Fullerton Street South 83 The proposal 2 Site context 15 10.5 Fort Scratchley 84 The master plan 43 2.1 Local context 15 10.6 Newcastle Ferry Wharf 85 6.1 The vision 43 2.2 Site analysis 15 10.7 Stockton Beach 86 6.2 Master plan principles 44 2.3 Existing built form 16 6.3 Indicative master plan 46 Conclusion 2.4 Stockton Peninsula History 18 Master plan public domain 51 11 Recommendations 90 2.5 Fort Wallace 19 7.1 Heritage Precinct 54 11.1 Planning controls 90 Strategic planning framework and controls 7.2 Community Park 56 Appendix A 3 Strategic planning context 22 7.3 Landscape Frontage 58 Master plan options 94 3.1 Hunter Regional Plan 22 7.4 Great Streets 60 Master plan options 95 3.2 Port Stephens Planning Strategy (PSPS) 2011 23 Master plan housing mix 66 3.3 Port Stephens Commercial and Industrial Lands Study 23 8.1 Dune apartments 68 Appendix B Local planning context 24 -

Sailing Program 2019-2020

Cruising Yacht Club of Australia 1 New Beach Road, Darling Point, NSW 2027 Telephone: (02) 8292 7800 Email: [email protected] ABN: 28 000 116 423 Race Results: Internet: www.cyca.com.au SAILING PROGRAM 2019-2020 Board of Directors Flag Officers Commodore PAUL BILLINGHAM Vice Commodore NOEL CORNISH Rear-Commodore Rear-Commodore SAM HAYNES JANEY TRELEAVEN Treasurer ARTHUR LANE Directors JUSTIN ATKINSON DAVID JACOBS BRADSHAW KELLETT LEANDER KLOHS Chief Executive Officer EDDIE MOORE Cover Photo: Ichi Ban Photo courtesy of Rolex 1 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Sailing Office & Youth Sailing Academy Sailing Manager – Justine Kirkjian Sailing Administration Supervisor – Tara Blanc-Ramos YSA Administrator – Pam Scrivenor YSA Head Coach – Jordan Reece Marina Tender Driver – 0418 611 672 Tender Hours – Mon-Fri (07:30-16:00), Sat-Sun (08:00-17:00) Acting Operations Manager – Tom Giese – 0407 061 609 Marina Administrator – Max Leonard – 0418 733 933 Sailing Committee Sam Haynes (Chair) Adam Brown David Burt Les Goodridge David Jordan Angelique Kear Bradshaw Kellett Arthur Psaltis Sean Rahilly Matthew van Kretschmar Race Officials Denis Thompson Steve Kidson John Allan Gail Lewis-Bearman Richard Bearman Jennifer Birdsall Brian Carrick Jos Ford Ross Garlan Laure Gaillard-Varlet Paddy Glover Sarla Holmes Tracey Johnstone Aliceson Parker Winona Poon Lyn Ulbricht Contacts CYCA Sailing Office: 02 8292 7870 MV Offshore: 0417 282 172 Marine Rescue Port Jackosn: 02 9719 8609 Sydney Water Police: 02 9320 7499 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE Board -

Sailing Program 2018-2019

SAILINGSAILING PROGRAMPROGRAM 2018-20192015-2016 EMERGENCY GUIDE FOR SYDNEY HARBOUR AMBULANCE – POLICE – FIRE: 000 OR 112 CYCA Reception: (02) 8292 7800 Sailing Office: (02) 8292 7870 MV Offshore: 0417 282 172 Marine Rescue Sydney: (02) 9450 2468 Water Police (02) 9320 7499 RMS /Maritime: 13 12 36 Rose Bay Police Station: (02) 9362 6399 EMERGENCY Manly Ferry Wharf Double Bay Ferry Wharf 77 Bay Street, Double Bay, VHF 16 Belgrave Street and West Esplanade, Manly, 2095 2028 Race Watson’s Bay Ferry Wharf Royal Sydney Yacht 1 Military Road, Watsons Bay, Committee Squadron 2030 33 Peel Street, Kirribilli, 2061 VHF 72 Rose Bay Ferry Wharf Taronga Zoo Ferry Wharf Lyne Park, Nr New South Athol Street, Mosman, 2088 Head Road, Rose Bay, 2029 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia 1 New Beach Road, Darling Point, NSW 2027 Telephone: (02) 8292 7800 Email: [email protected] ABN: 28 000 116 423 Race Results: Internet: www.cyca.com.au SAILING PROGRAM 2018-2019 Board of Directors Flag Officers Commodore PAUL BILLINGHAM Vice Commodore NOEL CORNISH Rear-Commodore Rear-Commodore SAM HAYNES JANEY TRELEAVEN Treasurer ARTHUR LANE Directors JUSTIN ATKINSON DAVID JACOBS BRADSHAW KELLETT LEANDER KLOHS Chief Executive Officer KAREN GREGA Cover Photo: Patrice Photo courtesy of Rolex 1 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Sailing Office & Youth Sailing Academy Sailing Manager – Justine Kirkjian Assistant Sailing Manager – Stephen Craig YSA Supervisor – Pam Scrivenor YSA Coach – Jordan Reece Marina Tender Driver – 0418 611 672 Tender Hours – Mon-Fri (07:30-16:00), Sat-Sun -

