Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19-20 Undergraduate Associate

CLASS OF 2020 UNDERGRADUATE ASSOCIATES EAGLETON INSTITUTE OF POLITICS Rutgers University – New Brunswick Wood Lawn, Douglass Campus New Brunswick, NJ eagleton.rutgers.edu EAGLETON UNDERGRADUATE ASSOCIATES PROGRAM The Eagleton Undergraduate Associates Program was established in 1974. During the one and one‐half year certificate program, Associates learn about real‐world politics and government from experienced practitioners. Rutgers students, from all schools and campus locations, are welcome to apply in the fall of their junior year and the selected students begin the following spring. The program is a cooperative educational endeavor between the Eagleton Institute of Politics and the Department of Political Science in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers—New Brunswick. The Undergraduate Associates’ journey at Eagleton begins with the "Practice of Politics" course, where the students examine politics as a choice. Each week, they analyze different political decisions such as the Constitutional Convention, jury verdicts, voting outcomes, budgets, public education systems, legislative actions, campaign strategies, presidential programs, and American policy. Over the summer or fall, Associates complete internships in a variety of offices focused on American politics, government and public policy. Placement locations range from congressional offices and federal agencies in Washington D.C. to state, county and local government positions in New Jersey and New York, along with some of the top political consulting and government affairs firms in the state, among others. The accompanying "Internship Seminar" course in the fall examines the art of leadership in the context of a variety of careers in government and politics. The final course, "Processes of Politics," is taken during the spring semester of senior year and is designed to help students deepen and apply their understanding of politics and governance by focusing on the mechanics of select processes and issues. -

Paul Robeson: Renaissance Man Fought Injustice

Paul Robeson: Renaissance Man Fought Injustice Scholar, athlete was renowned international entertainer and human rights advocate. BY ROYA RAFEI It would have been easier for Paul Robeson to “I am not being tried for whether I am a denounce the Communist party. Communist. I am being tried for fighting for the Throughout the late 1940s and well into the 1950s, the internationally renowned singer was rights of my people, who are still second-class branded a Communist sympathizer, a “Red” citizens in this United States of America.” during the height of the Cold War. His concerts in the U.S. were canceled; record companies —Paul Robeson before the House Un-American Activities dropped him; and the government revoked his Committee, June 12, 1956 passport, denying him the ability to perform abroad. By the time Robeson, a 1919 Rutgers grad- “I am not being tried for whether I am a Paul Leroy Robeson uate and distinguished student, was summoned Communist,” he told the House Un-American is one of the most to appear before the House Un-American Ac- Activities Committee on June 12, 1956. “I am well-known tivities Committee in June 1956, he had already being tried for fighting for the rights of my graduates of lost his reputation, his livelihood, and much of people, who are still second-class citizens in this Rutgers. The future his income. United States of America.” singer, actor, orator, Yet, he refused to back down and say if he Robeson went on to boldly declare to the and civil rights was a member of the Communist party. -

Catalogue of the Officers and Alumni of Rutgers College

* o * ^^ •^^^^- ^^-9^- A <i " c ^ <^ - « O .^1 * "^ ^ "^ • Ellis'* -^^ "^ -vMW* ^ • * ^ ^^ > ->^ O^ ' o N o . .v^ .>^«fiv.. ^^^^^^^ _.^y^..^ ^^ -*v^^ ^'\°mf-\^^'\ \^° /\. l^^.-" ,-^^\ ^^: -ov- : ^^--^ .-^^^ \ -^ «7 ^^ =! ' -^^ "'T^s- ,**^ .'i^ %"'*-< ,*^ .0 : "SOL JUSTITI/E ET OCCIDENTEM ILLUSTRA." CATALOGUE ^^^^ OFFICERS AND ALUMNI RUTGEES COLLEGE (ORIGINALLY QUEEN'S COLLEGE) IlSr NEW BRUJSrSWICK, N. J., 1770 TO 1885. coup\\.to ax \R\l\nG> S-^ROUG upsoh. k.\a., C\.NSS OP \88\, UBR^P,\^H 0? THP. COLLtGit. TRENTON, N. J. John L. Murphy, Printer. 1885. w <cr <<«^ U]) ^-] ?i 4i6o?' ABBREVIATIONS L. S. Law School. M. Medical Department. M. C. Medical College. N. B. New Brunswick, N. J. Surgeons. P. and S. Physicians and America. R. C. A. Reformed Church in R. D. Reformed, Dutch. S.T.P. Professor of Sacred Theology. U. P. United Presbyterian. U. S. N. United States Navy. w. c. Without charge. NOTES. the decease of the person. 1. The asterisk (*) indicates indicates that the address has not been 2. The interrogation (?) verified. conferred by the College, which has 3. The list of Honorary Degrees omitted from usually appeared in this series of Catalogues, is has not been this edition, as the necessary correspondence this pamphlet. completed at the time set for the publication of COMPILER'S NOTICE. respecting every After diligent efforts to secure full information knowledge in many name in this Catalogue, the compiler finds his calls upon every one inter- cases still imperfect. He most earnestly correcting any errors, by ested, to aid in completing the record, and in the Librarian sending specific notice of the same, at an early day, to Catalogue may be as of the College, so that the next issue of the accurate as possible. -

