Storyquarterly-52-Digital-Edition.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19-20 Undergraduate Associate

CLASS OF 2020 UNDERGRADUATE ASSOCIATES EAGLETON INSTITUTE OF POLITICS Rutgers University – New Brunswick Wood Lawn, Douglass Campus New Brunswick, NJ eagleton.rutgers.edu EAGLETON UNDERGRADUATE ASSOCIATES PROGRAM The Eagleton Undergraduate Associates Program was established in 1974. During the one and one‐half year certificate program, Associates learn about real‐world politics and government from experienced practitioners. Rutgers students, from all schools and campus locations, are welcome to apply in the fall of their junior year and the selected students begin the following spring. The program is a cooperative educational endeavor between the Eagleton Institute of Politics and the Department of Political Science in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers—New Brunswick. The Undergraduate Associates’ journey at Eagleton begins with the "Practice of Politics" course, where the students examine politics as a choice. Each week, they analyze different political decisions such as the Constitutional Convention, jury verdicts, voting outcomes, budgets, public education systems, legislative actions, campaign strategies, presidential programs, and American policy. Over the summer or fall, Associates complete internships in a variety of offices focused on American politics, government and public policy. Placement locations range from congressional offices and federal agencies in Washington D.C. to state, county and local government positions in New Jersey and New York, along with some of the top political consulting and government affairs firms in the state, among others. The accompanying "Internship Seminar" course in the fall examines the art of leadership in the context of a variety of careers in government and politics. The final course, "Processes of Politics," is taken during the spring semester of senior year and is designed to help students deepen and apply their understanding of politics and governance by focusing on the mechanics of select processes and issues. -

Paul Robeson: Renaissance Man Fought Injustice

Paul Robeson: Renaissance Man Fought Injustice Scholar, athlete was renowned international entertainer and human rights advocate. BY ROYA RAFEI It would have been easier for Paul Robeson to “I am not being tried for whether I am a denounce the Communist party. Communist. I am being tried for fighting for the Throughout the late 1940s and well into the 1950s, the internationally renowned singer was rights of my people, who are still second-class branded a Communist sympathizer, a “Red” citizens in this United States of America.” during the height of the Cold War. His concerts in the U.S. were canceled; record companies —Paul Robeson before the House Un-American Activities dropped him; and the government revoked his Committee, June 12, 1956 passport, denying him the ability to perform abroad. By the time Robeson, a 1919 Rutgers grad- “I am not being tried for whether I am a Paul Leroy Robeson uate and distinguished student, was summoned Communist,” he told the House Un-American is one of the most to appear before the House Un-American Ac- Activities Committee on June 12, 1956. “I am well-known tivities Committee in June 1956, he had already being tried for fighting for the rights of my graduates of lost his reputation, his livelihood, and much of people, who are still second-class citizens in this Rutgers. The future his income. United States of America.” singer, actor, orator, Yet, he refused to back down and say if he Robeson went on to boldly declare to the and civil rights was a member of the Communist party. -

Gogo Vision What's Playing

GOGO VISION WHAT’S PLAYING CATALOG 183 MOVIES (100) TITLE TITLE NEW CONTENT Harriet A Star is Born Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Sherlock Holmes Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 The Big Lebowski Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire The Breakfast Club Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince The Croods Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Those Who Wish Me Dead Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Addams Family, The (2019) Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone An American Pickle Horrible Bosses Batman Begins Horrible Bosses 2 Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice Impractical Jokers: The Movie Bill and Ted Face the Music Invisible Man, The Birds of Prey (And the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) It's Complicated Blinded By The Light Joker Boogie Judas and the Black Messiah Coco Just Mercy Crazy Rich Asians Kajillionaire Crazy, Stupid, Love Let Them All Talk Die Hard Lilo and Stitch Disneys Upside-Down Magic Limbo Doctor Sleep Locked Down E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial Lucy in the Sky Elf Marvel Studios' Black Panther Emma Marvel Studios’ Avengers: Infinity War Finding Dory Marvel’s the Avengers: Age of Ultron Finding Nemo Minions Frozen 2 Mortal Kombat Godzilla v. Kong Mulan Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 My Spy Movies 1 TITLE News of the World The Dark Knight Nobody The Dark Knight Rises Nomadland The Kitchen Office Space The Lego Batman Movie Onward The Lego Movie Photograph, The The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part Queen & Slim -

