Policy Reforms for Safe Online Access to Alcoholic Beverages in Indonesia by Pingkan Audrine 2 Policy Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alcohol Policy in Muslim Countries in the Asean Community

ALCOHOL POLICY IN MUSLIM COUNTRIES IN THE ASEAN COMMUNITY 1AKARAWIN SASANAPITAK, 2SUKANLAYA KONGPRADIT, 3JINDA THOMRONGAJARIYAKUL 1,3Department of Local Government, 2Department of Mass Communication, Phranakhon Si Ayutthaya Rajabhat University, Thailand E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - The objectives of this paper are to study the alcohol policies in Muslim countries in the ASEAN Community and to compare alcohol policies among these countries. This qualitative research is conducted be examining documents concerning the alcohol policies in Muslim countries in the ASEAN Community--i.e., Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The result of the study indicates that all these countries have a wide range of the alcohol policies including investment policy, import policy, drink age policy, retailing policy, drink-drive policy, advertising policy, and area policy. Keywords - Alcohol policy, Alcohol consumption, ASEAN, Muslim I. INTRODUCTION law called “Shari’ah” is the main law Brunei has implemented for governing the country [1]. Alcohol policy measures have been implemented by Therefore, the result of alcohol consumption in the every country to control alcohol consumption among country is relatively low, about 0.6 liters per person their citizens. They aim to reduce alcohol drinking per year, and most of consumers are men rather than and problems caused by alcohol consumption such as women [2], especially in Chinese-Brunei and tourists. road accidents, health problems, and family violence. Nevertheless, drinking and carrying alcohol in public In particular, Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia, the are prohibited. three Muslim countries in the ASEAN Community, Brunei has a specific law for controlling alcohol have quite strict alcohol control policy measures consumption called as "Brunei's alcohol laws" that based on Islamic Law (Shari'ah) which is the the following measures: religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition. -

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

An Examination of the Legal Marijuana Use Age and Its Enforcement in California, a State Where Recreational Marijuana Is Legal

An examination of the legal marijuana use age and its enforcement in California, a state where recreational marijuana is legal March 2021 James C. Fell NORC at the University of Chicago Traci Toomey University of Minnesota Angela H. Eichelberger Insurance Institute for Highway Safety Julie Kubelka NORC at the University of Chicago Daniel Schriemer Darin Erickson University of Minnesota Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 4 METHOD ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Enforcement of minimum legal marijuana use age of 21 (MLMU-21) laws ...................................... 6 Pseudo-underage patron entry attempts ............................................................................................... 7 Sample design ............................................................................................................................ 8 Recruitment of pseudo-underage patrons ................................................................................. 9 Data collection protocol ............................................................................................................ 9 RESULTS .................................................................................................................................................. -

Forbidden Transactions and Black Markets

Forbidden Transactions and Black Markets Chenlin Gu,∗ Alvin E. Roth,y and Qingyun Wuzx Abstract Repugnant transactions are sometimes banned, but legal bans sometimes give rise to active black markets that are difficult if not impossible to extinguish. We explore a model in which the probability of extinguishing a black market depends on the extent to which its transactions are regarded as repugnant, as measured by the proportion of the population that disapproves of them, and the intensity of that repugnance, as measured by willingness to punish. Sufficiently repugnant markets can be extinguished with even mild punishments, while others are insuf- ficiently repugnant for this, and become exponentially more difficult to extinguish the larger they become. (JEL D47, K42, P16) Keywords: black market; repugnance; Markov process. 1 Introduction Why are drug dealers plentiful, but hitmen scarce? I.e. why is it relatively easy for a newcomer to the market to buy illegal drugs, but hard to hire a killer? Both of those transactions come with harsh criminal penalties, vigorously enforced: In the U.S., half of Federal prisoners have drug convictions,1 and murder for hire is treated ∗DMA, Ecole Normale Sup´erieure,PSL Research University, Paris 75230, France (email: chen- [email protected]). yDepartment of Economics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, United States (email: al- [email protected]). zDepartment of Economics, and Department of Management Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, United States (email: [email protected]). xWe thank Itai Ashlagi, Fuhito Kojima, Jean-Christophe Mourrat, Muriel Niederle, Andrei Shleifer, Gavin Wright, Zeyu Zheng and Zhengyuan Zhou for helpful discussions. -

