Independent Investigation Into the Collision Between the Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model Of

Creative Documentary Practice: Internalising the Systems Model of Creativity through documentary video and online practice Susan Kerrigan BArts (Comm Studies) (UoN), Grad Cert Practice Tertiary Teaching (UoN) A creative work thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication & Media Arts University of Newcastle, June 2011 Declarations: Declaration 1: I hereby certify that some elements of the creative work Using Fort Scratchley which has been submitted as part of this creative PhD thesis were created in collaboration with another researcher, Kathy Freeman, who worked on the video documentary as the editor. Kathy was working at the Honours level from 2005 to 2006 and I was her Honours Supervisor. Kathy was researching the creative role of the editor, her Honours research was titled Expanding and Contracting the role of the Editor: Investigating the role of the editor in the collaborative and creative procedure of documentary film production (Freeman, 2007). While Kathy’s work dovetailed closely with my own work there was a clear separation of responsibilities and research imperatives, as each of our research topics was focussed on the creative aspects of our different production crew roles. Declaration 2: I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis contains one journal publication and three peer-reviewed published conference papers authored by myself. Kerrigan, S. (2010) Creative Practice Research: Interrogating creativity theories through documentary practice TEXT October 2010. Retrieved 4 November, 2010, Special Issue Number 8, from http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue8/content.htm Kerrigan, S. (2009) Applying creativity theories to a documentary filmmaker’s practice Aspera 2009 - Beyond the Screen: Retrieved from http://www.aspera.org.au/node/40 Kerrigan, S. -

Study-Newcastle-Lonely-Planet.Pdf

Produced by Lonely Planet for Study NT NewcastleDO VIBRAne of Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Cities in Best in Travel 2011 N CREATIVE A LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 L 0 F TOP C O I T TOP E I E N S O 10 CITY I N 10 CITY ! 1 B 1 E 0 S 2 2011 T L I E N V T A R 2011 PLANE LY T’S NE T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T LANET Y P ’S EL TO N P O 1 TOP L 0 F TOP C O I T 10 CITY E I E N S O 10 CITY I N ! 2011 1 B 1 E 0 LAN S P E 2 Y T 2011 T L L ’ I S E N E V T A R N T O O P L F 1 O 0 C E I N T I O E S ! 1 I 1 N 0 B 2 E L S E T V I A N R T E W RE HANI AKBAR st VER I » Age 22 from Saudi Arabia OL » From Saudi Arabia » Studying an International Foundation program What do you think of Newcastle? It’s so beautiful, not big not small, nice. It’s a good place for students who are studying, with a lot of nice people. -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Service Requirements for Third Mate of Ocean Or Near-Coastal Self-Propelled Vessels

Coast Guard, DHS § 11.407 to 50 percent of the total required serv- (i) A minimum of 6 months service as ice. officer in charge of a deck watch on (3) Service on vessels to which STCW ocean self-propelled vessels. applies, whether inland or coastwise, (ii) Service on ocean self-propelled will be credited on a day-for-day basis. vessels as boatswain, able seaman, or (c) A person holding this endorse- quartermaster while holding a certifi- ment may qualify for an STCW en- cate or MMC endorsement as able sea- dorsement, according to § 11.305 of this man, which may be accepted on a two- part. for-one basis to a maximum allowable substitution of six months (12 months § 11.405 Service requirements for chief of experience equals 6 months of cred- mate of ocean or near-coastal self- propelled vessels of unlimited ton- itable service). nage. (b) Service towards an oceans, near- coastal or STCW endorsement will be (a) The minimum service required to credited as follows: qualify an applicant for an endorse- (1) Service on the Great Lakes will be ment as chief mate of ocean or near- credited on a day-for-day basis up to coastal self-propelled vessels of unlim- 100 percent of the total required serv- ited tonnage is 1 year of service as offi- ice. cer in charge of a navigational watch on ocean self-propelled vessels while (2) Service on inland waters, other holding a license or MMC endorsement than Great Lakes, that are navigable as second mate. waters of the United States, will be (b) Service towards an oceans, near- credited on a day-for-day basis for up coastal, or STCW endorsement will be to 50 percent of the total required serv- credited as follows: ice. -