Gogo Vision What's Playing

GOGO VISION WHAT’S PLAYING CATALOG 179 MOVIES (92) TITLE TITLE NEW CONTENT Finding Nemo Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone Frozen 2 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Good Liar, The Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Harriet Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Impractical Jokers: The Movie Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Invisible Man, The Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 Irresistible Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 It Chapter Two Locked Down It's Complicated Superintelligence Joker The Little Things Just Mercy Ad Astra Kajillionaire Addams Family, The (2019) Let Him Go An American Pickle Let Them All Talk Bill and Ted Face the Music Lilo and Stitch Birds of Prey (And the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) Lucy in the Sky Blinded By The Light Marvel Studios' Black Panther Call of the Wild, The Marvel Studios’ Avengers: Infinity War Charm City Kings Marvel’s the Avengers: Age of Ultron Coco Minions Crazy, Stupid, Love Motherless Brooklyn Die Hard Mulan (Live Action) Disneys Upside-Down Magic My Spy Doctor Sleep Never Rarely Sometimes Always Downhill News of the World E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial Office Space Elf Onward Emma Photograph, The Finding Dory Queen & Slim Movies 1 TITLE Ralph Breaks The Internet: Wreck-It Ralph 2 The Kitchen Ratatouille The Lego Batman Movie Ready or Not The Lego Movie Richard Jewell The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part Rogue One: A Star Wars Story The New Mutants Scoob! The Personal History -

The Observer

The Observer The Official Publication of the Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society http://www.lvaas.org 610-797-3476 http://www.facebook.com/lvaas.astro August 2016 Volume 56 Issue 8 ad ast ra* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * I have to say, I think we had a pretty darn good July picnic this year, despite having to work with a weather situation that was far from ideal. We did play ?chicken? with the thunderstorms. After some fairly vigorous behind-the-scenes debate between members of the Board, I decided that we would take the chance that we might all need to run inside at some point. Sunday (the rain date) would have been a better day, weather-wise, but the problem was that our speaker Jason Kendall was not able to reschedule. And Jason was excellent! We will surely try to have him visit LVAAS again in the future. Hopefully we will find definitive proof that E.T.?s exist sometime soon, so then we can have Mr. Kendall back to eat a little terrestrial crow. He does not believe that it is going to happen. But despite that somewhat-of-a-downer message, his talk was full of energy as well as fascinating science, and he had no problem keeping everyone?s attention when the thunderstorm finally came through, towards the end of his talk. I know a number of people decided not to come when we elected to stay with Saturday, and a few people even assumed that the rain date was in effect when it wasn?t. This is unfortunate and I?m really sorry for the members who were inconvenienced. -

Economics Newsletter Department of Economics Rutgers University Number 46 New Series Summer 2007

Economics Newsletter Department of Economics Rutgers University Number 46 New Series Summer 2007 R UTGERS A Message from the Chairman U NIVERSITY Barry Sopher D EPARTMENT OF E CONOMICS Phone 732-932-7363 Fax 732-932-7416 http://economics.rutgers.edu Construction noise? In spite of tight state and university budgets, the Editors department has been improving its physical plant. The home of much of our Eugene White social and intellectual activity, the Sidney Simon Departmental Library [email protected] received a major facelift. The space on the third floor was renovated this Dorothy Rinaldi summer, from top to bottom, and all the furniture has been replaced. As soon [email protected] as the graduate student computer room, adjoining the library, is completed, the Debra Holman library will be open again, just in time for Fall Semester 2007. The [email protected] department has also embarked on an expansion. Work on a new experimental economics laboratory, located in Scott Hall, has been completed and should be open for experiments at the start of the Fall Semester. This new facility was I NSIDE made possible by a generous donation in the name of a former alumnus. We A Message from the Chair….…….1 anticipate a dedication ceremony for the lab sometime in the fall, pending final Report From the Graduate Director approval for naming the laboratory in memory of the alumnus. ………………………………………2 The new capital campaign for Rutgers is gearing up now, and the Report from the Director of Department of Economics has a number of projects that we anticipate will be Undergraduate Studies…………..4 the focus of fundraising efforts over the next several years. -

