A Comparative Linguistic and Cultural Study of Lexical Influences on Konkani 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pray for India Pray for Rulers of Our Nation Praise God for The

Pray for India “I have posted watchmen on your walls, Jerusalem; they will never be silent day or night. You who call on the Lord, give yourselves no rest, and give him no rest till he establishes Jerusalem and makes her the praise of the earth” (Isaiah 62:6-7) Population : 127.08 crores Christians 6 crores approx. (More than 5% - assumed) States : 29 Union Territories : 7 Lok Sabha & Rajya Sabha Members : 780 MLA’s : 4,120 Approx. 30% of them have criminal backgrounds Villages : 7 lakh approx. (No Churches in 5 lakh villages) Towns : 31 (More than 10 lakh population) 400 approx. (More than 1 lakh population) People Groups : 4,692 Languages : 460 (Official languages - 22) Living in slums : 6,50,00,000 approx. Pray for Rulers of our Nation President of India : Mr. Ram Nath Kovind Prime Minister : Mr. Narendra Modi Lok Sabha Sepeaker : Mrs. Sumitra Mahajan Central Cabinet, Ministers of state, Deputy ministers, Opposition leaders and members to serve with uprightness. Governors of the states, Chief Ministers, Assembly leaders, Ministers, Members of Legislative Assembly, Leaders and Members of the Corporations, Municipalities and Panchayats to serve truthfully. General of Army, Admirals of Navy and Air Marshals of Air force. Planning Commission Chairman and Secretaries. Chief Secretaries, Secretaries, IAS, IPS, IFS Officials. District collectors, Tahsildars, Officials and Staff of the departments of Revenue, Education, Public works, Health, Commerce, Agriculture, Housing, Industry, Electricity, Judiciary, etc. Heads, Officials and Staff of Private sectors and Industries. The progress of farmers, businessmen, fisher folks, self-employed, weavers, construction workers, computer operators, sanitary workers, road workers, etc. -

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Journal of Social and Economic Development Vol. 4 No.2 July-December 2002 Spatial Poverty Traps in Rural India: An Exploratory Analysis of the Nature of the Causes Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala Economic and Environmental Status of Drinking Water Provision in Rural India The Politics of Minority Languages: Some Reflections on the Maithili Language Movement Primary Education and Language in Goa: Colonial Legacy and Post-Colonial Conflicts Inequality and Relative Poverty Book Reviews INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE BANGALORE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (Published biannually in January and July) Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore–560 072, India Editor: M. Govinda Rao Managing Editor: G. K. Karanth Associate Editor: Anil Mascarenhas Editorial Advisory Board Isher Judge Ahluwalia (Delhi) J. B. Opschoor (The Hague) Abdul Aziz (Bangalore) Narendar Pani (Bangalore) P. R. Brahmananda (Bangalore) B. Surendra Rao (Mangalore) Simon R. Charsley (Glasgow) V. M. Rao (Bangalore) Dipankar Gupta (Delhi) U. Sankar (Chennai) G. Haragopal (Hyderabad) A. S. Seetharamu (Bangalore) Yujiro Hayami (Tokyo) Gita Sen (Bangalore) James Manor (Brighton) K. K. Subrahmanian Joan Mencher (New York) (Thiruvananthapuram) M. R. Narayana (Bangalore) A. Vaidyanathan (Thiruvananthapuram) DTP: B. Akila Aims and Scope The Journal provides a forum for in-depth analysis of problems of social, economic, political, institutional, cultural and environmental transformation taking place in the world today, particularly in developing countries. It welcomes articles with rigorous reasoning, supported by proper documentation. Articles, including field-based ones, are expected to have a theoretical and/or historical perspective. The Journal would particularly encourage inter-disciplinary articles that are accessible to a wider group of social scientists and policy makers, in addition to articles specific to particular social sciences. -