The Shoreline, Visiting Places That Once Formed a Crucial Part of Newcastle’S Working Harbour and Maritime Culture

FITZROY STREET FERN STREET YOUNG STREET COWPER STREET COAL ST WILSON STREET DENISON STREET MAITLAND ROAD HUDSON STREET ALBERT STREET DONALD STREET GREENWAY STREET E S U Heavy O H T WALKING Trail 3hrs / 3.2km H CLEARY STREET IG CHURCH STREET L & S Y B B O N LINDSAY STREET O THROSBY STREET Newcastle/Stockton Newcastle Harbour T Ferry RAILWAY STREET SAMDON STREET LINDUS STREET JAMES STREET CAMERON STREET THE 7 Destiny 6 BREAKWALL TUDOR STREET BISHOPGATE STREET Nobbys Beach WHARF ROAD 5 DIXON STREET ELCHO STREET SHORELINE BRIDGE STREET 1 4 MILTON STREET WILLIAM STREET 2 8 MURRAY STREET DENISON STREET EXPLORE NEWCASTLE’SHONEYSUCKLE MARITIME DRIVE AND WORKSHOP PARRY STREET WAY STEEL STREET CENTENARY RD WHARF ROAD ARGYLE ST SURF CULTURE THROUGH A SELF-GUIDED NOBBYS ROAD SCOTT STREET FORT DR MEREWETHER ST SHEPERDS PL WOOD ST 3 BOND ST STEVENSON PLACE VEDA STREET WALKING TOUR OF THE CITY. HUNTER STREET HUNTER STREET ALFRED ST HUNTER STREET BEACH ST SKELTON ST AUCKLAND STREET SHORTLAND ESP CHAUCER STREET KING STREET KING STREET KING STREET STEEL ST EVERTON STREET WARRAH STREET BROWN STREET PARNELL PL DARBY STREET TELFORD STREET PERKINS STREET AVE KING STREET MURRAY HEBBURN STREET OCEAN ST SILSOE STREET UNION STREET CHURCH STREET ZAARA ST DUMARESQ STREET PACIFIC STREET GIBSON STREET AVE BROWN STREET STEEL STREET MORONEY TYRRELL STREET CORONA STREET BOLTON STREET 10 LAMAN STREET 9 KEMP STREET HALL ST DICK ST RAVENSHAW STREET Newcastle Beach QUEEN STREET BULL STREET GLOVERS LN COUNCIL STREET ALEXANDER STREET S W WATT STREET ARNOTT STREET PITT STREET -

OFFICIAL POCKET GUIDE and MAP and GUIDE POCKET OFFICIAL Bars with Spectacular Harbour Views

visitnewcastle.com.au Welcome to Newcastle Discover See & Do Newcastle is one of Australia's oldest and most Despite having inspired Lonely Planet's admiration, interesting cities,offering a blend of new and old Newcastle is yet to be detected by the mass tourism architecture, a rich indigenous history, and one of radar. The seaside city of Newcastle is a great holiday the busiest ports in the world. The land and waters destination with a rich history, quirky arts culture and a of Newcastle are acknowledged as the country of thriving dining and shopping scene. Embark on one of the the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, whose culture many self-guided walking tours or learn how to surf. Spot is celebrated in community events, place naming, local marine life aboard Moonshadow Cruises or Nova signage and artworks. To learn more about Newcastle’s Cruises or get up close to Australian animals at Blackbutt history, take a walk through Newcastle Museum, 5 ways to experience Newcastle like a local Reserve, 182 hectares of natural bushland where you can walk the trails and discover the wildlife. Take a family day Eat & Drink Newcastle Maritime Centre, or visit Fort Scratchley Get your caffeine fix - Over the past few years, Newcastle Historic Site, at its commanding position guarding out to swing and climb like Tarzan at Tree Top Adventure Newcastle has an emerging food scene that makes it has created a coffee culture that gives Melbourne a run for the Hunter River Estuary. Explore Christ Church Park, or for something more relaxing, pack up the picnic an appealing spot to indulge in quality food and wine. -

Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage 1

Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage One HHHiiissstttooorrriiicccaaalll AAAnnnaaalllyyysssiiisss ooofff SSSiiittteeesss aaannnddd RRReeelllaaattteeeddd HHHiiissstttooorrriiicccaaalll aaannnddd CCCuuullltttuuurrraaalll IIInnnfffrrraaassstttrrruuuccctttuuurrreee by Cynthia Hunter, August 2001 Watercolour by unknown artist, c. 1820 Original held at Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales. This illustration encapsulated principal elements of the Coal River Historic Site. The ocean, Nobbys and South Head, the coal seams, the convicts at work quarrying building the breakwater wall and attending to the communication signals, the river, the foreshore, in all, the genesis of a vital commercial city and one of the world’s great ports of the modern industrial age. COAL RIVER HISTORIC SITE 1 Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage 1 Prepared by CCCyyynnnttthhhiiiaaa HHHuuunnnttteeerrr August 2001 CCCooonnnttteeennnttt Provide a Statement of Significance in a National and State context which qualifies the connected cultural significance of the Coal River sites and the Newcastle East precinct ~ Section 1 Identify key sites and secondary sites ~ Section 2 Identify and link areas, sites and relics ~ Section 3 Propose a conceptual framework for an interpretation plan for Stage 3 ~ Section 4 Advise on likelihood and location of the tunnels based on historical research ~ Section 5 COAL RIVER HISTORIC SITE 2 Coal River Time Line 1796 Informal accounts reach Sydney of the reserves of coal at ‘Coal River’. 1797 Lt Shortland and his crew enter Coal River and confirm the coal resources 1801 Formal identification of the great potential of the coal reserves and the river and first and brief attempt to set up a coal mining camp. -

Tea Tree Gully Gem & Mineral Club News

Tea Tree Gully Gem & Mineral Club Inc. (TTGGMC) August Clubrooms: Old Tea Tree Gully School, Dowding Terrace, Tea Tree Gully, SA 5091. Postal Address: Po Box 40, St Agnes, SA 5097. Edition President: Ian Everard. 0417 859 443 Email: [email protected] 2019 Secretary: Claudia Gill. 0419 841 473 Email: [email protected] Treasurer: Russell Fischer. Email: [email protected] Membership Officer: Augie Gray: 0433 571 887 Email: [email protected] Newsletter/Web Site: Mel Jones. 0428 395 179 Email: [email protected] Web Address: https://teatreegullygemandmineralclub.com "Rockzette" Tea Tree Gully Gem & Mineral Club News President’s Report General Interest Club Activities / Fees Meetings Hi All, Pages 2 to 6: TTGGMC 2019 Biennial Exhibition… Club meetings are held on the 1st Thursday of each The Club ran a very successful Biennial Exhibition month except January. (which from now on will just be called a Show) on Committee meetings start at 7 pm. the weekend of 20-21 July. See the full report on General meetings - arrive at 7.30 pm for 8 pm start. page 2. Library We welcomed 4 new members last month – Inta & Librarian - Augie Gray Neal Chambers, Kelly Morrison and Delaney There is a 2-month limit on borrowed items. Lawrance, all of whom have joined the Wednesday Pages 7 to 11: When borrowing from the lending library, fill out the night silversmithing group. Augie’s Agate & Mineral Selections & Mineral Matters… card at the back of the item, then place the card in Tuesdays see up to 14 members attending for the box on the shelf. -

Newcastle Destination Management Plan 2021-2025 V Message from Our Lord Mayor

Newcastle Destination 2021-2025 Management Plan newcastle.nsw.gov.au Acknowledgment City of Newcastle acknowledges that we operate on the grounds of the traditional country of the Awabakal and Worimi peoples. We recognise and respect their cultural heritage, beliefs and continuing relationship with the land and waters, and that they are the proud survivors of more than two hundred years of dispossession. City of Newcastle reiterates its commitment to address disadvantages and attain justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this community. City of Newcastle gratefully acknowledges the contribution made by stakeholders who took part in the consultation phase by attending workshops and meetings, including: Community members; Local businesses; and Regional and State Government Organisations Acronyms AAGR Average Annual Growth Rate LGA Local Government Area ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics LTO Local Toursim Organisation AHA Australian Hotels Association LQ Location Quotient BIA Business Improvement Association MICE Meetings, Incentives, CN City of Newcastle Conferences & Events DMP Destination Management Plan MTB Mountain Bike DNSW Destination NSW NBN National Broadband Network DPIE NSW Government - Department of NBT Nature-Based Tourism Planning, Industry and Environment NTIG Newcastle Tourism Industry Group DSSN Destination Sydney Surrounds North NVS National Visitor Survey EDS Economic Development Strategy PON Port of Newcastle FTE Full Time Equivalent TAA Tourism Accommodation Association HCCDC Hunter & Central Coast