Download This PDF File

The JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES VOLUME LIII JUNE 1991 NUMBER 1 LEADERSHIP ON THE BANKS: RUTGERS' PRESIDENTS, 1766-1991 By Thomas J. Frusciano Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, was born out of dissension within the Dutch Reformed Church of America as Queens College in 1766. It struggled for existence throughout much of its infancy, surviving the torments of war and recession during its youth. The college transformed its shape and character several times during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1945, Rutgers reached maturity when it was named the State University of New Jersey. The present configuration of Rutgers as a large public research institution is the result of political, social, and economic conditions that have changed the university over time. The modern Rutgers is also the product of immense dedication bestowed upon it by individuals who as students, alumni, faculty, and administrators have strived to achieve greatness. As the university inaugurates Dr. Francis L. Lawrence as its eighteenth president on March 3, 1991, The Journal takes this special occasion to look back over 225 years of history and accomplishments of those "Leaders on the Banks" who have charted the course that Rutgers has traveled-the past presidents of Rutgers. Chronology of the Presidents of Rutgers 1786--1790 Jacob Rusten Hardenbergh 1791-•1795 William Linn 1795--1810 Ira Condict 1810--1825 John Henry Livingston 1825--1840 Philip Milledoler 1840--1850 Abraham Bruyn Hasbrouck 1850--1862 Theodore Frelinghuysen 1862--1882 William H. Campbell 1882--1890 Merrill Edward Gates 1891--1906 Austin Scott 1906--1924 William Henry Steele Demarest 1925--1930 John Martin Thomas 1930--1931 Philip M. -

Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM

A3 All Local News... NEW or CURRENT SUBSCRIPTIONS FOR $ CALL: 386-752-1293 WEEKS ONLY EMAIL: [email protected] 13 13 (Subscriptions started under this promotion are not eligible for cancellations or refunds. Must be paid in advance.) PRINT AND DIGITAL SATURDAY/SUNDAY, MARCH 28/29, 2020 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $2 WEEKEND EDITION Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM >> TRAVEL SUNDAY + PLUS Staying TALES Don’t think in shape A trip to while the famed anything goes Lafayette 1D due to virus they wait Cemetery Sean of the South Story below SEE 6A LIFE/1D Rebuilding Covid-19 Home ravaged sales church is haven’t now focus missed Deputies say vandal, now in jail, caused up to $100K in damage a beat at Abundant Life on SR 100. Confidence high among agents, brokers as local By TONY BRITT Photos by TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter [email protected] market remains strong. ABOVE: Cagney The man deputies say ran- Tanner, pastor at sacked, vandalized and burglar- By CARL MCKINNEY ized a local church Thursday told Abundant Life, stands [email protected] them he’d been sent home from in the church’s Little Kids building Friday The Covid-19 pandemic work early that day because he continues to stoke fear on caused a disturbance on the job. morning. LEFT: a global level, but the local Deputies say he was drunk or Church members housing market is holding high, and the preacher says the spent hours Friday Acuna firm, according to local real man told him that destroying the morning boarding-up estate industry professionals, church “made him feel good.” broken windows, who say they’re busy as ever The pastor and congregation are praying for but, debris remains thanks to an exodus from the man regardless and are determined not to strewn throughout urban areas hit hard by the let the magnitude of the destruction temper their the area. -

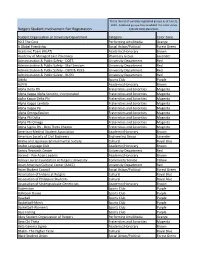

Rutgers Student Involvement Fair Registration Indicate Table Placement

This is the list of currently registered groups as of July 31, 2104. Additonal groups may be added. The Color Zones Rutgers Student Involvement Fair Registration indicate table placement. Student Organization or University Department Category Color Zone 90.3 The Core Performing Arts/Media Orange A Global Friendship Social Action/Political Forest Green Academic Team (RUAT) Academic/Honorary Brown Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Pharmacy Group Lavender Administration & Public Safety - DOTS University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - Mail Services University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - OEM & RUES University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - RUPD University Department Red Aikido Sports Club Purple ALPFA Academic/Honorary Brown Alpha Delta Phi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated Fraternities and Sororities Magenta alpha Kappa Delta Phi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Lambda Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Psi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Omega Epsilon Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Phi Delta Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Phi Omega Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Sigma Phi - Beta Theta Chapter Fraternities and Sororities Magenta American Medical Student Association Academic/Honorary Brown American Society of Civil Engineers Engineering Group Lavender Anime and Japanese Environmental Society Cultural Royal Blue Arabic Language Club Academic/Honorary Brown Aresty Research Center -