Boatswain's Pipe, the Office of Student Housing Rule Supersedes Those Found in This Publication

Boatswain’s Pipe State University of New York Maritime College “Boatswain’s Pipe” 2013 Edition of the MUG Book Cadet’s Name ________________________________________ Room No. ________________________________________ Key No. ________________________________________ Indoctrination Section ________________________________________ Platoon ________________________________________ Company ________________________________________ Student ID No. ________________________________________ This book was created by the efforts of many Maritime College Cadets, past and present, and is dedicated to help incoming MUGs make their transition to Maritime College and the Regiment of Cadets. "One Hand" Introduction President’s Welcome As the 10th President of the State of New York Maritime College, it is my privilege to welcome you to our nation’s First and Foremost such institution. Steeped in more than 125 years of tradition and a proud history that runs deep and strong, the Maritime College remains a premier institution and a global leader in the field of maritime education and training. We intend to maintain such leadership through a continuing process of strategic improvement of our programs and facilities as well as key engagements and focused outreach to leading industries and academic institutions across a variety of fronts, both nationally and internationally. I can state without reservation that few colleges offer you the combination of such a highly respected academic degree with a strong, hands-on practical component (including Summer Sea Terms onboard our training ship Empire State VI), the opportunity to obtain a Merchant Marine officer’s license, a commission in the armed services if you choose, and the unsurpassed leadership opportunities availavle in the Regiment of Cadets. Indeed few such opportunities in life allow you to grow so rapidly and develop both leadership and technical competencies, which are in high demand in today’s globally integrated and complex environment. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Sailing Program 2019-2020

Cruising Yacht Club of Australia 1 New Beach Road, Darling Point, NSW 2027 Telephone: (02) 8292 7800 Email: [email protected] ABN: 28 000 116 423 Race Results: Internet: www.cyca.com.au SAILING PROGRAM 2019-2020 Board of Directors Flag Officers Commodore PAUL BILLINGHAM Vice Commodore NOEL CORNISH Rear-Commodore Rear-Commodore SAM HAYNES JANEY TRELEAVEN Treasurer ARTHUR LANE Directors JUSTIN ATKINSON DAVID JACOBS BRADSHAW KELLETT LEANDER KLOHS Chief Executive Officer EDDIE MOORE Cover Photo: Ichi Ban Photo courtesy of Rolex 1 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Sailing Office & Youth Sailing Academy Sailing Manager – Justine Kirkjian Sailing Administration Supervisor – Tara Blanc-Ramos YSA Administrator – Pam Scrivenor YSA Head Coach – Jordan Reece Marina Tender Driver – 0418 611 672 Tender Hours – Mon-Fri (07:30-16:00), Sat-Sun (08:00-17:00) Acting Operations Manager – Tom Giese – 0407 061 609 Marina Administrator – Max Leonard – 0418 733 933 Sailing Committee Sam Haynes (Chair) Adam Brown David Burt Les Goodridge David Jordan Angelique Kear Bradshaw Kellett Arthur Psaltis Sean Rahilly Matthew van Kretschmar Race Officials Denis Thompson Steve Kidson John Allan Gail Lewis-Bearman Richard Bearman Jennifer Birdsall Brian Carrick Jos Ford Ross Garlan Laure Gaillard-Varlet Paddy Glover Sarla Holmes Tracey Johnstone Aliceson Parker Winona Poon Lyn Ulbricht Contacts CYCA Sailing Office: 02 8292 7870 MV Offshore: 0417 282 172 Marine Rescue Port Jackosn: 02 9719 8609 Sydney Water Police: 02 9320 7499 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE Board -