Page 1 of 17 List of Literary Associations Recognized by Sahitya

List of Literary Associations recognized by Sahitya Akademi (Updated on 10 May 2021) ASSAMESE 1) The General Secretary Asam Sahitya Sabha Chandrakanta Handique Bhavan, Jorhat 785 001 Assam 2) The President Sadou Asom Lekhika Samaroh Samity Sahid Chariali, Padum Pukhuripar, Tezpur – 784 001, Assam BENGALI 1) The Secretary Rabindra Bharati Society 5, Dwarakanath Tagore Lane Kolkata-700 007 Bengal 2) The Secretary Bangiya Sahitya Parishad 243/1, Acharya Parafullachandra Road Kolkata-700 006 Bengal BODO 1) The General Secretary Bodo Sahitya Sabha R.N. Brahma Hall Kokrajhar BATD-783 370 Assam 2) The President Bodo Writers’ Academy H.O. & P.O. Kajalgaon Dist. Chirang : Bodoland Assam-783385 Page 1 of 17 DOGRI 1) The General Secretary Dogri Sanstha (Regd.) Dogri Bhawan Karan Nagar Jammu Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir 2) The Secretary Kavi Dattu Sahitya Sansthan (Vill. & P.O. Bhadoo, Tehsil: Bilawar Dist: Kathua, Jammu Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir 3) The General Secretary Dogri Sahitya Sabha, Marh P.O. Halqa Dist: Jammu – 181206 Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir 4) The General Secretary Duggar Manch 124, Dogra Hall Jammu-180 001 Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir 5) The General Secretary Nami Dogri Sanstha 22-D, Lane No. 1 Tavi Vihar Sidra, Jammu-181 019 Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir ENGLISH-No Literary Association GUJARATI 1) The Secretary Gujarati Sahitya Parishad Govardhan Bhavan, Gujarati Sahitya Parishad Marg, River Front, Ashram Road, P.B. No.4060, Ahmedabad-380 009 Page 2 of 17 2) The Secretary Gujarat Vidya Sabha H.K. Arts College Ashram Road Near Times of India Ahmedabad-380 009 3) The Secretary Gujarat Sahitya Sabha Room No. -

Hands-On Experience

Hands-on Experience Competitions, Course Projects, Original Ideas & Innovation Cell Strictly Private & Confidential Competitions . Competitions Competitions Original ideas Original ideas Course projects Technology explorations Technology explorations Founded in Feb 2007 Technology platform creating indigenous Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) & Autopilots Leadership team Rahul Ashish Ankit Vipul Ankit Mehta Co-founder & CEO B.Tech & M.Tech (DD) Mech. Engg., IIT Bombay, 2005 Ashish Bhat Co-founder & CTO B.Tech, Elec. Engg., IIT Bombay, 2006 Rahul Singh Co-founder & CTO B.Tech, Mech. Engg., IIT Bombay, 2006 Vipul Joshi Co-promoter & COO MBA, Univ. of Business & Finance, Switzerland, 2008 Strictly Private & Confidential Our journey 10gms First Quadrotor UAV explorations 2005 ROBOCON 2005, Beijing, China Autopilot UAV Avionics projects for Aero. Dept., IITB 2007 With IITB in MAV’2008, DOD, USA & Indian Army Shared 1st prize with MIT, USA 2008 World’s smallest and lightest proprietary Autopilot 2009 Featured in the movie First indigenous UAV in India “3 idiots” Huge demand from DRDO and security forces First UAV sale 2010 MOU and Rate Contract with DRDO Launched NETRA UAV 2011 Upgraded NETRA Extensive Demos 2012 Developed Fixed Wing UAV Won India’s first UAV tender Volunteered in Uttarakhand 2013 High endurance and range UAVs Services Business 2014 Strictly Private & Confidential UAV canvas Development focus MALE/HALE Current focus Mini Tactical Altitude/ Range Altitude/ Small Micro Insect Small Tactical Micro Size/ Endurance Strictly Private -

Pronunciation Rules in Portuguese Regional Speech (PORT REG) for Coarticulation Process

Pronunciation Rules in Portuguese Regional Speech (PORT REG) for Coarticulation Process Sara Candeias1 and Jorge Morais Barbosa 2 1 Instituto de Telecomunicações, Department of Computers and Electrical Engineering, University of Coimbra, PORTUGAL 2 Departement of Portuguese Language, Faculty of Letters, University of Coimbra, PORTUGAL [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. This paper describes one aspect of an ongoing work to incorporate pronunciation variability in the Portuguese (PORT) speech system. This work focuses on the linguistic rules to improve the grapheme-(multi)phone transcription algorithm that will be implemented. Portuguese ‘Beira Interior’ regional speech (PORT-BI REG) is considered to be in the realm of coarticulation (post-lexical) phenomena. A set of linguistic rules for most of the common vowel transformation in an utterance (vocalic segments at both the left and right edges of the word) is presented. The analysis focuses on the distinctive features that originate vowel sound challenges in connected speech. The results are interesting from the point of view of setting up models to reconstruct a grapheme-phone transcription algorithm for Portuguese multi-pronunciation speech systems. We propose that the linguistic documentation of Portuguese minority speech can be an optimal start for Portuguese speech system development process, too. Keywords: Text-to-Speech; coarticulation (phonology); structural analysis (linguistic features); pronunciation instruction (phonetic). 1 Introduction Several frameworks have been proposed for the grapheme-to-phone transcription module for Portuguese language, such as [2, 3, 12]. However, the problem with the Portuguese regional speech under development is the shortage of speech and text corpora. This is one of the reasons why their linguistic structure has been very poorly investigated, especially at linguistic levels such as phonetics. -