James E. Boasberg - Wikipedia

12/30/2019 James E. Boasberg - Wikipedia James E. Boasberg James Emanuel "Jeb" Boasberg (born February 20, 1963)[2] is a James E. Boasberg United States District Judge on the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, also serving as a Judge on the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court; and former associate judge on the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. Contents Early life and education Clerkship and legal career Judicial service Osama Bin Laden photos Registered tax return preparer regulations Appointment to United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Hillary Clinton emails Presiding Judge of the United Trump tax returns States Foreign Intelligence Medicaid work rules Surveillance Court Incumbent Personal life Assumed office See also January 1, 2020 References Appointed by John Roberts External links Preceded by Rosemary M. Collyer Judge of the United States Early life and education Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Boasberg was born in San Francisco, California in 1963,[3] to Sarah Incumbent Margaret (Szold) and Emanuel Boasberg III.[4][5] The family moved to Washington, D.C. when Boasberg's father accepted a position in Sargent Assumed office Shriver's Office of Economic Opportunity, a Great Society agency May 18, 2014 responsible for implementing and administering many of Lyndon B. Appointed by John Roberts [6][7] Johnson's War on Poverty programs. Boasberg received a Bachelor Preceded by Reggie Walton of Arts from Yale University in 1985, where he was a member of Skull Judge of the United States District [8] and Bones, and a Master of Studies the following year from Oxford Court for the District of Columbia [9] University. -

The Observer

The Observer The Official Publication of the Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society http://www.lvaas.org 610-797-3476 http://www.facebook.com/lvaas.astro August 2016 Volume 56 Issue 8 ad ast ra* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * I have to say, I think we had a pretty darn good July picnic this year, despite having to work with a weather situation that was far from ideal. We did play ?chicken? with the thunderstorms. After some fairly vigorous behind-the-scenes debate between members of the Board, I decided that we would take the chance that we might all need to run inside at some point. Sunday (the rain date) would have been a better day, weather-wise, but the problem was that our speaker Jason Kendall was not able to reschedule. And Jason was excellent! We will surely try to have him visit LVAAS again in the future. Hopefully we will find definitive proof that E.T.?s exist sometime soon, so then we can have Mr. Kendall back to eat a little terrestrial crow. He does not believe that it is going to happen. But despite that somewhat-of-a-downer message, his talk was full of energy as well as fascinating science, and he had no problem keeping everyone?s attention when the thunderstorm finally came through, towards the end of his talk. I know a number of people decided not to come when we elected to stay with Saturday, and a few people even assumed that the rain date was in effect when it wasn?t. This is unfortunate and I?m really sorry for the members who were inconvenienced. -

Economics Newsletter Department of Economics Rutgers University Number 46 New Series Summer 2007

Economics Newsletter Department of Economics Rutgers University Number 46 New Series Summer 2007 R UTGERS A Message from the Chairman U NIVERSITY Barry Sopher D EPARTMENT OF E CONOMICS Phone 732-932-7363 Fax 732-932-7416 http://economics.rutgers.edu Construction noise? In spite of tight state and university budgets, the Editors department has been improving its physical plant. The home of much of our Eugene White social and intellectual activity, the Sidney Simon Departmental Library [email protected] received a major facelift. The space on the third floor was renovated this Dorothy Rinaldi summer, from top to bottom, and all the furniture has been replaced. As soon [email protected] as the graduate student computer room, adjoining the library, is completed, the Debra Holman library will be open again, just in time for Fall Semester 2007. The [email protected] department has also embarked on an expansion. Work on a new experimental economics laboratory, located in Scott Hall, has been completed and should be open for experiments at the start of the Fall Semester. This new facility was I NSIDE made possible by a generous donation in the name of a former alumnus. We A Message from the Chair….…….1 anticipate a dedication ceremony for the lab sometime in the fall, pending final Report From the Graduate Director approval for naming the laboratory in memory of the alumnus. ………………………………………2 The new capital campaign for Rutgers is gearing up now, and the Report from the Director of Department of Economics has a number of projects that we anticipate will be Undergraduate Studies…………..4 the focus of fundraising efforts over the next several years. -