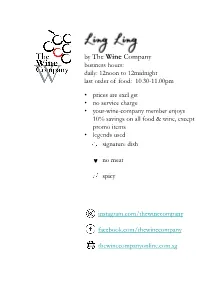

Ling Ling by the Wine Company Page 1 of 19 Nibbles

by The Wine Company business hours: daily: 12noon to 12midnight last order of food: 10.30-11.00pm • prices are excl gst • no service charge • your-wine-company member enjoys 10% savings on all food & wine, except promo items • legends used signature dish no meat spicy instagram.com/thewinecompany facebook.com/thewinecompany thewinecompanyonline.com.sg lunch available from 12pm to 3pm with complimentary coffee or tea or ice lemon tea hot dog 3.90 1 pc of hot dog with mustard; bun is lightly toasted add $1 for egg or avocado or bacon cream of mushroom 5.90 180g, made-from-scratch, assorted mushrooms, blended with cream drizzled with truffle oil; served with sugar cheese bun caesar salad 6.90 130g, a la minute of romaine lettuce, tomatoes, quail eggs, bacon bits, croutons, pine nuts and parmesan cheese pig trotter beehoon 6.90 150g, traditional hokkien comfort food, simple and oh so yummy cantonese porridge 6.90 porridge flavored with bone stock; garnished with spring onion, ginger & fried dough choice of chicken or pork add one century egg or one salted egg for $1.90 curry chicken 6.90 a concoction of singapore and malaysia style curry chicken fragrant steamed rice complimentary from the menu 30% savings select from mains, pasta and desserts price excl gst Ling Ling by The Wine Company page 1 of 19 nibbles fried ikan bilis and peanuts 4.90 130g of local anchovies; delicious and crunchy this is available until closing time recommend to pair with your favourite wine classic papadum 4.90 8pcs of indian-styled wafers served with cucumber-yogurt -

Halal Development: Trends, Opportunities and Challenges

HALAL DEVELOPMENT: TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES PROCEEDINGS OF THE 1ST INTERNATIONALCONFERENCE ON HALAL DEVELOPMENT (ICHAD 2020), MALANG, INDONESIA, 8 OCTOBER 2020 Halal Development: Trends, Opportunities and Challenges Edited by Heri Pratikto & Ahmad Taufiq Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia Adam Voak Deakin University, Australia Nurdeng Deuraseh Universitas Islam Sultan Sharif Ali, Brunei Darussalam Hadi Nur Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Indonesia Winai Dahlan The Halal Science Center Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand Idris & Agus Purnomo Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia CRC Press/Balkema is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 The Author(s) Typeset by MPS Limited, Chennai, India The right of the first International Conference on Halal Development (ICHaD2020) to be identified as author[/s] of this work has been asserted by him/her/them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The Open Access version of this book, available at www.taylorfrancis.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 license. The Open Access version of this book will be available six months after its first day of publication. Although all care is taken to ensure integrity and the quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the author for any damage to the property or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information -

27 Bukit Timah Road, Balmoral Plaza #0

27 Bukit Timah ROAd, Balmoral Plaza #0-07, SINGAPORE 259708 OPERATING HOURS for reservations EMAIL us FACEBOOK INSTAGRAM .00AM - 0.30AM whatsapp 8688 5393 [email protected] De’Pillars Bistro depillarsbistro STARTERS & SNACKS M7 BREADED PRAWNS 5 PIECES $2.90 M8 DEEP FRIED BREADED CALAMARI 5 PIECES $8.90 M9 FRIED SPICY JUMBO CHICKEN WING 3 PIECES $8.90 M0 SPICY FRENCH FRIES $6.90 SALAD M POTATO WEDGES $6.00 M GRILLED CHICKEN $.90 M2 FRENCH FRIES $6.00 M2 MIXED GARDEN $.90 GRILL SPECIALS APPETIZER M3 GRILLED NEW ZEALAND AIR FLOWN $26.90 M3 TOMATO BRUSCHETTA $3.90 RIB EYE STEAK M4 GARLIC BREAD $8.90 M4 BRAISED LAMB SHANK $24.90 M5 GRILLED ATLANTIC SALMON $24.90 M6 GRILLED LAMB CHOPS $9.90 M7 GRILLED CHICKEN BREAST $6.90 soup LOCAL STARTERS M5 TOM YUM SEAFOOD $3.90 M8 GRILLED MUTTON SATAY 0 PIECES $2.00 M6 MUSHROOM $8.90 M9 GRILLED CHICKEN SATAY 0 PIECES $.00 M2 SPRING ROLLS 6 PIECES $6.90 M22 ONION RINGS $6.00 M23SAMOSA $6.00 M24 KETUPAT $2.00 SPICY SPECIALITY NOODLES our SPECIALITY M25SEAFOOD HOR FUN $0.90 ASIAN & LOCAL CUISINE M26BEEF HOR FUN $0.90 M45 STIR FRIED BLACK PEPPER BEEF $5.90 M27 MEE GORENG CHICKEN / MUTTON / SEAFOOD $8.90 M46HOTPLATE EGG TOFU & SPRING ONION $5.90 M28KWAY TEOW GORENG CHICKEN / MUTTON / SEAFOOD $8.90 M47 CRISPY CHICKEN WITH THAI $5.90 M29MAGGI MEE GORENG CHICKEN / MUTTON / SEAFOOD $8.90 CHILLI SAUCE M30BEE HOON GORENG CHICKEN / MUTTON / SEAFOOD $8.90 M48SEAFOOD MIXED VEGETABLES $5.90 M3 BEE HOON GORENG IKAN BILIS $8.90 M49STIR FRIED BROCCOLI WITH PRAWNS $2.90 M50KANGKONG BELACAN $0.90 M5 BABY KAILAN WITH OYSTER -

