Rural Class Differentiation in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria

l- World Health Organization African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control FINAL RËPOftî ,i ={ Evaluation of the Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI Project, Nigeria N ove m ber- Decem ber 2004 Elizabeth Elhassan (Team Leader) Uwem Ekpo Paul Kolo William Kisoka Abraraw Tefaye Hilary Adie f'Ï 'rt\ t- I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Table of contents............. ..........2 Abbreviations/Acronyms ................ ........ 3 Acknowledgements .................4 Executive Summary .................5 *? 1. lntroduction ...........8 2. Methodology .........9 2.1 Sampling ......9 2.2 Levels and lnstruments ..............10 2.3 Protocol ......10 2.4 Team Composition ........... ..........11 2.5 Advocacy Visits and 'Feedback/Planning' Meetings........ ..........12 2.6 Limitations ..................12 3. Major Findings And Recommendations ........ .................. 13 3.1 State Level .....13 3.2 Local Government Area Level ........21 3.3 Front Line Health Facility Level ......27 3.4 Community Level .............. .............32 4. Conclusions ..........36 4.1 Grading the Overall Sustainability of the Niger State CDTI project.................36 4.2 Grading the Project as a whole .......39 ANNEXES .................40 lnterviews ..............40 Schedule for the Evaluation and Advocacy.......... .................42 Feedback and Planning Meetings, Agenda.............. .............44 Report of the Feedbacl</Planning Meetings ..........48 Strengths And Weaknesses Of The Niger State Cdti Project .. .. ..... 52 Participants Attendance List .......57 Abbrevi -

Focus on Niger State Housing Corportation – Being an Article for Journal Publication In

Housing Today: The Journal of the Association of Housing Corporations of Nigeria, Volume 8, No. 3, November 1992, Pp. 62-70 FOCUS ON NIGER STATE HOUSING CORPORATION (N.S.H.C.) Mohammed, A.; Bobi, M.T.; Minin, U.; Babalola, O.; Shaaba, A.P.; Namagana, N.M.; Olukade, I.J. and Bako, M.D. @Niger State Housing Corporation, P.M.B 105 Minna, Niger State, Nigeria Abstract: Established in 1979, Niger State Housing Corporation (NSHC)had the primary responsibility to address qualitative and quantitative housing inadequacy in Niger State, thereby enhancing the standard of living of her citizens, this article with the aim of elucidating the activities of the Corporation for performance rating , has the objectives to examine its consultancy and contracting services, and to assess its home ownership and other programmes. The methodology adopted for the study was the qualitative research design method which provides description of case studies with purposive sampling, hence the analyses also. The results of the study concluded that the NSHC’s performance from inception to date has been very satisfactory, and recommended that the Corporation enhances its programmes and continue to discharge its responsibilities to Nigerian citizens in the State with more enlightenment about its activities. Keywords: Consultancy, contracting, direct-labor, housing, tenure. ARTICLE OUTLINE Alhaji Isa Mohammed Kagara was 1.0 Introduction appointed secretary. They were replaced in 2.0 Relevant Review Works November, 1984, by Arc. Mustapha 3.0 Research Methodology Zubairu and Alhaji Mohammed Isa Ekkan 4.0 Data Presentation, Analyses and Discussion respectively, in September 1990 Mallam 5.0 Conclusion Mohammed Tukur Bobi was appointed the References new Secretary of the Corporation. -

International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies (LALIGENS), Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

1 LALIGENS, VOL. 8(2), S/N 18, AUGUST/SEPT., 2019 International Journal of Language, Literature and Gender Studies (LALIGENS), Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 8 (2), Serial No 18, August/Sept., 2019:1-12 ISSN: 2225-8604(Print) ISSN 2227-5460 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/laligens.v8i2.1 BABEL OF NIGER STATE 1IHENACHO, A. A., JAMIU, A. M., AGU, M. N., EBINE, S. A., ADELABU, S. & OBI, E. F. Faculty of Languages and Communication Studies IBB University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria 1+2348127189382 [email protected] Abstract This paper is a preliminary report on an ongoing research being carried out in the Faculty of Languages and Communication Studies of Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria. The research is on ‘Language education and translation in Niger State’. The languages involved in the research are: Arabic, English, French, Gbagyi, Hausa and Nupe. The aim of this research which is funded by the Nigerian Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) is ‘to help improve the outcome of language education and translation in Niger State in both quality and quantity’ As a preliminary inquiry, the research team visited 78 institutions of learning at all levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) in all the three geopolitical zones of Niger State, as well as media houses located in the capital, Minna, and obtained responses to the questionnaires they took to the institutions. While pursuing the aim and objectives of their main research, the team deemed it necessary to consider the position (and the plight) of the multiplicity of other languages of Niger State (than the three major ones – Gbagyi, Hausa and Nupe) in relation to Nigeria’s language policy in education. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 10 June, 2021