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey FACT BOOK 2006

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey FACT BOOK 2006 - 2007 Office of Institutional Research and Academic Planning Geology Hall, First Floor Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 85 Somerset Street New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-1281 (732) 932 - 7305 http://oirap.rutgers.edu Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey ii Table of Contents Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Page Overview ix Our Vision x Programs - Degree and Program Offerings xi University Quick Facts xii-xiii Almanac of Historical Facts xiv Rutgers' Presidents, 1766 - 1991 xv STUDENTS 1. Admissions Applied, Admitted, and Enrolled by Campus 1 Applied, Admitted, and Enrolled by Gender and Race/Ethnicity Camden Campus, First-Year Undergraduate Students 2 Newark Campus, First-Year Undergraduate Students 3 New Brunswick Campus, First-Year Undergraduate Students 4 Camden Campus, Transfer Undergraduate Students 5 Newark Campus, Transfer Undergraduate Students 6 New Brunswick Campus, Transfer Undergraduate Students 7 2. Enrollment Headcount Enrollment by Campus, Full-Time/Part-Time Status, and Academic Level 9 Total University Enrollment 10 Headcount Enrollment by Full-Time/Part-Time Status for Total University 11 Headcount Enrollment by Academic Level, Campus, and Full-Time/Part-Time Status 12 Full-Time Equivalent Enrollment by Academic Level and Campus 13 Full-Time Equivalent Enrollment by Campus, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity Undergraduate Students 14 Graduate/Professional Students 15 Total Students 16 Full-Time Equivalent Enrollment by Campus, Gender, and Age Undergraduate -

Rutgers Student Involvement Fair Registration Indicate Table Placement

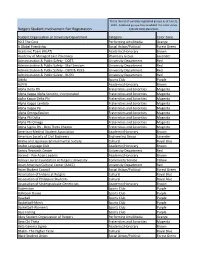

This is the list of currently registered groups as of July 31, 2104. Additonal groups may be added. The Color Zones Rutgers Student Involvement Fair Registration indicate table placement. Student Organization or University Department Category Color Zone 90.3 The Core Performing Arts/Media Orange A Global Friendship Social Action/Political Forest Green Academic Team (RUAT) Academic/Honorary Brown Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Pharmacy Group Lavender Administration & Public Safety - DOTS University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - Mail Services University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - OEM & RUES University Department Red Administration & Public Safety - RUPD University Department Red Aikido Sports Club Purple ALPFA Academic/Honorary Brown Alpha Delta Phi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated Fraternities and Sororities Magenta alpha Kappa Delta Phi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Lambda Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Kappa Psi Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Omega Epsilon Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Phi Delta Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Phi Omega Fraternities and Sororities Magenta Alpha Sigma Phi - Beta Theta Chapter Fraternities and Sororities Magenta American Medical Student Association Academic/Honorary Brown American Society of Civil Engineers Engineering Group Lavender Anime and Japanese Environmental Society Cultural Royal Blue Arabic Language Club Academic/Honorary Brown Aresty Research Center -

University Fact Book

UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK Office of Institutional Research and Academic Planning Geology Hall, First Floor Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 85 Somerset Street New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901‐1281 (848) 932‐7305 http://oirap.rutgers.edu Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Overview Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is the premier public university of New Jersey and one of the oldest and most highly regarded institutions of higher education in the nation. With more than 68,000 students and more than 22,000 faculty and staff on its three major campuses in New Brunswick, Newark, and Camden, Rutgers is a vibrant academic community committed to the highest standards of teaching, research, and service. With 31 schools and colleges, Rutgers offers over 100 undergraduate majors and more than 200 graduate and professional degree programs. The university graduates more than 16,000 students each year and has nearly 486,000 living alumni residing in all 50 state, in the District of Columbia, in six U.S. territories and on six continents. While these numbers are impressive, they do not capture the magnitude of Rutgers’ dramatic recent transformation. Founded over 250 years ago in 1766, Rutgers is distinguished as one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the country. Rutgers is one of the nation’s 74 land-grant institutions, in the company of other land-grants such as Cornell, MIT, Ohio State, and Penn State. The Morrill Act of 1862 designated these institutions to serve the states and their citizens by disseminating practical knowledge developed at key institutions of higher learning. -