Issues in the Implementation and Evolution of the Commercial

International Journal of Drug Policy 27 (2016) 1–12 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Editors’ Choice Issues in the implementation and evolution of the commercial § recreational cannabis market in Colorado a, b a Todd Subritzky *, Simone Pettigrew , Simon Lenton a National Drug Research Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia b School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Kent St, Bentley, WA, 6102, Australia A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: For almost a century, the cultivation, sale and use of recreational cannabis has been Received 21 September 2015 prohibited by law in most countries. Recently, however, under ballot initiatives four states in the US have Received in revised form 27 November 2015 legalised commercial, non-medical (recreational) cannabis markets. Several other states will initiate Accepted 1 December 2015 similar ballot measures attached to the 2016 election that will also appoint a new President. As the first state to implement the legislation in 2014, Colorado is an important example to begin investigating early Keywords: consequences of specific policy choices while other jurisdictions consider their own legislation although Cannabis the empirical evidence base is only beginning to accrue. Regulation Method: This paper brings together material sourced from peer reviewed academic papers, grey Colorado Marijuana literature publications, reports in mass media and niche media outlets, and government publications to Testing outline the regulatory model and process in Colorado and to describe some of the issues that have Edibles emerged in the first 20 months of its operation. -

Legalization of Cannabis in Canada: Implementation Strategies and Public Health

LC LSIC Inquiry into Use of Cannabis in Victoria Submission 347 Inquiry into the use of Cannabis in Victoria Organisation Name: Your position or role: SURVEY QUESTIONS Drag the statements below to reorder them. In order of priority, please rank the themes you believe are most important for this Inquiry into the use of Cannabis in Victoria to consider:: Accessing and using cannabis,Education,Mental health,Public health,Social impacts,Young people and children,Public safety,Criminal activity What best describes your interest in our Inquiry? (select all that apply) : Individual Are there any additional themes we should consider? Select all that apply. Do you think there should be restrictions on the use of cannabis? : Personal use of cannabis should be legal. ,Sale of cannabis should be legal and regulated. ,Cultivation of cannabis for personal use should be legal.,There should be no restrictions. YOUR SUBMISSION Submission: Every term of reference can be cut and copied from Canada's implementation. If required, sale of cannabis can be done just as tobacco sales have been implemented, which would include the restrictions to underage people. Minimising the risk of underage people growing cannabis at home for personal use can be managed by advertising to parents with honest, non-divisive, independent science based studies, all of which are available to be copied from Canada's implementation. Do you have any additional comments or suggestions?: People should not live in fear of growing or utilising a plant. The illegality of Cannabis and crime surrounding it is because it is illegal, that's all. Decriminalise and permit either personal or public production stops the criminality and all associated negative impacts. -

PREPARED by ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT for Further Enquiries, Please Contact Customs Call Center