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 66 2297 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 10 June, 2021 1. The House met at 11.45 a.m. Mr Deputy Speaker read the Prayers. 2. The House recited the National Pledge 3. Votes and Proceedings Mr Deputy Speaker announced that he had examined and approved the Votes and Proceedings of Wednesday, 9 June, 2021. The Votes and Proceedings was adopted by unanimous consent. 4. Petitions (i) A petition from Ijeoma Unachukwu and family, on the killing of her husband, Oguchi Unachukwu, who was shot by officers of the Nigerian Air Force stationed at Sam Mbakwe International Airport checkpoint, was presented and laid by Hon. Henry Nwawuba (Mbaitoli/Ikeduru Federal Constituency); (ii) A petition from Orji O. U., on the death of her daughter, Glory Chinenye Nwokocha, who was killed in a cross fire between members of the Indegenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and officers of the Nigerian Army, was presented and laid by Hon. Onuigbo Samuel Ifeanyi (Ikwuano/Umuahia North/South Federal Constituency). Petitions referred to the Committee on Public Petitions. 5. Matter of Urgent Public Importance (Standing Order Eight, Rule 4) Need to Secure the Release of 136 Abducted School Children From Tegina in Rafi Local Government Area and Rejig Security Architecture to Curb the Worsening Insecurity in Niger State: Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi (Bida/Gbako/Katchia Federal Constituency and 9 others) introduced the matter and prayed the House to: (a) consider and approve the matter as one of urgent public importance; and (b) suspend Order Eight, Rule 4 (3) to allow debate on the matter forthwith. -

Facts and Figures About Niger State Table of Content

FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT NIGER STATE TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE DESCRIPTION PAGE Map of Niger State…………………………………………….................... i Table of Content ……………………………………………...................... ii-iii Brief Note on Niger State ………………………………………................... iv-vii 1. Local Govt. Areas in Niger State their Headquarters, Land Area, Population & Population Density……………………................... 1 2. List of Wards in Local Government Areas of Niger State ………..…... 2-4 3. Population of Niger State by Sex and Local Govt. Area: 2006 Census... 5 4. Political Leadership in Niger State: 1976 to Date………………............ 6 5. Deputy Governors in Niger State: 1976 to Date……………………...... 6 6. Niger State Executive Council As at December 2011…........................ 7 7. Elected Senate Members from Niger State by Zone: 2011…........…... 8 8. Elected House of Representatives’ Members from Niger State by Constituency: 2011…........…...………………………… ……..……. 8 9. Niger State Legislative Council: 2011……..........………………….......... 9 10. Special Advisers to the Chief Servant, Executive Governor Niger State as at December 2011........…………………………………...... 10 11. SMG/SSG and Heads of Service in Niger State 1976 to Date….….......... 11 12. Roll-Call of Permanent Secretaries as at December 2011..….………...... 12 13. Elected Local Govt. Chairmen in Niger State as at December 2011............. 13 14. Emirs in Niger State by their Designation, Domain & LGAs in the Emirate.…………………….…………………………..................................14 15. Approximate Distance of Local Government Headquarters from Minna (the State Capital) in Kms……………….................................................. 15 16. Electricity Generated by Hydro Power Stations in Niger State Compare to other Power Stations in Nigeria: 2004-2008 ……..……......... 16 17. Mineral Resources in Niger State by Type, Location & LGA …………. 17 ii 18. List of Water Resources in Niger State by Location and Size ………....... 18 19 Irrigation Projects in Niger State by LGA and Sited Area: 2003-2010.…. -

Nigeria Resource Tracking in Health in Nigeria

Report No: AUS0000313 . Nigeria Public Disclosure Authorized Resource Tracking in Health in Nigeria Volume II . March 26, 2018 . HNP Public Disclosure Authorized . Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 . © 2017 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: “World Bank. 2018. Resource Tracking in Health in Nigeria. © World Bank.” All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. 2 RESOURCE TRACKING IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN NIGERIA: CASE STUDY FROM NIGER AND EKITI STATES VOLUME II March 26, 2018 GHN07 Bernard Gauthier, Obert Pimhidzai, Karima Saleh 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... -