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay

FEE STRUCTURE Category Fees applicable Course work fees / Project work fees under MoU category No fees charged Course work fees under non MoU category USD 400 per course per semester Project fees under Non - MoU category USD 150 per month Hostel charges USD 400 per semester for students doing course work USD 100 per month for students doing project work INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY BOMBAY (Additional days of stay will be charged on per day basis as per prevailing hostel rules & will be collected by the Hostel) Administration fees USD 250 per semester for students doing course work. INFORMATION FOR USD 250 one time on joining for students doing project work. Students doing both course work and project work will pay only USD 250. VISITING STUDENTS (Optional) Library deposit Mess advance Refundable Mess Advance Rs 10,000 Rs 27,000 Rs 2,000 (These are approximate amounts. The actual amounts will be communicated to the students by the respective hostels at the time of joining). # All fees are subject to revision from time to time. A semester is considered to be a period of 4 months or less MODE OF PAYMENT OF FEES SUPPORT PROVIDED BY THE IR OFFICE The dollar payments can be made in any of the following Once accepted as a visiting/exchange student at IIT Bombay, the ways:- IR office will coordinate with the student to provide the following 1. Travellers cheques / Bankers cheques / Demand Draft in facilities: US Dollars (USD) or equivalent in Indian Rupees (lNR), in • Send Admission Offer Letter for visa purposes, favour of "Registrar, IIT Bombay". -

Jennings on the Trail of Pessoa Or Dimensions of Poetical Music

Jennings on the Trail of Pessoa or dimensions of poetical music Pedro Marques* Keywords Fernando Pessoa, Hubert Jennings, Roy Campbell, Peter Rickart, translation, versification, musicality, The thing that hurts and wrings, What grieves me is not, What saddens me is not. Abstract Here we present two unpublished essays by Hubert Jennings about the challenges of translating the poetry of Fernando Pessoa: the first one of them, brief and fragmentary, is analyzed in the introduction; the second, longer and also covering issues besides translation, is presented in the postscript. Having as a starting point the Pessoan poem “O que me doe” and three translations compared by Hubert Jennings, this presentation examines some aspects of poetic musicality in the Portuguese language: verse measurement, stress dynamics, rhymes, anaphors, and parallelisms. The introduction also discusses how much the English versions of the poem, which are presented by Jennings, recreate (or not) the musical-poetic dimensions of the original text. Palavras-chave Fernando Pessoa, Hubert Jennings, Roy Campbell, Peter Rickart, tradução, versificação, musicalidade, O que me doe, O que me dói. Resumo Reproduzem-se aqui dois ensaios inéditos de Hubert Jennings sobre os desafios de se traduzir a poesia de Fernando Pessoa: o primeiro deles, breve e fragmentário, é analisado numa introdução; o segundo, mais longo e versando também sobre questões alheias à tradução, é apresentado em postscriptum. A partir do poema pessoano “O que me dói” e de três traduções comparadas por Hubert Jennings, esta apresentação enfoca alguns aspectos da música poética em língua portuguesa: medida do verso, dinâmica dos acentos, rimas, anáforas e paralelismos. -

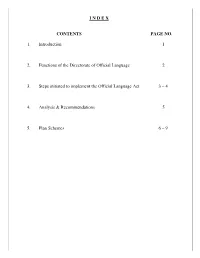

CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate Of

I N D E X CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language 2 3. Steps initiated to implement the Official Language Act 3 – 4 4. Analysis & Recommendations 5 5. Plan Schemes 6 – 9 - 1 - 1. Introduction : In accordance with the Government of Goa, the Directorate of Official Language was established in 2004 as an independent Department of Government of Goa and entrusted with the nodal responsibility for all matters relating to the progressive use of Konkani as the Official Language of the State of Goa. As per the Government the Directorate adopted Konkani as the Official Language of the then Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu and accordingly the Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act 1987 (Act 5 of 1987) was enacted in pursuance of Section 34 of the Government of Union Territories Act, 1963 (Central Act 20 of 1963), Official Language Act 1987 which provides Konkani shall be the Official Language whereas, Marathi shall be used for all or any of the Official purposes. The Act envisaged the continuance of the English language of for official purposes in addition to Konkani & Marathi languages. - 2 - 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language : Its main functions include, inter-alia, the following : i. Enhancing the efficacy of Official language the Department releases recurring grants in aid to Goa Konkani Akademi. The Goa Konkani Akademi was established by the Government of Goa in the year 1984. ii. Recurring Grants in aid to Gomantak Marathi Academy for promoting Marathi language. The Gomantak Marathi Academy is an autonomous, sovereign Institution and was registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, bearing registration No. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