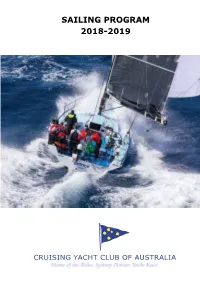

Sailing Program 2018-2019

SAILINGSAILING PROGRAMPROGRAM 2018-20192015-2016 EMERGENCY GUIDE FOR SYDNEY HARBOUR AMBULANCE – POLICE – FIRE: 000 OR 112 CYCA Reception: (02) 8292 7800 Sailing Office: (02) 8292 7870 MV Offshore: 0417 282 172 Marine Rescue Sydney: (02) 9450 2468 Water Police (02) 9320 7499 RMS /Maritime: 13 12 36 Rose Bay Police Station: (02) 9362 6399 EMERGENCY Manly Ferry Wharf Double Bay Ferry Wharf 77 Bay Street, Double Bay, VHF 16 Belgrave Street and West Esplanade, Manly, 2095 2028 Race Watson’s Bay Ferry Wharf Royal Sydney Yacht 1 Military Road, Watsons Bay, Committee Squadron 2030 33 Peel Street, Kirribilli, 2061 VHF 72 Rose Bay Ferry Wharf Taronga Zoo Ferry Wharf Lyne Park, Nr New South Athol Street, Mosman, 2088 Head Road, Rose Bay, 2029 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia 1 New Beach Road, Darling Point, NSW 2027 Telephone: (02) 8292 7800 Email: [email protected] ABN: 28 000 116 423 Race Results: Internet: www.cyca.com.au SAILING PROGRAM 2018-2019 Board of Directors Flag Officers Commodore PAUL BILLINGHAM Vice Commodore NOEL CORNISH Rear-Commodore Rear-Commodore SAM HAYNES JANEY TRELEAVEN Treasurer ARTHUR LANE Directors JUSTIN ATKINSON DAVID JACOBS BRADSHAW KELLETT LEANDER KLOHS Chief Executive Officer KAREN GREGA Cover Photo: Patrice Photo courtesy of Rolex 1 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Sailing Office & Youth Sailing Academy Sailing Manager – Justine Kirkjian Assistant Sailing Manager – Stephen Craig YSA Supervisor – Pam Scrivenor YSA Coach – Jordan Reece Marina Tender Driver – 0418 611 672 Tender Hours – Mon-Fri (07:30-16:00), Sat-Sun -

Sailing Safe Aboard the USNS Able

In This Issue: Productive partnership holds dues line, keeps AMO prosperous — Page 2 STAR Center ‘phase 1’ reopening set for June 1; limited campus access — Page 6 Volume 50, Number 5 May 2020 Sailing safe aboard the USNS Able Members of American Maritime Officers working aboard the USNS Able in April included Captain Phillip Thrift and Third Mate Ryan Trabert. With them is AB Chris Perry. Photos courtesy of Captain Phillip Thrift The USNS Able is operated for Military Sealift Command Working aboard the USNS Able in April were AB Chris Perry, Third Mate Ryan Trabert, Captain Phillip Thrift, MDR by Crowley Liner Services and is manned in all licensed Diamond Anderson and Second Mate Pavel Gorodnichin. positions by AMO. Labor, industry form Wisconsin Domestic Maritime Coalition Thriving Jones Act sector produces $2.2 billion annually for Badger State’s economy Business and labor leaders from around tween U.S. points is reserved for U.S. -built, economy,” said James Weakley, president the Badger State stood up the Wisconsin -owned, -crewed and -documented vessels. of Lake Carriers’ Association. Domestic Maritime Coalition (WIDMAC) as The new coalition will educate state “The state of Wisconsin is a the voice of the domestic maritime industry leaders, media, and policy makers on the leader in the domestic maritime industry, in Wisconsin. The coalition, composed of importance of this vibrant, growing indus- supporting over 9,000 family-wage jobs leading Wisconsin employers and unions, try, fighting for the nearly 10,000 domestic and contributing over $2.2 billion to the launched with an announcement of 41 per- maritime workers in the state, who contin- economy,” said James L. -