Full Historical Sketch

Rutgers University Libraries: Special Collections and University Archives: ASK A LIBRARIAN HOURS & DIRECTIONS SEARCH WEBSITE SITE INDEX MY ACCOUNT LIBRARIES HOME Libraries & Collections: Special Collections and University Archives: University SEARCH IRIS AND Archives: OTHER CATALOGS A Historical Sketch of Rutgers University FIND ARTICLES FIND ARTICLES WITH by Thomas J. Frusciano, University Archivist SEARCHLIGHT FIND RESERVES ● The Founding of Queen's College RESEARCH RESOURCES ● From Queen's to Rutgers College ● The Transformation of a College CONNECT FROM OFF- CAMPUS ● Rutgers and the State of New Jersey ● The Depression and Word War II HOW DO I...? ● Post-War Expansion and the State University REFWORKS ● The Research University SEARCHPATH LIBRARY INSTRUCTION The Founding of Queen's College BORROWING DELIVERY AND Queen's College, founded in 1766 as the eighth oldest college in the United States, INTERLIBRARY LOAN owes its existence to a group of Dutch Reformed clerics who fought to secure REFERENCE independence from the church in the Netherlands. The immediate issue of concern was the lack of authority within the American churches to ordain and educate ministers in FACULTY SERVICES the colonies. During the 1730's, a revitalization of religious fervor during the Great ABOUT THE LIBRARIES Awakening created a proliferation of churches for which existed a severe shortage of NEWS AND EVENTS ministers available to preach the gospel. Those who aspired to the pulpit were required to travel to Amsterdam for their training, a long and arduous journey. ALUMNI LIBRARY In 1747, a group of Dutch ministers created the Coetus to gain autonomy in ecclesiastical affairs. The Classis of Amsterdam reluctantly approved the Coetus but severely limited its authority to the examination and ordination of ministers under RETURN TO RUTGERS special circumstances; ultimate authority in church government remained in the HOME PAGE Netherlands. -

The Legacy of Paul Robeson

The Legacy of Paul Robeson One hundred years ago, in 1919, Paul Robeson graduated from Rutgers College, New Brunswick at the top of his class. Academically, he was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Rutgers Cap and Skull Honor Society, and he was named valedictorian of his class. He received an unprecedented twelve major athletic letters in multiple sports, and later played for the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers while attending law school at Columbia. Robeson was the 3rd African American in history to graduate from Rutgers, and through his ongoing work he became one of the greatest Americans of the 20th century. He was an exceptional athlete, lawyer, actor, singer, cultural scholar, author, and political activist, advocating for the civil rights of people around the world. Enduring unjust strife and inequality and using it for positive social change and justice was a true testament to his integrity, character and spirit. In the mid-1920s, after a short legal career, he returned to his love of public speaking in American theater, and through the 1930s, he was a widely acclaimed actor and singer. His “Othello” was the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history, running for nearly three hundred performances. With songs such as his trademark “Ol’ Man River,” he became one of the most popular concert singers of his time. While his fame grew in the United States, he became equally well-loved internationally. He spoke fifteen languages, and performed benefits throughout the world for causes of social justice. More than any other performer of his time, he believed that the famous have a responsibility to fight for justice and peace. -

Juveniles Destructive 1?5 Cliffwood Beach Housewives Aroused By

Juveniles Destructive $7590 For Building ' 1?5 Cliffwood Beach At Wafer Works Siie Householder Demands Middlesex Rd. Structure Protection; Special To House Pump, Used Officers Are Named -Foi Recreation, Voting Juvpr,iii> delinquency was de- clared--!©- be-- running wild in; -Member-National Ed itorial'Association^=^New^Jersey~Fress~Association — IVlonnnouth County Press Association An ordinance to appropriate Ciiffwccc" Bench by n liousehol- 57500 and bond the borough for $6500 of it was introduced at; dcr, ]>5.-s. Raymond Ryno, 231 87th YEAR — 13th WEEK MATAWAN, N. J., THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1955 Single Copy Seven Cents Broocifi&e Ave.. who appeared council meeting: so a building before ti.e Mntawan Township to house pumps for the new wa- (.^tnmittee yesterday. ter works and provide a voting Alarm, But No Fire! Officer Sent On Raid and recreational center at the Mrs. KyiiO claimed that for Housewives Aroused Recreation Group 'owner Alice Dawe property on the li:\v months she had been A brief, but exciting, few Patrolman Robert McGow- moments occurred at the close iii, Malawan Police, receiv- Middlesex Rd. can be erected. a rctSrleni. of Cliffwood Beach, The borough bought the land the if.nct' in iront- of her home of the Union Beach council By Marlboro Roads Planning Projects ed instructions from Chief meeting Thursday night when John J. Flood yesterday aft. rom Mr. Dawe when the new and ;-i)c houte next door had water works was first project- been twii down by vnndnls Ihe four Union Beach Fire Gravel Just "Red Dirt" To Meet With Other ernoon to be ready for a raid Companies were called out to be staged that night at ed.