PREPARED BY ROYAL MALAYSIAN CUSTOMS DEPARTMENT For further enquiries, please contact Customs Call Center : 1 300 88 8500 (General Enquiries) Operation Hours Monday - Friday (8.30 a.m – 7.00 p.m) email: [email protected] For classification purposes please refer to Technical Services Department. This Guide merely serves as information. Please refer to Sales Tax (Goods Exempted From Tax) Order 2018 and Sales Tax (Rates of Tax) Order 2018. Page 2 of 130 NAME OF GOODS HEADING CHAPTER EXEMPTED 5% 10% Live Animals (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Live Bee (Lebah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Boar (Babi Hutan) 01.03 01 ✔ Live Buffalo (Kerbau) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Camel (Unta) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Cat (Kucing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Chicken (Ayam) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Cow (Lembu) 01.02 01 ✔ Live Deer (Rusa) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Dog (Anjing) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Duck (Itik) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Elephant (Gajah) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Frog (Katak) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Geese (Angsa) 01.05 01 ✔ Live Goat (Kambing) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Horse (Kuda) 01.01 01 ✔ Live Oxen 01.02 01 ✔ Live Pig 01.03 01 ✔ Live Quail (Puyuh) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Rabbit (Arnab) 01.06 01 ✔ Live Sheep (Biri-biri) 01.04 01 ✔ Live Turkey (Ayam Belanda) 01.05 01 ✔ Meat & Edible Meat Offal (Subject to an import/export license from the relevant authorities) Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Fresh/ Chilled) 02.01 02 ✔ Beef Bone (Tulang Lembu) (Frozen) 02.02 02 ✔ Belly (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ Frozen) 02.03 02 ✔ Boneless Ham (Of Pig) (Fresh/ Chilled/ 02.03 02 ✔ Frozen) This Guide merely serves as information. -

Alcohol in the Soviet Underground Economy"

ALCOHOL IN THE SOVIET UNDERGROUN D ECONOM Y b y Vladimir G . Trem l Paper No .5, December 1985 Library of Congress Catalog Card Numbe r 85-73407 TABLE 0F CONTENT S Forewor d i i 1 . Introduction 1 ALC0HOL IN THE SOVIET UNDERGROUND EC0NOMY 2 . Samogon 2 3 . Theft of Alcohol 1 6 by Vladimir G . Treml 4 . Abuses in Trade 2 3 Duke University 5 . Vodka as Money 2 7 6 . Sources and Bibliography 3 9 Footnotes 4 2 References Cited 5 3 Appendix 62 December 198 5 To be published in STUDIES IN THE SECOND ECONOMY OF THE COM - MUNIST COUNTRIES, edited by Gregory Grossman, University o f California Press, Berkeley, California, 1986 . ii i FOREWORD The research for this study was completed In early 1982 but the pape r Accordingly, the study and its conclusions can be viewed as curren t itself remained somewhat unfinished waiting for completion of the Berkeley - despite the cutoff of Soviet sources in early 1982 . Duke emigre survey which provided the author with estimates of such phenomen a In May of 1985 Soviet authorities launched a new and tar-reaching anti - as the theft of technical alcohol from places of employment, the use o f drinking campaign marked by higher penalties for drunkenness, increase d different inputs in illegal home distillation of alcohol, purchases and price s restrictions on the sale of alcoholic beverages, and a projected reduction i n of samogon, and the like . Computerization of the emigre questionnaire wa s the output of vodka and fruit wine . Penalties for making, selling and buyin g completed by mid-1985, and so was the paper . -

DIGITAL NOMAD Guide to Thailand, Vietnam & Indonesia Table of Contents

GoToLaunch Guides present DIGITAL NOMAD guide to Thailand, Vietnam & Indonesia Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction About This Guide: What to Expect Asia Culture Guide Chapter 2: Thailand Country Guide: Thailand Culture Guide: Thailand Visa Guide: Entering and Staying in Thailand City Guide: Bangkok City Guide: Chiang Mai Chapter 3: Vietnam Country Guide: Vietnam Culture Guide: Vietnam Visa Guide: Entering and Staying in Vietnam City Guide: Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) Chapter 4: Indonesia Country Guide: Indonesia Culture Guide: (Bali) Indonesia Visa Guide: Entering and Staying in Indonesia City Guide: Bali Chapter 5: Conclusion Copyright ©2015 Wood Egg SPRL (as “GoToLaunch”) Writing: Michael Gasiorek Research: Nico Jannaush, Anouar Tahiri Book design: Ting Kelly (DoorstepStudios.com) Editing & General Oversight: Janet Chang Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 5 GoToLaunch Guides ABOUT THIS GUIDE: WHAT TO EXPECT The day you wake up to the sound of waves lapping at the sand steps away from your bungalow, a fresh breakfast of eggs and fruit waiting for you next to your laptop, with everything else you own stuffed in a small backpack that has been with you across the world - it might feel like you’ve made it. In this life, you might have less than 100 items to your name, trading in beautiful clothes, homes, and cars for access to incredible experiences on every continent. Your livelihood will depend on your access to good WiFi. You might think of it like a fundamental human right. Your now twice-extended passport might have more stamps than a post office, or you may have fallen in love with the first place you drop into.