A STUDY of L2 KANJI LEARNING PROCESS Analysis of Reading and Writing Errors of Swedish Learners in Comparison with Level-Matched Japanese Schoolchildren

A STUDY OF L2 KANJI LEARNING PROCESS Analysis of Reading and Writing Errors of Swedish Learners in Comparison with Level-matched Japanese Schoolchildren Fusae Ivarsson Department of Languages and Literatures Doctoral dissertation in Japanese, University of Gothenburg, 18 March, 2016 Fusae Ivarsson, 2016 Cover: Fusae Ivarsson, Thomas Ekholm Print: Reprocentralen, Campusservice Lorensberg, Göteborgs universitet, 2016 Distribution: Institutionen för språk och litteraturer, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, SE-405 30 Göteborg ISBN: 978-91-979921-7-6 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/41585 ABSTRACT Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 18 March, 2016 Title: A Study of L2 Kanji Learning Process: Analysis of reading and writing errors of Swedish learners in comparison with level-matched Japanese schoolchildren. Author: Fusae Ivarsson Language: English, with a summary in Swedish Department: Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden ISBN: 978-91-979921-7-6 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/41585 The present study investigated the characteristics of the kanji learning process of second language (L2) learners of Japanese with an alphabetic background in comparison with level-matched first language (L1) learners. Unprecedentedly rigorous large-scale experiments were conducted under strictly controlled conditions with a substantial number of participants. Comparisons were made between novice and advanced levels of Swedish learners and the respective level-matched L1 learners (Japanese second and fifth graders). The experiments consisted of kanji reading and writing tests with parallel tasks in a practical setting, and identical sets of target characters for the level-matched groups. Error classification was based on the cognitive aspects of kanji. -

S Goesas Em Konkani Songs From

GOENCHIM KONKNI GAIONAM 1 CANÇO?S GOESAS EM KONKANI2 SONGS FROM GOA IN KONKANI 1 Konkani 2 Portuguese 1 Goans spoke Portuguese but sang in Konkani, a language brought to Goa by the Indian Arya. + A Goan way of expressing love: “Xiuntim mogrim ghe rê tuka, Sukh ani sontos dhi rê maka.” These Chrysanthemum and Jasmine flowers I give to thee, Joy and happiness give thou to me. 2 Bibliography3 A selection as background information Refer to Pereira, José / Martins, Micael. “Goa and its Music”, in: UUUUBoletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Nr.155 (1988) pp. 41-72 (Bibliography 43-55) for an extensive selection and to the Mando Festival Programmes published by the Konkani Bhasha Mandal in Panaji for recent compositions. Almeida, Mathew . 1988. Konkani Orthography. Panaji: Dalgado Konknni Akademi. Barreto, Lourdinho. 1984. Goemchem Git. Pustok 1 and 2. Panaji: Pedro Barreto, Printer. Barros de, Joseph. 1989. “The first Book to be printed in India”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 159. pp. 5-16. Barros de, Joseph. 1993. “The Clergy and the Revolt in Portuguese Goa”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 169. pp. 21-37. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). 2000. Goa and Portugal. History and Development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). Goa´s formost Nationalist: José Inácio Candido de Loyola. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. (Loyola is mentioned in the mando Setembrachê Ekvissavêru). Bragança, Alfred. 1964. “Song and Music”, in: The Discovery of Goa. Panaji: Casa J.D. Fernandes. pp. 41-53. Coelho, Victor A. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

Print ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KAITHAL Revision identity applications have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) 1. List number 15/07/2019 15/07/2019 3. Place of hearing* Serial Date of Name of Name of Father / Mother / Husband Date of Time of number$ of Place of residence receipt claimant and (Relationship)# hearing* hearing* application Mohan 259, Sirta Kaithal, V. P. O. 1 15/07/2019 Suresh Kumar (F) Malik Sirta, , KAITHAL ANKIT 283B, HOUSING BOARD COLONY, 2 15/07/2019 OM PARKASH SINGLA (F) SINGLA JIND ROAD, KAITHAL, , KAITHAL £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location Date of exhibition at designated location Electoral Registration * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer under rule 15(b) Officer’s Office under rule $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. (F), (M), (H) 26/07/2019 Print ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KAITHAL Revision identity applications have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) 1. List number 16/07/2019 16/07/2019 3.