NIGER ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS.Cdr

ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS NIGER STATE ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS Niger State With the sophistication with which kidnappings are strategically orchestrated and masterminded in Niger State especially, speculations are rife that either these violent acts against humanity are financially motivated or geared towards eradicating Western education proposed by Boko Haram. With school students continually constituting a soft target with which kidnappers have found a haven, there is no gainsaying that if the situation is not urgently ameliorated, education in the Northern part of Nigeria may gradually go into extinction. The deplorable security situation in Niger State cannot be over-flogged. However, racial profiling of crime activities seems to blur analyzing these insecurity situations from the perspective of the motives behind the heightened spate of kidnapping that seems to overwhelm the nation's security detail. REVIEW OF SIX MONTHS INCIDENTS FROM OCTOBER 2020 TO MARCH 2021 (Source: Nigerian dailies) February 2, 2021 Assailants numbering about 250 stormed the four villages (Kurege, Sabon Gida, Sararai and Rafin Kanya) in Shiroro LGA on motorcycles, killing about 21 locals and abducting not less than 40 persons. The attack was said to be because the community failed to participate in the meeting where negotiations between the community leaders and terrorists to conclude on December 14, 2020: the attendant fees to be paid by farmers for seamless farming and About 19 persons were kidnapped harvesting of crops without and a clergyman killed by gunmen intermittent attacks. at Ogu and Tegina communities March 31, 2021 in Rafia LGA Six persons, including five military officers and one Civil Defense October 12, 2020: Officer, were feared killed in a Gunmen suspected to be bandits bandits attack on five communities killed three persons (the son and (Allawa, Manta, Gurmana, Bassa younger brother of the village head and Kokki) in Shiroro LGA. -

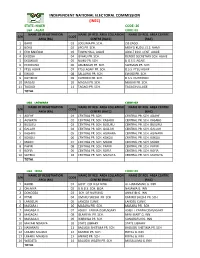

Niger Code: 26 Lga : Agaie Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: NIGER CODE: 26 LGA : AGAIE CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 BARO 01 LOGUMA PR. SCH. JSS ZAGO 2 BOKU 02 JIPO PR. SCH. MOH'D KUDU J.S.S. NAMI 3 EKO BADEGGI 03 TOWN HALL, AGAIE ADULT EDU. CENT. AGAIE 4 EKOSSA 04 ISYAKU PR. SCH. DENDO SECRETARY SCH. AGAIE 5 EKOWUGI 05 NUHU PR. SCH. D.G.S.S. AGAIE 6 EKOWUNA 06 ABUBAKAR PR. SCH. SWEMAN PR. SCH. 7 ETSU AGAIE 07 ETSU AGAIE PR. SCH. D.S.S. ETSU AGAIE 8 EWUGI 08 SALLAWU PR. SCH. EWUGI PR. SCH. 9 KUTIRIKO 09 KUTIRIKO PR. SCH. D.S.S. DUTRIRIKO 10 MAGAJI 10 MAGAJI PR. SCH. MAGAJI PR. SCH. 11 TAGAGI 11 TAGAGI PR. SCH. TAGAGI VILLAGE TOTAL LGA : AGWARA CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ADEHE 01 CENTRAL PR. SCH. CENTRAL PR. SCH. ADAHE 2 AGWATA 02 CENTRAL PR. SCH. KASABO CENTRAL PR. SCH. KASABO 3 BUSUEU 03 CENTRAL PR. SCH. BUSURU CENTRAL PR. SCH. BUSURU 4 GALLAH 04 CENTRAL PR. SCH. GALLAH CENTRAL PR. SCH. GALLAH 5 KASHINI 05 CENTRAL PR. SCH. AGWARA CENTRAL PR. SCH. AGWARA 6 KOKOLI 06 CENTRAL PR. SCH. KOKOLI CENTRAL PR. SCH. KOKOLI 7 MAGO 07 CENTRAL PR. SCH. MAGO CENTRAL PR. SCH. MAGO 8 PAPIRI 08 CENTRAL PR. SCH. PAPIRI CENTRAL PR. SCH. PAPIRI 9 ROFIA 09 CENTRAL PR. -

Application of Remote Sensing Techniques in Hydrogeological Mapping of Parts of Bosso Area, Minna, North-Central Nigeria

International Journal of the Physical Sciences Vol. 5(9), pp. 1465-1474, 18 August, 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS ISSN 1992 - 1950 ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Application of remote sensing techniques in hydrogeological mapping of parts of Bosso Area, Minna, North-Central Nigeria A. N. Amadi* and P. I. Olasehinde Department of Geology, Federal University of Technology, P. M. B. 65, Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. Accepted 5 July, 2010 The study focuses on the hydrogeological mapping of Bosso area of Minna, Niger State using remote sensing techniques whilst considering integration of geophysical and hydrogeological investigation in a synergistic approach. Landsat enhanced thematic mapper band 4 and 7 were used for the study. The satellite imagery that was acquired from Global Land Cover Facility website was rectified and geo- referenced using various ground control points that were obtained during ground thruthing. The analysis of the imageries using ILWIS 3.3’s included filtering, stretching clustering. The outcome module gives results on both the structure and the lithology of the area. Structural elements that were remotely mapped are majorly lineaments which trend NW-SE and NE-SW. These were correlated with the results of the field mapping and radial geo electric sounding results. The geological map shows principal NE-SW trending joint with minor NW-SE direction. The radial geo-electric sounding at three different locations as interpreted from the anisotropic polygons showed NW-SE, NE-SW and N-S fracture directions respectively. There are three basic rock types that are represented in this region which include; N-S trending schist in the western part and around the water bodies (Bosso Dam and River Chanchaga), granite in the Northern and Southern parts of the area and gneiss in the central part. -

Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission Public Private Partnership Projects Pipeline

INFRASTRUCTURE CONCESSION REGULATORY COMMISSION PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP PROJECTS PIPELINE In furtherance of the mandate of the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission to provide guidance and regulations for Infrastructure Public Private Partnerships (PPPs); and pursuit to Section 2(4) of the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission (Establishment, etc) Act 2005, this is a publication of Federal Government projects eligible for PPP contracts. The projects are in line with the transformation agenda of the President, His Excellency, Dr. Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, GCFR, and are being developed by relevant Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) of the Federal Government, with the guidance of the ICRC and in line with the Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission Act 2005, and the National Policy on PPPs (N4P). 2013 PPP Pipeline Project List Up-Date S/N PROJECT AND DESCRIPTION PHASE AND PROPOSED MDA PPP MODEL 1 2nd Niger Bridge -Implementation Phase Fed. Min. of Works A Greenfield bridge and associated -Build Operate Transfer approach access road over the River Niger connecting Asaba and Onitsha. 2 Rehabilitation and Upgrade of the -Procurement Phase: Fed. Min. of Works Murtala Mohammed International Selection of preferred Airport (MMIA) Road to Apakun bidder concluded Junction, Lagos - Build Operate Expansion of MMIA access road from Transfer basis a 4-lane dual carriageway to an 8- lane road with vehicular and pedestrian bridges at appropriate locations 3 Rehabilitation and Upgrade of Lagos – -Development Phase: Fed. Min. of Works Iseyin – Kishi – Kaiama Road Outline Business Case The Lagos – Iseyin – Kishi – Kaiama Preparation. Road, Lot IA – will provide direct - Build Operate connectivity between Lagos and the Transfer basis North-West Zone. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria

National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA National lmplementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPS) Final Report Federal Ministry of Environment Abuja, Nigeria April, 2009 Page i National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention FOREWORD The strategic importance of chemicals in the transformation of the economic, industrial, health, social and developmental landscape of Nigeria has been recognized nationally, fully conscious of the risk to human health and the environment by the adoption of unsound management principles and practices especially for hazardous chemicals. Chemicals are important to mankind and sustenance of life on earth with multifarious uses in agriculture, medicine, industrial manufacturing, public health/vector control, etc, yet hazardous chemicals can result in significant adverse effects on human health and the environment. Nigeria as a rapidly industrializing developing country with abundant natural resources, a large human population of about 150 million people and diverse sensitive ecosystems that must be managed in a sustainable manner, has put in place since 1988 institutional and regulatory framework for environmental protection and natural resources conservation. The country has participated actively in most international forum and initiatives on the environment since the 1992 United Nations Conference on the Environment (UNCED); and has ratified major Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) including those on chemicals -

List of Coded Health Facilities in Niger State.Pdf

NIGER STATE HEALTH FACILITY LISTING LGA WARD NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE OWNERSHIP (PUBLIC/ PRIVATE) CODE LGA LGA STATE OWNERSHIP FACILITY NO FACILITY TYPE RURAL HOSP. SECONDARY PUBLIC 26 01 2 1 0001 MCH/FP EKOSSA PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0002 MAYAKI H/CLINIC PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0003 CHATA H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0004 TSADUKO H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0005 EKOSA AGAIE TOWN H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0006 PHCC AGAIE PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0007 PHCC AGAIE PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0008 PHCC AGAIE PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0009 PHCC FOGBE PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0010 PPCC EGBAGI PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0011 PHCC ZAGO PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0012 EKOWUGI PHCC BAWALAGI PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0013 EKOWUGI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0014 MCH/FP/EKOWUNA PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0015 SALAWU H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0016 ESSANGI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0017 EKOWUNA SANTALI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0018 EKPAGI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0019 NDAIJI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0020 TSWACHIKO H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0021 ETSUGAIE B. H/C ETSUGAIE PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0022 LIMAN H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0023 PHCC UMARU PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0024 EWUGI PHCC SHIPO PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0025 MDG ESSUN PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0026 PHCC KIBBAN PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0027 BHC KUTIRIKO PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0028 BOROROKO H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0029 EDOKO H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0030 MASHINA H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0031 EWUGI ESOZHI H/C PRIMARY PUBLIC 26 01 1 1 0032 SEKIWA