The Liberian Shipping Registry

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1999 The Liberian shipping registry : strategies to improve flag state implementation and increase market competitiveness Christian Gbogboda Herbert World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Strategic Management Policy Commons Recommended Citation Herbert, Christian Gbogboda, "The Liberian shipping registry : strategies to improve flag state implementation and increase market competitiveness" (1999). World Maritime University Dissertations. 143. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/143 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden THE LIBERIAN SHIPPING REGISTRY: STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE FLAG STATE IMPLEMENTATION AND INCREASE MARKET COMPETITIVENESS By CHRISTIAN G. HERBERT Liberia A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in MARITIME SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION (MSEP) (Administration) 1999 Ó Copyright Christian G. Herbert, 1999 DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation reflect my own personal view, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. ……………………………………………………… (Signature) ……………………………………………………… (Date) Supervised by: Name: Dr. -

Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage 1

Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage One HHHiiissstttooorrriiicccaaalll AAAnnnaaalllyyysssiiisss ooofff SSSiiittteeesss aaannnddd RRReeelllaaattteeeddd HHHiiissstttooorrriiicccaaalll aaannnddd CCCuuullltttuuurrraaalll IIInnnfffrrraaassstttrrruuuccctttuuurrreee by Cynthia Hunter, August 2001 Watercolour by unknown artist, c. 1820 Original held at Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales. This illustration encapsulated principal elements of the Coal River Historic Site. The ocean, Nobbys and South Head, the coal seams, the convicts at work quarrying building the breakwater wall and attending to the communication signals, the river, the foreshore, in all, the genesis of a vital commercial city and one of the world’s great ports of the modern industrial age. COAL RIVER HISTORIC SITE 1 Coal River Tourism Project Coal River Historic Site Stage 1 Prepared by CCCyyynnnttthhhiiiaaa HHHuuunnnttteeerrr August 2001 CCCooonnnttteeennnttt Provide a Statement of Significance in a National and State context which qualifies the connected cultural significance of the Coal River sites and the Newcastle East precinct ~ Section 1 Identify key sites and secondary sites ~ Section 2 Identify and link areas, sites and relics ~ Section 3 Propose a conceptual framework for an interpretation plan for Stage 3 ~ Section 4 Advise on likelihood and location of the tunnels based on historical research ~ Section 5 COAL RIVER HISTORIC SITE 2 Coal River Time Line 1796 Informal accounts reach Sydney of the reserves of coal at ‘Coal River’. 1797 Lt Shortland and his crew enter Coal River and confirm the coal resources 1801 Formal identification of the great potential of the coal reserves and the river and first and brief attempt to set up a coal mining camp. -

RLM-319 1 Rev 03/18 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. SYLLABUS III

CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. SYLLABUS III. EXAMINATION PROCEDURES IV. THE MULTIPLE-CHOICE EXAMINATION FORMAT: GENERAL ADVICE V. USING ANSWER SHEET VI. SAMPLE QUESTIONS WITH ANSWER KEY VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SUPPLIERS VIII. TABLE OF SI AND IMPERIAL UNITS AND CONVERSION FACTORS IX. MORSE CODE FLASHING LIGHT EXAM X. ENGLISH LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY EXAM I. INTRODUCTION RLM-319 1 Rev 03/18 The Republic of Liberia examination system reflects the provisions of the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping 1978 as amended. Under this system, the examinations consist of multiple-choice questions randomly compiled by computer from a database of some 10,000 questions appropriate for the competency being tested. The answers are graded by computer. Certain training pre-requisites for certification apply. It is recommended that the publication RLM-118, “Requirements for Merchant Marine Personnel Certification,” be consulted to determine which other examinations, certified training or sea service may be required by the Administration before an examination may be taken. The following test centers have been designated for the administration of all officer certificates and/or special qualifications examinations: ALL Exams: LISCR Dulles, Virginia (USA) LISCR New York, New York (USA) LISCR Piraeus, Greece LISCR Hong Kong Ericson & Richards: Mumbai, India PHILCAMSAT: Makati City, Philippines SECOJ: Tokyo, Japan Intercontinental Marine Consultants: Singapore MODU Exams only: Mearns Marine Agency: Stonehaven, Scotland Houston Marine: New Orleans, Louisiana (USA) This booklet has been assembled to familiarize candidates for deck officers' examinations with the examination syllabus and format. It contains information on: a. the examination syllabus; b. examination procedures and passmark requirements; c.