Full Historical Sketch

Rutgers University Libraries: Special Collections and University Archives: ASK A LIBRARIAN HOURS & DIRECTIONS SEARCH WEBSITE SITE INDEX MY ACCOUNT LIBRARIES HOME Libraries & Collections: Special Collections and University Archives: University SEARCH IRIS AND Archives: OTHER CATALOGS A Historical Sketch of Rutgers University FIND ARTICLES FIND ARTICLES WITH by Thomas J. Frusciano, University Archivist SEARCHLIGHT FIND RESERVES ● The Founding of Queen's College RESEARCH RESOURCES ● From Queen's to Rutgers College ● The Transformation of a College CONNECT FROM OFF- CAMPUS ● Rutgers and the State of New Jersey ● The Depression and Word War II HOW DO I...? ● Post-War Expansion and the State University REFWORKS ● The Research University SEARCHPATH LIBRARY INSTRUCTION The Founding of Queen's College BORROWING DELIVERY AND Queen's College, founded in 1766 as the eighth oldest college in the United States, INTERLIBRARY LOAN owes its existence to a group of Dutch Reformed clerics who fought to secure REFERENCE independence from the church in the Netherlands. The immediate issue of concern was the lack of authority within the American churches to ordain and educate ministers in FACULTY SERVICES the colonies. During the 1730's, a revitalization of religious fervor during the Great ABOUT THE LIBRARIES Awakening created a proliferation of churches for which existed a severe shortage of NEWS AND EVENTS ministers available to preach the gospel. Those who aspired to the pulpit were required to travel to Amsterdam for their training, a long and arduous journey. ALUMNI LIBRARY In 1747, a group of Dutch ministers created the Coetus to gain autonomy in ecclesiastical affairs. The Classis of Amsterdam reluctantly approved the Coetus but severely limited its authority to the examination and ordination of ministers under RETURN TO RUTGERS special circumstances; ultimate authority in church government remained in the HOME PAGE Netherlands. -

The Legacy of Paul Robeson

The Legacy of Paul Robeson One hundred years ago, in 1919, Paul Robeson graduated from Rutgers College, New Brunswick at the top of his class. Academically, he was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Rutgers Cap and Skull Honor Society, and he was named valedictorian of his class. He received an unprecedented twelve major athletic letters in multiple sports, and later played for the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers while attending law school at Columbia. Robeson was the 3rd African American in history to graduate from Rutgers, and through his ongoing work he became one of the greatest Americans of the 20th century. He was an exceptional athlete, lawyer, actor, singer, cultural scholar, author, and political activist, advocating for the civil rights of people around the world. Enduring unjust strife and inequality and using it for positive social change and justice was a true testament to his integrity, character and spirit. In the mid-1920s, after a short legal career, he returned to his love of public speaking in American theater, and through the 1930s, he was a widely acclaimed actor and singer. His “Othello” was the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history, running for nearly three hundred performances. With songs such as his trademark “Ol’ Man River,” he became one of the most popular concert singers of his time. While his fame grew in the United States, he became equally well-loved internationally. He spoke fifteen languages, and performed benefits throughout the world for causes of social justice. More than any other performer of his time, he believed that the famous have a responsibility to fight for justice and peace. -

History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ "The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ

"The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ "The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ by the Rev. Dr. J David Muyskens published by the Consistory 1991 FOREWORD The last time someone compiled a history of First Reformed Church was when Dr. Richard H. Steele presented his Historical Discourse Delivered at the Celebration of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the First Reformed Dutch Church, New Brunswick, N.J. That was on October 1, 1867. The discourse was published by the Consistory. There are still a few copies in existence of that volume. But it seems time for an update. My work on writing the history of First Church began with a series of Wednesday evening lectures during lent some years ago. My research continued since then as I read consistory minutes, old newsletters, and talked to some of the older members of the congregation compiling the story that follows on these pages. It is a story in which the hand of God is evident. It is the story of dedicated people who gave much in the service of Christ. It is the story of a church which has played a central role in the life of its community. For a time it was known as ''the Town Clock Church' as its tower has housed the town clock of the city of New Brunswick for one hundred and sixty years. Its earliest names reflected the fact that it was a church organized to serve its community. The names expressed the geographic location of its congregation.